I appeared on CBS News Bay Area last week talking about what the Trump administration might do to try to gut California’s electric vehicle requirements:

And a similar story on Monday from CBS News Sacramento:

Yesterday I appeared on two radio shows, now available for streaming or podcast download. First, on KQED Forum, I was on a panel discussing what climate efforts may look like during a Trump Administration, and how California will respond. Joining me was:

- Lisa Friedman, reporter on the climate desk, New York Times

- Jesse Jenkins, assistant professor, engineering, Princeton University

- Aru Shiney-Ajay, Executive Director, Sunrise movement, a grassroots organization of students and young people focused on climate change

You can stream it here.

Then last night I hosted State of the Bay on KALW, where I spoke to UC Berkeley Professor of Chemistry Omar Yaghi about a newly developed carbon-capturing material that has the potential to transform how we address climate change.

Then, we broke down local election results and discussed what they tell us about the priorities and concerns of Bay Area residents with San Francisco Chronicle opinion columnist and editorial writer, Emily Hoeven.

And finally, we talked with Rae Black of Oakland’s For the Win Boxing, a boxing gym that offers professional coaching for women and non-binary people who want to pursue “the sweet science” of boxing.

You can listen to that show here.

On January 27, 2017, just one week after Trump’s inauguration, UC Berkeley Law’s Henderson Center for Social Justice held a daylong “Counter Inauguration,” featuring various panels in reaction to Trump’s victory. I spoke on an afternoon panel that day entitled “Monitoring the Environmental, Social and Governance Impacts of Business in the Trump Era” and offered my predictions on what the Trump years would bring for environmental law and policy.

I recently reviewed these predictions, three months out from the upcoming November election, to see how they measured up against the reality of Trump’s near-complete term in office. Bottom line: these predictions mostly tracked with what happened with Trump and his administration’s leaders, albeit with some steps I missed, some that never came to pass, and some positive outcomes for environmental protection.

First, I predicted the Trump Administration would follow through on the campaign pledges to boost fossil fuels in the following ways:

- Opening up public lands for more oil and gas extraction

- Slashing regulations that limit extraction and related pollution, such as the Clean Power Plan and methane rules

- Weakening fuel economy rules for passenger vehicles

- Financing more infrastructure that could boost automobile reliance (i.e. more highways and less transit)

These were all relatively predictable actions, and they all pretty much happened as predicted. On public lands and fossil fuels, Trump rolled back National Monument protection at Utah’s Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante, as well as streamlined permitting for oil and gas projects on public lands. On environmental rules in general, here is a list of 100 environmental regulations that the administration has tried to reverse. On vehicle fuel economy standards, here’s my article on EPA’s proposed rollback. And transit funding went from 70 percent of transportation grants under Obama to 30 percent under Trump, with the rest funding highways.

Second, I predicted that his administration would try to undermine clean technologies by:

- Weakening tax credits for renewables and electric vehicles

- Undoing federal renewable fuels program

- Revoking California’s ability to regulate tailpipe emissions

- Attempting to undermine California’s sovereignty to regulate greenhouse gases through legislation

- Cutting funding for high speed rail and urban transit

- Withdrawing from Paris agreement

On these predictions, I was correct on most accounts. The administration did weaken tax credits for renewables (both by not extending them or preventing them from decreasing over time, save for a recent one-year extension on wind energy as a budget compromise) and electric vehicles (by letting them expire and threatening to veto Democratic legislation that would have extended them in a recent budget bill). His EPA did revoke California’s waiver to issue tailpipe emission standards. And he famously withdrew from the Paris agreement (to take actual effect later this year) and has tried to cancel almost $1 billion in high speed rail funding in California.

But I was incorrect that the administration would pursue legislation to preempt California’s (and other states’) sovereignty to set their own climate change targets. There was little appetite in Congress to do so, though Trump’s Justice Department did seek unsuccessfully to declare California’s cap-and-trade deal with Quebec to be unconstitutional. And his record on renewable fuels is more mixed but did deliver some gains to corn-based ethanol producers, though the environmental benefits are suspect with this type of biofuel. I also failed to predict the administration’s efforts to impose tariffs on foreign solar PV panels and wind turbines, which slowed those industries somewhat.

