David Dayen in the American Prospect has a long piece describing the “revolt” in Los Angeles against the automobile and how the city is transforming before our eyes:

In January, the city received $1.6 billion in federal support for the Purple Line, and Mayor Garcetti has asked the Trump administration for more, to move up subway completion from 2035 to 2024, in time for that year’s Summer Olympics, for which L.A. is one of the two finalists. “We have become the infrastructure capital of the world,” says Phil Washington. “With two NFL teams, a rail spur to that stadium, the possibility of the Olympics, it creates this economic bonanza, what I call a modern-day WPA [Works Progress Administration].”

The risk, as Dayen points out, is that the Trump administration will withdraw federal funds, leaving Los Angeles to pay for much of this transformation on its own and essentially backfill the missing the federal dollars.

But cities have gone that way before. The Bay Area, for example, largely built BART on its own in the 1960s and 1970s, as the federal government didn’t provide funding for rail transit at the time.

The difference now is that costs have gone way up, making it harder for a region like Los Angeles to fund this transformation without getting its share of federal tax dollars back to reinvest locally.

The article also rightly points out (with some quotes from yours truly) that the great unanswered question is whether the region will allow growth to follow this new transportation infrastructure. Poor land use decision-making is what got the region into the mobility and air quality mess its in. Only smart growth near rail transit will provide residents the option of a way out.

But the necessary transit backbone, as Dayen describes, is finally coming into place, giving local leaders a viable foundation for rebirth.

Last night the California Legislature scored a super-majority victory to extend the state’s signature cap-and-trade program through 2030. It was a rare bipartisan vote, although it leaned mostly on Democrats. My UCLA Law colleague Cara Horowitz has a nice rundown of the vote and its implications, as does my Berkeley Law colleague Eric Biber on the bill.

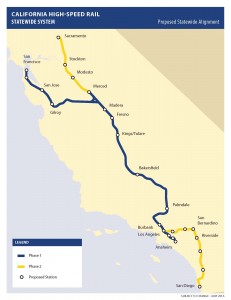

Lost in the politics is what this means for high speed rail. The system has a fixed and dwindling amount of federal and state funds at this point, and it’s relying on continued funding from the auction of allowances under cap-and-trade to build the first segment from Fresno to San Jose and San Francisco.

Lost in the politics is what this means for high speed rail. The system has a fixed and dwindling amount of federal and state funds at this point, and it’s relying on continued funding from the auction of allowances under cap-and-trade to build the first segment from Fresno to San Jose and San Francisco.

If the auction was declared invalid or ended at 2020 with depressed sales, the system would be in major jeopardy of collapsing before construction even finished on the first viable segment. Now it has some assurance of access to funds.

But of course it’s not that simple. The bill that passed yesterday has diminished available funds set aside for the programs that have been funded to date with cap-and-trade dollars. As part of the political compromises, more auction money will now go to certain carve-outs, like to backfill a now-canceled program for wildfire fees on rural development.

And another compromise may put a ballot measure before the voters, passage of which would require a two-thirds vote for any legislative spending plan for these funds going forward. That means Republicans — who generally hate high speed rail — would be empowered to veto future spending proposals.

Still, high speed rail once again has a lifeline, as do the other programs funded by cap-and-trade, such as transit improvements, weatherization, and affordable housing near transit. It’s an additional victory beyond the emissions reductions that will take place under this extended program.

