For those in Los Angeles, I’ll be giving an evening talk on Wednesday, January 25th on the past and future of Metro Rail, based on my book Railtown. The event is hosted by UCLA’s Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies and will take place from 5:00 – 6:30pm in Room 5391 of the Public Affairs Building. It’s co-sponsored by the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs, Department of History, and Institute of Transportation Studies. More information and registration is available on UCLA’s event page. I’ll have book copies available for sale and to sign. Hope you can attend!

For those in Los Angeles, I’ll be giving an evening talk on Wednesday, January 25th on the past and future of Metro Rail, based on my book Railtown. The event is hosted by UCLA’s Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies and will take place from 5:00 – 6:30pm in Room 5391 of the Public Affairs Building. It’s co-sponsored by the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs, Department of History, and Institute of Transportation Studies. More information and registration is available on UCLA’s event page. I’ll have book copies available for sale and to sign. Hope you can attend!

And speaking of Railtown and UCLA, I’m belatedly sharing this 2016 review of the book by UCLA assistant professor of urban planning Michael Manville in the Journal of Planning Education and Research. Manville starts with some compliments:

This is a good book. Anyone who thinks they might like it probably will. Elkind is a talented writer and synthesizer of information, and the story itself is one that (for transportation nerds, at least) has long begged to be told. Elkind has scoured the archives and interviewed many of the participants in his story. I have lived in LA for more than ten years, studied transportation there, and rode many of its trains, and I still learned a lot reading Railtown.

However, he also offers some pointed critiques:

The book’s great weakness, to me, is that it takes rail’s necessity as a given. In doing so, Railtown assumes away the great unanswered question of modern rail: Why do we want it? What problem does it solve? There are times in Railtown…where rail seems almost an end in itself. Any proper city has rail, so rail is successful when we successfully build it. But in a city with scarce resources and vast needs, that is no way to justify enormous public expenditures.

It’s ironic to read this complaint because it is the exact mindset that I criticized early rail leaders for having in promoting rail. For me, rail is a necessity for Los Angeles because it provides the best transportation infrastructure around which to channel future growth in the city (with the big unanswered question as to whether or not local leaders will allow that growth to happen). Otherwise, future growth will either be disorganized and stuck in urban gridlock or pushed out as car-dependent sprawl. And at the densities that Los Angeles would need to build new housing to meet market demand and accommodate existing and future residents, only rail can efficiently move those large numbers of people (again, assuming the density comes to fruition).

It’s also worth mentioning that a corridor like along Wilshire Boulevard already has the density needed to support rail and is a prime candidate for such a project as-is, just given the existing conditions there.

Manville then continues with the critique that rail won’t address the region’s underlying transportation challenges:

More train riding is not the same as less driving. Why should LA (or any city) descend into debt to subsidize rail when it could just stop subsidizing cars? Angelinos drive as much as they do because their government routinely widens roads, requires parking with every new development, and most of all lets drivers use the city’s freeways and arterials—some of the most valuable land in the United States—for free. The projects described in Railtown are distractions from, not solutions to, these problems.

I wholeheartedly agree with Manville on this point. If the goal is to reduce traffic congestion, rail is not the answer, and I never make that claim in the book. The preferred solutions for addressing the traffic problem in Los Angeles would involve congestion pricing and ending subsidies for driving, as Manville describes.

But there’s no reason why the region can’t do both: build alternatives to driving like rail transit and also stop subsidizing auto driving. In fact, both are needed simultaneously, and I don’t see any evidence that rail distracted the public from these other solutions. The reality is that rail is the politically easier thing to do, so it gets done first. But subsidies for autos will be easier to remove once there is a viable alternative in place, so rail could provide the conditions necessary to earn public support for the steps Manville envisions. After all, San Francisco was able to stop subsidizing cars and become a “transit-first” city only after it developed a robust transit system, which included BART.

Overall, I agree with much of the book review and appreciate Manville’s comments. You can read the whole thing and come to the talk on the 25th to discuss and hear more!

