In my excitement over SB 827, the new bill that would dramatically boost badly-needed new housing in job- and transit-rich areas in California, I overlooked one potentially important source of opposition: low-income renters near transit. As I described, the bill would limit local restrictions on height, density and parking near transit. I assumed that these changes would mostly affect relatively affluent single-family home neighborhoods near transit, whose residents and allied elected officials often prevent new housing for reasons ranging from the deplorable (racism) to the understandable (fear of more traffic and related hassles).

But for renters and their advocates in existing low-income neighborhoods near major transit stops, the SB 827 approach raises different fears: eviction through displacement and gentrification. They fear the relaxed local government rules under SB 827 will prompt developers to gobble up their existing low-income buildings, evict the tenants, tear down the structures, and then build market-rate housing for people with much higher-income levels. In short, they see SB 827 putting displacement and gentrification in these transit-rich, low-income communities on steroids.

The fear is legitimate, though I believe potentially overstated, depending on the neighborhood. And it’s also something that can be mitigated, with the right policy approach. First, it’s probably overstated because development in low-income communities is not necessarily held back only by strict local zoning. For example, as UCLA scholars Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris and Tridib Banerjee described in a report examining neighborhoods around the Blue Line light rail from Downtown Los Angeles to Long Beach, low-income areas near the station stops have received virtually no investment in real estate despite sometimes very relaxed local zoning.

The problem in many of these neighborhoods is that demand is not sufficient to attract developers and capital needed to build multistory buildings. These relatively expensive structures must net high rents to justify the higher construction costs. Compounding matters, many low-income neighborhoods often require significant infrastructure upgrades to accompany any new buildings. All of these factors deter developers from investing — not the local zoning codes. Ultimately, capital will flow to the areas that promise the highest return: which means relatively affluent neighborhoods near transit will see the most construction under the SB 827 approach.

Still, those economic dynamics probably won’t by themselves allay the fears of low-income renters and their advocates. Many of the neighborhoods they care about are at risk of gentrification, which means rents could increase, higher-income residents would move in with new construction, and low-income renters forced out.

So what can be done in these situations? There’s a rich literature on the subject, but one of the best ways to mitigate these impacts is to ensure a percentage of the new homes built are available exclusively to people with low incomes. Furthermore, local residents who have been displaced or are at risk of displacement should have priority access to these new homes.

The state already has policies on the books to encourage this type of affordable housing construction, from a now-stricter regional housing needs process (which requires locals to plan and zone for affordable housing in their jurisdiction) to density bonuses for projects that incorporate more affordable units. Local governments are also free to enact their own additional policies to boost affordable housing.

These and other policies may not help all tenants facing displacement, but they would go a long way toward helping many of them — and providing access to better homes for many of them in the process. And overall, new housing near transit will benefit residents of all income levels, including low-income. It will stabilize home prices to allow more residents to live near jobs and save on transportation costs from avoiding long commutes. It will improve public health by reducing regional driving miles. It will provide high-wage construction jobs. It will reduce economic inequality and lack of access to good jobs. And it will unlock the housing that future generations will need to be able to remain in their home communities.

Ultimately, we know we need new housing in California — and lots of it to make up for decades of shortfalls. We should have policies in place to ensure low-income renters gain from this construction. But if we don’t build these homes near our transit- and job-rich areas, then where are we going to build them? SB 827 provides the clearest solution to this decades-long problem in the making. But policy makers should take care to address the concerns of low-income renters who might otherwise stand to lose under this otherwise badly needed legislation.

As I blogged yesterday, the proposed SB 827 is the first truly revolutionary approach to boosting housing in the most environmentally and economically friendly places in California.

As I blogged yesterday, the proposed SB 827 is the first truly revolutionary approach to boosting housing in the most environmentally and economically friendly places in California.

And this morning on Southern California’s KPCC radio program Airtalk, I discussed the bill with host Larry Mantle, Los Angeles City Councilmember Paul Koretz (5th District), and Mark Ryavec, president of the Venice Stakeholders Association.

