Rendering of proposed gondola to Dodgers Stadium

Who knew gondolas and baseball games could be a thing? But now we have two major league baseball teams — the Oakland A’s and Los Angeles Dodgers — exploring options to build gondolas to ferry fans from rail transit stations to the park.

As Jenna Chandler at Curbed L.A. reported, the Dodgers are working with a private company to submit plans for an “aerial tram” to link the major transit and train hub of Union Station near Downtown L.A. across the freeway to Dodgers Stadium in Chavez Ravine.

The project is estimated to cost $125 million and would be privately funded, with unclear support required from L.A. Metro to provide procedural assistance and right-of-way selection. The tram could potentially be operational by 2022.

Meanwhile, the Oakland A’s hope a gondola could solve the transportation challenges at one of their best remaining sites for a new ballpark, on the waterfront near Jack London Square. The problem with the site is that — like Dodger Stadium — it’s across the freeway and more than a mile away from the nearest BART station in Downtown Oakland. A BART or streetcar extension is too costly, so the team is also examining the gondola option.

A gondola can be a fun way to get around, and the prospect of an elevated ride over the freeways with nice views of the surrounding California hills and neighborhoods could entice a lot of fans. But gondolas can’t carry a lot of people. For example, the Dodgers gondola would only move 5,000 people an hour, while the A’s one has been estimated at 8,000 an hour at the most. That’s pretty puny for games that could routinely attract 30,000 or more fans. The lines and backup would be massive.

But at the same time, if 5,000 Dodgers fans came by gondola, that’s almost 10 percent of a sellout crowd. That 10 percent reduction in traffic and parking volumes could be significant for the team and fans who drive.

The A’s gondola plan would have the additional benefit of providing year-round service to the shops, bars, and homes at Jack London Square. Chavez Ravine, by contrast, is a parking lot wasteland when there aren’t events going on. So that should be a mark in favor of the A’s plan, as the gondola there might be more likely to have sufficient ridership year-round to justify the costs.

Either way, both of these proposals appear to have private backing, which means taxpayers wouldn’t necessarily be on the hook. If the gondola option can work logistically and financially, it could be an interesting transit option for baseball fans — and potentially be a transit boon for the surrounding neighborhoods, too.

Transit ridership is declining nationwide, while driving miles are up. Recent research indicates that increased access to vehicles by lower-income residents is particularly responsible for the transit dip, as lower-income residents tend to ride transit more than higher-income earners. And land use policies that encourage or force low-income residents to move far from jobs may be a determining factor.

First off, as Governing reports, poor people are increasingly able to access vehicles:

Only 20 percent of adults living in poverty in 2016 reported that they had no access to a vehicle. That’s down from 22 percent in 2006, according to a Governing analysis of U.S. Census data. Meanwhile, the access rates among all Americans was virtually the same (6.6 percent) between those two years.

In addition, lower-income earners are now able to get easy access to car loan services, including “subprime” auto loans.

But while economic factors play a role, so does land use:

“The country is becoming more car-oriented, because the country is moving south. If you’re moving from transit-oriented cities in the Northeast and moving to Texas, you’re going to become more car-oriented,” [urban planner and transportation consultant Sarah Jo Peterson] says.

Urban planners who want to push for walkable neighborhoods and transit-oriented development can still make a compelling case for certain areas, particularly urban centers, she says. “What they don’t have is wind at their backs.”

This migration of poor families to the suburbs, where housing is cheaper but transit service is weak, requires them to purchase an automobile to get access to jobs.

In Los Angeles, the Southern California Association of Governments commissioned a study by UCLA researchers on the causes of the ridership decline. The numbers from the report [PDF] are striking in terms of how concentrated transit ridership is in L.A.:

Ten percent of all of the people who commuted to and from work on transit in 2015 lived in 1.4 percent of the region’s census tracts, which covered just 0.2 percent of the region’s land area; the average number of transit commuters in these few tracts was almost 12 times the regional average. Fully 60 percent of the region’s transit commuters lived in 21 percent of the region’s census tracts, which occupied 0.9 percent of the region’s land area. Overall, the most urban and transit-friendly neighborhoods in the SCAG region comprise less than one percent of the region’s land area.

Areas that were heavily populated with transit commuters in the year 2000 became, in the next 15 years, slightly less poor, and significantly less foreign born. Perhaps most important, the share of households without vehicles in these neighborhoods fell notably. All these factors align with a narrative where a transit-using populace is replaced by people who are more likely to drive.

