2016 could be a big election year for local transit tax measures in California. The Silicon Valley Leadership Group is trying to rally and coordinate ballot measures in multiple Bay Area counties, including Santa Clara, San Mateo, Santa Cruz, San Francisco and Contra Costa.

2016 could be a big election year for local transit tax measures in California. The Silicon Valley Leadership Group is trying to rally and coordinate ballot measures in multiple Bay Area counties, including Santa Clara, San Mateo, Santa Cruz, San Francisco and Contra Costa.

Backers hope the measure could lead to regional improvements and address the $59 billion transportation infrastructure shortfall. Plus, the measures could fund traffic-busting alternatives like transit and walking and biking infrastructure.

But Jon Coupal of the Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Association begs to differ:

“California is already a high-tax state,” said Jon Coupal, president of the Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Association, an anti-tax group, adding that low-tax states like Texas and Florida do not suffer similar traffic problems.

He suggested California Governor Jerry Brown abandon the state’s “foolish” high-speed rail project and instead expand existing freeways with the money, a portion of which is raised from polluters complying with the state’s cap-and-trade program.

“There’s nothing more polluting than a freeway full of parked cars that are idled,” he said, explaining why he does not think the money should go toward building the state’s first bullet train.

Coupal evidently doesn’t know that Florida and Texas actually have really bad traffic. Miami ranks fifth-worst nationwide (worse than the Bay Area in eighth place), according to the 2012 Texas Transportation Institute report [PDF]. Meanwhile, Houston ranks ninth and Dallas isn’t far behind.

Coupal also doesn’t acknowledge that these “low-tax” states also have notoriously weak restrictions on land use development, meaning housing is cheaper because there’s more of it. If Coupal and his group really wanted to help California businesses, he would help the state overcome local land use policies in our metropolitan regions that have artificially restricted supply, inflated prices and rents, and driven development to the fringes, paving over open space and leading to polluting, crushing traffic.

Of course, his organization’s Prop 13 from 1978, which slashed property tax rates, hasn’t helped the situation. It disincentivizes local governments from approving new housing over retail in order to chase sales tax dollars, and it discourages longtime urban property owners from improving or developing their buildings, given their low property tax obligations.

Meanwhile, his attack on high speed rail is baseless. The rail system will expand capacity in the San Joaquin Valley along Highway 99. So how exactly would Coupal propose widening Highway 99, given that it travels through multiple densely built environments, including cities like Fresno and Bakersfield? There’s simply no more room in most parts of the corridor for expansion.

Bottom line: California needs to think outside the 1950s when it comes to moving people. More and bigger highways hasn’t worked so far. No wonder Bay Area county leaders are optimistic that voters will agree come next November.

It was 25 years ago (yesterday) that the Blue Line opened from downtown L.A. to Long Beach, ushering in a modern rail transit era in Los Angeles. Laura Nelson of the Los Angeles Times ran a nice piece on the occasion, including a few quotes from yours truly:

It was 25 years ago (yesterday) that the Blue Line opened from downtown L.A. to Long Beach, ushering in a modern rail transit era in Los Angeles. Laura Nelson of the Los Angeles Times ran a nice piece on the occasion, including a few quotes from yours truly:

As Southern California prepared to welcome the region’s first light-rail line since the demise of the red Pacific Electric streetcars a generation before, reviews on rail were decidedly mixed.

“There is just no reason for optimism,” one academic told The Times in 1985, adding that the line linking Los Angeles and Long Beach would be “a ghost train.” Five years later, an MIT researcher warned that “the blind cult of the train could be as dangerous and destructive as the unthinking worship of the freeway.”

Instead, the Blue Line, which turns 25 this week, eclipsed ridership benchmarks to become one of the most heavily traveled light-rail lines in the United States. Its debut also marked the dawn of an ambitious era of rail expansion in Los Angeles County: Since 1990, officials have built five more rail lines and 65 more miles of tracks, with 37 more planned during the next two decades.

Always nice to prove naysayers wrong, although the line — and the neighborhoods around the stations in particular — still needs a lot of work.

