Scott Wiener, San Francisco’s state senator elected in 2016, has already authored some landmark legislation on housing (SB 35), and he’s co-authored other measures related to transportation and leading the state resistance to the Trump administration.

Scott Wiener, San Francisco’s state senator elected in 2016, has already authored some landmark legislation on housing (SB 35), and he’s co-authored other measures related to transportation and leading the state resistance to the Trump administration.

I’ll be interviewing him tonight on City Visions at 7pm to discuss these issues and what Sen. Wiener sees on tap legislatively and politically for the state in 2018. Tune in on KALW 91.7 FM in the San Francisco Bay Area or stream it live. We welcome your questions and comments!

Riding transit can be a great way to be a part of your community, as you get a chance to mingle with people from all walks of life instead of traveling in an isolated vehicle. But humanity isn’t always grand, and sometimes transit can expose you to some obnoxious behavior.

When that happens, just imagine you’re traveling with your own Spock, from this classic scene of Spock and Captain Kirk time traveling to 1980s California in Star Trek 4:

So says a new study by researchers Jesper Ingvardson and Otto Nielsen from the Technical University of Denmark, as reported by The City Fix:

Ingvardson and Nielsen compare 86 metro, light rail transit (LRT) and bus rapid transit (BRT) corridors using several variables: travel time savings, increase in demand from riders, modal shift, and land use and urban development changes. In some cases, the much more economical BRTs matched and even outperformed rail.

The key for buses to match or exceed all of these major benefits of rail is to have “buses done right.” That means bus rapid transit in its own dedicated lanes, with fast boarding and frequent service.

The benefits for transit advocates and the public are huge: bus rapid transit is far cheaper than rail (often 1/5 the price) and can get built much more quickly (sometimes in 1/5 the years).

To be sure, rail is appropriate in densely populated environments and travel corridors. But most cities in the United States have many more moderate-density corridors than high-density ones. In these areas, the case for true bus rapid transit is looking more and more like a no-brainer.

Richard Thaler, one of the founders of modern behavioral economics, just won the 2017 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences. His research holds some interesting lessons for transportation planners trying to reduce traffic. Specifically, it highlights why people may be averse to policies that charge drivers more for peak-hour driving.

The goal of “congestion pricing” is to alleviate traffic and encourage more transit usage, walking and biking. As I described last week, it tolls drivers during peak times for entering city centers. It’s an important strategy for cities like Los Angeles that need to reduce traffic to increase mobility, while funding alternatives to driving with the revenue.

Yet Thaler’s research is a cautionary tale for congestion pricing. He describes the “endowment effect,” which is closely related to loss aversion. Basically, people try to avoid losses in their well-being, money, and so forth, much more (at least rationally so) than they try to pursue gains. As Vox.com explained:

The endowment effect helps explain why businesses don’t engage in rational behavior if it’s likely to enrage their customers. Take, for instance, concert venues that know their events are likely to sell out quickly, and yet do not jack up ticket prices to hundreds or thousands of dollars to control the demand. Because jacking up the price would entail taking away something people are used to — reasonable ticket prices — it prompts a strong feeling of repulsion and injustice, which can lead to consumers turning on businesses and hurting them more than raising prices would help.

How does this apply to congestion pricing? Simply put, if drivers are used to driving somewhere for free, and now they’re being charged, the endowment effect indicates that many of them are going to be upset (potentially irrationally so) and react against the policy makers who are now charging them.

So what can be done to counter it? Well, first of all, policy makers can ensure that drivers have options to avoid the charges, such as the ability to drive off-peak to avoid getting charged as well as having access to easy transit, walking or biking alternatives. Second, policy makers can present the pricing arrangement as a temporary pilot, in order to give drivers the opportunity to see the “gains” from such an arrangement through decreased traffic and travel times.

Either way, congestion pricing may prove to be a tough sell in Los Angeles, albeit a needed one.

The impact of ride-hailing companies like Uber and Lyft on transit ridership hasn’t been clear. Anecdotes and personal hunch suggests that they’ve hurt transit ridership nationwide and increased driving miles.