So while researchers are still analyzing the various causes for the ridership decline, the fact that low-income residents are moving to exurban areas may be a prime reason. And that displacement is likely due to high housing costs and gentrification in our prime transit areas. Until we solve that problem, we may not be able to resuscitate the nation’s transit systems anytime soon.

The Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach bring more goods into the U.S. than any other ports in the country. Yet together the ports are the single largest source of air pollution in Southern California.

The Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach bring more goods into the U.S. than any other ports in the country. Yet together the ports are the single largest source of air pollution in Southern California.

Harbor commissioners have adopted an ambitious plan to transition to cleaner fuels for goods movement in and around the ports in the next two decades. But achieving the vision for clean air will require answers to important questions:

- What are the prospects and potential for various zero-emission technologies – including battery electrification – to reduce pollution?

- How can finance, permitting and community engagement support the transition to cleaner fuels?

- What new policy and industry actions are needed for cost-effective deployment?

To address these questions, UCLA Law and UC Berkeley Law, with sponsorship from Bank of America, are hosting a free, daylong conference at UCLA Covel Commons on June 8, 2018. Panelists will examine the prospects and policy needs to move to a zero-emission future of goods movement in and around the ports. Speakers include the president of BYD Motors, CEO of ProTerra, CEO of Total Transportation Services, Inc. (TTSI) and CEO of the Coalition for Clean Air.

Also included will be representatives from:

- Bank of America

- California Trucking Association

- Earthjustice

- Port of Long Beach

- Southern California Edison

- Tesla Motors

- Union of Concerned Scientists

They will focus on steps that industry, government and civil society leaders must take to achieve zero-emission goods movement at the ports.

The event is free and open to the public, but advance registration is required, as space is limited. Please see the agenda and registration for more information.

Hope to see you there!

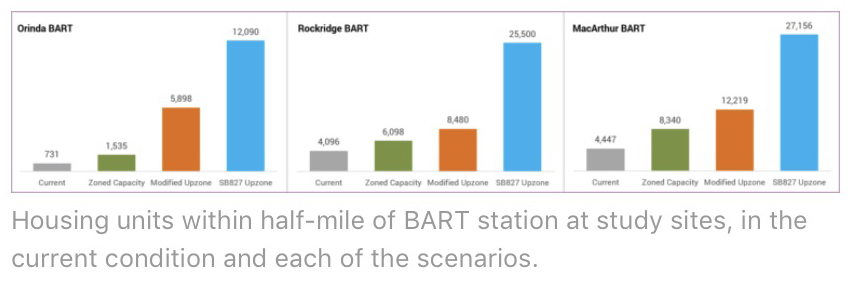

California State Senator Scott Wiener’s SB 827, to relax local restrictions on housing adjacent to transit, is a revolutionary step in the history of California land use. The initial version of the bill was clearly an opening salvo, reflecting a general statewide principle that locals should no longer squash housing in prime transit areas.

So it was inevitable that the legislative process would chip away at this broad framework, sometimes for good (recognizing that context matters in a state as large and diverse as California and that some changes might actually improve implementation and achievement of the larger goals) — and sometimes for bad (appeasing key legislators who don’t care much about building new housing near transit, to get their votes).

And now the first significant round of amendments were just introduced last night as the bill faces its first committee hearing and vote, with the promise of potentially another dozen rounds of amendments as SB 827 works its way through Capitol hearing rooms.

Below is the rundown on amendments, as Senator Wiener outlined in an accompanying Medium post. I’ll start with the good (or at least not horrible) and end with the unfortunate.

Good or Harmless Amendments:

- No net loss of affordable or rent-controlled housing provision: if a developer seeks to use SB 827 to build on a site with rent-controlled or subsidized affordable housing, the developer must replace each of these units with a permanently affordable housing unit on a 1:1 basis. This is a good provision because a loss of low-income residents near transit is not only unfortunate for those residents, it undermines transit usage. Low-income residents tend to use transit more than upper-income people. So we don’t want a situation where 30 low-income residents are replaced by 30 affluent residents under the bill. Otherwise, there could be a net loss in transit ridership and usage.

