Your high carb diet may be helping California achieve a low-carbon future. The state’s aggressive low-carbon fuels mandates have increasingly encouraged large-scale fuel consumers to purchase biofuels from restaurant “brown grease” in order to meet the requirements.

Your high carb diet may be helping California achieve a low-carbon future. The state’s aggressive low-carbon fuels mandates have increasingly encouraged large-scale fuel consumers to purchase biofuels from restaurant “brown grease” in order to meet the requirements.

This renewable diesel from plants and animal fat can be used without blending because of its similar properties to petroleum diesel (see our Planting Fuels report for more information). Biodiesel, on the other hand, is more limited, as it typically maxes out at 20 percent as a blended fuel with petroleum, due to automaker restrictions.

While the state aims for a future of battery-powered vehicles to reduce transportation emissions, biofuels like renewable diesel are currently picking up most of the slack. As Robert Tuttle in Bloomberg describes:

In recent years, cities such as San Francisco, Oakland, and San Diego, as well as Sacramento County, have transitioned to using renewable diesel to power buses, fire engines and other city vehicles. Alphabet Inc.’s shuttle buses in Silicon Valley also burn it, and UPS said two years ago that it would buy 46 million gallons of the fuel to run its fleet of delivery trucks.

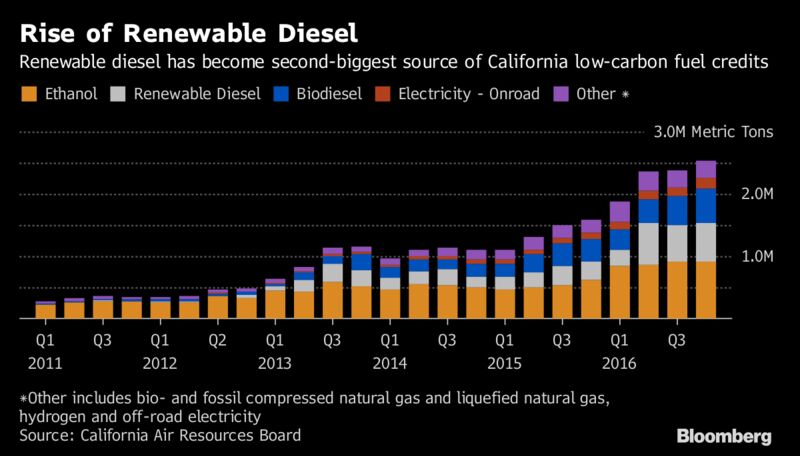

As the article shows in the chart below, the result of this readily available, if not unhealthy, feedstock is a growing percentage of brown grease-based renewable diesel offsetting petroleum fuel usage:

Of course, meat-heavy diets are making climate change worse. But at least in the short run, this is one fat solution to the problem.

Bret Stephens, the New York Times’ new columnist, got the climate change world into an outrage with his first column last week, which compared climate science to Hillary Clinton’s pre-election polling and argued for restraint from climate advocates.

In his follow up column today, he took a more measured tone, noting that he believes the Earth is warming but that we’re not being careful on the solutions:

“The British government provided financial incentives to encourage a shift to diesel engines because laboratory tests suggested that would cut harmful emissions and combat climate change. Yet, it turned out that diesel cars emit on average five times as much emissions in real-world driving conditions as in the tests, according to a British Department for Transport study.”

In other words, to say we want to take out insurance for climate change is perfectly sensible. But whether we know we’re buying the right insurance, at the right price, is less clear, and it behooves us to look closely at the fine print before we sign on.

As someone who works day in and day out on climate mitigation policies, I can tell you that Stephens is cherry-picking from a handful of bad examples.

Take his reference to the ethanol subsidies, which resulted from the federal renewable fuel standard, established during the second Bush administration. Yes, the standard did spur more Midwestern corn production to be used for biofuel.

But the policy was never really a climate mitigation measure. It was primarily meant to boost domestic fuel sources, with greenhouse gas reduction as an added selling point but no strict carbon screen on the fuels. If there was a strong carbon screen on the kind of fuel that could qualify, very little of that high-carbon Midwestern corn-based ethanol would have qualified (hence the opposition to the standard even from some environmentalists).

For a better climate policy model on biofuels, just look to California. The state’s low carbon fuel standard (which encourages biofuel production like the renewable fuel standard but with a strong low-carbon requirement) disfavors land-intensive corn for true low-carbon biofuel, like in-state used cooking oil (surprisingly a growing percentage of the state’s biofuel).

