California State Senator Scott Wiener launched his third legislative attempt today at boosting California’s housing supply. SB 50 aims to address the state’s massive housing shortage, which has resulted in high home prices and rents, gentrification, displacement, inequality, homelessness, and a mass middle-class exodus to high-emission states like Texas and Arizona.

Because this housing undersupply is caused primarily by restrictive local land use policies in the state’s coastal job centers, Wiener’s approach has been to require cities and counties to allow apartment buildings near major transit centers. His first attempt in 2018 (SB 827) died quickly in committee. His second attempt last year (the birth of SB 50) was unilaterally shelved for a year by State Senator Anthony Portantino, who represents the affluent Southern California city La Cañada Flintridge (that city quickly became a poster child to housing advocates for high income single-family homeowners who don’t want to allow new residents in apartments into their neighborhoods).

The clock is now ticking on SB 50 in 2020. Under legislative rules, the bill must pass the full Senate by the end of this month — and first make it out of Sen. Portantino’s committee.

So Sen. Wiener is trying again, unveiling at an Oakland press conference this morning a critical amendment to delay statewide implementation for two years in order to give local governments the opportunity to develop their own plans that meet or exceed the housing, equity and environmental goals of SB 50. Otherwise, SB 50’s provisions relaxing height, parking and density requirements around major transit stations will automatically prevail.

Specifically, the state (through the Governor’s Office of Planning and Research) will develop guidance for these “local flexibility plans” by mid-2021. Cities and counties must then submit their plans for approval to the California’s Department of Housing and Community Development. That agency will then certify that the local plans are as stringent as SB 50. The local plans must be in place by January 1, 2023 in order to avoid defaulting to SB 50 statewide standards.

Otherwise, the substance of the bill remains essentially unchanged from last spring (here’s my rundown on the last changes before Sen. Portantino shelved it).

These new amendments seek to mollify critics who complained that the statewide approach undercuts local flexibility to meet the targets in a more tailored way. For example, rather than having uniform four-story apartment buildings around a major transit stop, perhaps a city would prefer to meet the overall housing production goals with a taller building in one spot and a shorter building across the street.

Will these changes be enough to satisfy local government objections? Probably not in many cases. The objections are less about local control and more about visceral dislike for apartment buildings and the residents they may bring. Arguments about local control — and relatedly against market-rate housing and instead building only subsidized affordable units — are often not made in good faith. Critics quickly move the goal posts as soon as amendments are made in their direction.

Take for example Sen. Portantino’s initial reaction to these amendments, complaining about not enough affordable housing, per his spokesperson to the San Francisco Chronicle:

“It was the senator’s hope that by taking a breath with SB50 it would focus efforts on actually building affordable housing as opposed to the market-rate housing predominant with SB50.”

This comment ignores that SB 50-type reform would result in the biggest boost to subsidized affordable units in the state’s history, at possibly a seven-fold increase. All without raising taxes or issuing bonds, and without delay about where to build these units even if public funds are available.

Still, these amendments may persuade critics who are on the fence. And perhaps most critically: will Governor Newsom now throw his weight behind the measure to help it pass? This is a big test for the governor on one of his signature campaign issues.

All in all, the next few weeks will be instructive as to whether or not California leadership can meaningfully address the the housing shortage and its severe equity, economic and environmental consequences.

The California Preservation Foundation is hosting a webinar debate today from 11am to noon on the housing shortage, entitled “Point-Counterpoint: Streamlining Housing Development vs Local Control.” I’ll be on the pro-housing side against a few prominent “local control” anti-housing advocates.

Moderated by Diane Kane, PhD (Emeritus Trustee at the California Preservation Foundation), the panelist debaters include:

- Barbara Bry, City Councilmember, City of San Diego

- Todd David, Executive Director, San Francisco Housing Action Coalition

- Ethan Elkind, Director, Climate Program, Center for Law, Energy & the Environment, U.C. Berkeley

- Dennis Richards, Planning Commissioner, City of San Francisco

The questions will cover issues like CEQA’s effect on housing production, NIMBY motivation, how historic preservation affects the shortage, and if single-family homes are inherently a ‘bad’ thing.

