It’s fine if you don’t like Elon Musk. But it’s a mistake to let antipathy for Musk’s ideas, businesses and public persona color your view of electric vehicles, and more specifically Tesla.

And that’s exactly what happens to token “conservative” New York Times opinion writer Bret Stephens. Stephens is otherwise known (at least to me) as a climate skeptic. But in a scathing and highly personal attack on Elon Musk, he betrays ignorance of another subject: electric vehicles.

After comparing Musk to Trump, he makes some misleading charges about Tesla:

Strong words — too strong, if you ask the satisfied customers of Tesla’s Model S (base price, $74,500) and X ($79,500). But Tesla is supposed to be the auto manufacturer of the future, not a bauble maker for the rich.

The company has rarely turned a profit in its nearly 15-year existence. Senior executives are fleeing like it’s an exploding Pinto, and the company is in an ugly fight with the National Transportation Safety Board. It burns through cash at a rate of $7,430 a minute, according to Bloomberg. It has failed to meet production targets for its $35,000 Model 3, for which more than 400,000 people have already put down $1,000 deposits, and on which the company’s fortunes largely rest.

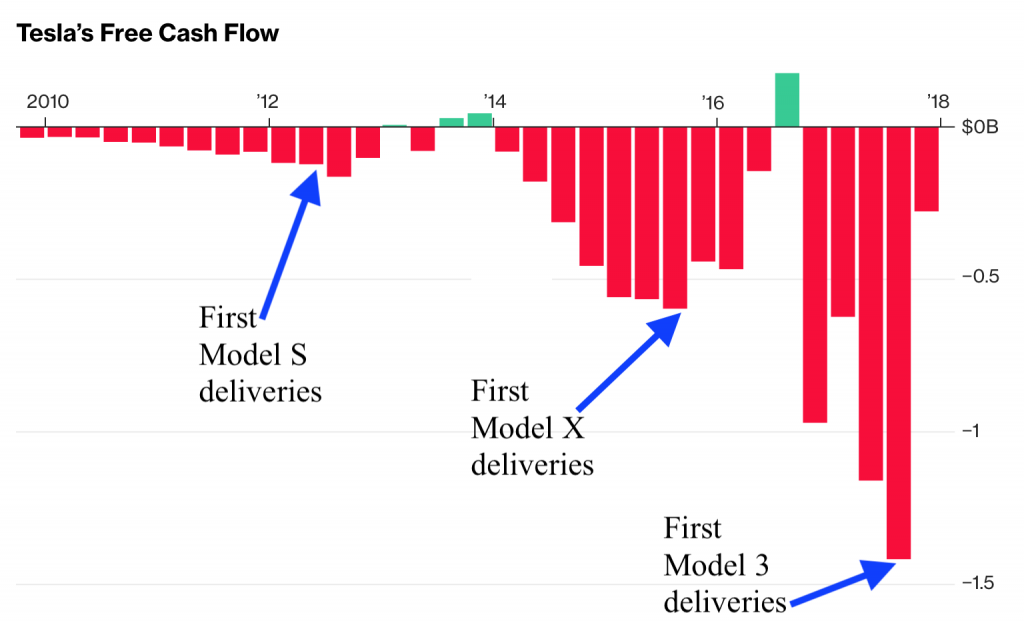

Stephens makes Tesla sound like a money-losing luxury automaker. But Tesla could have easily turned a profit a long time ago, if it was in the short-term profit game. But it’s burning cash precisely because it’s scaling up a massive battery, solar panel and mass-market vehicle business. Check out this chart on Tesla cash flow from Ars Technica:

It’s silly for Stephens to take a snapshot of Tesla’s current losses without broader context and insight into the company’s business plan. He whiffs on this score.

It’s silly for Stephens to take a snapshot of Tesla’s current losses without broader context and insight into the company’s business plan. He whiffs on this score.

But it gets worse. He then lobs a broad attack against EVs in general:

Tesla, by contrast, today is a terrible idea with a brilliant leader. The terrible idea is that electric cars are the wave of the future, at least for the mass market. Gasoline has advantages in energy density, cost, infrastructure and transportability that electricity doesn’t and won’t for decades. The brilliance is Musk’s Trump-like ability to get people to believe in him and his preposterous promises. Tesla without Musk would be Oz without the Wizard.

Much of the blame for the Tesla fiasco goes to government, which, in the name of green virtue, decided to subsidize the hobbies of millionaires to the tune of a $7,500 federal tax credit per car sold, along with additional state-based rebates. Would Tesla be a viable company without the subsidies? Doubtful. When Hong Kong got rid of subsidies last year, Tesla sales fell from 2,939 — to zero. It may be unfair to describe Tesla as Solyndra on wheels, but only slightly.

