If you want to hear about rail in Pasadena, come out tonight. I’ll be discussing the past and future of the Gold Line light rail to Pasadena and beyond, at the Downtown Pasadena Neighborhood Association’s annual meeting at 7:00 p.m. I’ll also cover Measure M on the county ballot and what it might do for a proposed Gold Line extension beyond the current terminus in Azusa. More info here.

And if you’re a lawyer in need of some environmental law discussion (and continuing legal education credits), come out tomorrow to the Los Angeles County Bar Association’s (LACBA) 15th Annual Environmental Law Fall Symposium: The Courts, the Climate, and the Deal: The Latest Developments. I’ll be on a panel discussing “Climate Change Regulation in California: 2020 and Beyond,” mainly focusing on the murky future of the state’s cap-and-trade program. That conference will be held tomorrow at the InterContinental Los Angeles Century City, from 11:30 to 4:3pm.

Hope to see you at one or both!

Rong-Gong Lin II at the Los Angeles Times tries to make the case that the Bay Area’s rail system is in decline while L.A.’s rail transit is ascending:

BART’s 44-year-old electric rail system is so decrepit that bay water is seeping into tunnels, ancient power systems surge so much they disable train cars, and even the steel rail itself has cracked and split off during the height of the morning rush hour.

Meanwhile, Los Angeles is in the midst of a major rail system expansion, building so rapidly that Metro’s 105 miles of rail is nearly equivalent to BART’s 107 miles. If two-thirds of voters approve Measure M — which would raise the sales tax by an additional half a penny for every dollar spent — Los Angeles County would see a dramatic expansion of rail over the next 40 years.

At a basic level, it’s hard to argue with the premise of the story: the Bay Area’s rail system is much older than L.A.’s, so the emphasis now is on repair. And yes, L.A. has been on a rail building boom since the passage of 2008’s Measure R.

But it’s otherwise hard to really compare these two regions. For example, it’s misleading to compare Metro’s 105 miles with BART’s 107 miles. The technologies are very different. Most of Metro Rail is an at-grade, street-level light rail line more like Muni streetcars in San Francisco. Only the Red/Purple Lines in L.A. are truly BART-like, and they can only accommodate six-car trains, not the ten-car trains with BART, which will limit ridership greatly.

And the current ridership stories are very different, too, with BART surging and LA flat-lining (as the article points out). The reason? San Francisco has had a lot of job growth in downtown in particular, whereas L.A.’s job growth is disbursed and therefore not always accessible to rail stations.

Finally, the idea discussed in the article that L.A. has an advantage as a single-county transit agency, versus the nine-county Bay Area, strikes me as strange. As I discuss in Railtown, my book on the history of Metro Rail, Los Angeles was hurt by having only one county cover the whole metropolis. The size and disbursed nature of the region made achieving an electoral consensus on where to site new rail lines almost impossible. In fact, the single-county system of L.A. is probably the biggest reason why the region is a generation behind San Francisco on rail.

But that criticism aside, I think it’s appropriate for L.A. to get excited about the recent progress on rail. But we’ll see what happens with this election: if BART gets its bond passed to fix its system and Measure M fails in Los Angeles, the premise of this story could soon start to fall apart.

The history of transit in Los Angeles County has too often been about parochial infighting and city feuding. It has thwarted many regional efforts to address the collective traffic and land use challenges in the region.

The history of transit in Los Angeles County has too often been about parochial infighting and city feuding. It has thwarted many regional efforts to address the collective traffic and land use challenges in the region.

This November, the story may re-appear, with southern L.A. County leaders threatening to torpedo the November sales tax measure for transportation, Measure M.

The Los Angeles Times is running my op-ed on the subject today. Here’s a snippet in response to south county residents’ concerns that they’re not getting enough out of the measure:

Residents of southern L.A. County are of course part of the greater region of Los Angeles — whether they work, visit, or shop in other parts of the county. Regional travel data from 2014 show that almost half of all peak period commutes from the Gateway and South Bay regions are bound for other parts of the county. These residents will benefit from mobility improvements throughout L.A. — not just the projects in their backyard. They’ll certainly stand to gain from some of the proposed signature projects, such as rail access to LAX and multiple countywide bus rapid transit lines.

So far the polling on the measure is looking pretty good, but with the two-thirds voter requirement, it will be an uphill battle. And that means that the measure could live or die by what voters in the southern part of the county decide on Election Day.

Successful rapid transit is not complicated. The best systems have a high percentage of people in the region who can walk to the stations. That means density, and that means density served by rapid transit.

Successful rapid transit is not complicated. The best systems have a high percentage of people in the region who can walk to the stations. That means density, and that means density served by rapid transit.