You can register here (registration is $40 for members and $60 for non-members) to join the webinar and ask your questions of the panelists.

The future of California’s high speed rail system has arguably never been as perilous as now. Otherwise-supportive legislators are now openly mulling raiding high speed rail funds meant to complete the first leg in the Central Valley for rail improvements in the more densely populated parts of California, namely the San Francisco Bay Area and Los Angeles to Anaheim, as the Los Angeles Times recently reported. Governor Newsom also expressed a lack of confidence in the system during his “State of the State” speech, in which he offered an abrupt scaling back of the state’s vision for its signature infrastructure project.

Following that February speech, the governor appointed Lenny Mendonca as the new California High Speed Rail Authority chair, whom I’ll interview tonight on City Visions on NPR affiliate 91.7 FM KALW radio in San Francisco, from 7-8pm. (For those out of the area, you can stream it or listen to the archived broadcast after the show here.) Mendonca has since laid out a vision for a down-sized “building block” segment from the Central Valley cities of Merced to Bakersfield, which could temporarily serve diesel-powered Amtrak trains until funding materializes for a segment from Merced to the Bay Area — and one day through the Tehachapi Mountains to Los Angeles.

This scaled-back plan is in some ways a simple nod to fiscal reality. There aren’t enough funds right now to complete the project beyond this initial phase in the Central Valley. Voters approved roughly $10 billion in bond funding in 2008, the 2009 federal “stimulus” bill offered another $3.5 billion ($1 billion of which the Trump Administration is now trying to cancel), and former Governor Jerry Brown and the legislature dedicated about 25% of the state’s cap-and-trade auction proceeds to continue building the system. But that’s not enough money to connect the Central Valley portion through the Pacheco Pass into San Jose, where it could then connect to the soon-to-be-electrified Caltrain into San Francisco. And it’s nowhere near the multiple billions of dollars needed to tunnel through the Tehachapis to connect to Southern California.

Despite cost overruns and some controversial decision-making by some state leaders, the key stumbling block has mostly been the federal government. Republicans in control of Congress from 2011 to 2019 were unwilling to match the state’s investment with federal dollars. If California had received at least a 50% match in federal funds (the typical match rate for urban rail transit projects), the rail system would have the money today to connect to the Bay Area, while at least making critical rail improvements in the Southern California section, if not starting the tunneling effort to Los Angeles.

So will high speed rail supporters ultimately need a change in leadership in Congress and the White House to get the necessary funds to complete the project? Will the California Legislature abandon the project and use the remaining dollars on local rail improvements instead? How useful will the scaled-back “building block” segment in the Central Valley be, absent further rail connections?

I’ll ask Chair Mendonca for his thoughts on these questions tonight, as well as for an update on the current status of the project. Listeners can call in at 866-798-TALK or email question as well. With the future of the nation’s only high speed rail project under construction now in the balance, and a new governor and leadership team at the helm, this project is truly at a major crossroads.

