When did America go from “These United States of America” to “The United States” (i.e. singular)? When did citizens in this country stop identifying primarily with their state (be it Massachusetts, South Carolina, or Virginia) and instead call themselves first and foremost “Americans”?

While we celebrate our country’s birthday tomorrow, many of us are unaware of how the U.S. Constitution — and our culture around the role of the federal government — has changed since the founding. Many of those changes are due to the Civil War and President Lincoln.

Berkeley Law’s constitutional law expert (and my colleague and faculty director) Dan Farber discusses these changes on the Weekly Constitutional podcast, “Abe Lincoln’s Constitution”:

Worth reflecting on this subject as we celebrate the 4th during turbulent political times.

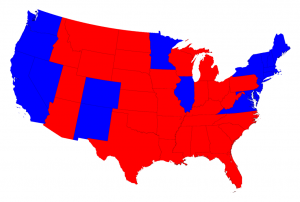

Richard Florida argues in Politico.com that the election of Trump should bolster calls to devolve more power to states and specifically cities. While he acknowledges that some of this smacks of “sore loser” federalism, it would address a growing structural problem in governing a nation as large and diverse as the U.S.:

Richard Florida argues in Politico.com that the election of Trump should bolster calls to devolve more power to states and specifically cities. While he acknowledges that some of this smacks of “sore loser” federalism, it would address a growing structural problem in governing a nation as large and diverse as the U.S.:

Even on the domestic level, though, the modern-day presidency is crazy when you think about it: Why would a nation of 300 million-plus people, 50 states, 350-plus metro areas, 3,000-plus counties, and thousands and thousands of cities and communities choose to vest so much power in one person and one office? If there were any doubt about it before, we now know for a certainty that our current governance system, with its packing of humongous power in a unitary executive, is vulnerable to catastrophic failure. In addition to our well-understood horizontal separation of powers among the executive, legislative and judicial branches of government, the vertical separation of powers among the federal government, the states and the local level provides a further set of safeguards and protections that we can and must use better. As a number of large corporations have discovered, devolving decision-making from executive suites to work groups on the factory floor drives huge productivity gains.

I’m sympathetic with much of the progressive policy aims for the federal government over the last century or so, from basic social safety nets to labor and environmental standards to civil/women’s rights and infrastructure investment. But Florida’s point is hard to argue with. In a country as large and diverse as ours, with so much power now concentrated in the federal government, each election becomes a divisive tug-of-war now prone, as Florida says, to democratic (small “d”) catastrophe.

Some of this “devolution revolution” could be straightforward, such as allowing states more flexibility on infrastructure investment. As a pro-transit person, the federal government hasn’t been great on this issue anyway, mostly funding highways, and in recent years, not funding much of anything.

But Florida doesn’t grapple with some of the hard choices and trade-offs this approach would entail. Are we comfortable as a nation allowing some states to continue discriminating against women, minorities and religious groups? To pollute their environment, when the effects might spill over to neighboring states? To weaken labor and safety standards? And of course to roll back social safety nets like Medicare and Social Security?

The upside, perhaps, is that states would be freer to solve these problems themselves, and we’d get a true laboratory effect going. People would be free to move to more successful and tolerant states, as the Great Migration exemplified. We’d also potentially ratchet down the growing tension in this country between affluent, urban areas and economically stagnant and declining rural regions.

But it would come at a cost to specific policies and policy goals that need to be addressed head on.

It’s worth considering as a long-term response to a problem that is much bigger than just one presidential election, and that won’t be resolved with just a change in leadership.