Now the Institute for Transportation & Development Policy has quantified how cities around the world fare (no pun intended) in these measures. In a new study called “People Near Transit: Improving Accessibility and Rapid Transit Coverage in Large Cities” [PDF], report authors Michael Marks, Jacob Mason, and Gabriel Oliveira found that cities like Paris and Barcelona score well both for population densities and for percentage of regional residents who can walk to transit (within one kilometer).

But the story is more mixed in cities like Washington DC. While the DC Metro scores pretty well in percentage of people in the city who live near transit (57%), only 12% of people in the region as a whole live near transit, due to the severe traffic-inducing sprawl of the greater metro area. Los Angeles fares even worse, with only 24% within the city near transit, and 11% of the region as a whole (of course LA’s system is less built out than DC’s).

It’s a variation of the study we released at Berkeley Law last year with Next 10, ranking California rail transit stations in part by their walkability.

And the same conclusions should be drawn from both studies: regions need to build more housing around rapid transit, and they need to make sure rapid transit serves only the densely built environment.

Laura Nelson reports in the Los Angeles Times on opposition to the November sales tax measure for transit (with some quotes from yours truly), localized in the southern part of the county:

But in the southern half of the county, where about one-third of likely voters live, some officials have refused to endorse the measure, questioning whether their constituents would see their fair share of projects.

Leaders in Torrance, Signal Hill and Carson have slammed Metro for not allocating more funds for local transportation needs, including street repairs. Others have groused that the $891-million Green Line extension from Redondo Beach to Torrance, a project discussed for years, is not slated to break ground for a decade.

Voters are free to choose as they like, but it’s hard to be sympathetic to these southern county leaders. As the article points out, they’ll receive plenty of return on the tax in terms of local road, transit and highway funds.

But more importantly, residents of southern L.A. county are part of the greater region of Los Angeles, whether they work, visit or shop in other parts of the county. They certainly benefit from an urban economy that functions with mobility for all. So it seems short-sighted to try to torpedo a rare chance at achieving the two-thirds voter threshold this November, just because a few of their local, desired projects aren’t rising to the top of the to-do list.

Ultimately, I’d like to see a statewide ballot measure to lower this threshold to at least 55%, so regions like Los Angeles aren’t held hostage to the whims of the few and forced to devise politically motivated transportation plans. But in the meantime, transit proponents are stuck trying either to placate opponents like these or hope that they can weather the storm come November.

Either way, the vote is likely to be close, evidently with little help from some local leaders.

Ed Edelman was the kind of politician that seems to be in short supply these days. As a city councilman and then county supervisor in Los Angeles until 1994, he was a public servant who truly cared about the greater good, even if it meant putting aside his own narrow political interest. And he played an unheralded but crucial role in launching LA’s Metro Rail system.

I got to see this integrity and public-mindedness first-hand in researching the history of the Los Angeles Metro Rail. As a law student at UCLA in 2004, I was busy writing about this history for a seminar paper in Professor Susan Prager’s California legal history class. Prager knew Edelman, then-retired, and recommended I meet with him to discuss this history. Over a warm beverage on campus that he insisted on treating me to, he spoke at length about the history of LA’s rail effort and offered to refer me to others who were involved.

I was just a student, and there was no glory or self-promotion at stake for him. He just wanted to help, and he cared about the issue of transportation in Los Angeles.

Based on his referrals, I got to interview a number of other key people involved in the early history of rail in LA, including Bob Geoghegan, Edelman’s former chief deputy (“if Ed thinks you’re a good guy, I’m happy to meet with you,” Bob told me beforehand by phone) and Marv Holen, who served on the early transit agency board.

Ed also gave me access to his donated papers at the Huntington Library, an institution that normally only allows PhD students to research in the archives. When the Huntington gave me some difficulty getting access that first day, Ed told me, “Just let me know if they give you any more trouble, and I’ll take my papers out of there!”

Between Ed’s papers, and Supervisor Kenny Hahn’s (also in the Huntington and accessible to me because of Ed), I found invaluable documents telling the story of LA’s early attempts at a modern rail system. My interview with him and his colleagues, as well as those archival documents, eventually led to the completion of my 2014 book Railtown. In short, I couldn’t have written it without him.

But lest you think my respect for Ed is all about these favors, my real admiration for him was actually inspired by what I saw in those documents. Time after time, the archival letters, articles, and memos revealed local politicians bickering and grandstanding about rail, so often just trying to serve their narrow interests and gain political support.

Yet it was clear from the internal debates and votes cast that Ed was a quiet and staunch supporter for a system that wouldn’t benefit his constituents much in the near term but would serve the greater good in Los Angeles. His district was not part of the densely populated core where the first lines would go. But he recognized the need to improve mobility across the region. He knew his constituents would benefit indirectly, even if there wasn’t a ribbon cutting in his district in the near future.