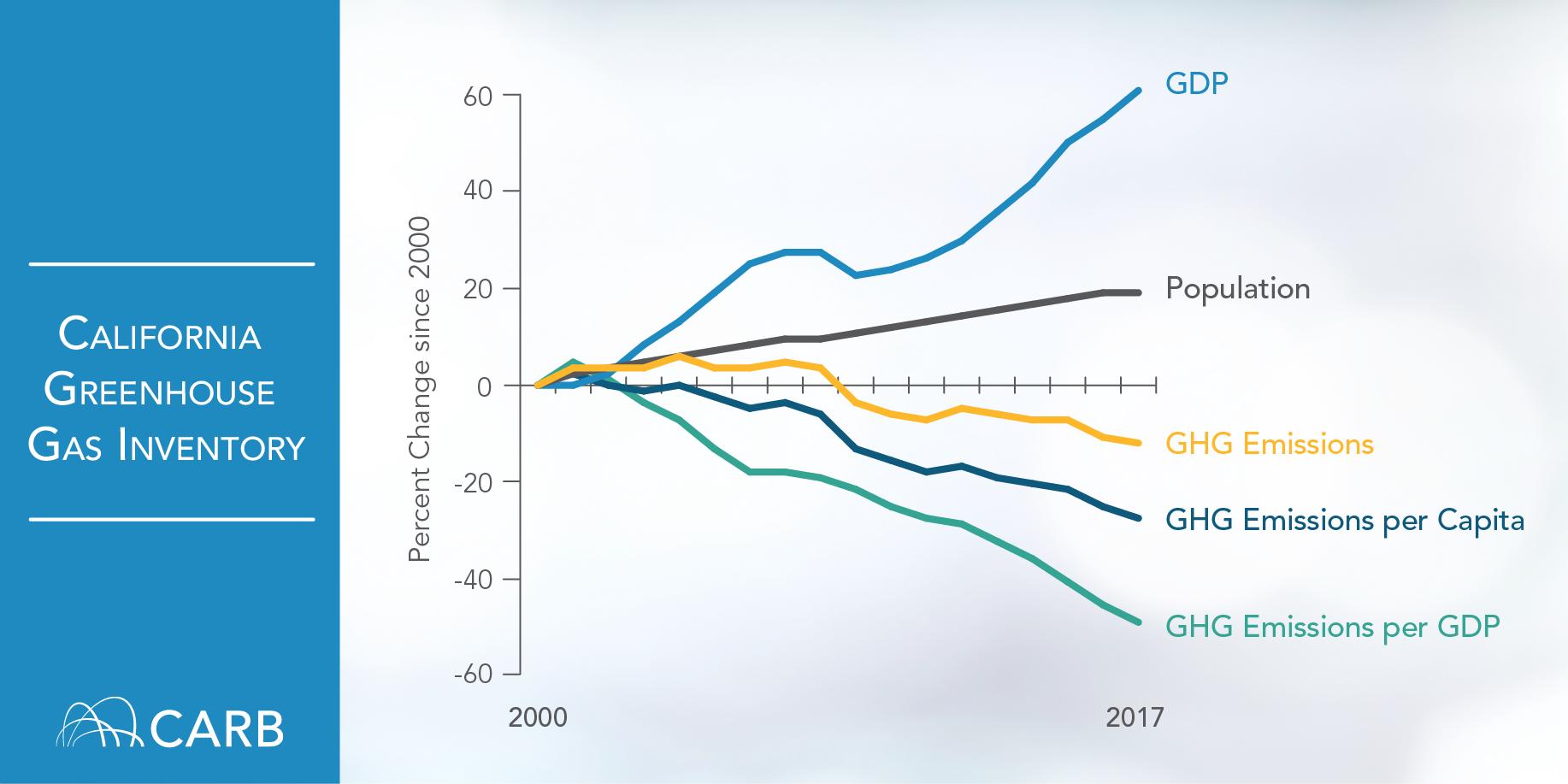

Good news on California’s efforts to fight climate change: in-state emissions in 2017 (the latest available data) were down over 2016 and ahead of the state’s mandatory 2020 goals. The California Air Resources Board announced the progress yesterday, with this chart showing emissions in context of population and GDP:

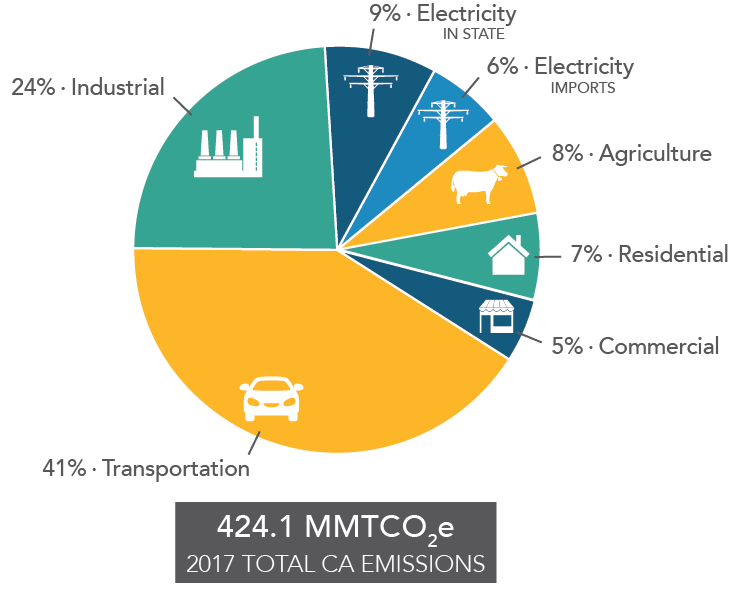

Overall, emissions totaled 424 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent in 2017, down 5 million metric tons from 2016. For reference, the 2020 reduction target is 431 million metric tons.

Most of the progress came from the electricity sector, where for the first time renewable sources made up a larger percentage of the generation than fossil fuels.

However, transportation emissions increased 0.7% in 2017, compared to a 2% increase in 2016, mostly from passenger vehicles. That total is even worse when you consider pollution from oil and gas refineries that make the fuel for these passenger vehicles. Together with hydrogen production, these sources constituted one-third of the state’s total industrial pollution.

Here’s the latest pie chart on where the emissions came from in 2017:

While the story is overall positive for California’s climate efforts, the state will have to redouble its efforts to reduce driving miles by allowing more homes to be built near jobs and transit, while transitioning the remaining driving miles to zero-emission technologies like electric vehicles.

Many urbanists, environmentalists, and transit enthusiasts love rail. Los Angeles voters in particular have repeatedly expressed the wish for more rail, approving county sales tax increases by overwhelming margins in 2008 and 2016, along with prior measures in 1980 and 1990, in part to fund a nation-leading, multi-billion dollar rail transit build out (a history I documented in the 2014 book Railtown). Many other cities around the country also either have mature rail systems or are in the process of building new ones.

But as I wrote last year, what if this nineteenth century mode of transit propulsion is about to be made obsolete? Specifically, self-driving, battery-powered platoons of electric buses have the ability to achieve all of the same benefits of fixed rail transit, but at a fraction of both the capital and operating cost. If we can place 8 or 10 buses in a row (platooning means they would drive in sync as if hitched together, based on self-driving sensors), have them all accelerate electrically and brake together, be separated by just a few inches, and be operated by just a single lead driver or computer, isn’t this essentially just a long train?

It’s a question I look forward to posing in a conversation I’m moderating with LA Metro CEO Phil Washington at an upcoming Council of Infill Builders “LA Infill” conference, co-sponsored and hosted by UCLA Law on Wednesday, July 24th.

Here are some of the typical benefits of rail and how self-driving, platooning electric buses (e-buses, or automated rapid transit, ART) could compare:

- Capacity: a 10-car train can pack a lot of people, often making the ride more cost-effective to operate per passenger than single trains and buses. But platooning e-buses of up to 10 or more in a row could carry the same capacity as a crowded rail car and could be designed to look and function exactly like rail cars.

- Fast electric acceleration: rail is a smoother ride than diesel or gas-powered buses, with fast electric propulsion. But e-buses provide the same acceleration benefits.

- Fast and reliable service: rail transit in dedicated rights-of-way (required for heavy rail transit with power provided by a third rail and not overhead) provides the benefit of avoiding car traffic and intersections to deliver people faster and more reliably to their destinations than bus or light rail (overhead powered), which are stuck in traffic when not in a dedicated lane. But if platooning e-buses run in the same dedicated rights-of-way as rail, they can travel just as quickly and reliably.

- Transit-oriented development: it’s unfortunately become controversial in California to try to house more people near major transit stops (nearby homeowners and their NIMBY allies don’t like it), but rail can help stimulate real estate investment to encourage the thriving, walkable neighborhoods that California needs to reduce overall driving miles and address its housing shortage. Fixed rights-of-way for platooning e-buses would provide the same market signal to developers.