- Scale back qualifying bus stops: in its original form, SB 827 would apply equally to rail transit stops and any bus stop with 15-minute headways during commute hours. The provision might have been too generous, as many bus stops may have those headways during commute times but otherwise don’t provide enough service to truly allow car-free living for those nearby. The amendments now make the bill apply only to transit stops that have “consistent, high-quality transit during the week and on weekends, from early morning to late night.” Specifically, they must have at least 20 minute average service intervals between 6am and 10pm and 30 minute intervals on weekends from 8am to 10pm. The upside is that we won’t be building a lot of homes near transit stops that don’t really provide sufficient service to allow car-free living (or at least significantly reduced car trips).

- New residential percentage thresholds: any project under SB 827 must now be at least two-thirds residential by square footage.

The Not Terrible Amendments:

- Restriction on demolitions: a developer could not use SB 827 to demolish a building if the properties have had an Ellis Act eviction (kicking rent-controlled people out of their units with legal justification) recorded in the last five years. This provision provides an additional disincentive for property owners to evict rent-controlled residents, beyond what’s already in the bill. As with the “no net loss” provision, it might reduce the chances of displacement of low-income residents.

- Scale back relaxation of parking minimums: high parking requirements are a major disincentive to more dense development and essentially a tax on all homebuyers and renters. One of my favorite parts of the bill was that it eliminated parking requirements for any project within .5 mile of transit. But the new amendments allow cities to impose a .5 parking spot requirement per new residential unit in the .25 to .5 mile zone around transit. A developer must also provide recurring monthly transit passes to all residents at no cost. I don’t love the scaling back of the parking provision, but .5 in this outer radius is still a win. It mirrors the big parking victory under AB 744 (Chau, 2015), sponsored by the Council of Infill Builders, which reduced parking minimums to .5 for all affordable housing projects near transit, including in the 0-.25 mile zone that SB 827 relaxes completely. I’ll file this change as “not terrible” for now, barring any future weakening.

The Unfortunate Amendments:

- Lower height restrictions: the original bill allowed construction up to 85 feet within .25 miles of transit, under certain conditions. Now, around rail and ferry stations, only buildings up to 55’ tall can be permitted in the first .25 mile and 45’ in the second .25 mile zone. Furthermore, no building height increase will take place around any qualifying bus lines. The one upside is that parking and density restrictions will still be relaxed. For me, reducing the height limits means fewer units will be built, which is too bad. But if I had to give on either density, parking or height, I would probably give up on height, among the three. Density relaxations can help make up for many of the lost units that would have been built in the upper stories.

- Requirements to include affordable housing: it was pretty clear that SB 827 would have to include some kind of affordable housing mandate to pass, and here it is. If a community does not have a local “inclusionary housing” requirement (i.e. mandate for any market-rate developer to include some affordable units), the amendments offer a detailed set of options for developers to comply, ranging from 20% inclusionary if it’s a 50+ unit building to 10% low income or 5% very low income for 10-25 units. I don’t like inclusionary zoning because it’s a tax on new homebuyers and renters and not an equitable way to fund affordable units. It also depresses home production. A more equitable way to build affordable housing is through property taxes or broad-based taxes or bonds. But as far as things go, this isn’t a horrible formula.

- Delay of implementation by 2 years: SB 827 was set to go into effect this coming January 1st, if it passes. Now the operative date is two years later on January 1, 2021. A local government can also apply for a one-time, one-year extension if they can “prove to the Housing and Community Development Department that they have made significant good-faith progress.” The argument in favor is that local governments will have more time to “conduct studies, update inclusionary housing ordinances, and adopt specific transit oriented development plans.” Cities also won’t be able to use the time though to reduce or eliminate residential zoning to avoid SB 827 requirements. I don’t like the delay for two reasons: first, we need to get going on new home building right away, and local compliance with SB 827 really shouldn’t be that complicated. Second, I worry this gives opponents time to figure out a counter-strategy, or at least delay other needed measures to boost housing under the guise of “let’s see what happens in 3 years when SB 827 is finally in effect.”

Overall, a half a loaf is better than no loaf, and SB 827 is still a no-doubt landmark bill, even with these changes. The big worry is what happens in future rounds as more legislators require appeasement for their votes. But advocates can cross that bridge when they come to it. The main thing at this point is ensuring that there are still bridges to cross, with a worthy bill. And these amendments keep that effort going with only some loss and even some gain.

The great California housing debate over SB 827 (Wiener) has mostly been depressing to witness. The bill would essentially upzone areas adjacent to major transit, leading to badly needed housing production mostly in our affluent and transit-rich areas that can support more expensive multifamily construction.