And when the time came in 1980 to vote in committee on a proposed ballot measure for rail, Ed was with President Carter at Camp David but jumped on a call from Geoghegan, his voting appointee. He took time out of that meeting to instruct Geoghegan to support it. The measure, Proposition A, passed by one vote in committee, and it eventually launched Metro Rail in Los Angeles.

With so much parochialism and selfishness these days, we should not forget the quiet example and leadership of Ed Edelman. For those who care about transportation and mobility in Los Angeles, he was a true founding father of the modern rail system, alongside Supervisor Hahn and Mayor Tom Bradley. And of course he championed other important causes during his time in office, as his obituaries recount.

On a personal level, I will always be indebted to him for helping me tell the story of Metro Rail. And I will remain inspired by his selfless example and the legacy he leaves behind for the people of Los Angeles and beyond.

Rest in peace, Mr. Edelman — a life well lived, in service to others.

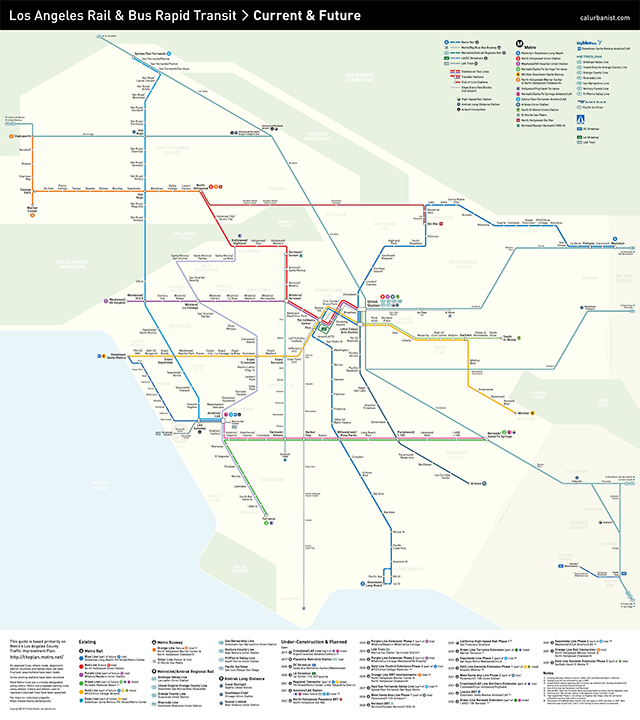

With a region as big as Los Angeles, it can be tough to visualize how new transit projects will fit into the landscape. And now that Measure M is on the ballot this November, a whole host of new projects are potentially at stake to add to the mix.

To make it easy for voters to visualize, amateur map-maker Adam Linder developed his own blinking GIF map, which has caught on with outlets like Curbed LA:

Adam describes why he developed the map in this interview with KPCC radio last week. Apparently my book Railtown was an inspiration for him to get into this issue, which is gratifying to hear. His map follows another one put together by a transportation consultant earlier this summer.

As the region contemplates Measure M this fall, grassroots efforts like these may end up making a big difference in swaying voters.

Jill Stewart is the campaign director for the Neighborhood Integrity Initiative, a Los Angeles measure proposed for the March 2017 ballot that would essentially freeze new development in the region. It’s fundamentally a NIMBY campaign in response to the region’s haphazard planning and entitlement process.

Jill Stewart is the campaign director for the Neighborhood Integrity Initiative, a Los Angeles measure proposed for the March 2017 ballot that would essentially freeze new development in the region. It’s fundamentally a NIMBY campaign in response to the region’s haphazard planning and entitlement process.

The Planning Report recently interviewed Stewart, in which she badly misstates urban theory (and evidence) on smart growth:

In a TPR interview in February, you said: “I have not been impressed by the new urban theory that very dense development through neighborhoods near bus stops, and so on, is going to reduce congestion. In fact, we’ve seen the opposite.” Is that assertion consistent with what you learned campaigning for NII?

Absolutely. I think most people are realizing that it is another failed urban theory put together by academics that have zero proof that it works.

The new mantra in every big city feels the same, essentially being: “We are all going to change the way we live.” I’m from Seattle, and I was there for a recent vacation. My Seattle friends and I were dreaming about a more intelligent way to go if we weren’t caught up in the urban planning religion that has gripped so many people. It’s comforting that a majority of residents are not gripped by this mantra. They do not buy into it.

When I discussed with my friends, we talked about how people are going to start working at home more. People are also starting to take Uber and Lyft more. It is a completely different world that is not built around fixed rail lines and coming into a big city center to work. The big city center is very 1980s or 1990s.