Move LA produced this new video from their recent Union Station conference, featuring many top elected officials and community leaders:

ULI, the national nonprofit of real estate professionals and others interested in downtown development, reviewed my book Railtown to find out just what is going on with rail in Los Angeles:

ULI, the national nonprofit of real estate professionals and others interested in downtown development, reviewed my book Railtown to find out just what is going on with rail in Los Angeles:

Railtown chronicles the latest chapter in the Los Angeles saga—the city’s transition from a smoggy, car-loving, freeway-dominated megacity to an emerging cluster of walkable urban centers linked by public transit, including light and heavy rail as well as buses. This saga resembles a Greek tragedy. The central figure’s fatal flaw—the political geography of metropolitan Los Angeles and the inability to agree on a plan—drives the narrative while optimistic local leaders who view rail as the solution to the region’s traffic and environmental problems struggle to convince politicians, 88 self-centered cities, and the county electorate to accept yet another reinvention.

The review is not all positive, as the reviewer seems to have challenges with what he calls a “dense” read, but he says “for those wanting to understand the details of Metro Rail’s checkered history, this is the book to read.”

It’s huge news for the Maryland suburbs of Washington DC. The Purple Line is a light rail connector filling in the spokes of the heavy-rail Metro system and connecting two major dense suburban centers. The project was suddenly in doubt when Larry Hogan was elected governor last November, a surprise win for a conservative in an overwhelmingly liberal state. Hogan had campaigned against the wasteful spending of the project and has made more money for automobile infrastructure a priority.

It’s huge news for the Maryland suburbs of Washington DC. The Purple Line is a light rail connector filling in the spokes of the heavy-rail Metro system and connecting two major dense suburban centers. The project was suddenly in doubt when Larry Hogan was elected governor last November, a surprise win for a conservative in an overwhelmingly liberal state. Hogan had campaigned against the wasteful spending of the project and has made more money for automobile infrastructure a priority.

But Hogan’s transportation secretary came out in favor of the project, and the federal transit agency had already pledged support. The governor is still flashing his conservative bona fides by requiring cost cutting on the project and more county contributions. He also wants the private contractors who build it to step up with financial support. Overall, those positions could be very helpful for the economics of the project.

Here’s more detail:

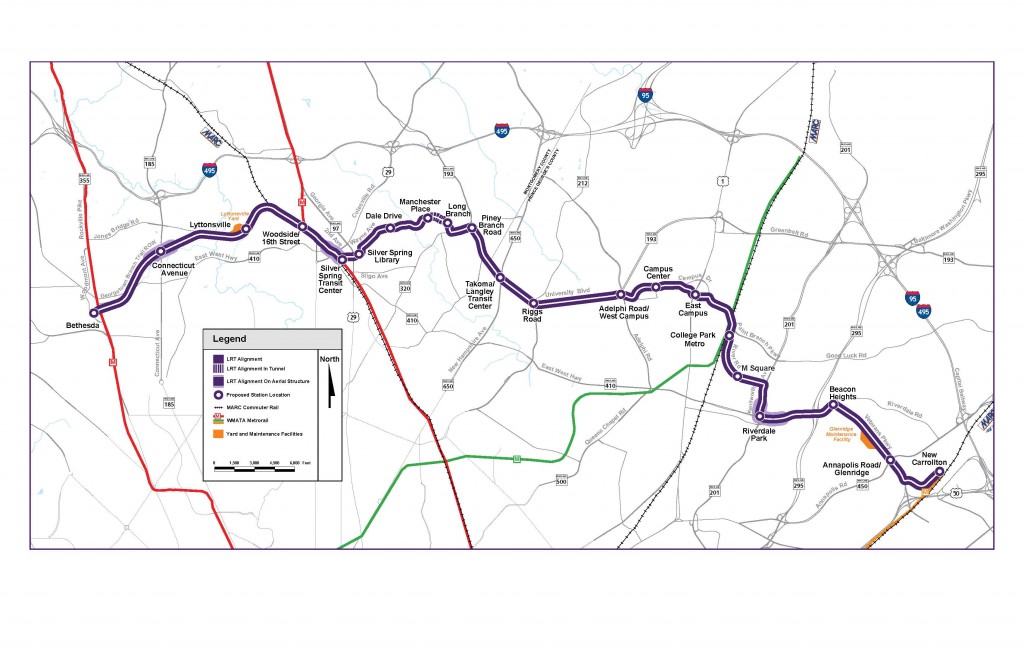

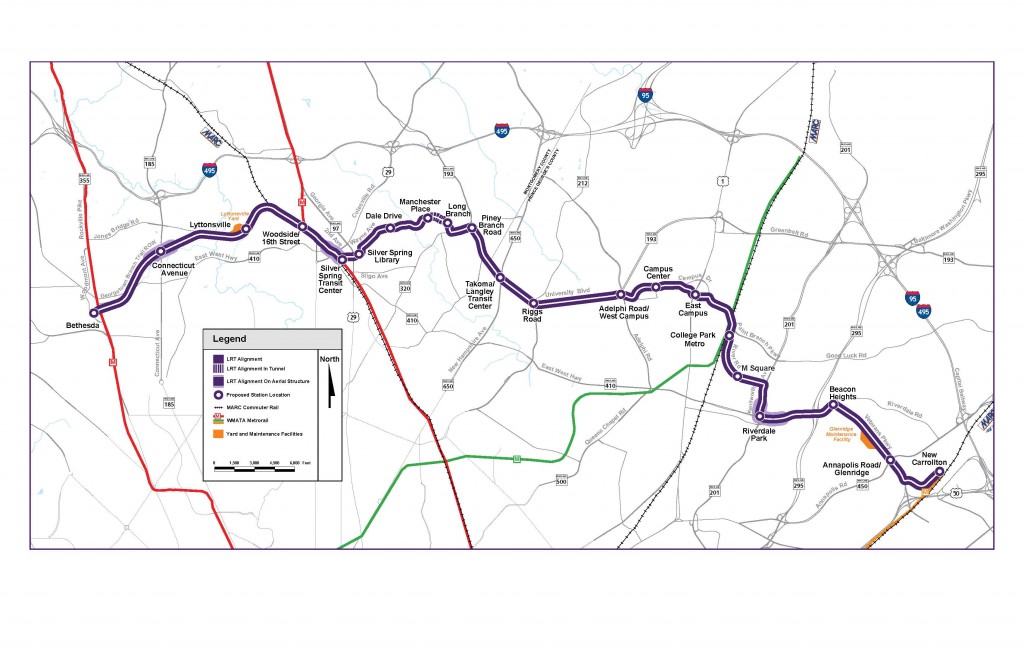

The line would still have 21 stations and run from Bethesda in Montgomery to New Carrollton in Prince George’s. It would pass through Silver Spring and the University of Maryland’s College Park campus. The Purple Line will connect to Amtrak and MARC commuter rail stations and will be the first rail line to directly connect spokes of a Metrorail system designed decades ago to carry commuters between the suburbs and downtown Washington.

Hogan also was influenced by Washington-area politicians and business leaders, who said the project was crucial to improving transit and encouraging growth inside the Beltway.

“The Purple Line is a long-term investment that will be an important economic driver for Maryland,” Hogan said. After expressing skepticism in the past about what he saw as overblown forecasts of how many jobs the project would create, he said construction alone would create 23,000 jobs in Maryland over the next six years.

And hey, I’m not claiming credit, but Tuesday night I give a presentation for Washington DC Purple Line advocates on LA’s Metro Rail history, and on Thursday the conservative new governor approves the line. You make the call.

For anyone in the Washington DC area, I’ll be speaking tonight at 7:30pm at the Rockville Public Library about the history of Los Angeles Metro Rail, as detailed in my 2014 book Railtown.

Washington DC rail advocates have been fighting their own battle recently over the proposed Purple Line, a light rail connector between two horseshoe ends of the heavy rail Red Line in the upscale Maryland suburbs of Washington DC (map below). The project was set to go until Maryland voters elected Republican Larry Hogan governor last November. Hogan is threatening to kill the project if costs don’t come down.

Local backers of the Purple Line, Act for Transit, are sponsoring the talk tonight. Hopefully the history of rail battles in Los Angeles will be instructive for advocates in Washington DC.

In the second part of my interview with Santa Monica Next, I come out swinging against communities that refuse to allow development around rail transit stations (you can read part one here). The prompt was when Santa Monica homeowners rose up last year against a badly needed infill project around the future Expo Line station:

This is not just a Santa Monica problem. You see it in the Bay Area, San Diego, Sacramento. If they aren’t going to do their part to help out with the region’s housing needs and economic challenges, if a community is not willing to allow a development around rail transit networks that the whole region pays for, then I feel they shouldn’t have access to these multibillion dollar investments.

It’s a drag on taxpayers to have to pay for underperforming rail lines. It’s a drag when you don’t have enough riders, and what generates riders are the jobs and housing around the transit stations. If locals don’t allow the jobs and housing to come in, then they are basically telling everyone else to pay for their small group of residents and commuters to have access to a fancy rail line. And, yet, they aren’t willing to make the changes necessary to make the rail line a cost effective investment.