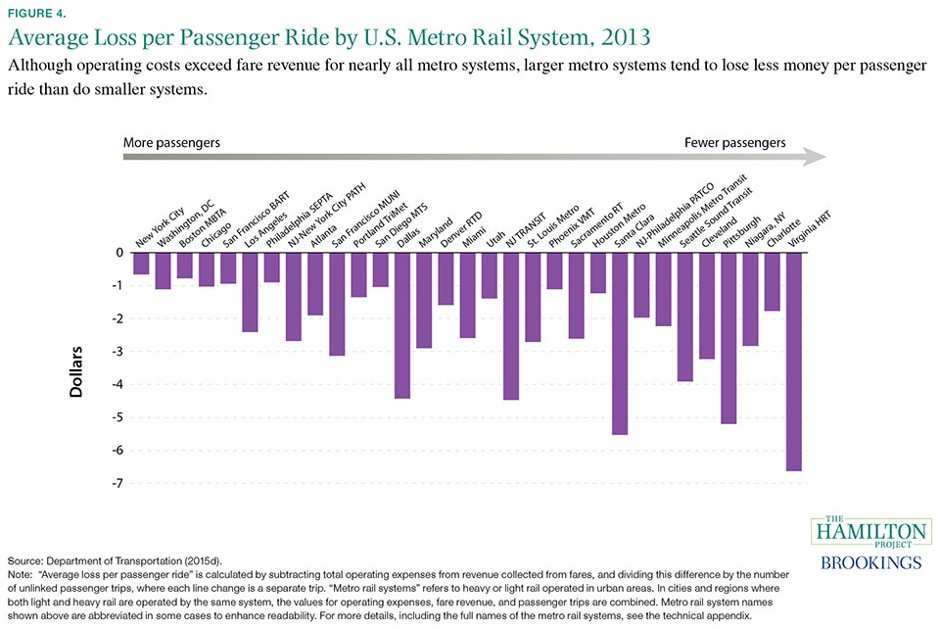

We don’t need rail transit systems to make money. None of them do, and neither do roadways for that matter (gas taxes pay for most of that infrastructure).

What’s more, rail transit systems have huge economic and environmental benefits that aren’t captured in the fares. They can mean less driving, more downtown and station-area investment, less pollution, and better quality of life. Plus they provide convenient alternatives for those who don’t or can’t drive.

But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t care about how cost effective these systems are. To that end, Eric Jaffe at CityLab points to a Hamilton Project chart showing how much the major rail transit systems in the U.S. lose:

Some interesting things jump out at me from the chart:

- Los Angeles is a bit of an outlier (in a bad way) with relatively high ridership but heavy losses compared to its nearby peers, like BART and the Philadelphia system. My guess it’s related to the lack of distance-based fares on the trains, as people can take long rides on LA rail but pay as if they just went one stop.

- San Francisco’s MUNI system is a surprising money loser. Those trains are packed, so I’m not sure what the problem is. It could be high operating expenses, rather than a revenue problem. The same dynamic could also be affecting New Jersey transit and New York’s PATH.

- Santa Clara’s VTA is one of the worst in the country. Not surprising. We graded it and its station-area development harshly in our 2015 report comparing California urban rail transit systems and their station neighborhoods (although San Diego’s system also graded poorly but does not have heavy losses, per this chart).

The bottom line: transit systems need to keep their operating expenses down while boosting revenue. My guess is operating costs are mostly about labor and security expenses. But regardless, a straightforward way to boost revenue is to increase ridership by serving only densely populated neighborhoods.

If transit systems can achieve those two goals, they’ll rate highly on charts like these.

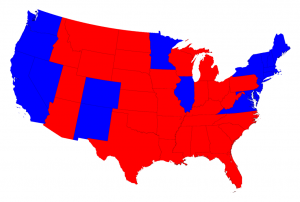

Richard Florida argues in Politico.com that the election of Trump should bolster calls to devolve more power to states and specifically cities. While he acknowledges that some of this smacks of “sore loser” federalism, it would address a growing structural problem in governing a nation as large and diverse as the U.S.:

Richard Florida argues in Politico.com that the election of Trump should bolster calls to devolve more power to states and specifically cities. While he acknowledges that some of this smacks of “sore loser” federalism, it would address a growing structural problem in governing a nation as large and diverse as the U.S.:

Even on the domestic level, though, the modern-day presidency is crazy when you think about it: Why would a nation of 300 million-plus people, 50 states, 350-plus metro areas, 3,000-plus counties, and thousands and thousands of cities and communities choose to vest so much power in one person and one office? If there were any doubt about it before, we now know for a certainty that our current governance system, with its packing of humongous power in a unitary executive, is vulnerable to catastrophic failure. In addition to our well-understood horizontal separation of powers among the executive, legislative and judicial branches of government, the vertical separation of powers among the federal government, the states and the local level provides a further set of safeguards and protections that we can and must use better. As a number of large corporations have discovered, devolving decision-making from executive suites to work groups on the factory floor drives huge productivity gains.