We came up with a way to resolve this: by rewarding the way people really behave. As more people work at home and stay off the roads, they should get a massive tax rebate, as long as they can prove it. Staying off the streets and not using the infrastructure should be rewarded. Often, the city of LA adds taxes to people who work from home. That’s backwards.

The urban planners are stuck in a different world. They are saying that everyone needs to move close together and cram their children into places where there is nowhere to play. The theory that people enjoy living around the noise and congestion is wrong, and we need to respond to how people really live.

Where to begin? First, I’ve yet to meet any urban planner who says that everyone “needs” to move into compact, transit-friendly neighborhoods. Rather, the argument is that we don’t have enough of these neighborhoods, at least at affordable prices, to even give people the option of living there, if they seek a lifestyle that is not car dependent. Los Angeles certainly provides plenty of options for suburban-style living, but not so much for low-crime, walkable, transit-friendly neighborhoods. And when the region does provide those options, the demand is through the roof, leading to high rents and home prices that keep out all but the wealthiest.

Second, the urban theory of smart growth has never been about “reducing congestion.” With growth comes some congestion, but growth in the right places means people have the option to drive less and therefore spend less time stuck in traffic. So the theory is really about reducing per capita driving miles.

And there’s plenty of evidence this works. Just look at any map of greenhouse gas emissions per capita, which is largely a function of vehicle miles traveled: it’s always lowest in compact urban centers near transit. People in these areas don’t need to spend much time in traffic, if at all.

But ultimately, if you’re simply anti-growth — or anti-growth anywhere near you — then none of this information really matters. But if you care about housing affordability, the environment, and creating better, more connected and convenient neighborhoods, then it’s important to get the facts straight.

It’s a subject that never ceases to amaze me. As we face a growing infrastructure crisis across the country, with a strong need for more transit infrastructure to serve a growing population that is tired of driving and traffic, we simply can’t build like we used to. I wrote a report about it for UCLA Law back in 2014 called Back in the Fast Lane, which offered some ways to speed up the planning and building process for new transit projects.

Alex Zimmerman at Atlas Obscura covered the topic last year, interviewing a transit historian in New York. The article’s explanation for why it takes longer to build that city’s subway now than it did in 1900? Zimmerman mostly attributes it to increased labor and safety standards, but other factors were at play:

Also crucial to the original tunnel’s speedy construction was the sheer number of workers deployed and the conditions they were expected to endure. Somewhere between 7,700 and 12,000 people were involved in building the first line, according to Desjarlais, and most of the workers wielding pickaxes were only bringing home around $1.50 per day [equivalent to about $40 a day in 2016 dollars].

“You have these guys down there who are literally banging at the rock with shovels,” says Newman. And it’s not like there were generous benefits or protections. “I think they were just working insanely. There were many fewer regulations in terms of public safety [and] public health.”

Nobody can argue with the need for modern safety standards. And the article also discusses reasonable delays stemming from the complex construction process now with more modern utilities in the ground.

But some of the delays are procedural and political, such as more deference to the needs of local property owners and more extensive environmental review and mitigation. And of course, we shouldn’t ignore the possibility of weak public oversight and management of these projects. The problem is especially worrisome given the large amount of public money at stake and the potential for the corrupting influence of campaign contributions from contractors to the local decision-makers who award the construction contracts in the first place.

Ultimately, these long delays are a political problem we have to address. Failure to do so risks continued environmental and economic degradation and a backlash from the voting public for over-promising and under-performing on these crucial transit projects.

What started with Proposition A in 1980, continued with Proposition C in 1990, and then bolstered with Measure R in 2008, will now be tested once again officially as Measure M in November. I’m talking of course about Los Angeles rail transit plans, which once again hinge on another voter-approved sales tax measure.

The measure promises a host of new transit plans for the region, as illustrated with this map as a side project from a Nelson/Nygaard employee:

A few notable things stand out about this measure. First, there is no sunset date, which is a departure from Measure R’s 30-year limit. The justification is that the measure includes operating funds for transit, which address a need that doesn’t sunset.

Second, the new projects cover some vital links in the region, most prominently a public-private toll road and rail tunnel connection from the Westside to the Valley underneath the Sepulveda Pass. It also includes rapid bus down the high transit-usage Vermont Avenue and Lincoln Boulevard along the coast and connections to the eastern part of the county (including the gap between the Green Line in Norwalk and the Metrolink station).

There will be a battle royale to try to surmount the two-thirds voter approval hurdle this November, and the plan clearly contains a lot for every part of the county, including some unfortunate projects (the “High Desert Corridor” freeway stands out as particularly egregious). But it’s hard to blame Metro for trying again, given the success in 2008 and near-miss in 2012 with Measure J, along with the scale of the need.