Meanwhile, the e-bus platoons could provide potentially significant additional benefits over rail:

- Serious cost savings: with e-buses, transit agencies don’t need to lay tracks or have overhead or down-below wiring to power trains. They don’t need substations along the way. The e-buses would be battery powered (as they already are, through companies like BYD and Proterra), so they could recharge in central, convenient places. Yes, that process requires new charging infrastructure and software to manage it. But it’s much less expensive than hardwiring an entire rail route — and then maintaining that wiring over time. The self-driving feature also means reduced operating costs.

- Faster build times: transit agencies could build e-bus dedicated lines much more quickly without all the wiring infrastructure and tracks required of rail transit. Construction of tunnels and overpasses still take time, but transit agencies would basically just need to put down pavement and striping. Already, bus rapid transit lines can be built in about a fifth of the time as rail (and at a fifth of the cost), meaning a city can get a lot more transit, a lot more quickly, with the platooning e-bus option.

- Operational flexibility: the platooning e-buses would be free to travel on surface streets as needed in off-peak hours, giving transit agencies more flexibility to move buses around to meet demand from low-density areas outside of the right-of-way during hours with less ridership on the main line.

To be sure, there are potential downsides. First, there is some technological uncertainty, as platooning is still being tested. Second is the cost and range of batteries for buses, though electric buses are already becoming widely deployed, battery prices are falling dramatically, and energy density is improving. The e-buses also offer significant and offsetting savings on operations and maintenance based on the cheaper fuel they need and the fewer parts they have to replace. A third concerns is that more charging infrastructure for the e-buses would be needed, but that infrastructure is often simpler to install than overhead power lines or third rails.

Finally, transit advocates would need to emphasize that the prospect of platooning e-buses should not be used as an excuse to kill or postpone new rail transit proposals in the works today. Urban residents still need the infrastructure that goes with a separate right-of-way for rail, even if the technology ultimately changes. They need tunnels, grade separation, elevated lines, dedicated lanes, and overpasses and underpasses to keep rail out of street traffic. Even if platooning e-buses become widespread soon, that dedicated right-of-way construction will still be put to good use, albeit with ripped out tracks and overhead lines.

But as transit agencies think about other types of rail upgrade projects, like converting the Orange Line bus rapid transit in the San Fernando Valley in Los Angeles into light rail, maybe they should pause and assess the state of platooning e-bus technology. That Orange Line project in particular is costly, and the dedicated right-of-way already exists to convert to electric buses. If rail construction is underway in 2020 or 2021 just as platooning e-buses become market-proven, it will be a waste of money.

I look forward to discussing this issue and more with LA Metro CEO Washington on July 24th at UCLA Law. Tickets are still available for those interested in attending. Ultimately, even for those who will always love steel wheels on rail, it’s hard not to see the appeal of what new clean technology might do to expand and improve transit across the globe.

Building anything in California near transit stops is hard enough, but many affordable housing advocates argue that we should only build subsidized homes for low-income residents — and not market-rate homes for higher-income people. They cite evidence that low-income people are much more likely to actually ride the transit where they’ll live, as opposed to high-income people who will still drive.

It’s true that we should build as much affordable housing (and offices) near transit as we can to boost ridership. But we should also allow market-rate development near transit, too, for similar environmental reasons.

Yes, high-income people near transit probably won’t actually use the transit that much. But they will on balance drive significantly fewer miles than if they lived in sprawl areas. And fewer driving miles means less pollution and fewer greenhouse gas emissions.

Ironically, the evidence for this environmental benefit comes from a study meant to document how important it is for low-income residents to live near transit. The nonprofits TransForm and California Housing Partnership Corporation released a study [PDF] in May 2014, based on Caltrans’ California Household Travel Survey (CHTS), arguing explicitly for affordable housing near transit. In fact, they used the data to argue against locating higher-income housing near transit, pointing out that higher-income households drive more than twice as many miles and own more than twice as many vehicles as low-income households living within 1/4 mile of frequent transit.

But the data actually revealed something more important: higher-income residents near transit drove almost 30 miles fewer per day than similarly situated people in sprawl areas. By comparison, low-income residents only drove about 20 miles fewer per day, compared to similar income sprawl residents. Check out this chart that summarizes those results:

So while I agree we want to locate low-income residents near transit, we also need high-income people living in cities near transit. Otherwise, the increased driving miles will mean more traffic, pollution and unattainable climate goals.