The 30-minute discussion surfaced most of the predictable yet flawed objections to the bill, typically raised by homeowners and their allies:

- These new residents in housing near transit won’t really ride the transit, they’ll just add to the local congestion. Mostly false: proximity to transit is a major determinant of how likely people are to ride it. However, it is true that lower-income residents are more likely to ride. But even locating middle-income residents near transit is still better than locating them far out of the city, where they’d have long drives leading to more overall traffic and pollution, or encouraging them to gentrify existing neighborhoods due to the lack of new housing supply. And as we’ve seen in urban areas like the San Francisco Bay Area and Washington DC, professionals will ride transit if it’s convenient to their work.

- New housing near transit will only add to parking and traffic congestion in my neighborhood. Yes, possibly in the immediate areas. But if the new developments don’t oversupply and under-price parking (and SB 827 relaxes minimum parking requirements) and instead offer better transit, walking and biking access, people will be more likely to choose to avoid the traffic. And overall traffic across the region will decrease with more in-town housing, which means less pollution and regional congestion for everyone. Otherwise, the alternative is more sprawl housing.

- Transit isn’t functional in L.A. right now, so there’s no need to build more housing near it. This is to some extent a circular argument. If there’s not sufficient housing (or other development) near transit, then as a result it won’t serve many of the places people want to go. Only by encouraging that development near rail and other high-quality transit — as opposed to waiting decades for rail to go to the right places — can the system be successful. We see this all around the world with well-functioning transit lines.

The discussion and listener comments are worth hearing, because they track the typical objections to the bill’s proposals. As I wrote yesterday, SB 827 will be a huge political effort. But at the same time, it presents an opportunity to discuss the facts with the persuadable part of the electorate.

California State Senator Scott Wiener just introduced the bill I’ve probably been waiting for since I started following land use and transit in California. SB 827 would dramatically scale back local government restrictions on housing near major transit stops (see the fact sheet PDF).

These restrictions by local governments have prevented new housing from being built in precisely the job- and transit-rich locations where we need housing the most. They’ve also prevented transit from performing well, in terms of greater ridership and reduced public subsidies, as light rail lines like Expo in Los Angeles serve neighborhoods that don’t allow anything but a single-family, detached home to be built.

Overall, the effect on housing supply from these exclusionary zoning policies has caused severe environmental degradation in the state by encouraging more sprawl and traffic. And it’s caused an economic crisis of unaffordable homes and rents that has squeezed the middle class right out of the state and led to gentrification of low-income neighborhoods.

SB 827 puts a bullseye on these policies. First, among other reforms, it would remove all density limits and parking requirements on any project within a half-mile of a major transit station, defined as anything from rail to a bus stop with at least 15 minute intervals during peak commute times.

As if these changes aren’t enough, SB 827 would prevent local governments from imposing a height limit of less than 85 feet if the development is within one-quarter mile of a “high-quality transit corridor” or within one block of a major transit stop (with a few exceptions), and 55 feet if within a half-mile.

As Sen. Wiener explained in a Medium post:

California has a number of communities with strong access to transit, and we continue to invest in public transportation. Too often, however, the areas around transit lines and stops are zoned at very low densities, even limiting housing to single family homes around major transit hubs like BART, Caltrain, Muni, and LA Metro stations.

Mandating low-density housing around transit make no sense.