Finally, I predicted some possible bright spots for the environment in the Trump years, much of which did occur:

- Clean tech generally has bipartisan support in congress

- Infrastructure spending in general could be negotiated to benefit non-automobile investments

- Lawyers can stop or delay a lot of administrative action on regulations

- A shift will happen now to state and subnational action on climate, which probably needed to happen anyway

Sure enough, clean technology, particularly solar PV, wind and batteries, has continued to increase in the Trump years, though not at the same pace as under Obama due to the policy headwinds. But infrastructure spending has definitely favored automobile interests, as noted above.

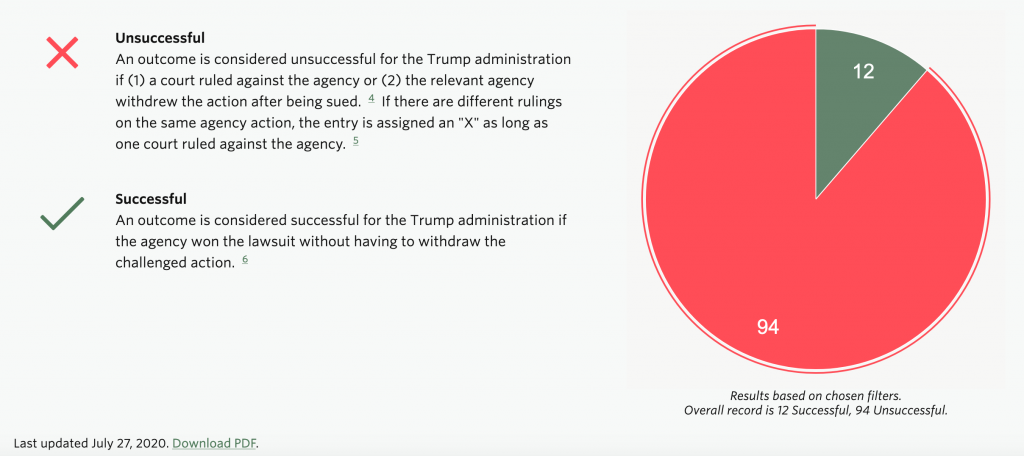

But more importantly, two critical predictions did come to pass. First, attorneys have successfully stopped most administrative rollbacks. In fact, the administration has an abysmal record defending its regulatory actions in court. As NYU Law’s Institute of Policy Integrity has documented, the administration has lost 94 cases in court and won only 12 to date, as tracked in this chart:

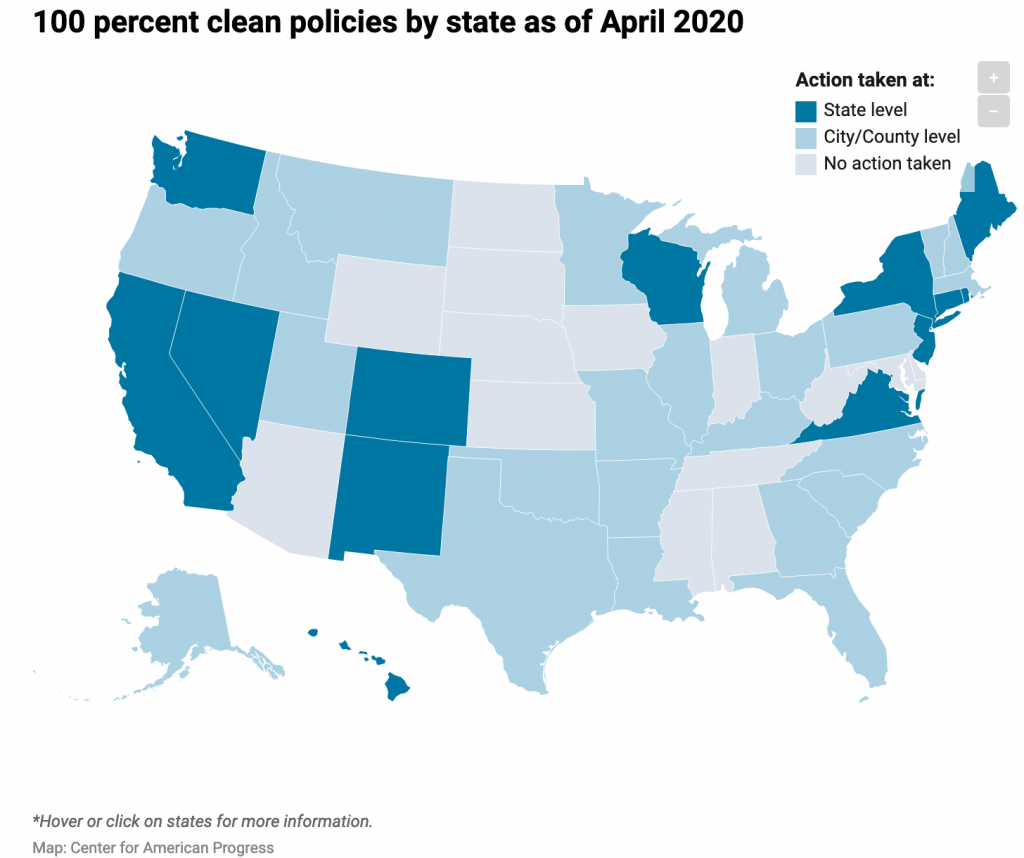

And perhaps more importantly, the lack of federal climate action has moved the spotlight to state and local governments, which often have significant sovereignty to enact aggressive policies that add up to serious national climate action. Take renewable energy, for example, per the Center for American Progress, with this map of states and municipal governments that have enacted 100% clean electricity standards:

And on clean vehicle standards, 13 states plus the District of Columbia now follow California’s aggressive zero-emission vehicle standards, representing about 30 percent of the nation’s auto market.

As a result, in many ways, environmental law and climate action appears to have survived the Trump term in office mostly intact, despite losing progress and facing some setbacks on key issues. Most of the regulatory actions can be reversed by a new administration, while Congressional action during the Trump years was relatively minimal in scope. Meanwhile, the counter-reaction to Trump spurred some significant policy wins at the state and local level.

But while one term is perhaps survivable for environmental law and climate progress, a second one could paint a completely different picture. So the stakes certainly remain high this November.

As part of Trump’s effort to restore U.S. manufacturing (and probably undercut clean energy rivals to his fossil fuel supporters), he instituted in January 30% tariffs on imported solar photovoltaic modules and cells, declining 5% per year to 15% in 2022.

As part of Trump’s effort to restore U.S. manufacturing (and probably undercut clean energy rivals to his fossil fuel supporters), he instituted in January 30% tariffs on imported solar photovoltaic modules and cells, declining 5% per year to 15% in 2022.

At the time, the solar manufacturing industry cried doom-and-gloom about supposedly massive job layoffs and lost solar panel deployment. For example, Solar Energy Industries Association president Abigail Hopper claimed the tariffs would lead to a “crisis” for the industry and potentially cost 260,000 American jobs.

But so far the evidence is underwhelming about the impacts to the industry. As Utility Dive reported:

But while the tariffs are having some negative impacts, the industry and its customers now say their concerns were exaggerated. This is largely because solar installed costs have fallen so far and so fast, especially for utility-scale solar, that the relatively small increase in the module price due to the tariffs is having less of an impact than anticipated.

The examples of specific companies are particularly illuminating:

Recurrent Energy, a leading utility-scale solar developer which opposed the tariffs, has reported no project changes. First Solar, an equally important utility-scale scale developer which endorsed the tariffs, has also announced no major changes.

National residential installer Sunnova and California residential installer Spice Solar both told Utility Dive the falling installed cost has offset the tariffs.

Meanwhile, solar installers are working on legislation to repeal the tariffs, introduced recently by Rep. Jacky Rosen (D-NV).

Tariffs on solar certainly aren’t helpful to the industry. But the reaction so far in the first and most severe year of the tariffs is certainly encouraging. Based on what we’ve seen, it sounds like even Trump’s hostility to clean energy isn’t enough to slow the pace of deployment.

Will this place still be “Carrizo Plain National Monument” after Trump’s administration has its way? Photo by Steve Hymon

In these first 100 days, our new president has backtracked on many promises, completely reversed course in others, and demonstrated an alarming disregard for the truth.