I’m sympathetic with much of the progressive policy aims for the federal government over the last century or so, from basic social safety nets to labor and environmental standards to civil/women’s rights and infrastructure investment. But Florida’s point is hard to argue with. In a country as large and diverse as ours, with so much power now concentrated in the federal government, each election becomes a divisive tug-of-war now prone, as Florida says, to democratic (small “d”) catastrophe.

Some of this “devolution revolution” could be straightforward, such as allowing states more flexibility on infrastructure investment. As a pro-transit person, the federal government hasn’t been great on this issue anyway, mostly funding highways, and in recent years, not funding much of anything.

But Florida doesn’t grapple with some of the hard choices and trade-offs this approach would entail. Are we comfortable as a nation allowing some states to continue discriminating against women, minorities and religious groups? To pollute their environment, when the effects might spill over to neighboring states? To weaken labor and safety standards? And of course to roll back social safety nets like Medicare and Social Security?

The upside, perhaps, is that states would be freer to solve these problems themselves, and we’d get a true laboratory effect going. People would be free to move to more successful and tolerant states, as the Great Migration exemplified. We’d also potentially ratchet down the growing tension in this country between affluent, urban areas and economically stagnant and declining rural regions.

But it would come at a cost to specific policies and policy goals that need to be addressed head on.

It’s worth considering as a long-term response to a problem that is much bigger than just one presidential election, and that won’t be resolved with just a change in leadership.

With so much noise coming out of Washington DC these days, from phony bill signing ceremonies to endless provocative tweets and misinformation, it’s easy to lose sight of the real, consequential policy battles going on at the moment.

On the environment, the big battle in Congress will take place over the budget late this summer. A temporary stopgap measure helped preserve funding for key environmental initiatives, such as clean energy research and transit projects like Caltrain electrification. But that bill just kicked the can down the road to September, when the government must act to avoid a shutdown.

The Trump administration’s proposed budget would zero out basically all environmental programs, including all new transit projects. I’m following the fate of clean energy research at the uber-successful ARPA-E in particular, at the Department of Energy:

September is now the new showdown date for the future of federally-funded breakthrough energy research in the United States. And if Trump has his say, the September fight could be waged in a higher-stakes, post-filibuster, 51-votes-to-pass-a-bill Senate. (Regardless, apparently, of any consequences for Republicans when Democrats next control the White House and/or Congress.)

On transit, the administration wants to end all federal support for urban transit projects, essentially ending a half-century of federal involvement in this area. As Transportation for America writes:

The administration reiterates their belief that transit is just a minor, local concern.

“Future investments in new transit projects would be funded by the localities that use and benefit from these localized projects,” they write, making it clear that they see no benefit in providing grants to cities of all sizes to build new bus rapid transit or rail lines, or expand existing, well-used lines so they can carry more passengers.

The administration even uses the example of local cities approving their own funding measures for transit as a reason to discontinue federal support, when those local measures were actually sold as ways to leverage federal dollars in this longstanding partnership.

The good news is that many of these programs and initiatives have bipartisan support. We saw that in action with the stopgap measure passed this spring. But that support will be put to the test as we witness an assault on federal dollars for the environment and public health like we’ve never seen before.

Perhaps no other local land use issue can be as important — and detrimental — to quality of life, convenience, and the environment as parking. High local parking requirements for new development drive up home prices and rents, induce more traffic, and waste space. And poor parking management of existing spaces leads to more air pollution and congestion.