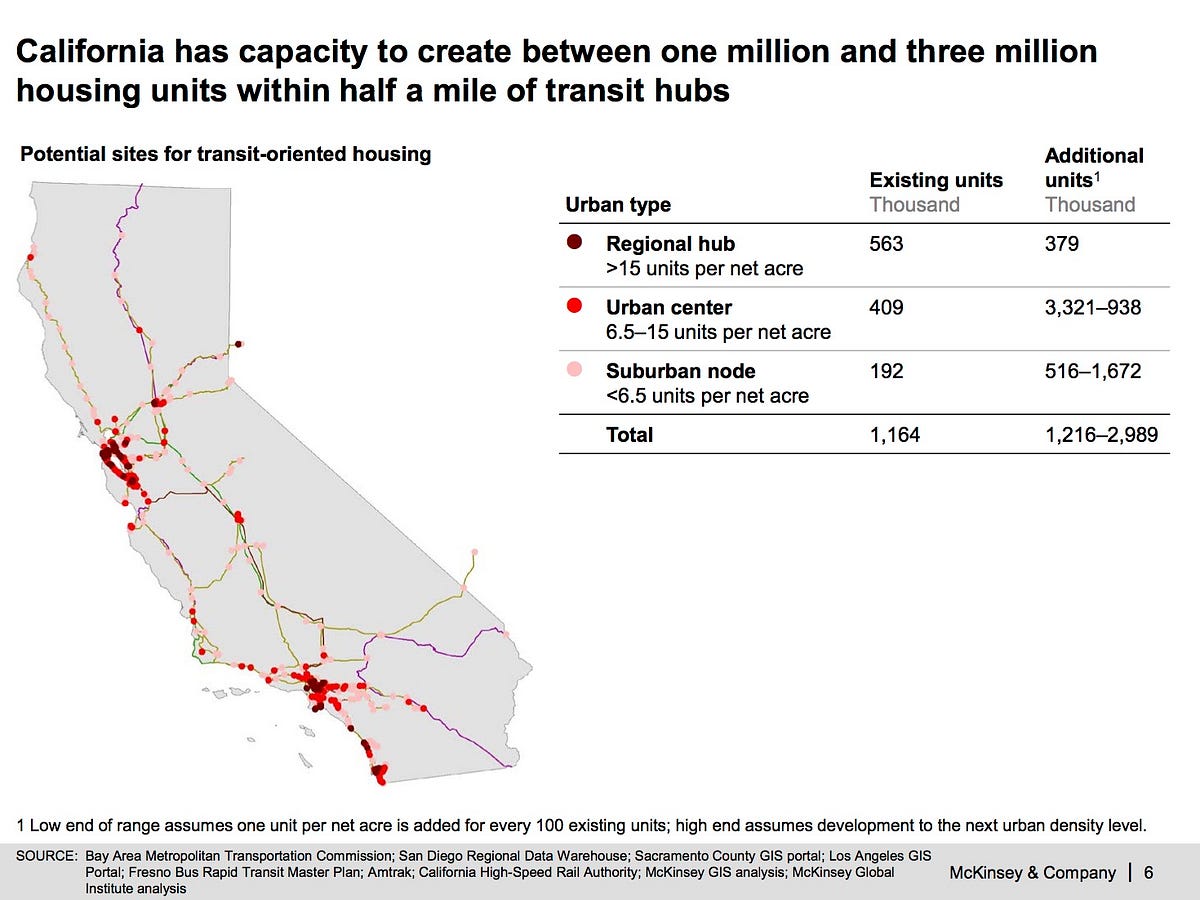

Sen. Wiener went on to cite a recent California analysis by the consulting firm McKinsey, which concluded that California could build up to three million new transit-accessible homes in these transit-rich areas:

Along these lines, our analysis at CLEE and UC Berkeley’s Terner Center in the 2017 report Right Type, Right Place found that California could achieve annual greenhouse gas reductions of 1.79 million metric tons if we built all new residential development within a few miles of major transit (not to mention additional savings if you factor in new commercial development in those areas plus reduced driving and pollution from existing residents there).

California has attempted to address this environmental and economic challenge from the multi-decade long underproduction of housing legislatively over the past few years. But most of those bills have been largely ineffectual reforms to planning or way-too-limited streamlining that only adds up to a drop in the bucket. Meanwhile, even relatively robust efforts to subsidize affordable housing are miniscule compared to the scope of the problem. SB 827 is the first one that could really, truly be a game-changer for housing and the environment.