The impact of ride-hailing companies like Uber and Lyft on transit ridership hasn’t been clear. Anecdotes and personal hunch suggests that they’ve hurt transit ridership nationwide and increased driving miles.

Now we finally have a study to document that impact, courtesy of UC Davis’s Institute of Transportation Studies. As the San Francisco Chronicle summarized:

•Urban ride-hailing passengers decreased their use of public transit by 6 percent. Bus and light rail service were both used less often by Uber and Lyft riders, while commuter rail saw a 3 percent bump in usage.

•Many ride-hailed trips (49 to 61 percent) would have not been made or would have occurred via walking, biking or transit.

“Ride-hailing is currently likely to contribute to growth in vehicle miles traveled in the major cities represented in this study,” the report authors wrote.

This is an important step in understanding the cause of falling transit ridership. It’s also an argument in favor of policy action, like congestion pricing and switching from the gas tax to a mileage fee to discourage extra car trips.

But fundamentally, transit agencies still need to do what they can to improve ridership, which includes requiring more development adjacent to transit stops and re-evaluating their fare structure and service network.

Ever wonder why L.A. has taken so long to get robust rail transit, compared to other American cities like Atlanta, Washington D.C., or the San Francisco Bay Area? Any questions about why the city has rail in some places but not in others? Or the status of planned rail lines?

Ever wonder why L.A. has taken so long to get robust rail transit, compared to other American cities like Atlanta, Washington D.C., or the San Francisco Bay Area? Any questions about why the city has rail in some places but not in others? Or the status of planned rail lines?

You can ask me these and any other L.A. rail questions today on-line from 1:30 to 2:30pm. As part of its “transportation week”, Curbed L.A. is hosting a live chat with me. Some interesting questions are already on the chat web page, so feel free to add yours in advance or during the live session.

Hope you can join. And for a deeper dive on Los Angeles rail transit history, check out my book Railtown from U.C. Press.

The story is fairly well known: Los Angeles used to have one of the biggest public transportation systems in the world, with the Red and Yellow trolley cars delivering people from their “streetcar subdivision” homes to the city center and beyond. But the automobile — and not an automaker conspiracy — proved more appealing to Angelenos than sitting on a crowded, tardy, and unreliable streetcar. And thus the system fell into disrepair, disuse, and extinction.

The story is fairly well known: Los Angeles used to have one of the biggest public transportation systems in the world, with the Red and Yellow trolley cars delivering people from their “streetcar subdivision” homes to the city center and beyond. But the automobile — and not an automaker conspiracy — proved more appealing to Angelenos than sitting on a crowded, tardy, and unreliable streetcar. And thus the system fell into disrepair, disuse, and extinction.

Curbed LA delves back into this history and helps dispel the myth that car companies undid the streetcars. In the piece, reporter Elijah Chiland asked me if anything could have been done to avoid abandoning the trolley streetcars in favor of the short-lived functionality of the automobile:

Elkind says the streetcar still could have been saved, but that “it would have taken some imagination and foresight on the part of the public to think, ‘what if we did subsidize this transit service? We might be able to address some of the problems that we have and make it a better service.'”

For whatever reason, that just didn’t happen. “The leadership wasn’t there and the foresight wasn’t there,” he says.

In the matter of the streetcar’s untimely demise, we Angelenos may have no one to blame but ourselves.

Chiland asked a good question. Certainly many European cities decided not to ditch their streetcars during the post-war era, and they are now better off for it (although most American cities did abandon theirs, from Washington DC to the Bay Area).

Chiland asked a good question. Certainly many European cities decided not to ditch their streetcars during the post-war era, and they are now better off for it (although most American cities did abandon theirs, from Washington DC to the Bay Area).

But during a brief moment in the history of the rise of the automobile, Downtown Los Angeles officials experimented with ditching the automobile during peak hours. In the 1920s, they issued a short-lived ban on parking during certain daytime hours. But the public (and downtown business leaders) rebelled, and the policy was scrapped. During that time though when car parking was banned, streetcars evidently regained their prominence downtown and avoided the sometimes 60-minute delays caused by car traffic halting the trains, which had undermined rail service and contributed to its unpopularity.