As other developed countries race ahead to build high speed rail networks, the U.S. is lagging painfully behind. The result here is now sprawling cities, crushing traffic, significant air pollution, and increased transportation expenses for Americans. But why are the outcomes so different in the U.S. than in the rest of the world?

CNBC produced an in-depth report (video above) to examine some of the reasons, based on interviews with me and UC Berkeley colleague and transportation scholar Robert Cervero, among others. The piece contains some classic 1950s corporate advertisements extolling the virtues of freeways and buses and some good coverage of the various lobbies keeping our infrastructure auto-dependent.

My only quibble is that the piece repeats the false notion that city rail networks in the U.S. were systematically dismantled as a conspiracy by auto interests. The actual picture, as I detail in my book Railtown on the history of the Los Angeles Metro Rail, is much more complicated than that: it points to voter disillusionment with rail networks, coupled with rapid consumer adoption of (and preference for) private automobiles back in those early days, as the main culprit.

Still, the report does a good job presenting the difficulties funding and building high speed rail in the U.S., and it ably describes what would need to happen if the U.S. were to commit to joining the rest of the developed world by building a first-class high speed rail network.

As transit ridership falls nationwide, many system operators are struggling to redesign their bus networks to be more responsive to where people actually want to go and when. And now they can use those pocket-sized surveillance devices known as smart phones to assist them.

Adam Rogers in Wired reported on a data-fueled effort at LA Metro to track transit riders via their cell phone data:

Cambridge Systematics, a transportation consultancy, acquired the kind of location information your phone continuously produces—from every app you didn’t say “no” to. The data was “hashed” so that researchers could connect geolocations (at a resolution of about 300 meters) to a device but couldn’t link the device to a phone number or a number to a person. Even with the resolution blurred this way, you can still discern a picture.

They found that commute times are still true, with two peaks between 7 and 9am and another between 3 and 6pm. No big surprise there. But they also found a third peak, from mid-day to about 9pm, as people run errands and see friends. The trouble is that this third peak coincides with a time period when traditional transit slacks off.

Furthermore, people are traveling outside of areas with the greatest population density and at shorter distances, contrary to how long-distance commuter transit lines are designed. Specifically, the cell phone data showed that “only 16 percent of trips in LA County were longer than 10 miles. Two-thirds of all travel was less than five miles. Short hops, not long hauls, rule the roads.”

The agency surmises that faster, more frequent bus service on these specific, well-traveled routes could potentially net more riders:

[The] team ran billions of cell phone-registered trips through the agency’s regional planner to estimate how long they would take on the transit system. Then they ran the same trips through Google Maps to see how long they’d take to drive. Some 85 percent of trips could be taken on mass transit, but fewer than half were as fast as driving. … But laying the fare card data alongside the larger set of phone logs showed that even if a trip took about the same amount of time, just 13 percent of travel on that route was by transit.

Clearly a bus system redesign based on where people want to go and when, and relying on faster service, will be crucial for success. But speeding up the buses (and making them more appealing than passenger vehicle trips) will require a change in land use priorities. That means more bus-only lanes and less publicly mandated and subsidized parking for private vehicles. And it also means congestion pricing to reduce traffic and provide revenue for transit alternatives.

While privacy advocates may have concerns about the methodology used in this effort, at least LA Metro now finally has a more accurate window into traveler preferences across the region. But we’ll likely need larger political changes to fully address the problem.

Yesterday was a big day for SB 50 (Wiener), the bill to upzone residential areas near transit and jobs. The bill faced a potentially hostile Senate Governance and Finance Committee, chaired by State Senator Mike McGuire from Sonoma County and author of the rival Senate Bill 4. Despite the treacherous path, the outcome was a decisive win with only one vote against (Sen. Hertzberg of Los Angeles), albeit with significant amendments to the bill.