Yet too often failed parking policies soldier on, based on zombie regulations from outdated planning guidelines and the fear of making destinations inconvenient to access by private cars. It’s particularly a waste in transit-oriented, infill neighborhoods where convenient alternatives to driving exist.

With that in mind, I was pleased to co-author an op-ed in today’s Los Angeles Times with Mott Smith, director of the nonprofit Council of Infill Builders. The organization just released a new report Wasted Spaces: Options to Reform Parking Policy in Los Angeles at Los Angeles City Hall a few weeks ago, and the op-ed contains recommendations based on that publication.

The issue of parking policy reform is particularly acute in Los Angeles, where 14% of the county — over 200 square miles — is now dedicated to parking. After over a half-century accommodating the automobile at all costs, the region now has 18.6 million spaces for 3.5 million housing units, or 3.3 spaces per vehicle.

To bring reform, Mott and I argue in the piece that:

Local leaders should prioritize urgent reform of L.A.’s parking policies, particularly in transit-oriented neighborhoods, with the following measures:

-

Eliminate or reduce parking requirements for any new development projects.

-

Ensure that revenue from parking benefits the local community.

-

Rather than mandate new parking requirements in the zoning code, promote shared parking and alternative transportation options.

Local leaders should start these reforms now, or risk continuing the failed legacy that has been so stifling for mobility, affordability, and air quality in the region.

Falling transit ridership is a nationwide problem, but it’s particularly a setback in Los Angeles, which is investing like crazy in transit due to two recently passed transportation sales tax measures. Laura Nelson covered the recent ridership decline in the Los Angeles Times and what L.A. Metro plans to do about:

Metro bus ridership fell 18% in April compared with April 2015. The number of trips taken on Metro buses annually fell by more than 59 million, or 16%, between 2013 and 2016.

A recent survey of more than 2,000 former riders underscores the challenge Metro faces. Many passengers said buses didn’t go where they were going — or, if they did, the bus didn’t come often enough, or stopped running too early, or the trip required multiple transfers. Of those surveyed, 79% now primarily drive alone.

In an attempt to stem the declines, Metro is embarking on a study to “re-imagine” the system’s 170 lines and 15,000 stops, officials said. Researchers will consider how to better serve current riders and how to attract new customers, and will examine factors including demographics, travel patterns and employment centers.

Meanwhile, as Metro explains in its outlet The Source:

Metro has not embarked on such a systemwide effort since the 1990s so it is timely given the significant expansion of the Metro Rail system this century, growth of municipal operator services and the popularity of other transportation options (i.e. ride hailing services such as Lyft and Uber).

As I blogged earlier, it was easy to dismiss prior reports of falling ridership, but now is definitely a good time to take it seriously.

But Metro won’t exactly be hurrying to get to the bottom of this. The bus system review isn’t planned to be completed until April 2019, which will then require public hearings later that year. So any actual changes won’t go into effect until December 2019 — at the earliest.

Two years seems like a really long time to study this issue, although Los Angeles does have an enormous system. Still, a little urgency could be in order. And in the meantime, the agency could focus on one immediate step that is guaranteed to boost ridership: require local governments with major transit stations to relax restrictions on adjacent development.

And Metro could start with the recalcitrant neighborhoods around the new Expo Line.

Otherwise, we’ll have to wait a while on any results from the bus study.

New apartments by the downtown Santa Monica station, which ain’t happening hear other stations along the Expo Line.

The Expo Line from Downtown L.A. to Downtown Santa Monica travels a highly congested corridor in the job-rich but housing-poor Westside of L.A. While the multibillion rail line has been successful so far in exceeding ridership projections, it could still fail to live up to its full potential unless the station neighborhoods allow more compact, rail-oriented development to generate enough riders for the line and minimize the taxpayer costs. Not to mention this part of town badly needs housing in areas that don’t require car commuting.

So it was a big deal last month when the City of Los Angeles released the draft Exposition Corridor Transit Neighborhood Plan, which governs the land use for the neighborhoods around the line within the City of Los Angeles.