Riding to the rescue of anti-growth affluent communities have been various advocacy groups focused on or allied with low-income tenants. These advocates mistakenly assume that the upzoning will lead to a building boom in low-income areas and contribute to gentrification and displacement. In reality, the upzoning will encourage development in high-rent areas and reduce pressure on displacement and gentrification overall.

So it was somewhat refreshing to see an advocacy group actually engage with the substance of SB 827, rather than react ideologically against it. TransForm has been focused on bolstering smarter land use around transit since it originally formed as the awkwardly named Transportation and Land Use Coalition (TALC) over 20 years ago. SB 827 in many ways should be the organization’s dream bill, as it seeks to reverse the exclusionary, low-density housing policies that have created the environmental and economic mess that California now finds itself in.

But TransForm is not entirely pleased with the bill. Their concerns revolve around preventing displacement of low-income residents, adding more affordable housing, and engendering a backlash against infill. In a blog post, they recommend:

- Value capture to increase affordable housing stock, likely through a requirement that a certain percentage of homes built under the bill be affordable (scaled to the size of the project)

- Stronger, enforceable renter protections, such as through ensuring no net loss of affordable housing in transit station areas

- More inclusive conversations about potential improvements

- Greater sensitivity to local context, such as different height limits on different land use types

- Consider “Missing Middle” housing types for low-density neighborhoods, such as designs that get over 80 units per acre with 25- to 30-foot buildings

- Place a maximum unit size on developments to avoid vertical McMansions

- Refine criteria for transit capacity, with different requirements for zoning based on transit types — BART, light rail, bus rapid transit, ferry, etc.

- Ensuring traffic and climate benefits by avoiding traffic congestion through parking maximums, providing on-site transportation amenities for residents, and maximizing affordability

- A clearer understanding of the bill’s geography and impact

Some of their recommendations are relatively harmless, such as a more inclusive process (which is what the legislative process is usually all about anyway) and better mapping. Some seem likely to engender the backlash they fear, such as parking maximums. And some seem overly fear-based, such as the need to “protect” single-family home neighborhoods to avoid a backlash — as if there isn’t already a big backlash against any new development.

In particular, it’s worth looking at differentiating land use requirements in the bill based on transit capacity, as well as increasing the enforceability of anti-displacement measures.

But TransForm should acknowledge that efforts to require more affordable housing through inclusionary zoning, even just in upscale areas, are essentially a tax on new housing to pay for more affordable units. This tax will depress housing production overall and put the burden of subsidizing affordable housing on new home buyers, rather than on existing homeowners who benefit from the status quo. Density bonuses would make more sense to boost affordable housing supply, as well as funding these units through increased taxes on current homeowners.

Still, it’s nice to see some substantive critiques from a land use advocacy group, particularly given how unproductive the nonprofit sector has generally been when it comes to finding actual solutions to the housing shortage. We’ll have to stay tuned to see if any of these recommendations make it into the bill.

California’s freight system is massive. Nearly 1/3 of all jobs in the state are in freight-related fields, and nearly 40% of all cargo moved throughout the United States enters or originates in California. The state’s seaports, airports, international border crossings and thousands of miles of rails and roads are integral to not just the state but the local, national and international economies.

California’s freight system is massive. Nearly 1/3 of all jobs in the state are in freight-related fields, and nearly 40% of all cargo moved throughout the United States enters or originates in California. The state’s seaports, airports, international border crossings and thousands of miles of rails and roads are integral to not just the state but the local, national and international economies.

However, the ships, trains, trucks and equipment that move goods throughout California are also responsible for up to 50% of the most harmful air pollutant emissions and 6% of greenhouse gas emissions statewide.

In response to environmental and public health concerns, Berkeley Law’s Center for Law, Energy and the Environment (CLEE) is today releasing a report that details key barriers and priority solutions to making freight more sustainable. Delivering the Goods was informed by a CLEE-convened discussion last July with a group of state regulators, industry leaders and environmental advocates. The group focused on how to achieve the state’s sustainable freight vision.

CLEE is hosting a webinar at 10 am Pacific today with three freight system experts who will discuss the report’s key findings.

Among the top barriers the group identified were the need to:

- Increase local community buy-in for new freight-related infrastructure projects and new technologies;

- Construct more infrastructure supporting smart goods movement; and

- Facilitate sharing of data among industry members and regulators.