To be sure, SB 827 faces an uphill battle to passage. Wealthy homeowners in single-family neighborhoods, along with their elected representatives and lobbyists, will be out in full force to defeat this bill. They may even have help from advocates of subsidized affordable housing, who often rely on processes to relax these exclusionary local policies as a way to gain concessions to build more affordable units. The parking requirement relaxation provision alone was already attempted back in 2011 as a standalone bill and went down to defeat in the legislature at the hands of the League of California Cities.

But on the upside, the politics in Sacramento around housing have changed in the past few years, as the scale of the problem has become more clear and as constituent groups like the “YIMBYs” have been organizing politically. That means that the bill may eventually survive to passage, albeit in a potentially stripped-down form.

If it goes down to defeat, it will be interesting to see how much support it gets. Because this issue isn’t going away, and neither are pro-housing advocates. They’ll keep coming back until California starts to take steps to address decades of terrible land use policies.

SB 827, as introduced, is the first truly significant step in that direction.

Transit advocates never really liked Elon Musk anyway. The billionaire entrepreneur behind Tesla has almost single-handedly made electric vehicles cool and desirable. But as I’ve blogged before, the cleaner cars become, the more that progress undermines one of the crucial arguments in favor of transit: that it can reduce air pollution as an alternative to dirty cars. On top of that, many transit advocates simply hate cars. So the idea that cars can now be an environmental “good” (or at least dramatically less bad for air pollution) is hard to stomach (of course, electric vehicles also include buses).

Transit advocates never really liked Elon Musk anyway. The billionaire entrepreneur behind Tesla has almost single-handedly made electric vehicles cool and desirable. But as I’ve blogged before, the cleaner cars become, the more that progress undermines one of the crucial arguments in favor of transit: that it can reduce air pollution as an alternative to dirty cars. On top of that, many transit advocates simply hate cars. So the idea that cars can now be an environmental “good” (or at least dramatically less bad for air pollution) is hard to stomach (of course, electric vehicles also include buses).

The resentment has popped up numerous times on social media and pro-transit articles, particularly around Musk’s plan for tunneling underneath Los Angeles. The plan seems to mimic existing publicly funded rail transit lines, as Curbed LA described. But instead of transit, the tunnels would feature private vehicles and larger shuttles with “between 8 and 16 passengers” that would ferry through the tunnels on sled-like “electric skates” up to 150 miles per hour.

Transit advocates largely found the vehicle-focused proposal threatening and referred to it as a waste of money that will not solve congestion and likely only induce more of it. They also noted it conveniently serves Musk’s house and office, insinuating that he’s building it to enrich himself.

The tension then boiled over when Musk recently went on a rant against transit:

“There is this premise that good things must be somehow painful. I think public transport is painful. It sucks. Why do you want to get on something with a lot of other people, that doesn’t leave where you want it to leave, doesn’t start where you want it to start, doesn’t end where you want it to end? And it doesn’t go all the time. It’s a pain in the ass. That’s why everyone doesn’t like it. And there’s like a bunch of random strangers, one of who might be a serial killer, OK, great. And so that’s why people like individualized transport, that goes where you want, when you want.”

Transit consultant and persistent Musk critic Jarrett Walker attacked in kind:

In cities, @elonmusk‘s hatred of sharing space with strangers is a luxury (or pathology) that only the rich can afford. Letting him design cities is the essence of elite projection. https://t.co/gtSVgPkfPo https://t.co/CmCpoIJ5NE

— Jarrett Walker (@humantransit) December 14, 2017

Musk responded on Twitter by calling Walker a “sanctimonious idiot.” Transit advocates in turn had Walker’s back, questioning whether Musk is an “elitist jerk” and generally amping up criticism of his urban mobility vision.

For my part, I question why transit advocates feel so threatened by Musk’s tunneling plans. First and foremost, at this point it doesn’t involve any public dollars. If Musk wants to spend his own money on an ultimately doomed plan to reduce traffic, then what’s the harm to the public? And if he’s successful, why would it be any more of a threat to transit than the current regime of publicly funded roads and highways? And isn’t there the possibility that his work could lead to innovations in tunneling and transport that might actually benefit transit and related development?

