In the hand-wringing over the Expo Line to Santa Monica’s slow travel times, Kerry Cavanaugh of the Los Angeles Times argues that transit like Expo shouldn’t have to deal with automobile traffic:

The long-term answer, however, is grade separation. Trains can run faster and more safely and stay on schedule if they don’t have to cross paths with drivers, pedestrians and cyclists. (KPCC-FM (89.3) analyzed Metro data and found that, no surprise, the underground subway lines have the fewest delays.)

Of course, it’s more expensive to build grade-separated rail or to retrofit an existing system. An overpass can cost as much as $20 million, one official estimated. But as L.A.’s rail system expands in an increasingly dense, traffic-clogged urban area, it’s penny-wise and pound-foolish to build lines that have to stop at red lights and share the road with cars.

She rightly points out that these trains should also have signal priority to avoid getting stuck at red lights.

It’s obviously a better deal to have grade separation in terms of reduced travel times — and it’s much safer for pedestrians and other drivers as well, not to mention for the transit riders in the train cars that get hit.

But the problem with grade separation, as Cavanaugh acknowledges, is that it’s very expensive to build lines that run above or below street level. And retrofitting the newly opened Expo Line to either trench the line through downtown Los Angeles or go aerial is essentially infeasible at this point. First, it would cost money that Metro doesn’t have. And second, it would require essentially mothballing the existing train line in whole or in part for a few years during construction.

But the problem with grade separation, as Cavanaugh acknowledges, is that it’s very expensive to build lines that run above or below street level. And retrofitting the newly opened Expo Line to either trench the line through downtown Los Angeles or go aerial is essentially infeasible at this point. First, it would cost money that Metro doesn’t have. And second, it would require essentially mothballing the existing train line in whole or in part for a few years during construction.

This same challenge is evident in the calls to convert the Orange Line busway in the San Fernando Valley to light rail. If the construction upgrade happens, the busway will be out of service, causing a major headache for transit riders.

The best solution is to simply build the best line from the start. And given that transit funds are scarce in a region as big as Los Angeles, that means focusing on low-cost solutions like signal priority and the ability to close down under-performing stations to speed up travel for everyone else, or double-tracking parts of the line to allow express trains to pass slower ones (which may be cheaper overall than grade separation).

Demanding grade separation in new projects is a good idea, but even then transit advocates will likely have to compromise it away in the name of fiscal responsibility. So they should think through low-cost but effective backup plans early on to ensure speedy and reliable service.

Sunbelt cities across America are investing in rail and transforming themselves from car-dominated regions to urban railtowns. I cover the story in Los Angeles extensively in Railtown, but the same trends are evident in cities like Charlotte, Denver, and Phoenix.

Yesterday I spoke about this phenomena with host Dan Loney on SiriusXM radio’s Knowledge@Wharton, a business-themed program out of the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania. You can listen here to the first five-minutes of the segment, which otherwise ran for 30 minutes:

If you have a SiriusXM subscription, the full show is available via the “On Demand” feature for the next seven days, on channel 111. And if you don’t have a subscription, you can start a 30-day free trial here.

The groundbreaking ceremony for the just-opened Expo Line light rail to Santa Monica took place back on September 29, 2006. I was there and got this cool mini shovel memorabilia to honor the occasion:

That means that the opening of the full line to Santa Monica on Friday happened just under 10 years after groundbreaking. For those keeping score at home, that means the Expo Line Construction Authority managed to build 1.5 miles of rail each year.

As far as rail lines go, this should not have been a very complicated construction job. The line runs virtually entirely at-grade, with minimal trenching and a handfull of overpasses. In addition, the right-of-way already existed and therefore required relatively little property acquisition and condemnation.

In short, the amount of time spent to build this line seems absurd. That’s not even counting the years of planning. And yet the region’s leaders apparently aren’t upset by it or demand any better.