So local policies on critical automobile issues like parking, as well as support for auto-oriented infrastructure, ultimately sealed the streetcars fate.

It’s too bad, because now Los Angeles is trying to rebuild much of that streetcar system at a huge cost, while also trying to retrofit existing car-oriented neighborhoods into more compact, walkable development. It’s hard to undo what’s already been done, but a growing population and demand for new housing presents the region with an opportunity to correct some of these past mistakes.

Joel Kotkin and Wendell Cox recently tried to explain falling transit ridership in the Orange County Register, offering an inaccurate diagnosis of the cause, along with counter-productive, infeasible solutions.

First, the problem of falling transit ridership they describe is definitely real and pressing:

[S]ince 1990, transit’s work trip market share has dropped from 5.6 percent to 5.1 percent. MTA system ridership stands at least 15 percent below 1985 levels, when there was only bus service, and the population of Los Angeles County was about 20 percent lower. In some places, like Orange County, the fall has been even more precipitous, down 30 percent since 2008.

Yet they attribute falling ridership solely to the sprawling “urban form” of Southern California, which they argue is too spread out to support much transit, particularly rail. But this factor doesn’t necessarily explain why transit ridership is down nationwide. While researchers are still examining it, it is likely due to a combination of larger trends such as low gas prices, more congestion from increasing vehicle miles traveled (which slows down buses), higher fares and decreasing service, and the rise of venture capital-subsidized Uber and Lyft.

Still, Cox and Kotkin are right that Los Angeles is generally a “spread out” city, with the downtown area employing just two percent of the region’s workers (although it has pockets of density to rival any eastern city, such as the Wilshire Corridor). As a result, transit — particularly rail — has a tougher time attracting sufficient riders in low-density areas. This decentralized pattern has also been the cause of the region’s severe traffic (and air quality) problems.

But then Kotkin and Cox — pardon the expression — go off the rails. In their view, Los Angeles’ sprawling urban form is the result of collective individual preferences, as expressed in a free market for housing — and not public policy interventions. They see the single-family home with a two-car garage and a driving commute as the dream that virtually every American wants to achieve.

According to this logic, any effort that makes it harder to live in suburban-type housing must be a form of social engineering by heavy-handed government officials or greedy developers, trampling the will of the home buyer. They use expressions to characterize this dynamic like “a growing fixation among planners and developers” and “the urbanist fantasies of planners, politicians and developers.”

And yet the evidence does not support their vision of the ideal housing situation. Land use is in fact one of the most regulated sectors of the economy, not the perfect expression of free market demand. The lack of density in economically thriving parts of Los Angeles has little to do with people’s aversion to “stack-and-pack” housing, as Kotkin and Cox term it. It is instead largely the result of highly restrictive zoning practices that prevent new multifamily housing near transit and jobs from getting built.

And yet the evidence does not support their vision of the ideal housing situation. Land use is in fact one of the most regulated sectors of the economy, not the perfect expression of free market demand. The lack of density in economically thriving parts of Los Angeles has little to do with people’s aversion to “stack-and-pack” housing, as Kotkin and Cox term it. It is instead largely the result of highly restrictive zoning practices that prevent new multifamily housing near transit and jobs from getting built.

Similarly, the suburban homes in communities far from job centers, like in the Inland Empire, are made feasible by public policies that subsidize the automobile and its related infrastructure. Basically, most home buyers have little choice: if you’re raising a young family, you’re likely priced out of expensive, job-rich neighborhoods due to the lack of new housing supply there. And you’re unlikely to want to live in high-crime urban areas with underperforming schools. As a result, your only option is cheap land in a far-flung suburban area.

Now to be sure, a sizeable percentage of home-buyers do want to live in suburban-style homes, but there are limits to that demand. In survey after survey, consumers report their strong preference for walkable neighborhoods and housing in proximity to jobs and schools. For example, a 2015 survey showed that 68% of Bay Area residents place a high or top priority on walkability for a home, while 50% want convenient access to transit from their home.