California transit leaders should consider taking this step. The model is in the San Francisco Bay Area, where Metropolitan Transportation Commission leaders adopted a policy to condition future transit spending on local governments planning for station area development. We’re long overdue for the rest of the state following suit.

If a community like Santa Monica refuses to grow around rail transit, then the region should refuse to subsidize their exclusive access to that transit.

Zocalo really covered it all with me for a Q&A before my talk on rail last November in Los Angeles. Most relevant for an environmental blog:

Q: What’s the quickest way to dispel climate change deniers?

A: I usually talk about all the positive things, and try to shift the debate away from science—energy independence, the fun of driving an electric vehicle, the fun of kissing your gas station goodbye, more local jobs. I try to go to the positives that we would get in our society if we could switch out of dirty fuels. It’s more disarming the deniers rather than getting in a debate. My basic philosophy is you can never convince anyone of anything.

Since I confessed in the interview to having a Richard Nixon impersonation, this might be a good time to list my top three favorite Nixon quotes:

“You won’t have Nixon to kick around anymore, because, gentlemen, this is my last press conference.”

“People have got to know whether or not their president is a crook. Well, I’m not a crook. I earned everything I’ve got.”

“When the President does it, that means that it’s not illegal.”

My wife just visited the Nixon Library in Orange County for a research project, and she told me the place has giant Nixon quotes on the wall. None could be as good as these three.

Ryan Reft at KCET looks at the history of the Bus Riders Union and the Los Angeles Metro, and how race and class issues have affected bus and rail transit:

Ryan Reft at KCET looks at the history of the Bus Riders Union and the Los Angeles Metro, and how race and class issues have affected bus and rail transit:

In 1992, the Labor/Community Strategy Center (LCSC), under the leadership of Eric Mann and Manuel Criollo, formed the Bus Rider’s Union, a project aimed at drawing attention to the class and racial inequality at the heart of MTA transit policy. Both Mann and Criollo came to realize the impact of these inequities through their work fighting environmental racism for LCSC. While trying to organize residents in and around Los Angeles County they kept encountering the same issue: their constituents worried about local oil refineries and air pollution, but what impacted even more directly was their two to three hour commutes to work from places like Wilmington to the Valley or Los Angeles. “That was a transformative moment for us,” reflected Criollo years later. “The buses would have forty people sitting and forty people standing, no air conditioning, completely messed up … And on Metrolink, people were riding like Disneyland.”

The litigation risk for Metro’s rail transit program has faded since the 1990s, due to an intervening Supreme Court case that makes suing over discrimination harder. But the moral and economic case for prioritizing low-income transit riders remains. One easy step for Metro to address these challenges would be to lower bus fares. It’s a great way to boost ridership and help the people who truly need it.

Even without litigation, the racial and class dynamics will continue to affect Metro decision-making, particularly as economic inequality persists and worsens.

In the wake of the Philadelphia Amtrak crash, my Zocalo co-panelist Tom Zoellner pens a Washington Post op-ed bemoaning the sorry state of Amtrak, due to federal policy:

So don’t blame Amtrak for the mess. Blame history and the law. If Americans really want anything more from their passenger trains besides a future of lumbering banality — besmirched by a few dozen derailments and a handful of passengers killed each year — the 1970 law must be amended to guarantee a healthy level of federal support, clearly prioritize passenger trains over freights, take posturing by Congress out of the equation, double-down on advertising and capturing new customers and lay down dedicated tracks outside the Northeast Corridor. The current Passenger Rail Reform and Investment Act of 2015 doles out what amounts to more starvation rations: a paltry $7 billion over the next four years, which means nothing is going to change. Amtrak needs to stop becoming a symbol of American incompetence and start leading the way in an era of fuel shortages and highway congestion.

He compares rail in the United States to rail in Europe:

Americans who vacation in Europe are frequently struck by the professionalism, convenience and reach of the continent’s rail network and ask a very good question: Why can’t we do that here? How can a nation whose industrial power was built by the railroads be left with a starving system that might embarrass former Soviet bloc countries?

The one big difference Tom doesn’t note though is that European cities are much closer together than many U.S. cities, outside of the northeast corridor of course. Given the vast size of this country, passenger rail has a hard time competing with airplanes for many trips. Rail is best suited to cities that are too close to fly but too far away to drive conveniently.

But Tom’s larger point is correct: you get what you pay for. And in the case of Amtrak, regardless of the cause of this accident, prioritizing freight over passengers and starving the train budget means we’re not getting enough.