It’s time for fact checks. First, lithium ion batteries and electricity rival gasoline in all categories Stephens mentions. Electricity is ubiquitous (and locally produced). Batteries can recharge in minutes with technology now being introduced on the market, just like a gas station. And cheaper battery packs deliver the range today of a full tank of gas. And on all these fronts, the technology and infrastructure is set to improve in the next few years — not decades, as Stephens suggests.

But even more important, electricity as a fuel doesn’t poison our air and lungs like burning gasoline — or leave us dependent on foreign governments for a global commodity. Gasoline is not priced for those externalities. Since Stephens doesn’t accept climate science, he may not care. But the rest of us should.

And this notion that Tesla survives on government handouts is also misleading. Many Tesla customers are wealthy enough where the tax incentives and rebates don’t factor into their decision-making, according to data collected in California on rebate customers. If anything, Tesla is now hurt by government incentives for fossil fuels and rival automakers with new electric vehicles on the market.

In short, Stephens is ignorant on this topic and unfortunately has written a column that spreads misinformation on a critical climate-fighting technology.

Bret Stephens, the New York Times’ new columnist, got the climate change world into an outrage with his first column last week, which compared climate science to Hillary Clinton’s pre-election polling and argued for restraint from climate advocates.

In his follow up column today, he took a more measured tone, noting that he believes the Earth is warming but that we’re not being careful on the solutions:

“The British government provided financial incentives to encourage a shift to diesel engines because laboratory tests suggested that would cut harmful emissions and combat climate change. Yet, it turned out that diesel cars emit on average five times as much emissions in real-world driving conditions as in the tests, according to a British Department for Transport study.”

In other words, to say we want to take out insurance for climate change is perfectly sensible. But whether we know we’re buying the right insurance, at the right price, is less clear, and it behooves us to look closely at the fine print before we sign on.

As someone who works day in and day out on climate mitigation policies, I can tell you that Stephens is cherry-picking from a handful of bad examples.

Take his reference to the ethanol subsidies, which resulted from the federal renewable fuel standard, established during the second Bush administration. Yes, the standard did spur more Midwestern corn production to be used for biofuel.

But the policy was never really a climate mitigation measure. It was primarily meant to boost domestic fuel sources, with greenhouse gas reduction as an added selling point but no strict carbon screen on the fuels. If there was a strong carbon screen on the kind of fuel that could qualify, very little of that high-carbon Midwestern corn-based ethanol would have qualified (hence the opposition to the standard even from some environmentalists).

For a better climate policy model on biofuels, just look to California. The state’s low carbon fuel standard (which encourages biofuel production like the renewable fuel standard but with a strong low-carbon requirement) disfavors land-intensive corn for true low-carbon biofuel, like in-state used cooking oil (surprisingly a growing percentage of the state’s biofuel).

Stephens’ reference to the British diesel problem is also unfortunate. Most climate policy experts will tell you that the best way to reduce emissions from transportation is through battery electric vehicles, as long as the electricity doesn’t come exclusively from coal-fired power plants (in which case hybrid vehicles yield better carbon reductions). Other fuels that can work include low-carbon biofuels and possibly hydrogen, depending on the energy source used to produce it. Diesel isn’t on the list, at least in places like California, unless it’s biodiesel.

On that subject, biodiesel does emit conventional pollutants, an issue we’re grappling with in California, as evidenced by the POET lawsuit against the California Air Resources Board’s low carbon fuel standard. Biodiesel is great at reducing carbon emissions but also emits nitrogen oxide (NOx) — a subject we covered in Berkeley/UCLA Law’s 2015 Planting Fuels report.

On that subject, biodiesel does emit conventional pollutants, an issue we’re grappling with in California, as evidenced by the POET lawsuit against the California Air Resources Board’s low carbon fuel standard. Biodiesel is great at reducing carbon emissions but also emits nitrogen oxide (NOx) — a subject we covered in Berkeley/UCLA Law’s 2015 Planting Fuels report.

Resolving this conflict among pollutants will take a policy balancing act, but it ultimately shouldn’t obscure the huge economic and environmental benefits from switching transportation fuels from petroleum to electricity and low-carbon biofuels. Stephens simply ignores this tried-and-true approach, which is resulting in swift advancements in electric vehicle adoption in places like California, Europe, and even China.

To be sure, care is needed when it comes to developing climate policies, and I’d agree with Stephens on that front. But the main concern is around managing the economic impacts of transitioning the grid and transportation fuels to cleaner sources. We have to go slow to avoid price shocks and bring the costs of these new technologies down.

California is doing just that, with a measured, careful plan to bring down the emissions curve steeply over the coming decades. Our economy is now less carbon intensive than it was in the 1990s and has been growing rapidly, too — which is at least an indication that climate policies aren’t getting in the way, if not actually serving as a boost.

There’s no reason that the country as a whole can’t follow suit, except that we have national writers like Stephens who cherrypick their way into sounding like reasonable skeptics — when they’re really just misleading people.