As I began researching the history of the Los Angeles Metro Rail system for my 2014 book Railtown, one particular aspect of the rail transit story shocked me. No, it wasn’t the petty political squabbles, short-sighted civic leadership, or selfish parochialism that slowed, weakened and sometimes stymied the development of a functional rail system in Los Angeles. It was the shocking price tag of building rail transit — particularly tunneling under busy city streets — and the absurd amount of time (decades in some cases) to dig tunnels that more than a century ago were done in a fraction of the time it takes today.

Like the rest of the United States, Los Angeles suffers from exorbitant costs and delays with tunneling. The 1.9 mile Regional Connector light rail tunnel under downtown, for example, will cost almost $1.7 billion and take at least 8 years to complete. Nationwide, as transit expert Alon Levy has documented, tunneling costs are out of whack even compared to other developed nations, with New York City’s $2.6 billion-per-mile Second Avenue subway as a particularly gruesome transit horror story.

So I was intrigued this past December when I learned that Elon Musk’s Boring Company was unveiling a demonstration tunnel in Hawthorne, California, that could be built quickly and at a fraction of the cost. How cheap? 1.14-mile for just $10 million, with potential long-term improvements in speed of up to 15 times over the current rate.

Many urbanists sneered, deriding the tunnel as nothing more than a sewer pipe and mocking the idea of a “tunnel for Teslas” as simply recreating the failed surface roadway patterns of the present — or worse, catering to the wealthy by allowing them to avoid the congestion caused by the plebeians above.

Many of these same urbanists already resented Musk for his work with Tesla, a company which promotes a vehicle technology that they rightly identify as destroying our urban fabric, while he also (ironically) works to remove one of the arguments against cars by eliminating their tailpipe pollution.

But what if Musk and his rocket scientists from SpaceX really could bring down the cost and time of tunneling? Imagine the transit projects that could ensue. I’ll offer four, just here in California alone:

- A subway under Wilshire Boulevard in Los Angeles, the densest corridor west of the Mississippi, while Metro, the public agency currently trying to build one, is mired in a decade-long, multi-billion dollar slog.

- A subway connecting West L.A. with Sherman Oaks and the San Fernando Valley underneath the dreaded Sepulveda Pass and the freeway parking lot known as “The 405.”

- A second Bay crossing connecting Oakland and San Francisco to address congestion on BART and possibly allow one-seat train service from San Francisco to Sacramento.

- A tunnel connecting San Francisco to Los Angeles and San Diego, completing the dream of the flailing high speed rail project.

Those four projects alone would make any California urbanist happy. Yet how seriously can we take the Boring Company’s claims regarding decreased tunneling costs and time?

I took a tour of the test tunnel in Hawthorne last month to try to gain more clarity on how the company is reducing tunnel costs. Three things stood out:

- The Dirt. Believe it or not, what to do with the dirt that comes out of tunnels is a big limiting factor. I heard this first-hand from the tunneling experts working on the Regional Connector project under downtown Los Angeles. Yet the Boring Company may have found something simple and innovative to do with that dirt: turn them into functional bricks. To prove their point, they built a Monty Python-style tower out of the bricks on site. If the bricks can be given away for free, it will greatly reduce costs. If they can sell the bricks for use in things like sound walls, they say they could actually make money on the tunnel (see the picture above and video below of the dirt brick-making process).

- Private funding incentives. The Boring Company is envisioning a privately funded network of tunnels throughout California and beyond. They are not necessarily contemplating bidding on large public sector contracts. As a result, the company appears to have incentives to cut costs in ways that some of the few big tunneling companies competing for select large public contracts may not. As an example, the company can save costs simply in terms of where they manufacture the tunnel’s concrete segments relative to the tunnel, a cost-saving step that they say the big tunneling contractors aren’t financially motivated to take.

- Lots of little things. There appears to be no one single leap forward with the Boring Company machine. But instead, the company’s leaders say they’ve managed a series of smaller innovations that combined together could help reduce the costs dramatically. Perhaps most significantly, the tunnel bore has a smaller diameter than many rail tunnels because they don’t need the wiring and infrastructure that a train needs, but it’s still large enough to fit a vehicle with the carrying capacity of a subway train. Their vision is to run battery-powered, autonomous vehicle platforms in the tunnels, rather than hard wire expensive rail cars. It’s a vision of where technology is heading that could eventually lead to existing rail transit being converted to autonomous, battery-powered, platooning shuttles, which could carry the same passengers as rail but for a fraction of the capital and operating costs.