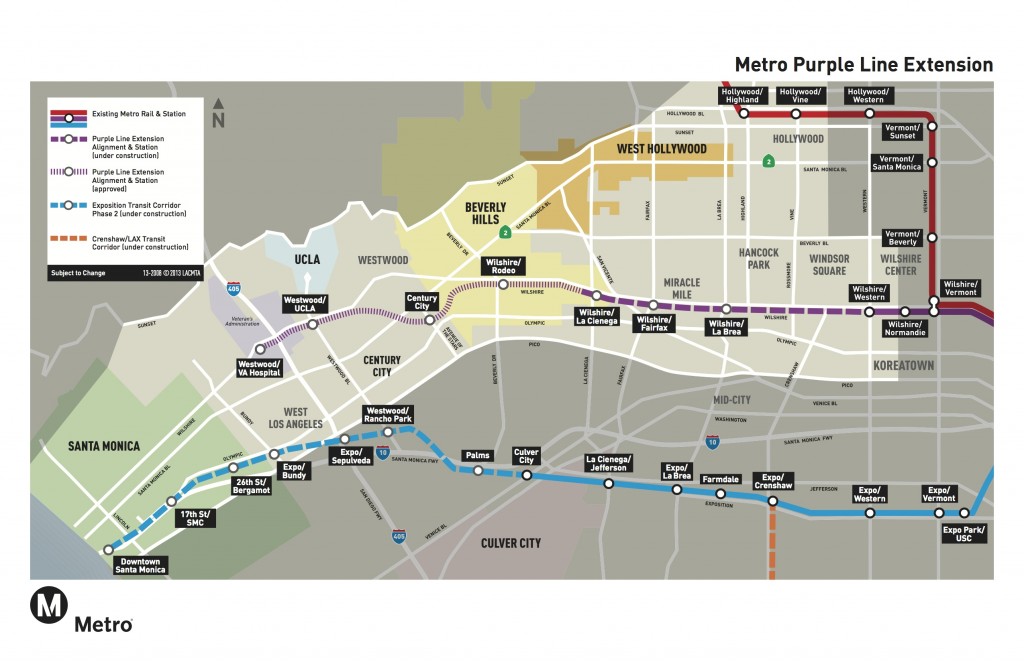

Sadly, at this point, Californians have just gotten used to these interminable construction timetables. High speed rail is way behind schedule and won’t open until probably the 2040s or 2050s, if at all. The Purple Line subway extension down Wilshire most likely won’t be operational until the 2030s. Even automobile projects like the San Francisco Bay Bridge eastern span took over a decade to open.

It’s a subject I tackled for UCLA Law in 2014, with the report Back in the Fast Lane, and an op-ed in the San Francisco Chronicle. Yet I’ve seen little interest among policy makers (or even the public) to tackle this issue. Why the complacency?

For those who care about boosting transit, they have an interest in getting ahead of this problem. A few bad headlines can undermine political support for transit investments, especially in California where advocates need two-thirds voter approval for tax measures. And it also means we’re getting much less bang for our buck on these projects, which means fewer projects that benefit people.

It’s enough to make me mad. Or maybe it will later. At some point anyway.

For yesterday’s celebrations around the unveiling of the Expo light rail line to Santa Monica from downtown L.A., I had an opportunity to do an extended interview on the politics of the line with KCRW’s Saul Gonzalez. You can listen to the audio here.

Time to fill in the dotted blue dots on the Expo Line map above to Santa Monica: as of today at noon, they’ll be solid blue as the route becomes operational.

Time to fill in the dotted blue dots on the Expo Line map above to Santa Monica: as of today at noon, they’ll be solid blue as the route becomes operational.

So what’s next? Here’s what I’ll be looking for in the months (and years) to come:

- Long travel times: will people be frustrated by the nearly hour end-to-end ride from downtown Santa Monica to downtown L.A.? Current time projections are 50 minutes, which is a long time for a ride that can take 15 minutes by car with no traffic. The LA Weekly and Los Angeles Times have done a good job of flagging this issue. There are no easy solutions, but at a minimum the City of L.A.’s transportation department should give the trains signal priority so they don’t stop at red lights downtown. Meanwhile, Metro should consider skipping under-performing stations, at least temporarily.

- Collisions: with the train running most at-grade (i.e. street level) and going through some funky intersections from the old railroad right-of-way, will the line experience a lot of accidents like the similarly situated Blue Line, one of the deadliest in the country? And what will the political response be? Easy solutions would be more crossing gates to block traffic, including for those driving in the wrong lane who try to get around single-lane crossing gates (it happens).

- The Expo bike lane: part of the rail extension includes a badly needed dedicated bike path. There’s a gap in the route though, apparently due to neighborhood opposition (what’s new). But the conditions are ripe to make this path even more successful, on a per traveler cost basis, than possibly the rail line next to it. The route is largely flat, the weather is great, and biking is super convenient. So this may be the unsung hero in the whole project.

-

Transit-oriented development along the route: the whole point of rail lines is really about economic development and land use, as Politico covered in an excellent profile on Denver’s burgeoning rail network. Right now, the route covers a lot of relatively low-density areas, and Santa Monica infamously shot down an office and housing project (see rendering) next to one of the new stations, resulting in a low-rise suburban office park to take its place. Will the cities along the route allow new development near the stations? If not, the line will be doomed to under-performance.

- Changing the politics of rail in Los Angeles: with rail now serving a highly visible, major job center in the region, will its existence solidify rail as a politically entrenched force? A bus activist in the Bay Area once told me that nobody would ever scale back BART in favor of buses now, because “BART is too precious.” Will the same thing happen to Metro Rail? As the system begins hauling more people and possibly taking a central role in economic development (subject to #4 above), it may lock in ongoing voter support for the foreseeable future. And not just in the westside. After all, with the eastern county Gold Lines operating, many of those residents will have a stake in accessing jobs in the western part of the county, too.

I’m sure other issues will arise as the system matures, and I’ll try to follow them on this blog. But for now, something to consider as many westside workers and residents of Los Angeles finally get their day to ride the rails.