I’d also note that it’s somewhat unclear what Musk truly intends with these tunnels. They might end up being more practical for Musk’s beloved “hyperloop” idea, which in turn might be better suited for goods movement rather than people movement, given the potential danger and risk of nausea in the tubes.

Finally, I think it’s worth acknowledging that while Musk’s comments about public transit are inaccurate (not ‘everyone’ hates riding transit), he speaks for a large percentage of people, like it or not. Check out Eric Jaffe’s article on the subject from a few years ago:

Every transit advocate knows this timeless Onion headline: “98 Percent Of U.S. Commuters Favor Public Transportation For Others.” But the underlying truth that makes this line so funny also makes it a little concerning: enthusiasm for public transportation far, far outweighs the actual use of it. Last week, for instance, the American Public Transportation Association reported that 74 percent of people support more mass transit spending. But only 5 percent of commuters travel by mass transit. This support, in other words, is largely for others.

Public transit, particularly buses, do not poll well or have a very positive image among vast segments of the public, as I’m guessing a transit consultant like Walker knows. The recent nationwide ridership dip proves the point to some extent, as former transit riders are now choosing more convenient options like Uber and Lyft (or purchasing a vehicle or driving one more frequently).

For multiple reasons, we should all want public transit to succeed: it can foster more sustainable, transit-oriented development, it can provide people of all incomes with car-free travel options and therefore reduce pollution and sprawl, and it can enhance quality of life by supporting dynamic, equitable, community-oriented neighborhoods.

But many people have a negative view of transit, and not without good reason. Musk not only speaks for them, he’s speaking to them. And as long as that public attitude and its underlying causes persist, attacking Musk is at best a waste of time and at worst a failure to address some core challenges facing transit.

In my 2014 book Railtown, I covered the sad saga of Los Angeles rail transit planners’ failed attempt to bring rail to LAX (Los Angeles International Airport). While local conspiracy theorists argued that the taxi industry had scuttled the plan, the reality was that the region was running out of money for rail anyway and lacked consensus on the best route to the airport.

But transit officials at the time also cited resistance from airport officials, as I described in the book:

Many local leaders blamed the airport for the impasse, arguing that airport leaders should have been willing to contribute funds for the extension. “If [the airport] had used passenger facility funds to meet the line, we would have gone there and made it happen,” said [transportation commissioner Jacki] Bacharach. “But we never got help from the airport.” According to Ruth Galanter, who represented the area at the Los Angeles City Council, airport officials cited a federal law that prevented airport revenues from funding anything other than airport improvements. “The airlines said, ‘No way. The people using the Green Line have nothing to do with the airport, so you can’t take this money.’ If Bradley had been around for another ten years, he probably could have worked out a compromise.”

I thought of that history when I saw today’s news in the San Francisco Chronicle that airports across the country are losing money from lost fee revenue with the advent of Uber and Lyft:

Travelers’ changing habits, in fact, have begun to shake the airports’ financial underpinnings. Fewer people are parking cars at airports, using taxis or renting cars, according to a recent report from the National Academies Press.

Those trends are hurting airports, which depend on fees from parking lots, rental-car companies and taxis as their biggest source of revenue other than the fees paid by the airlines. The money they collect from ride-hailing services does not compensate for the lower revenues from the other sources.

While LAX officials denied trying to shoot down a rail connection in the 1990s, this article makes it clear that rail transit connections are not exactly in their financial interest.

In the end, LAX is about to get a rail connection from the under-construction Crenshaw Line, which will connect to a parking lot nearby and an eventual people mover around the airport. But it comes a generation after a failed effort in the early 1990s, with the airport’s economic interest likely an important factor.

San Francisco and Los Angeles are both building subways below their downtown cores. And now both cities’ projects are over-budget and late. As Matier & Ross report in the San Francisco Chronicle:

San Francisco’s already behind-schedule Central Subway won’t be completed until 2021, more than a year later than the city insists the line will be ready, according to a new report by the big dig’s main contractor.