Furthermore, demographics run against the trend of suburbanization that Kotkin and Cox favor. Between 1970 and 2012, the share of households with married couples with children under 18 decreased by half, from 40 percent to 20 percent. Over that same period, the average number of people per household also declined from 3.1 to 2.6. To put it simply, these are not trends that argue for building more single-family, far-flung homes.

In short, Kotkin and Cox miss the policy support for decentralization and sprawl that contributes to the transit ridership problem. To reverse these negative ridership trends, policy makers should instead be lifting the barriers to new housing and commercial development near transit. They should also provide equitable funding for non-automobile infrastructure, such as bike lanes, pedestrian walkways, and transit. And they should price the externalities created by long-distance car commutes, such as through gas taxes that pay for the pollution and congestion pricing on crowded freeways and arterials.

But Kotkin and Cox instead advocate for unworkable solutions to address the ridership and mobility challenges. Specifically, they want more people to work from home, more Ubers and Lyfts, and a Hail Mary from autonomous vehicles to shuttle everyone around in robot cars.

First, working from home is not a viable long-term solution for many workers, given that only a certain percentage of jobs allow for this kind of arrangement, specifically office workers. Second, relying on Ubers and Lyfts, as well as autonomous vehicles, will only increase overall vehicle miles traveled in the region. This means more traffic overall, more lost open space, and more air pollution — all counter-productive results. And even if autonomous vehicles temporarily speed up freeway traffic, history has shown us time and again that increased road capacity only induces more car travel to fill it.

While Kotkin and Cox decry the worsening congestion from more “densification,” more compact neighborhoods actually decrease overall driving miles, even if congestion might worsen in the immediate areas. Along with sensible local parking policies, congestion pricing, and enhanced investments in transit, biking, and pedestrian infrastructure, the real solution is to create viable, compact neighborhoods close to jobs and transit, without forcing residents to be car dependent.

More of these transit-friendly communities would meet market demand and provide an alternatives for the growing demographic that is sick of business-as-usual housing options. It would also boost ridership on our buses and trains. But more of the status quo, as Kotkin and Cox propose, simply doubles down on failed policies that created the region’s mobility, economic, and quality-of-life problems in the first place.

California local governments have long been stymied in efforts to raise taxes for basic infrastructure and services by California’s constitution. Two voter-approved constitutional amendments, Propositions 13 and 218, require that any new local “special tax” (i.e. for a specific purpose and not for general revenue for the government) receive two-thirds voter approval.

California local governments have long been stymied in efforts to raise taxes for basic infrastructure and services by California’s constitution. Two voter-approved constitutional amendments, Propositions 13 and 218, require that any new local “special tax” (i.e. for a specific purpose and not for general revenue for the government) receive two-thirds voter approval.

It’s a high bar that has made it more difficult for locals to fund transit, parks, and other specific needs. And when local governments do secure two-thirds support, the initiatives are often the result of promises to spread the revenue around to make as many voters happy as possible, rather than prioritizing efforts to spend the money as cost-effectively as possible (the two are not always synonymous).

So it’s potentially a big deal that the California Supreme Court ruled today that any city or county “general tax” measure (i.e. not one for a specific purpose like transit or parks) that is placed on the ballot via the initiative process (a petition signed by 15 percent of the city’s voters) is not bound by Prop 218 requirements. Because the same logic could easily apply to “special taxes” that otherwise require a two-thirds supermajority, it potentially opens the door for much easier approval of any new tax measure placed by special interests.

The facts of California Cannabis Coalition vs. City of Upland involve a nonprofit that secured enough signatures to get a medical marijuana initiative on the ballot in the City of Upland. The initiative included proposed fees on new dispensaries, but the city council concluded the fees would constitute a general tax that needed to be placed on the ballot at the next general election.

The case ironically ended up being moot for these parties, as the Upland ballot measure was defeated handily by city voters. But the Supreme Court wanted to rule on the question as to whether or not Prop 13 and Prop 218 meant to restrict all local tax measures placed on the ballot, regardless of they got there — or just the ones placed on the ballot by “local governments” (i.e. the city, county or local agency).