In any event, we’ll soon see if these company claims are accurate, as the Boring Company appears ready to work on a tunnel under the Las Vegas convention center soon.

And while urbanists fret about the potential for expanded subterranean capacity for solo drivers, there’s no reason that the technology would only be employed for that use and couldn’t scale to the level of current public rail transit. The company sees Model X battery-powered platforms seating between 16 and 32 passengers traveling up to 165 miles per hour through LED-lit tunnels. And with five boring machines in action, they think they could reach San Francisco in just a year. That vision — though of private and not public transit — would only bolster urbanist goals of car-free living in more dense, transit-oriented communities.

A big limiting factor though, beyond the technology, may be permitting. Environmental review under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) may slow this deployment. Under the law, permitting agencies will have to study and mitigate environmental impacts ranging from paleontology to induced land use changes and traffic at the surface entry points to the tunnel. We’ll see how that process plays out, if the Boring Company starts moving forward on a project in California.

But if Musk and his crew have actually solved the technology and cost problem of tunneling, they will have given transit backers throughout the United States and beyond a big reason to celebrate. Because a revolution in tunneling is a pipe dream worth pursuing in our increasingly urban world.

California’s massive housing shortage relative to population and job growth is only getting worse, and the state’s senate will be examining the issue today at a joint hearing of the Housing and Governance & Finance committees at 1:30pm in the Capitol. I’ll be testifying regarding the link between housing and greenhouse gas emissions.

The hearing comes as the San Francisco Chronicle ran a front page story this morning on the vast number of bills introduced this session to address the crisis. Most of the bills are aimed at high-cost, low-growth, job-rich areas, which are predominantly white and high income, filled with vocal residents who don’t want new growth in their exclusive communities.

Yet if California is to have any hope of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by decreasing driving miles, not to mention addressing the extreme segregation and economic inequality, the state will have to intervene in the face of these restrictive local land use policies.

You can tune in to the hearing and watch live here

It took five years, but California has finally ditched an outdated and counter-productive metric for evaluating transportation impacts under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). With the guidelines finalized on December 28th, a mere half-decade since the passage of SB 743 (Steinberg) in 2013, the state will ditch “auto delay” as a measure of project impacts and instead measure overall driving miles (VMT). You can see the new guidelines Section 15064.3.

It’s a big deal. Now new projects like bike lanes, offices, and housing will be presumed exempt from any transportation analysis whatsoever under CEQA if they are within 1/2 mile of major transit or decrease driving miles over baseline conditions. That means significantly reduced litigation risk and processing time for these badly needed infill projects.

Sprawl projects, meanwhile, will need to account for and mitigate their impacts from dumping more cars on the road for longer driving distances. Berkeley Law’s Center for Law, Energy and the Environment (CLEE) explored one such mitigation option in the form of a VMT “mitigation bank” or exchange in the recent report Implementing SB 743, where developers could pay into a fund to reduce VMT, such as for new transit or bike lane projects.

Sprawl projects, meanwhile, will need to account for and mitigate their impacts from dumping more cars on the road for longer driving distances. Berkeley Law’s Center for Law, Energy and the Environment (CLEE) explored one such mitigation option in the form of a VMT “mitigation bank” or exchange in the recent report Implementing SB 743, where developers could pay into a fund to reduce VMT, such as for new transit or bike lane projects.

The one caveat is that due to political pressure, new roadway expansions are exempt from this requirement under the guidelines. It’s unfortunate, but those roadway projects will still need to undertake VMT analysis anyway for climate and air quality impacts, so perhaps they are not as exempt as their backers hoped.

You can learn more about these changes and what they mean going forward at a March 1st conference that CLEE is co-organizing in Los Angeles with the Urban Sustainability Accelerator at Portland State University. Shifting from Maintaining LOS to Reducing VMT: Case Studies of Analysis and Mitigation under CEQA Guidelines Implementing SB 743 will be a professional educational program for land use, transportation and environmental planners and attorneys in public, private and nonprofit practice, presented by expert practitioners.

- When: Friday March 1, 2019

- Where: Offices of the Southern California Association of Governments, Los Angeles

Topics to be discussed include:

- VMT impact analysis (methodology; appropriate tools and models, determining impact area)

- VMT significance thresholds (project effects, cumulative effects)

- VMT significance thresholds (project, cumulative)

- VMT mitigation strategies (project level, programmatic, VMT banks and transaction exchanges, legal and administrative framework)

Space is limited to 70 people to attend in person; registrants can view the program online streaming concurrently or subsequent to the program.