Stephens’ reference to the British diesel problem is also unfortunate. Most climate policy experts will tell you that the best way to reduce emissions from transportation is through battery electric vehicles, as long as the electricity doesn’t come exclusively from coal-fired power plants (in which case hybrid vehicles yield better carbon reductions). Other fuels that can work include low-carbon biofuels and possibly hydrogen, depending on the energy source used to produce it. Diesel isn’t on the list, at least in places like California, unless it’s biodiesel.

On that subject, biodiesel does emit conventional pollutants, an issue we’re grappling with in California, as evidenced by the POET lawsuit against the California Air Resources Board’s low carbon fuel standard. Biodiesel is great at reducing carbon emissions but also emits nitrogen oxide (NOx) — a subject we covered in Berkeley/UCLA Law’s 2015 Planting Fuels report.

On that subject, biodiesel does emit conventional pollutants, an issue we’re grappling with in California, as evidenced by the POET lawsuit against the California Air Resources Board’s low carbon fuel standard. Biodiesel is great at reducing carbon emissions but also emits nitrogen oxide (NOx) — a subject we covered in Berkeley/UCLA Law’s 2015 Planting Fuels report.

Resolving this conflict among pollutants will take a policy balancing act, but it ultimately shouldn’t obscure the huge economic and environmental benefits from switching transportation fuels from petroleum to electricity and low-carbon biofuels. Stephens simply ignores this tried-and-true approach, which is resulting in swift advancements in electric vehicle adoption in places like California, Europe, and even China.

To be sure, care is needed when it comes to developing climate policies, and I’d agree with Stephens on that front. But the main concern is around managing the economic impacts of transitioning the grid and transportation fuels to cleaner sources. We have to go slow to avoid price shocks and bring the costs of these new technologies down.

California is doing just that, with a measured, careful plan to bring down the emissions curve steeply over the coming decades. Our economy is now less carbon intensive than it was in the 1990s and has been growing rapidly, too — which is at least an indication that climate policies aren’t getting in the way, if not actually serving as a boost.

There’s no reason that the country as a whole can’t follow suit, except that we have national writers like Stephens who cherrypick their way into sounding like reasonable skeptics — when they’re really just misleading people.

As California commits itself to reducing greenhouse gas emissions from the transportation sector, what role will biofuels play as a petroleum alternative? And how can California ensure that more low-carbon biofuels are produced in-state, especially given the competition from cheap oil and cheap international biofuel?

As California commits itself to reducing greenhouse gas emissions from the transportation sector, what role will biofuels play as a petroleum alternative? And how can California ensure that more low-carbon biofuels are produced in-state, especially given the competition from cheap oil and cheap international biofuel?

State officials and biofuel producers will address these questions at a free legislative lunch briefing this Friday, January 22nd, in the Capitol. The event will also discuss findings from the recent UCLA/UC Berkeley Law report on ways to boost in-state biofuel production, “Planting Fuels: How California Can Boost Local, Low-Carbon Biofuel Production.”

The event will include the following speakers:

- Lisa Mortenson, chief executive officer at Community Fuels

- Tim Olson, energy and fuels program manager at the California Energy Commission

- Cliff Rechtschaffen, senior adviser to Governor Brown

- Floyd Vergara, industrial strategies division chief, California Air Resources Board

When: January 22, 2016, 12:00pm-1:30pm

Where: Governor’s Office large conference room, Capitol Building, Sacramento

Lunch will be served. More information can be found here. Please note space is limited, so register soon via this link.

Last month Berkeley and UCLA Law hosted a webinar on our new report “Planting Fuels,” which offers recommendations to boost low-carbon biofuel production in California. These biofuels will be vital to reducing greenhouse gas emissions from the transportation sector in the long-term, particularly for aviation and long-haul trucking. The video is now finally available on-line:

As I blogged earlier this month, UC Berkeley and UCLA Law released a report on how to boost low-carbon biofuels in California. To learn more about the report and its recommendations, please join us for a webinar today from 11am to noon. Speakers will include:

As I blogged earlier this month, UC Berkeley and UCLA Law released a report on how to boost low-carbon biofuels in California. To learn more about the report and its recommendations, please join us for a webinar today from 11am to noon. Speakers will include:

- Tim Olsen, energy and fuels program manager at the California Energy Commission

- Lisa Mortenson, chief executive officer at Community Fuels

- Mary Solecki, western states advocate for Environmental Entrepreneurs

You can register via this site. Hope to “see” you there!