The new bill language has not been released, but based on the committee discussion and follow-up statements from Sen. Wiener and his office, the amendments essentially appear to do two big things (among other changes):

- Exempt SB 50 from counties with populations less than 600,000, except for cities within those counties with populations over 50,000 that have rail or ferry stops (see the green/purple parts of the flow chart below)

- Legalize “by right” permitting of single-family homes into duplexes, triplexes, and fourplexes across the state, albeit with only minimal demolition of existing structures allowed.

The amendments now make the overall bill relatively complex, but Berkeley-based artist Alfred Twu drew up this handy flow chart to explain how the bill will now work:

For a graphic on the counties now affected, here is a map from Barak Gila with the counties over 600,000 population (in which SB 50 applies) in yellow:

So did Marin County get a carve out, in a deal to merge the bill with county representative McGuire’s SB 4? Notable cities now apparently exempted from SB 50 include the SMART train and ferry stop in Larkspur and the ferry-stop towns of Sausalito and Tiburon. Yet San Rafael and Novato (two SMART train stops) are still covered by SB 50.

What about Sonoma County? Cities with SMART trains that no longer would be under SB 50 jurisdiction include Cotati, Rohnert Park, Cloverdale, Healdsburg, and Windsor. Still included are Petaluma and Santa Rosa.

In Southern California, Santa Barbara County’s Goleta and Carpinteria Amtrak stations also would not be covered by SB 50, while the City of Santa Barbara would still be affected.

Meanwhile, notable other cities with rail or ferry stops within those non-yellow counties, to which SB 50 will still apply, include Vallejo, Fairfield, Vacaville, Roseville, Rocklin, Madera, Modesto, Merced, Davis, Chico, Redding, and Salinas. And of course the remaining yellow counties represent major population and employment centers that could greatly increase housing production with SB 50 upzoning.

On balance, this new population criteria is not a bad compromise, as it means most of the core areas of California that prevent new housing are still affected. But the SMART train line is pretty well decimated by this compromise, as is the Santa Barbara Amtrak line. It’s a relatively small but painful price to pay, given the potential benefits statewide with the remaining areas.

Meanwhile, the fourplex by-right provision could potentially open up significant densification in California everywhere, a la the recent Minneapolis plan to end single-family zoning and allow triplexes city-wide. But could this new SB 50 provision encourage more high-density sprawl, with fourplexes in outlying areas that don’t have access to transit and therefore lead to more traffic and pollution? The original beauty of SB 50 (and its predecessor SB 827) was that it targeted transit neighborhoods to reduce overall driving miles. The fourplex provision could undermine those environmental benefits. Yet since the fourplexes (or other smaller divisions) can only involve minor demolition of existing structures (or building from the ground up on vacant parcels), the deployment may not be as sweeping as it might initially appear.

Overall, SB 50 cleared a major hurdle yesterday before its eventual advancement to the Senate floor, emerging relatively unscathed and with some potentially major new additions. If it passes that chamber, it will be on to the Assembly, with further carve-outs and compromises likely.

What’s the latest with California’s major proposed legislation to remove local restrictions on new housing near transit and jobs? I wrote back in December about Senate Bill 50 (Wiener), which would relax local requirements on density, parking, floor-area ratio and height (in some cases), for projects near transit and in high income “job-rich” communities that lack commensurate housing (read: Cupertino, home of Apple).

SB 50 also contains provisions to protect low-income renters from eviction from any new development under the bill and takes off the table (at least for the near future) large swaths of urban low-income areas deemed to be “sensitive communities.” For a visualization of what that means on the ground, see p. 11 (figure 5) of the CASA compact for a map of San Francisco Bay Area zones that would be exempted under this provision.

So how is the bill doing? Notably, SB 50 sailed through its first committee hearing last week with overwhelming approval. But it may face critical obstacles in its next hearing at the State Senate Governance and Finance Committee. That’s because that committee is chaired by State Senator Mike McGuire from Sonoma County, who authored a rival bill (Senate Bill 4) which would do much the same to relax local zoning near transit as SB 50, except with the big difference that it would exempt any “city with a population of 50,000 or greater that is located in a county with a population of less than 1,000,000” (which would exempt McGuire’s hometown of Healdsburg from the bill’s provision).