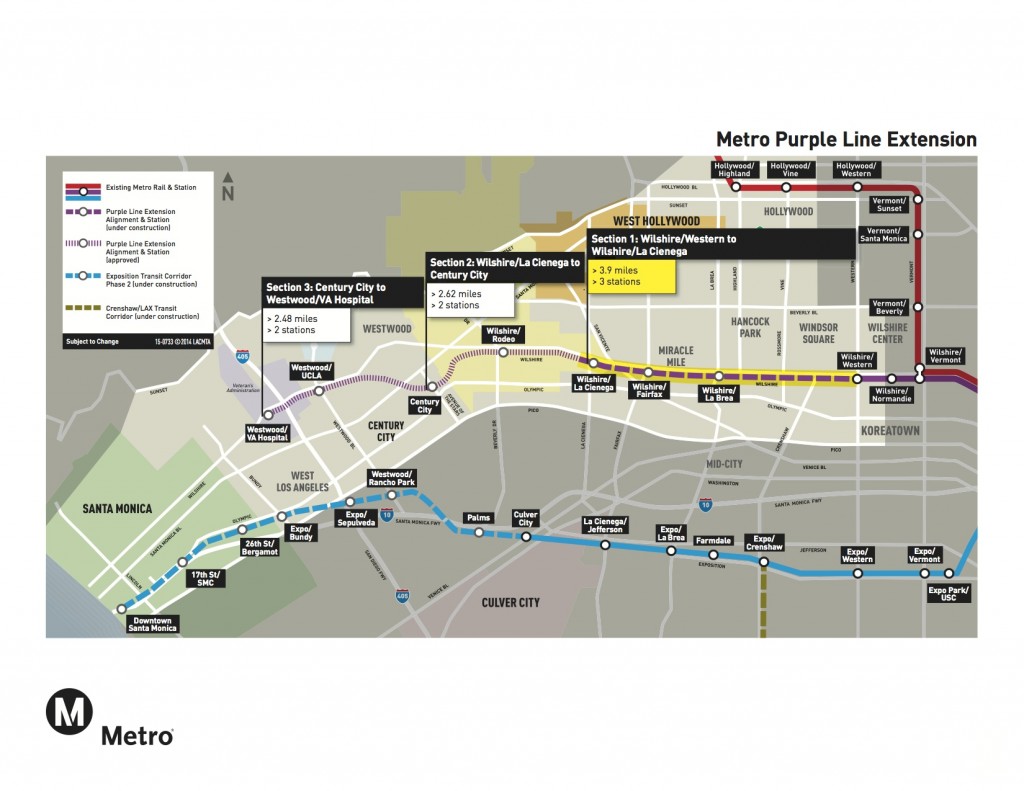

Big transit news in Los Angeles from the outgoing Obama Administration: the federal government is giving L.A. Metro $1.6 billion to build the second phase of the Wilshire Boulevard subway to downtown Beverly Hills and Century City. The money is mostly in the form of a grant but also includes a $300 million loan.

This rail project is the most important in Southern California — if not the western United States — given the densely populated nature of this corridor (most dense west of the Mississippi River). The project has languished for decades due to political resistance from those living along the corridor as well as the high price tag for a subway, as I documented in my book Railtown. That resistance has finally been overcome due to frustration with traffic and pro-transit demographic changes in Los Angeles County.

As Metro’s The Source blog describes:

•The money is for the 2.6-mile second phase of the Purple Line Extension that will run between Wilshire/La Cienega Station and Century City. Two stations are included in the second section: Wilshire/Rodeo in downtown Beverly Hills and Century City at the corner of Avenue of the Stars and Constellation Boulevard.

•The first section of the Purple Line Extension is under construction and will run for 3.9 miles between Wilshire/Western Station and Wilshire/La Cienga with stations at Wilshire/La Brea, Wilshire/Fairfax and Wilshire/La Cienega.

According to Los Angeles Times reporter Laura Nelson, Metro CEO Phil Washington also just made a big promise about finishing the entire line to Westwood/UCLA quickly, given the recent passage of Measure M by L.A. County voters:

According to Los Angeles Times reporter Laura Nelson, Metro CEO Phil Washington also just made a big promise about finishing the entire line to Westwood/UCLA quickly, given the recent passage of Measure M by L.A. County voters:

Metro CEO Phil Washington: “Our plan is to do the entire Purple Line before the Olympics. … If it doesn’t happen by 2024, you can fire me.”