On Sunday the Sacramento Bee published my op-ed on how California can boost in-state production of low-carbon biofuels — not the wasteful Midwestern corn kind of biofuels. Here’s an excerpt:

[T]he state has not yet taken full advantage of the the ndiverse opportunities for low-carbon biofuel production from in-state biomass. While policies such as the state’s recently revised low-carbon fuel standard have put California on a leadership path in incorporating low-carbon biofuels into our transportation fuel mix, more federal and state action could ensure that California maximizes the environmental and economic potential of in-state innovation and production.

Federal and state leaders could:

- Provide greater support for in-state biofuel production, taking into account the full range of local biofuel carbon benefits and co-products, like biochar compost that can sequester carbon, and thin-film plastic to bed strawberries and tomatoes.

- Offer financial incentives for automakers and gas stations to allow and sell greater amounts of low-carbon biofuels and higher blend rates.

- Improve access to and financial support for in-state feedstock production, particularly on idled farmland and forestland to reduce wildfire risks.

Ultimately, California should set a goal of providing at least half of its low-carbon biofuel from in-state sources. Locally produced, low-carbon biofuel is an important bridge fuel to meet the state’s long-term climate goals, and it will benefit California’s environment and economy in the process.

You can read our new UC Berkeley / UCLA report on the subject here.

When we think of ways to reduce emissions from petroleum-based transportation fuels, electric vehicles get much of the headlines. Battery electric transportation certainly offers a viable, long-term alternative to petroleum fuels. But we’re still a few years away from an affordable, mass-market electric vehicle, and battery technology may be decades away, if ever, from being suitable for uses like long-haul trucking and aviation.

When we think of ways to reduce emissions from petroleum-based transportation fuels, electric vehicles get much of the headlines. Battery electric transportation certainly offers a viable, long-term alternative to petroleum fuels. But we’re still a few years away from an affordable, mass-market electric vehicle, and battery technology may be decades away, if ever, from being suitable for uses like long-haul trucking and aviation.

So what do we do in the meantime, if we hope to achieve California’s carbon reduction goals? Transportation, after all, is the single biggest source of greenhouse gas emissions in the state.

The response may in fact be growing all around us. Biofuels from agricultural sources like canola and corn, as well as algae, forest residue, and food waste, among others, can provide a low-carbon alternative to petroleum fuels, depending on its source and type. Certainly not all biofuels are environmentally beneficial, and one of the knocks on the federal Renewable Fuels Standard statute, with just-released new implementing rules from EPA announced on Monday, is that the law promotes biofuels that may actually be worse for the environment than petroleum fuels, given their production pathways and land use impacts.

But here in California, we have the opportunity to meet our climate goals while producing as much as half of our biofuels from low-carbon, in-state sources. To suggest policies that could boost this in-state production, UC Berkeley and UCLA Law are today releasing a new report “Planting Fuels: How California Can Boost Local, Low-Carbon Biofuel Production.” The report is the 16th in the two law schools’ Climate Change and Business Research Initiative, generously supported by Bank of America since 2009.

While California has a small but growing amount of biofuel production and consumption, federal and state leaders could do more to boost low-carbon, innovative biofuels. These leaders could:

- Provide greater support for in-state biofuel production, taking into account the full range of local biofuel carbon benefits and co-products, like biochar compost that can sequester carbon and thin-film plastic to bed strawberries and tomatoes;

- Offer financial incentives for automakers and gas stations to allow and sell greater amounts of low-carbon biofuels and higher blend rates; and

- Improve access to and financial support for in-state feedstock production, particularly on idled farmland and forest lands to reduce wildfire risks.

With these steps, California could power our cars, trucks and airplanes in a more environmentally beneficial manner, while boosting local economies in the process.

To learn more about the report and its recommendations, please join us for a webinar on December 14th from 11am to noon. Speakers will include:

- Tim Olsen, energy and fuels program manager at the California Energy Commission

- Lisa Mortenson, chief executive officer at Community Fuels

- Mary Solecki, western states advocate for Environmental Entrepreneurs

You can register via this site. We hope you can join for further discussion on this important topic.