So the politics remain dicey going forward. The difference this year though is that Wiener has lined up powerful political support from organized labor, who like the job opportunities that would flow from more housing projects in urban areas. And by exempting in the near term “sensitive communities” with low-income tenants, Wiener has largely neutralized (for now) opposition from tenant groups who helped sink last year’s version, SB 827.

As a result, the opposition has so far been revealed as wealthy communities up and down California, who are resistant to allowing any new development or letting newcomers move in who can’t afford an expensive single-family home. They frequently use lines of attack like the bill is a “developer giveaway” or that proponents are “real estate shills.”

To counter these voices and win more support from advocates for low-income renters, Wiener has introduced amendments that tighten up the affordable housing requirements for any project that uses the bill’s provisions. Specifically, SB 50 now has ‘inclusionary zoning’ requirements in which developers with projects with between 20-200 units must make 15% of the units affordable to low-income residents (implemented on a sliding scale, with fewer units required if they’re available to extremely low-income residents), while 200-350-unit projects must provide 17% affordable units. Any project above 350 units must have 25% affordable units (also on a sliding scale depending on the income eligibility). Housing projects under 10 units are meanwhile exempt from providing any on-site affordable units, while projects of 10-20 units in size can pay in-lieu fees. With these provisions in place, the bill would likely lead to a significant deployment of subsidized affordable units to accompany new market-rate development.

But what practical effect will SB 50 likely have on the ground, assuming it can survive the messy politics and become law relatively intact? UC Berkeley’s Terner Center for Housing Innovation and Urban Displacement Project conducted an interesting case study policy brief and found that any likely boost to new housing under SB 50 would mostly be small scale and in high-income communities, though that impact varies depending on whether other local restrictions are in place.

The UC Berkeley study involved a parcel and financial feasibility analysis on four representative neighborhoods in the state, with the following highlights:

- Developers will get a much higher return on SB 50 projects in upscale areas, even with the higher land costs, meaning that most projects will be built in these areas and not in low-income areas (as I argued back during the SB 827 debates last year).

- Most of the available parcels (at least in these four study areas) are too small to support big projects, meaning most development will likely be of the 12-unit or less variety; in addition, the bill’s restrictions on developing properties with tenants will likely take a significant number of parcels off the table (a good thing, from the point of view of protecting current tenants from eviction).

- High on-site affordable housing requirements (discussed above) will be financially feasible in upscale areas but could sink projects in lower-income neighborhoods that otherwise barely pencil, so Sen. Wiener may want to consider a less rigid approach to the affordable housing requirements and instead scale them based on the value of the project.

- Remaining local government restrictions, such as high setback requirements and bans on projects that cast too much shadow (which was a dealbreaker for an important housing project in San Francisco that the board of supervisors just killed because it would cast occasional shadows at an adjacent park), will still impede projects, even if SB 50 passes.

- Developers may choose to ignore the benefits of SB 50 if a local government has already made it easy to permit projects at the current, locally determined height and density limits, just to avoid a protracted permitting fight that would come with using new, state-allowed higher limits.

The findings from this study should be clarifying for the SB 50 debate going forward. First, they show the relatively limited impact that SB 50 might have on the ground, at least compared to some of the hyperbolic rhetoric and initial studies about the predecessor bill’s impact in specific areas.

Second, SB 50 will likely end up being a just step (albeit a big one) in the right direction on boosting housing supply to match demand. Further reforms (some under consideration in other bills being debated this session) will need to focus on streamlining the permitting process for projects consistent with this new zoning. Otherwise, local governments are likely to respond to SB 50’s passage by adding more steps to the permitting process in order to kill projects through delay and multiple veto points. State legislation may also need to address the other zoning restrictions on new development that SB 50 leaves untouched, such as the aforementioned setback and shadow limits.

California’s current housing shortage certainly didn’t happen by accident — it’s the result of a complicated web of politics that SB 50 and its backers are trying to undo, piece by piece. We’ll have to stay tuned as more studies assess the bill’s impact and Wiener entertains more political compromises to win over support.