— Laura J. Nelson (@laura_nelson) January 4, 2017

It’s good news for the region for this long-overdue project. And it’s also important to keep in mind that this is partly about Los Angeles getting its tax dollars back from the federal government. Californians pay more in federal taxes than they receive, so it’s nice to see that money coming back for much-needed infrastructure. Let’s hope the new congress and administration keep that in mind when they consider federal spending going forward.

Transit advocates will now need to ensure that the project gets built quickly and under budget. The hundreds of thousands of commuters and residents along the corridor deserve it, and the rest of the region deserves not to have cost overruns sap funds for other needed projects.

But in the meantime, it’s an announcement worth celebrating, especially as a parting gift from an outgoing, transit-friendly presidential administration.

Congratulations to Miguel Del Mundo, winner of TransportiCA’s July book club contest featuring my book Railtown. To win, Miguel had to answer three questions based on the book, which covered the history of the Los Angeles Metro Rail system. Answers in bold:

1) With the defeat of Measure A in 1974, Mayor Bradley explained residents received this item in the mail the weekend before the election, which had a major effect on the outcome: property tax assessment.

2) When Tom Bradley was first elected Mayor of Los Angeles in 1973, he made a promise that he would have a rapid-transit system in construction how many months after taking office? 18.

3) LA County Supervisor Baxter Ward created what transit proposal, later defeated by county voters, and modified later under a new name and scale? Sunset Coast Line (1976), later Sunset Coast Limited (1978); both were defeated.

For his efforts, he won a signed copy from me. Here’s a picture of Miguel enjoying the book in an appropriate location:

L.A. Metro spent $1.6 billion to widen the 405 freeway from the San Fernando Valley to the Westside. Now the New York Times has to fill paragraphs exploring the obvious: was it a waste of money?

Well, here are the initial results on what was supposed to have been a project with multi-decade benefits for congestion relief:

Peak afternoon traffic time has indeed decreased to five hours from seven hours’ duration (yes, you read that right) and overall traffic capacity has increased. But congestion is as bad — even worse — during the busiest rush hours of 4:30 to 6:30 p.m., according to a study by the county Metropolitan Transportation Authority.

To be fair to the project’s proponents, it also added a carpool lane and seismic retrofits for overpasses, both of which will be useful going forward.

But the idea that widening a highway relieves congestion? We should have put that one to bed a long time ago. Increasing capacity just induces more demand, as this UC Davis brief documents [PDF].

If the goal is to reduce congestion, local governments should implement congestion pricing to discourage solo and optional trips. If the goal is to expand capacity, they should look into bus-only lanes, new bike infrastructure, and new transit capacity. Congestion pricing can meanwhile help to fund some of those options.

Otherwise, consider $1.6 billion investments like this one to be a giant waste of money.

California’s transportation infrastructure has been steadily declining for years, a victim of neglect from dwindling gas tax revenue. As a result, local governments have been raising their own taxes to fund needed repair and expansion. But these efforts can undermine environmental goals by encouraging driving and more sprawl.

As the state’s just-released 2030 draft scoping plan for greenhouse gas reduction makes clear [PDF], reducing vehicles miles traveled (VMT) is essential to achieve sustainable growth and emissions in California:

While the majority of the GHG reductions from the transportation sector in this Discussion Draft will come from technologies and low carbon fuels, a reduction in the growth of VMT is also needed. VMT reductions are necessary to achieve the 2030 target and must be part of any strategy evaluated in this plan. Stronger SB 375 GHG reduction targets will enable the State to make significant progress towards this goal, but alone will not provide all of the VMT growth reductions that will be needed. There is a gap between what SB 375 can provide and what is needed to meet the State’s 2030 and 2050 goals. More needs to be done through continued land use changes, synergies with emerging mobility solutions like ridesourcing, and changes in travel behavior, especially among millennials.

Transportation investments can either encourage or reduce VMTs, if they go to automobile infrastructure instead of walking, biking and transit projects.

Now that Democrats have a super-majority in both houses of the legislature, they should prioritize new transportation spending in VMT-reducing investments. The best way would be to replace the gas tax with a mileage-based fee, with the revenue going only to maintenance of existing infrastructure and new VMT-reducing projects. The necessary two-thirds vote for that revenue is now possible, at least in theory.