Registration Fees:

- Free Staff of state, regional and local governments sponsoring the SB 743 implementation assistance project and of their member governments (use link below for information about affiliations qualifying for free registration)

- $30 General registration, not seeking professional education credits

- $90 Planners seeking 6 AICP credits* ($15/credit)

- $210 Attorneys seeking 6 MCLE credits* ($35/credit)

*The organizer has accreditation for six hours of California Mandatory Continuing Legal Education (MCLE) credits and is seeking accreditation for six hours of AICP credits.

You can learn more about this conference here and can proceed directly to the online preregistration form here.

Short answer: no. At least not the way they’re currently presented, as a single-track option for private vehicles with solo drivers. It’s the equivalent of building new roads on the surface: once you build them, traffic quickly increases to fill them.

Short answer: no. At least not the way they’re currently presented, as a single-track option for private vehicles with solo drivers. It’s the equivalent of building new roads on the surface: once you build them, traffic quickly increases to fill them.

However, if the tunnels improve their efficiency by squeezing more people into the vehicles, such as through shared rides or right-sized “pods” for individuals, then Musk’s tunnels could provide a significant benefit. But of course at that point they start to look exactly like a subway car, only with the cars replaced by Teslas.

Perhaps for this reason, many transit advocates are heaping scorn on Musk’s plan. They were also predisposed to resent Musk personally because he has criticized public transit in the past and has revolutionized passenger vehicles through battery electric technology, which some transit advocates mistakenly view as a threat to political support for expanding transit.

For my part, I don’t think it matters if Musk’s plan fails, since it’s a completely private venture. And if it succeeds, the public will benefit in multiple ways: from improved tunneling technology to new capacity to move people (albeit only those who can afford it) faster across town.

But I do have some “red lines” for my overall indifference to the venture:

- No public dollars should be spent on the project, unless there are commensurate public benefits. Essentially, the tunnels would have to be affordable to all and accessible to those who can’t afford a vehicle (i.e. function like traditional public transit).

- No public giveaways in terms of subsurface land rights. The tunnels should have to compete on a level playing field with public transit tunnels, in terms of these types of land costs. I’m otherwise okay with waiving some environmental review (i.e. transportation, aesthetic, and parking impacts, among others), as I would be with any other public transit tunnel.

- The tunnels should not interfere with public transit tunnels. That means the tunneling shouldn’t prevent future subway tunnel extensions, and the ingress and egress for the tunnels shouldn’t impede bus lanes and pedestrian access to transit, as well as critical transit-oriented development.

As long as the venture doesn’t cross those lines, I wish The Boring Company and Musk success and will hope for positive spillover for the general public. And I also wish that they fulfill the original vision of right-sized, shared vehicles in the tunnel that increase efficient use of space and decrease incentives for solo driving.

Given Musk’s commitment to averting climate change, that’s a vision I think he’d support.

The Boring Company Loop system pic.twitter.com/xVpDHzZKXB

— The Boring Company (@boringcompany) December 19, 2018

Elon Musk may have just disrupted another industry. In this case, it’s transportation tunneling. His Boring Company last night unveiled a 1.14-mile “proof-of-concept tunnel” in Hawthorne at a cost of $10 million (see Twitter video above).

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/62706193/Boring_tunnel__2.0.jpg) As Alissa Walker described in Curbed LA after attending the launch, the tunnel features a track for a Tesla to drive underground, as a sort of subway transit for private vehicles. While the tunnel is getting a lot of press, transit advocates have concerns about how effective this type of private transport might be.

As Alissa Walker described in Curbed LA after attending the launch, the tunnel features a track for a Tesla to drive underground, as a sort of subway transit for private vehicles. While the tunnel is getting a lot of press, transit advocates have concerns about how effective this type of private transport might be.

But perhaps more important is Musk’s potentially significant advancement in tunneling technology, which could offer major benefits for subway tunneling everywhere (and maybe even please those same pro-transit critics).

Bloomberg summarized the engineering progress:

Musk said that the advances his team has made in tunneling technology would increase the speed of boring underground by up to 15 times. The company will do that largely through tripling the power of the drill itself, he said, and through logistical interventions such as building segmented reinforcements in the tunnel walls while continuing to drill.

Given the numbers that Musk reported last night, he may have netted significant results, with a relatively minuscule price of $10 million for 1.14 miles.