Ultimately, the court concluded that the voter initiative power can only be limited when measures like Prop 13 or Prop 218 specifically state that they’re limiting these powers. Otherwise, they only apply to government entities like a city council or transportation agency.

The result may now be that any citizen, nonprofit or business group that wants to place a sales tax measure or fee on the ballot for something like a new school or transit line may only need a simple majority voter approval, provided they can get enough signatures for their measure. And unless barred by some other law, I gather there’s nothing stopping agency representatives or elected leaders in their individual capacities from sponsoring these campaigns in ways that essentially amount to the city, county, or agency sponsoring the measure themselves.

As an example, take a transit sales tax measure in a place like Los Angeles County. In the past, the county’s transportation agency, LA Metro, has sponsored these initiatives under their state law grant of authority, and the county supervisors have approved placing them on the ballot. Due to Prop 218, they’ve required two-thirds approval.

But now suppose an elected leader who serves on Metro, or a nonprofit or business group closely aligned with Metro, wants to place such a tax measure on the ballot. Provided they can fundraise for the signature gathering (which would be expensive in a county as large as Los Angeles), they would now only need a simple majority approval at the ballot box. In short, this decision could be transformational for local “self-help” efforts to fund badly needed infrastructure projects.

Or as Jon Coupal, head of the pro-Prop 13 Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Association tweeted after the decision, described it:

CA Supreme Court rips huge whole in Prop 13 and Prop 218. Tax hikes by special interest groups may avoid 2/3 vote protection.

— Jon Coupal (@joncoupal) August 28, 2017

At a time when California is struggling to reduce emissions from the transportation sector due to growing commutes from the lack of housing and transit near jobs, this decision could be significant for finally allowing locals the flexibility they need to fund these investments. Under California Cannabis Coalition vs. City of Upland, local government finance for a host of environmentally significant projects, from parks to transit to infill housing infrastructure, may have just gotten easier to pass.

Los Angeles County is a big place, with lots of urban centers to connect with rapid rail transit. Funding is limited for these expensive trains, despite the passage of two recent sales tax increases and two others passed in 1980 and 1990 respectively.

So why is the region spending these limited dollars on two rail lines in the mostly suburban, auto-oriented, low-density San Gabriel Valley? The issue is now front-and-center with the June approval of a $1.4 billion extension of the Foothill Gold Line light rail to Montclair.