In the long run, it could be the most important environmental legislation for the state to come out of this session of the legislature.

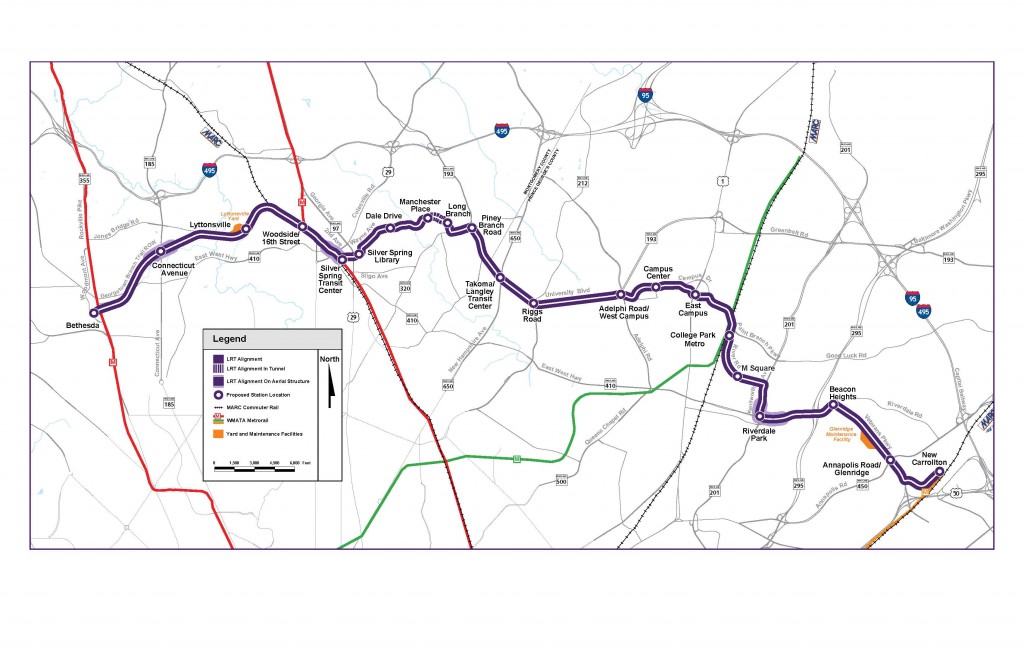

No, not the L.A. purple line subway down Wilshire. It’s the Maryland light rail purple line, providing a critical rail connection between spokes of the beleaguered Washington DC Metro. Think of it as the rubber tire connecting the end of the Metro spokes, per this map:

Last year, I triumphantly blogged that the rail line was approved after the Republican governor of Maryland had a change of heart from his highway-favoring ways. I took credit because I had just given a talk on rail in Washington DC (victory has a thousand parents).

Last year, I triumphantly blogged that the rail line was approved after the Republican governor of Maryland had a change of heart from his highway-favoring ways. I took credit because I had just given a talk on rail in Washington DC (victory has a thousand parents).

But this year, a judge has put the kibosh on the line, due to a lawsuit by affluent homeowners upset at losing the current leafy bikeway and trail to a rail line for the masses. As Construction Dive reported, the gist of the decision is that new environmental analysis is now required to revise the ridership estimates. It seems that falling DC Metro ridership, which purple line backers relied on for their analysis, need to be taken into account to revise the projections downward.

The decision is jeopardizing $900 million in federal funds already committed, and it may kill the project entirely if the new numbers don’t pencil well. As a backup, the rail line could turn into a busway, but it would be a major setback for transit advocates.

It’s another example that contentious rail projects and litigation are not just a feature of California’s politics, and that the usual suspects of affluent homeowners groups hold sway across the country when it comes to these critical infrastructure projects.

Because it definitely had nothing to do with my presentation.

Pulitzer Prize-winning writer Edward Humes spoke to the Los Angeles Times‘ Patt Morrison to complain about the just-passed Measure M sales tax measure to boost transportation in Los Angeles. He argues it won’t help traffic and is missing out on big technological shifts:

But what’s missing are transformative visions that are necessary to get people to really change the way they get around. There was a survey done last year of transportation planning for the largest municipalities and counties in America, and something like only 7% of their plans even addressed the big changes that have arrived recently in mobility or are coming soon — ride-sharing services, automation, driverless cars.