By comparison, recent per mile tunneling costs around the country have been staggeringly high, as Alon Levy noted in CityLab. For example, New York City’s recent Second Avenue Subway clocked in at an astounding $2.6 billion per mile. San Francisco’s central subway and Los Angeles’s regional connector subways are not much better, at $920 million per mile, while the L.A. Purple Line subway may cost $800 million per mile. That means these major transit system tunnels are costing as much as 100 times more than Musk’s prototype tunnel.

But are we comparing apples to apples? Not really. The costs described above include much larger diameter tunnels, as well as station “boxes,” utility relocation, ventilation, and safety features, among others. As Alon Levy calculated back in 2017, even in a best-case scenario with cheaper “cut and cover” station boxes, U.S. subway tunneling would likely still cost $500-600 million per km ($800-$960 per mile). Musk’s tunnel by contrast is quite bare bones, with no station boxes or complex systems and space for only one vehicle.

For a better comparison, we can look to Laura Nelson’s reported numbers for the Purple Line heavy rail extension in the Los Angeles Times. She described back in June the tunneling contract for the 2.59-mile extension from Century City to West Los Angeles, which is projected to cost $3.59 billion total. But the actual tunneling contract is smaller: $410-million for a four-year design and construction contract to Tutor Perini. So the costs just for tunneling (assuming these numbers will be accurate, which is doubtful based on past experience) will be $158 million per mile, not including land acquisition and moving utility lines.

But that $158 million per mile is still 15 times the cost of Musk’s Boring Company tunnel.

Ultimately, more analysis and investigation will be needed to understand how the costs for Musk’s single-track tunnel might compare to a large-scale, twin-bore subway tunnel with all the safety, lighting, and ventilation features that we see in big urban transit projects.

But the early numbers indicate that Musk may have just achieved a significant breakthrough in reduced tunneling costs, with major benefits for transit everywhere.

The California housing debate took me to KQED-TV’s “Newsroom” program on Friday. You can watch my discussion with host Thuy Vu and State Sen. Scott Wiener, author of SB 50 to upzone areas near major transit, at the 18-minute mark:

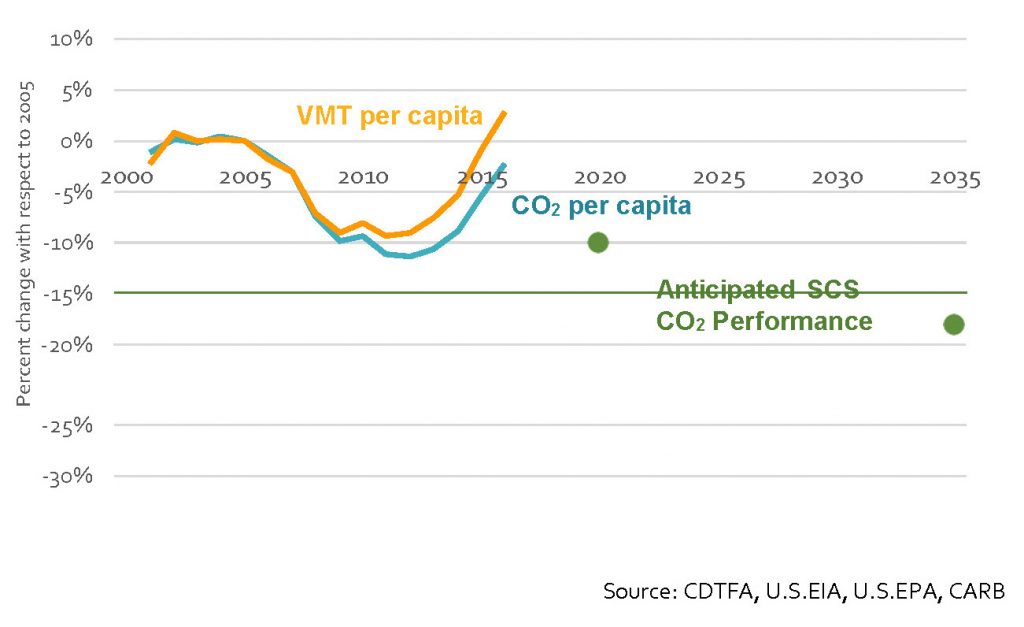

California’s major urban regions are falling behind in getting people out of their solo drives in favor of walking, biking, transit and carpooling, according to a major report last month from the California Air Resources Board. In short, the state will not meet its 2030 climate goals without more progress on reducing vehicle miles traveled (VMT):

This result comes despite the decade-old passage of SB 375 (Steinberg, 2008), which promised to reorient land use and transportation around reduced driving. The lone exception appears to be the San Francisco Bay Area, which has seen steadily increasing transit ridership and decreasing solo driving to work as a percentage, according to the report.