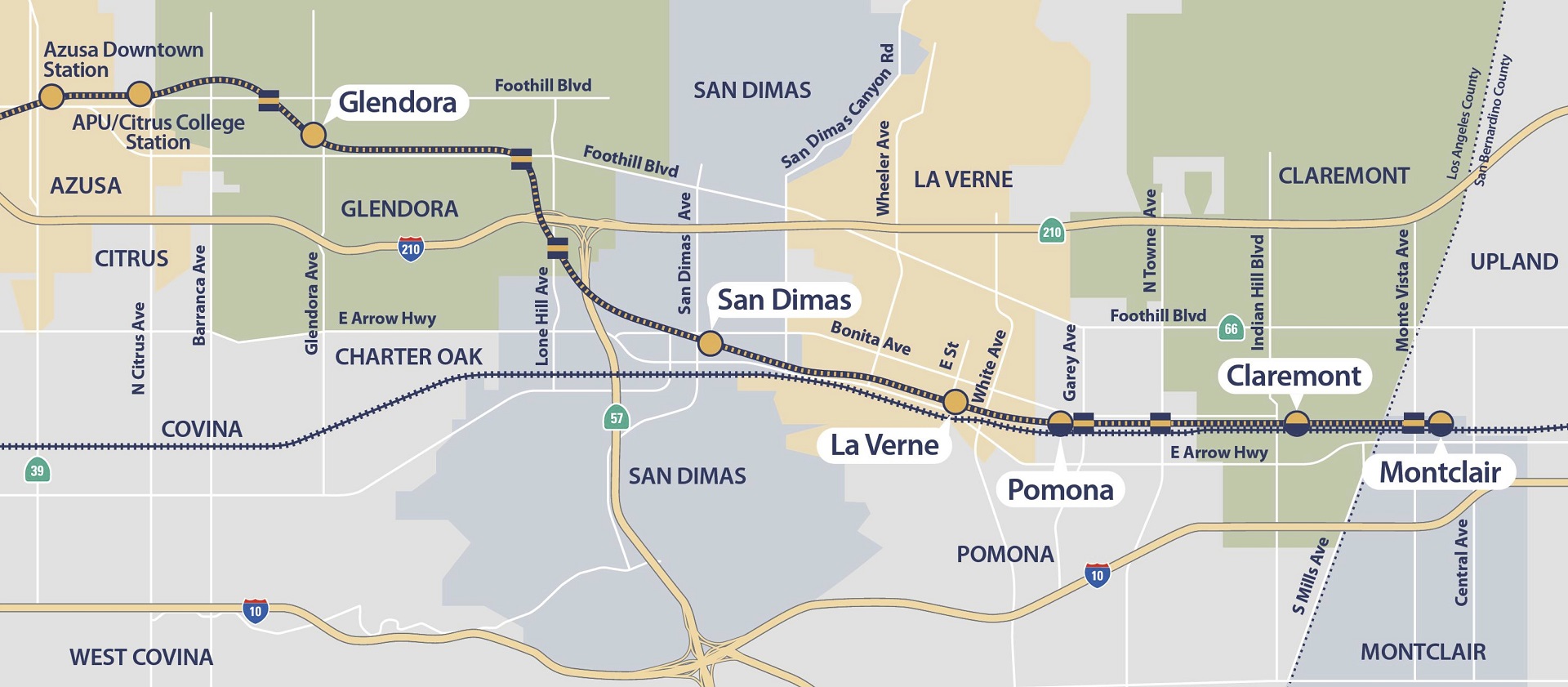

The problem is that the line dovetails with an existing Metrolink line, which is a diesel train for commuters into downtown Los Angeles. This map tells the story:

The existing Gold Line extension to Azusa already is cannibalizing nearby Metrolink service, as Urbanize LA reported:

In a report prepared for the Planning and Programming Committee, Metro staff notes that there has been a precipitous drop in ridership at a nearby station on the San Bernardino Metrolink line. In the year since the completion of the extension, which Metro calls the Gold Line Extension Phase 2A, boardings at Covina station have fallen 25 percent, despite being several miles from the Gold Line terminus at Azusa Pacific University.

Even more worrying for the future of Metrolink’s highest ridership line is the Gold Line Extension Phase 2B, which will extend the light rail line from Glendora to Claremont, and with a potential contribution from the County of San Bernardino, across the County line into Montclair. Three of the new stations, in the cities of Pomona, Claremont and Montclair, will be built in the Metrolink right-of-way and have stations directly adjacent to their commuter rail counterparts, offering perhaps an alluring alternative to the existing service. While Gold Line trains will take about 15 minutes longer to travel from Montclair to Union Station, they will be far cheaper and offer service every 7-12 minutes for most of the day.

I discussed this issue with KPCC radio recently, explaining that the reason for this extra rail service is simply politics. To secure two-thirds voter approval on the recent sales tax measures for transit, local leaders had to essentially buy off San Gabriel Valley leaders with a gold-plated rail line promise, even though the region doesn’t have the ridership to justify the expense.

That’s not to say that duplicative rail service is a bad thing by definition. If the population and job density is sufficient, two rail lines in proximity can make sense. But in this case, the density isn’t there. Metro leaders should have stood up to the San Gabriel Valley and funded a right-sized transit line. That would have most likely meant bus rapid transit and not light rail, which still would have been a big transit win for the region.

It may be too late to downsize the train route, but perhaps in the meantime Metro can develop adequate policies to ensure that San Gabriel Valley and Inland Empire leaders encourage maximum densities along the route. More dense development will not only give local residents more housing and commercial service options, it will provide more riders to minimize the losses on this unfortunate decision.