It’s enough to make some political observers think that he’s basically a malleable mishmash of blathering, with his only core desire to self-promote and perhaps increase his riches from from his various business dealings.

As Andrew Sullivan wrote recently:

What on earth is the point of trying to understand him when there is nothing to understand? Calling him a liar is true enough, but liars have some cognitive grip on reality, and he doesn’t. Liars remember what they have said before. His brain is a neural Etch A Sketch. He doesn’t speak, we realize; he emits random noises. He refuses to take responsibility for anything. He can accuse his predecessor and Obama’s national security adviser of crimes, and provide no evidence for either. He has no strategy beyond the next 24 hours, no guiding philosophy, no politics, no consistency at all — just whatever makes him feel good about himself this second. He therefore believes whatever bizarre nonfact he can instantly cook up in his addled head, or whatever the last person who spoke to him said. He makes Chauncey Gardiner look like Abraham Lincoln. Occam’s razor points us to the obvious: He has absolutely no idea what he’s doing. Which is reassuring and still terrifying all at once.

That may be true when it comes to Trump personally and as a politician. But it does not apply when it comes to his appointees in the administration on the environment. Because across-the-board, the administration seems motivated by one thing when it comes to the environment, and that’s boosting the oil, gas, and coal industries at the expense of everything else.

There are too many examples to cite, but it’s worth going through some of them:

- Attempting to roll back key regulations like the Clean Power Plan and the fuel economy standards

- Gutting the budget for the Environmental Protection Agency, Department of Energy clean tech research, and public transit, among others

- Overturning environmental regulations with Congress through use of the once-obscure Congressional Review Act

- Reviewing, with the likely intent of undoing, prior national monument designations, including the Carrizo Plain here in California that I recently profiled.

So while Trump may be incoherent and bereft of some core principles, he has empowered an administration full of individuals dead set on boosting oil, gas, and coal exploitation, at the expense of the environment and public health.

Yesterday was a frustrating day for those who care about tackling climate change. Donald Trump’s executive order to roll back most of the Obama Administration’s efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions is probably a futile attempt to resuscitate the dying coal industry, while putting America’s climate leadership on ice for at least the next four years. In other words, it’s a pointless, counter-productive exercise.

Yet while the moves are disappointing, they’re not devastating. The executive order will set in motion a regulatory process that will take years to play out and that will likely face strong resistance from the courts. But they mean a giant delay in needed actions.

I commented on the moves yesterday in some media outlets in both Los Angeles and the San Francisco Bay Area. First, I appeared on KPCC radio’s AirTalk in Los Angeles, discussing the impact of the order.

In the afternoon, I spoke with ABC-7 News in the Bay Area. Video here:

So the action now will shift to the courts, and we’ll see what the administration does with the Paris agreement on climate change going forward.

The New York Times offers a good rundown of the various environmental laws and regulations that Trump’s administration will likely attempt to roll back. The upside: many of these agency actions could take years to unwind, likely leaving the final call for efforts like the Clean Power Plan in the hands of the 2020 presidential election winner.

The downside: a number of executive orders, such as preventing coal mining on public lands, can be undone right away. Other rules, like the methane limits on oil extraction, can also be undone by Congress through the Congressional Review Act. And perhaps most significantly, the Trump administration can try to weaken fuel economy standards for automakers, although that too will take time and litigation.

Of course, if Congress can act to weaken the Clean Air Act and other environmental laws, all bets are off. But as long as the filibuster remains in the Senate, that may be hard to do.

Meanwhile, there may be some glimmer of hope on clean technology with the new administration. Trump’s nominee for Treasury secretary backed the production tax credit for wind power (the solar tax credit’s fate may be less certain, and both tax credits could be undermined by broader corporate tax reductions, but still). Tesla/SolarCity CEO Elon Musk also apparently has the ear of Trump on EV manufacturing, which can’t hurt. And while it’s been only a week since the inauguration, Trump hasn’t yet withdrawn the U.S. from the landmark Paris agreement on climate change, while Exxon, incoming Secretary of State Tillerson’s former company, just praised the agreement.