This result comes despite the decade-old passage of SB 375 (Steinberg, 2008), which promised to reorient land use and transportation around reduced driving. The lone exception appears to be the San Francisco Bay Area, which has seen steadily increasing transit ridership and decreasing solo driving to work as a percentage, according to the report.

What are the stakes if California can’t start solving this problem in the next decade? A U.N. report on climate change recently concluded that limiting global warming to 1.5 C would “require more policies that get people out of their cars — into ride-sharing and public transportation, if not bikes and scooters — even as cars switch from fossil fuels to electrics.” In order to keep the world on track to stay within 1.5 Celsius, the report stated that emission reductions would have to “come predominantly from the transport and industry sectors” and that countries couldn’t just rely on zero-emission vehicles alone.

Yet as the report shows, California’s current land use policies are not helping with this goal. We need to discourage development in car-dependent areas while promoting growth close to jobs, as SB 50 would allow. And at the same time, we need to invest in better transit service. Otherwise, California and jurisdictions like it around the world will fail to avert the coming climate catastrophe.

Climate change exacerbates the droughts, floods, and wildfires that Californians now regularly experience, making them even more extreme and unpredictable. Gavin Newsom, California’s next governor, faces the urgent challenge of simultaneously preparing for inevitable disaster, improving the quality of life for residents, and minimizing the greenhouse gas emissions of a society of nearly 40 million people.

Climate change exacerbates the droughts, floods, and wildfires that Californians now regularly experience, making them even more extreme and unpredictable. Gavin Newsom, California’s next governor, faces the urgent challenge of simultaneously preparing for inevitable disaster, improving the quality of life for residents, and minimizing the greenhouse gas emissions of a society of nearly 40 million people.

In that spirit, UC Berkeley School of Law’s Center for Law, Energy & the Environment (CLEE) and Resources Legacy Fund (RLF) have given Governor-Elect Gavin Newsom three detailed sets of actions he can take immediately to address wildfire and forest management; drought, flood, and drinking water safety and affordability; and the stubbornly high carbon pollution of our transportation systems.

Specific recommendations include:

- Creating comprehensive, data-driven maps that identify the highest-risk wildfire areas to help the state target investments in emergency response programs and vegetation treatment;

- Accelerating the consolidation of small water systems in disadvantaged communities that consistently do not receive adequate supplies of safe drinking water; and

- Giving local governments incentives to change commercial zoning to increase transit-accessible, affordable housing and reduce the number of miles people drive.

The report also recommends creating incentives for local governments to limit development in high-risk fire areas, designing a system that dedicates a volume of water for the environment to be managed for ecosystem recovery, and setting stringent housing, transportation and greenhouse gas reduction criteria for cities looking to expand or change their boundaries.

Each set of recommendations arose from separate, half-day symposia involving a dozen or more practitioners and experts with perspectives on wildfire, water, and the nexus of climate change, housing, and transportation. Experts included local government officials, former state agency heads, environmental advocates, industry leaders, and academic researchers.

RLF and CLEE organized the panels, moderated by me and Sacramento Mayor and former Senate President pro Tempore Darrell Steinberg. Despite often divergent perspectives, panelists worked to find agreement on near-term actions. After the discussions, CLEE and RLF distilled the top recommended actions with participant input.

RLF and CLEE delivered the recommendations to Governor-Elect Newsom, Chief of Staff Ann O’Leary, and Cabinet Secretary Ana Matosantos last week.

A few themes emerged in the discussions and recommended actions:

- Cities and counties hold primary authority for deciding whether people live in harm’s reach of wildfire, drought, or flood and whether they can get to jobs and services without long vehicle commutes. Wherever possible, the state should use incentives to spur local government actions that align with statewide goals such as reducing vehicle emissions or hardening communities against fire risk. But some situations – such as the provision of clean drinking water – warrant state regulation.

- The new governor should align the way state agencies spend money in order to achieve his priorities. Federal and state transportation dollars, for example, should be directed to projects that help reduce the number of miles people drive.

- Strong leadership and systematic coordination from the governor’s office are crucial to driving progress across departments toward a common goal. The new governor should appoint leaders in each area who can spearhead cohesive, rapid action across agencies and throughout state government.

The specific recommendations and panel members can be found here. Hopefully these recommendations will help the new governor and the public be better prepared for the environmental threats we face in California.