The report discusses a broad range of near-term and long-term solutions to these challenges, including recommendations for state leaders, industry participants and community groups. Such actions include:

- Transportation corridor management strategies, such as new vehicle charging stations, freight-dedicated highway lanes and dynamic lane management to facilitate deployment of efficient technologies like heavy-duty truck electrification and platooning;

- Public-private information sharing platforms that encourage member organizations to share and analyze common efficiency-related data while protecting valuable IP, which could inform comprehensive “sliver” pilot programs to track each good’s path from production to consumption and identify efficiency opportunities throughout the supply chain; and

- Expansion of workforce development initiatives, and high school and college supply chain management and logistics programs, to ensure that freight projects are linked to local economies.

Ultimately, developing the state’s future sustainable freight system will depend on sustained efforts by all stakeholders to increase community involvement and support, embrace and effectively regulate emerging technologies, fund and build supportive infrastructure, and collect and disseminate more data. An integrated, collaborative planning and policymaking process, discussed in detail in the report, will be essential to the success of these efforts.

The full report, available here, includes a complete discussion of these concepts and more solutions proposed by the expert group.

CLEE’s free webinar, starting at 10 am Pacific today, can be accessed here. Speakers include:

- Elizabeth Fretheim of Walmart

- Adrian Martinez of Earthjustice

- Chris Schmidt of Caltrans

Hope you can join us!

The new federal spending bill that just became law represents a big win for transit, clean technology and energy efficiency. Despite efforts by the administration to gut funding in all of these areas, a bipartisan majority in congress resisted.

Curbed covered the increased spending for transit:

The bill, which covers spending through the end of September, includes significant increases in transit funding. The Community Development Block Grant program, which many local governments have used to fund streetscaping, cycling, and pedestrian-friendly projects, would receive a significant boost, rising to $3.3 billion from the $3 billion allocated in 2017. Initially, President Trump’s budget called for eliminating the program.

In addition, the bill includes more money for Capital Investment Grants, which help pay for transit projects, increasing spending from $2.4 to $2.6 billion, and would allocate $1.5 billion for the TIGER Grant program, tripling the $500 million spent on the program in 2017. This Obama-era program has been a key tool used by state and local governments to fund new rail and transit expansions.

Notably, even Amtrak funding increased under the package.

Meanwhile, some of the most important research and clean energy programs at the Department of Energy were bolstered, as E&E reported [paywalled]:

Instead of eliminating the Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy, DOE’s innovation arm, the package increases funding to a record level of $353 million. The Weatherization Assistance Program, which Trump also wanted to kill, would get a more than $20 million boost to $248 million. The deal keeps state energy grants and the Title 17 Innovative Technology Loan Guarantee Program intact.

It also would increase funding for the Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, which Trump wanted to slash by more than half.

This is all good news, and it points to the bipartisan support for these key components of our climate mitigation strategies. There’s still a larger issue about the availability of long-term funding for these programs, given the massive deficits the federal government is running, particularly with the budget-busting tax cut passed last December. But for now, these programs are safe and even stronger, in a rebuke to the administration and transit and clean tech opponents.

Map of the regional connector. Staging area was by the 1st and Central station on the right.

What’s a transit line without a tunnel? For densely populated areas, digging a tunnel can bring badly needed new capacity to congested corridors, while promising quick speeds underneath crowded roads. Plus tunnels represent interesting engineering and construction projects.

So when Jody Litvak of LA Metro invited me for a tour of the regional connector tunnel last spring, I jumped at the chance. At the time, the regional connector was under construction underneath Downtown Los Angeles, as you can see in the map above. I wrote about tunneling in Railtown, my book on the history of Metro Rail (I actually devoted a whole chapter to construction). But I’d never seen it up close until this tour.

I met Jody and her team at the staging area near Alameda and 1st Street in downtown. Olga Arroyo helped arrange the details, Dick McClane was the lead tunnel operator, and Bill Hansmire, Gary Baker and Glen Frank came along for the tour. Dick helps control the tunnel boring machine from a command center that resembles a miniature air traffic control tower. He monitors and corrects the machine’s every moment, using a complex network of sensors.

Dick also helps oversee the workers who do the tunneling. They call themselves “miners” — not “tunnel stiffs,” as the original tunnelers called themselves who built Metro Rail back in the 1980s, as I wrote in Railtown. The work is not for everyone: the miners described to me how some first-time workers have panic attacks when they get in the tunnel and simply can’t do the work.