There is still little reason for environmentalists to get their hopes up, and the idea of actually proactively tackling our environmental challenges at the federal level is all but dead for the next four years. But the current legal environment on the environment may be a bit more stable than we might otherwise assume.

It’s the big guessing game, given that the federal investment and production tax credits have been a major stimulant for renewables deployment in the U.S. President-elect Trump is famously pro-fossil fuels, but some renewables advocates hope that the industry’s bipartisan support, declining costs, and record of domestic jobs production will help it weather the Trump storm.

It’s the big guessing game, given that the federal investment and production tax credits have been a major stimulant for renewables deployment in the U.S. President-elect Trump is famously pro-fossil fuels, but some renewables advocates hope that the industry’s bipartisan support, declining costs, and record of domestic jobs production will help it weather the Trump storm.

Two big titans of the field, Bill Gates and Elon Musk, have differing views of what will happen, based on their conversations with the president-elect. First per PV Tech, Gates is pessimistic:

After a call on clean energy with Donald Trump, Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates fears for federal support of renewables under the new US president. […]

Gates announced the formation of the Breakthrough Energy Coalition, the group that is launching the fund, at COP21 last year. In addition to the private investments, Gates said he and other investors convinced 20 governments to double their energy research and development budgets over the next five years.

In light of the call with Trump, however, Gates doubts how involved the US government will be in that commitment.

Gates acknowledged that the US “will probably see at the federal level less incentives for renewable deployment” during the Trump administration. “That is unfortunate,” he said.

But Musk is sounding more optimistic after meeting with Trump, per Eletrek:

During an event with investors at the Gigafactory in Nevada this week, Musk described his takeaway from the meeting and it looks somewhat encouraging for the clean tech industry.

Investors attending the event told Electrek that Musk said the following when his meeting with Trump came up:

“The President-elect has a strong emphasis on US manufacturing and so do we. We are building the biggest factory in the world right here, creating US jobs… I think we may see some surprising things from the next administration. We don’t think they will be negative on fossil fuels… but they may also be positive on renewables.”

For my part, I could envision two possible futures for renewable incentives, both of which are not great. First, Congress could eliminate the tax incentives in a larger budget deal that cuts taxes significantly, since they’ll need to find offsetting revenue any way they can. The tax credits could therefore be among the first to give.

Alternatively, Congress might keep the tax incentives as is but cut corporate tax rates so much that they become ineffective. Boomberg described how this would work back in November:

Wind and solar companies depend heavily on financing from large banks, insurers and other backers that take advantage of federal credits through tax-equity financing — they’re expected to provide developers with about $14.8 billion this year, according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance.

If corporate rates fall, as Trump has pledged if he is elected Tuesday, investors will have less need for write-offs through tax-equity investments. With wind and solar projects expected to need $56.2 billion in capital during the next president’s first term, a slump in the tax-equity market may leave developers short.

If corporations owe less to the government, “there will be less tax capacity to be taken up with tax equity,” said Keith Martin, a Washington-based attorney for law firm Chadbourne & Parke LLP who specializes in tax and project finance.

I hope I’m proven wrong and that the incentives stay strong, but it’s probably worth gearing up for at least some degree of rollback. And that means strong advocacy in Congress to keep the incentives effective, and also coordinated state action among pro-renewable states to provide financing backstops in case of federal retrenchment.

The Associated Press reports that it may be one more campaign promise that goes down with the reality of Republican control of Congress:

The Associated Press reports that it may be one more campaign promise that goes down with the reality of Republican control of Congress:

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell tried to tamp down expectations last week, telling reporters he wants to avoid “a $1 trillion stimulus.” And Reince Priebus, who will be Trump’s chief of staff, said in a radio interview that the new administration will focus in its first nine months with other issues like health care and rewriting tax laws. He sidestepped questions about the infrastructure plan.

In a post-election interview with The New York Times, Trump himself seemed to back away, saying infrastructure won’t be a “core” part of the first few years of his administration. But he said there will still be “a very large-scale infrastructure bill.”

He acknowledged that he didn’t realize during the campaign that New Deal-style proposals to put people to work building infrastructure might conflict with his party’s small-government philosophy.