Steven Sharp over at Urbanize LA took a deep dive into document. His verdict? The plans are tepid at best with no strong vision for the kind of density required to make good use of the multi-billion rail line:

While a small but significant step towards a more transit-oriented future for communities surrounding the Expo Line, the Expo TNP [transit neighborhood plan] falls short in terms of scale and scope when compared to planning around rail lines in other major cities.

On the opposite side of the country, Washington Metro stations are surrounded by dozens of walkable town centers in southern Maryland and northern Virginia. Other existing commercial hubs, such as Tyson’s Corner, are being gradually retrofitted for pedestrians following the introduction of passenger rail service.

In contrast, the proposed Expo TNP walks a fine line between maintaining the status quo and creating the transit-oriented communities implied by the project’s name. The station subareas which would be rezoned for higher density development represent less than 13 percent of the total land area encompassed by the Expo TNP, as the vast majority of properties are excluded from land use changes on account of their R1 and R2 zoning.

The properties that would be upzoned under the plan are almost exclusively commercial and industrial sites, where current occupants are less likely to oppose new construction. Although a change in land use may be appropriate for these properties due to the arrival of the Expo Line, the fact that wealthier residential blocks nearby were left untouched speaks to the continued political clout of Los Angeles’ homeowners. This is perhaps best highlighted by the Westwood/Rancho Park Station, which is surrounded on all sides by million-dollar houses, and was more-or-less ignored by the Expo TNP.

All of which makes me want to renew my call to shut down or otherwise reduce service to under-performing stations along the line. If the locals are not going to allow appropriate development in these choice areas, then these stations shouldn’t slow riders traveling from the dense downtowns on either end.

Boston was the first city in America to have an underground subway, an effort to relieve congestion on the crowded downtown streets and avoid weather-related delays to transit. The history of the Boston “T” railway, along with New York’s system, was covered in depth in Doug Most’s The Race Underground: Boston, New York, and the Incredible Rivalry That Built America’s First Subway, which I reviewed in 2014.

Now PBS American Experience has released a documentary on the Boston subway story, based on Most’s book. It’s an engaging film that documents the amazing electric motor innovations by Frank Sprague, a disciple of Thomas Edison, and the bruising political and construction battles to actually build the line in the heart of downtown Boston.

You can watch the documentary below or via American Experience.

If there’s one local land use policy most to blame for constricting transit-oriented development, killing the walkability of neighborhoods, adding to traffic, and encouraging sprawl, it’s excessive parking requirements.

If there’s one local land use policy most to blame for constricting transit-oriented development, killing the walkability of neighborhoods, adding to traffic, and encouraging sprawl, it’s excessive parking requirements.

How so? High parking requirements add tremendous costs to new developments, which get passed on to renters and home buyers. The extra parking stalls simultaneously limit how big a building most developers can build, which limits the number of units and therefore the available supply to stabilize prices.

High parking requirements also encourage driving, which hurts walkability and adds to the traffic. And they represent a waste of space, dedicating more land to asphalt than houses, stores, and offices, which encourages more development out in sprawl zones.

So why do local governments require so much of it? Simply put: ignorance and fear. Ignorance of how much parking is actually needed (most parking requirements come from boilerplate planning texts with no relationship to actual demand), and fear that there won’t be enough parking if government doesn’t require it.

My dislike for parking requirements is why I’m happy to help promote an upcoming conference at Los Angeles City Hall on parking policy reform options, on Tuesday May 16th. The event is being organized by the nonprofit Council of Infill Builders and Los Angeles City Councilmember Jose Huizar.

Seleta Reynolds, general manager of the L.A. Department of Transportation, will provide the keynote, and a panel of experts will discuss parking reform options for the various cities and county of Los Angeles. Finally, the event will feature the release of the new report “Wasted Spaces” from the Council of Infill Builders with policy recommendations for L.A.

You can see the conference agenda for more details. Register to attend soon, as space is limited in the room atop City Hall.