Los Angeles is about to unveil one of the most consequential transportation projects in recent history. I don’t want to get too hyperbolic, but the coming of the Expo Line light rail transit tomorrow to Santa Monica is, as our current vice president might say, a big f***** deal.

The reason for the import is twofold: first, the location. The westside of Los Angeles County is the most densely populated in the region and the most traffic-choked. Expo, running from downtown Los Angeles all the way to the beach, will finally open that area up to the rest of the train network that’s been growing in fits and starts since 1990. That means a good ridership boost for the whole system and a major alternative to driving for many westside residents and workers.

Second, and more intangibly, the train will now serve an influential part of the population, who will finally be seeing a train in their backyard, and a highly visible location for tourists and Angelenos alike.

Second, and more intangibly, the train will now serve an influential part of the population, who will finally be seeing a train in their backyard, and a highly visible location for tourists and Angelenos alike.

Some of the most wealthy and powerful people in Los Angeles, from business to media to opinion leaders, reside in the westside. They are the ones who set much of the tone for the region in its popular discourse and are key to much of its politics and private investment, particularly during a time of tremendous income inequality. As opinion shapers, it matters if they complain about LA “not having any transit” (leaving aside the comprehensive bus network), so a train in their backyard undermines that claim.

In addition, with trains running through the streets of Santa Monica and along Interstate 10, this line will be a visible symbol of the ongoing transformation in Los Angeles’s housing patterns, transportation options, and self-image. Some of the most powerful people in the region will be seeing it firsthand, as well as the legions of tourists from around the world (and the region) who visit downtown Santa Monica and nearby areas.

Ultimately, actions and investment matter more than symbols, and the everyday county voter has certainly been the key to funding these investments. But images and impacts are mutually reinforcing, and the symbolism of Expo — as much as the ridership boost and potential for neighborhood development along the corridor — may matter just as much in the long run.

All in all, it makes tomorrow a momentous day in the history, and future, of transportation and development in Los Angeles.

With the opening of the Expo Line to Santa Monica later this week, KPCC radio is giving this momentous occasion some comprehensive coverage. Transportation reporter Meghan McCarty interviewed me and others about the significance — and potential challenges — of the line. Here is an excerpt:

Elkind said the county needs to brings more people closer to the train line.

“The best thing you can do is put affordable housing – that type of investment is really critical to create that type of thriving, compact neighborhood,” he said.

More buildings could be a tough sell on the Westside, where development is a hot button issue. Both in Santa Monica and Los Angeles, voter-led efforts to limit new buildings have drawn tens of thousands of signatures in support. Fears of increased traffic and loss of neighborhood character have driven the anti-development sentiment.

I’ll have more thoughts on both the upsides and areas of concern for the new line soon.

You can’t go too far in L.A. transit circles without hearing about the Great Streetcar Conspiracy Theory. The gist is this: L.A. had an awesome rail system a century ago (the Yellow and Red Cars), but auto interests bought it up and dismantled it.

So the terrible traffic and car-dependency in L.A. is solely the result of nefarious corporate action.

It’s a convenient but ultimately untrue tale, as I covered in my book Railtown and on this blog.

Colin Marshall over at The Guardian discusses this myth, lending some credence to it by citing a problematic grand jury proceeding that supported the conspiracy. Still, he notes the complex array of factors that led to the dismantling of the streetcars:

This [streetcar] conversion process had begun well before General Motors and the others involved in National City Lines started buying up streetcar systems. By the end of the 1920s, about 20% of the country’s cities used buses only, and even in 1923 the Pacific Electric had put their order in for buses to run instead of trains on some routes. NCL did indeed replace more trains with buses after purchasing the financially troubled Los Angeles Railway in 1945, but that just continued a process that had begun much earlier, and which took place similarly across the country and indeed the world. Streetcars vanished in almost every metropolitan area in the United States, and only in 10% of those cases did NCL have anything to do with it.

He also rightly points out that the public grew disillusioned with the streetcars and refused to bail them out, while the federal government helped subsidize suburban sprawl through infrastructure investment and tax policies.

He spoke to me for the article, concluding with this thought:

So why does the Great American Streetcar Scandal live on in the hearts and minds of Los Angeles? “Angelenos are rightfully frustrated by being forced to buy cars and sit in traffic to get around, and many feel like this situation was foisted on them without the consent of residents,” says Elkind. “It’s easy to blame car companies because they’re the logical economic beneficiary of this car-oriented system. But the reality is more complex, and if there’s any conspiracy here, it’s on the part of local officials who kept approving sprawling subdivisions that have led to the present inefficient land use patterns.”

And that land use “conspiracy” continues to this day, with far-flung subdivisions approved through California that require automobiles for mobility. And it’s metastasizing to the north of L.A. County, with Supervisor Antonovich’s pet project to connect a super-highway across the Mojave Desert.

It would make Judge Doom proud.