“That’s not a very Republican thing – I didn’t even know that, frankly,” he said.

It shouldn’t be a shock, given Republican resistance to Obama’s infrastructure proposals. But at the same time, I wouldn’t be surprised if Republicans in Congress cave to Trump on this one eventually, particularly if the economy goes south. They’ll need the economic boost heading into the 2018 midterms, and Republican fealty to fiscal conservatism tends to go out the window once a member of their own party is in the White House (see Bush, George W.).

Still, it’s too bad if the program doesn’t happen, as low interest rates and a huge backlog of transportation needs across the country would make this a prime time to spend money on rebuilding and repairing our infrastructure.

The consequences of the presidential election on national policy are becoming clearer each day, as Trump appoints deeply anti-government people to run major agencies, from education to labor to the EPA. Progressive groups will likely be on defense for the next four or more years, putting our country’s ability to remain an international leader on issues like the environment in jeopardy.

The consequences of the presidential election on national policy are becoming clearer each day, as Trump appoints deeply anti-government people to run major agencies, from education to labor to the EPA. Progressive groups will likely be on defense for the next four or more years, putting our country’s ability to remain an international leader on issues like the environment in jeopardy.

With that in mind, it’s worth looking back at the campaign that put the country in this situation. Politico has a fascinating piece on the 10 big decision points that shaped the race, culled from interviews with key players over the 18-month campaign. The points range Clinton and Trump’s decisions to run, to some of the big moments, like Sanders not attacking Clinton on emails and the FBI director’s last-minute letter on Clinton’s emails.

It’s a long piece, but here is probably the key passage:

But, in the end, Brooklyn [Clinton campaign headquarters] simply failed to predict the tidal wave that swamped Clinton—a pro-Trump uprising in rural and exurban white America that wasn’t reflected in the polls—and his candidate failed to generate enough enthusiasm to compensate with big turnouts in Detroit, Milwaukee and the Philadelphia suburbs.

Either way, there was something missing that technocrats couldn’t fix: The candidate herself was deeply unappealing to the most fired-up, unpredictable and angry segment of the electorate—middle-income whites in the Middle West—and she couldn’t inspire Obama-like passion among her own supporters to compensate for the surge.

The piece also goes through Trump’s relationship with the media and how he honed his strategy, with rallies that allowed him to test his messaging and develop material like a stand-up comedian on the road.

I was particularly struck at how a demagogue-style, populist message of darkness resonated in this country, even in his post-convention attack on a Gold Star family (the Khans):

“If he loses,” Robby Mook, Clinton’s campaign manager, told me at the time, “his attack on Khans was the turning point.”

But here’s the thing: At that very moment, Mook’s own internal data was showing that Trump’s negative message overall—his “diagnosis of the problem” as Brooklyn called it—was resonating.

Clinton’s team laughed off Trump’s nomination speech. Yet her pollster John Anzalone and his team were stunned to find out that dial groups of swing state voters monitored during the speech “spiked” the darker the GOP nominee got, according to a staffer privy to the data.

The article also criticizes Clinton’s decision to essentially take time off in August and let Trump come back, as well as her decision not to campaign more in the rust belt, which was always touted as Trump’s only path to victory:

Jake Sullivan, Clinton’s policy director—a brainy and nervous former State Department aide who took on an increasingly important political role as the campaign ground on—was the only one in Clinton’s inner circle who kept saying she would likely lose, despite the sanguine polling, according to his friends. He was also the only one of the dozen aides who dialed in for Clinton’s daily scheduling call who kept on asking if it wasn’t a good idea for her to spend more time in the Midwestern swing states in the closing days of the campaign.

His suggestion wasn’t rejected; it never got that far because nobody else on the call thought it was a good idea. They spent far more time debating whether or not Clinton should visit Texas and Arizona, two states they knew she had little chance of winning, in order to get good press.

There are other good post-mortems on the election out there, particularly David Roberts’ recent piece at Vox, and political junkies could spend hours reading and debating.

But as the analysis settles, we’ll have to address the consequences of this election on national policy. And given the direction so far (to say nothing of the campaign trail rhetoric), they’re likely to be massive.