But the regional connector and other train tunnels are actually a luxury — in the tunneling world. Many tunnels they work on are tiny and go miles deep, such as for sewers or other pipe infrastructure. The workers have to journey in the whole way on a makeshift train, leaning over to speed through the narrow tunnel. By comparison, this was a big, convenient tunnel. But still, there’s no daylight down there, so it’s a challenging work environment, and the miners work long shifts — sometimes 24 hours, 5 days straight on multiple shifts (with downtime in between, of course).

As the tour kicked off, safety was a priority. We were outfitted with helmets and reflective gear and instructed on proper procedures in the tunnel. Upon approach, the first thing we saw was the multi-block, fenced-off project site. The main feature was a conveyor belt from the shaft below, bringing up dirt that probably hadn’t seen the light of day in centuries, to be hauled off to help bury landfills. It created a huge pile that was actually just a couple days’ worth of excavation (see photo to the left).

The crew used this staging area to avoid disruption to the community from truck traffic coming out of tunnel. All that dirt requires a lot of vehicles to move it out of the area. In fact, truck traffic could be a limiting factor on tunnel boring, even if Elon Musk and his “Boring Machine” could speed the physical tunneling process.

Also visible up above were stacks of preset concrete slabs to line the tunnels, along with temporary steel rails. The rails help bring materials in and out of the tunnel, as they are hoisted down by crane and brought into the tunnel by temporary rail cars to lay more track.

We then journeyed down from the staging area to the giant shaft in the shape of the eventual station box. It had steep, temporary stairs leading down to the future station bottom and tunnel entrance. At the bottom, we could start walking through the actual tunnel.

Getting close to the tunnel, we could see lots of utility lines through pipes above us, including an old aqueduct from original the original Pueblo settlement. As the workers told me, these “station boxes” are where they find all the archaeological finds. Otherwise, the boring machine pretty much grinds everything else up (although evidently the formation that the tunnel passes through doesn’t typically have archaeological finds). For more on the archaeological finds in the tunnel, check out this article.

Inside the tunnel, it was hot with an odd smell. It was loud, too, particularly when workers dropped new 30-foot steel rails to the ground. The rails were needed for the temporary cars that brought in equipment. The tunnel boring machine (“TBM”) itself was probably about 100 yards long. In fact, it was so long, I was walking through it for a while without even knowing it.

The TBM is operated by four people: an operator, engineer, and mechanic, along with an MTA inspector. The machines have sensors everywhere and are extremely high-tech, monitoring the ground movement above. The software can automatically brake the TBM if the machine starts going in the wrong direction. The TBM uses pressure within the tunnel to maintain the pressure in the ground around the tunnel as it’s bored. That stabilization reduces, if not eliminates, both ground subsidence and gas seepage into the tunnel. For example, at the time of the tour, we were directly under a Japanese market in Little Tokyo. Hopefully, the patrons up above had no idea what was going on below. Sometimes TBM workers have to tunnel quickly through some parts of the city, like through certain soils that aren’t as solid.

Progress was steady: the miners were clearing about 80 feet in one day, at an average of 65 feet. They were starting with just the “left” bore for now, drilling it out for one mile, then hauling the tunnel boring machine (TBM) back to the project site and reassembling it for the “right” bore in the same direction, to create two tracks for the line. Overall, the first tunnel was set to take 5 months to go the whole 5,000 feet, 2 months to reassemble, and then another 5 months for the other tunnel.

In terms of cost, the tunneling represented only 10% of the total project cost. The station boxes are the other big chunk of change, particularly the future Bunker Hill stop, because it’s so deep.

Overall, it was an interesting opportunity to see digging in action. The project is scheduled to be finished in 2021. Once I ride it, I’ll end up whizzing through the section I walked. But I’ll now know how much work went into building it.

If you want more tunnel tour accounts, check out Curbed.LA from July and then again last month.

I’ll be on KQED radio’s Forum this morning at 10am discussing SB 827 (Wiener) to relax local restrictions on transit-oriented housing. We’ll discuss what the bill might mean for California’s cities, environment and economy.

Please tune in at 88.5 FM in the San Francisco Bay Area and weigh in with your questions. Even if you don’t live in the Bay Area, you can stream it live.