We know they’re coming — there’s nothing in Measure M that even addresses these transformative developments that 1980s-style transportation plans wouldn’t know to address. It’s like we’re not acknowledging that things are changing very rapidly in the transportation space. We’re going to just go out and lay down more asphalt and lay down more rail and hope for the best. It’s not going to work.

He recommends doubling down on these technology changes with first/last mile automated vehicles, putting big rigs in carpool lanes, and relying on automated buses in dedicated lanes.

I agree with him that Measure M won’t solve traffic by itself: the only way to do that, barring huge spikes in fuel costs, is congestion pricing.

But nothing about Measure M precludes what Humes advocates. And in the meantime, it will pay for important new infrastructure — including maintenance of existing infrastructure — that a growing population will rely on for mobility. We need the new capacity to move people that rail and buses bring, and Measure M will boost ridership across all rail lines by finally giving the region comprehensive rail coverage to fill in the missing pieces.

On automation, Humes doesn’t seem to acknowledge that more driverless cars could mean a huge spike in traffic, which could push more people to want to use the rail or bus networks that Measure M will fund. His solutions (such as encouraging shifts in employment hours) will only provide temporary respite from induced demand.

Meanwhile, we can acknowledge that Measure M is probably not enough by itself to address all the mobility challenges in Los Angeles, but it’s a necessary part of the solution. For example, the region will need smart policies on automated cars. But these vehicles will still rely on and complement improvements in infrastructure from Measure M, just like investments in bus-only lanes funded by the measure can eventually accommodate the automated buses that Humes envisions.

Finally, Humes never discusses land use (at least in this interview). But that issue is central to the mobility concerns. The region needs to concentrate all new growth around transit corridors, and Measure M can provide the network to get new residents and workers to move about without adding to congestion. Measure M also provides new development opportunities to channel growth around transit, which is the only sensible recipe for future growth.

I think it’s worth thinking through the issues that Humes describes, and a visionary voice can be powerful. But we shouldn’t dismiss so readily the incredible funding tool that Measure M gives the region to address its transportation challenges.

Yes, there’s a lot happening today in the national election. Lost in the shuffle though are three big initiatives before some California voters that could have a big impact on the state’s transit and development future.

Yes, there’s a lot happening today in the national election. Lost in the shuffle though are three big initiatives before some California voters that could have a big impact on the state’s transit and development future.

- Measure RR to restore BART: this is an unusual transit measure because it’s one of the first I’ve seen that makes no promises about expanding transit service. Instead, it seeks to issue bonds solely for maintenance of the aging San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) system. The bond issue will require two-thirds approval, which is a high hurdle. But failure to pass means that BART will continue to have reliability issues and won’t be able to increase train frequencies to meet growing ridership. It’s a nod to the reality of what happens to rail lines with too much neglect, as Washington DC is now experiencing.

- Measure M to boost transit (and transportation) in Los Angeles: the County of Los Angeles is going back to the voters for another transportation sales tax measure. If it passes, without a sunset date like 2008’s Measure R, it will solidify Los Angeles as a national leader in building rail transit and will transform the city for the rest of this century. That will be a total and major shift for the region that once sold the image of car-oriented suburbia to the world.

- Santa Monica’s LV measure to prevent new housing: this is more of a bellwether initiative that could be a harbinger of a backlash against pro-housing policies throughout the state. Santa Monica is a wealthy coastal community that recently got a multibillion, taxpayer-funded rail line delivered to its shores. But homeowners there have already helped squash one big development project next to a rail station, and this initiative would prevent any substantial new housing from being built, under the guise of direct democracy. Its effect would be to depress transit ridership on the new rail line, greatly escalate home prices and rents by artificially restricting supply, and continue the trend of core urban residents forcing new arrivals to the sprawl periphery in search of affordable homes, far from well-paying jobs. While Santa Monica is only one community, the success of the initiative could be a prelude to further anti-housing victories in greater Los Angeles and the state.

So while the nation will be focused on bigger elections, these three will in their own way have a significant effect on the future of California’s cities, environment and economy. Another reason to stay tuned!