Construction giant Tutor Perini Corp. also says the $1.6 billion project is running tens of millions of dollars over budget.

Adding insult to injury, the former head of the agency that oversaw construction of the Transbay Transit Center, which went horribly over budget, is apparently lobbying the city for more money for Tutor Perini. The delay means the line won’t be able to serve the new Golden State Warriors arena for the first two seasons. For their part, city officials seem to think the contractor is bluffing to get more money. Either way, it’s not a good sign.

Meanwhile, in Los Angeles, the downtown regional connector light rail line is also in trouble, as Laura Nelson reports in the Los Angeles Times. The new opening date is now December 2021, a year later than the agency’s original target date of December 2020. Its $1.75-billion budget is now 28% higher than originally forecast.

Residents in these two major cities are now spending a better part of a decade watching these relatively short rail lines get built, at increasing taxpayer expense. While I’m sympathetic to the challenge of building under old urban environments, I wonder how much of these challenges should have been foreseen. It’s almost a joke at this point that elected officials over-promise on cost and timelines to sell new rail lines at the outset. But it would be nice to see those those promises actually come true for once, especially for transit projects as important as these.

Some longtime rail opponents made an appearance in the Los Angeles Times op-ed pages last month, with a bus-only solution to recent transit ridership woes. James Moore from USC teamed up with former Southern California Rapid Transit District chief financial officer Tom Rubin to blame falling transit ridership on L.A. Metro’s lack of investment in buses compared to rail.

Moore and Rubin went to lengths to extol the benefits of the now-expired 1990s consent decree to settle a lawsuit against L.A. Metro by the Bus Riders Union. The settlement decree forced L.A. Metro to privilege spending on buses over rail:

The settlement allowed Metro to build all the rail it could afford, so long as specific bus service improvements were made too. Those improvements included reducing fares, increasing service on existing lines, establishing new lines, replacing old buses and keeping the fleet clean. Lo and behold, while the decree was in force L.A.’s transit ridership rose by 36%. When Metro was no longer bound by the settlement, it refocused its efforts almost exclusively on new rail projects. The quality of bus service began declining in almost every way measurable, and overall ridership again fell.

Moore and Rubin’s 2017 op-ed hasn’t actually changed much since their 2008 version in the same paper. But their claim that the consent decree boosted L.A.’s transit ridership by 36% sounds different from the 2008 op-ed. In that original piece, they acknowledged that the ridership boost during the consent decree also included rail riders, given the new lines being unveiled at the same time:

Over the next 11 years, [L.A. Metro] added buses, started new lines and held fares in check to improve the country’s most overcrowded bus system. As a result, users of public transit gradually started to increase again. Yes, some chose the Blue, Red, Green and new Gold rail lines, but the majority of riders returned to buses.

“Gradually started to increase” in 2008 doesn’t seem to match their 20017 claim of a 36% boost. Meanwhile, Bus Riders Union estimates of ridership during the consent decree years was evidently 1% per year increase, per the LA Weekly in a 2005 article. That’s not much to get excited about, given the scale of the ridership problem and the amount of money L.A. Metro spent on consent decree compliance.

I certainly agree that lower bus fares can mean more ridership, and I support improved bus service. But the idea that the consent decree was a big ridership win seems like revisionist history. More importantly, Moore and Rubin’s arguments fail to put the L.A. transit ridership problem into the national context it deserves. With low gas prices and a booming economy, plus the impact of Uber and Lyft, transit ridership decreases are happening everywhere. This isn’t just about L.A. Metro’s decision to build a lot of rail.

A true response to the challenge involves multiple solutions, of which better bus service and lower fares are just one arrow in the quiver. More dense development around transit and congestion pricing also need to be in the mix, for example. Focusing only on ideologically motivated solutions, introduced regardless of context, is less likely to be an effective approach to tackling the problem.

It’s taken a long time, but California finally is ready to make a significant change to speed environmental review for new transit and infill projects. The Governor’s Office of Planning & Research (OPR) announced on Monday that a compromise has been reached to implement SB 743 (Steinberg, 2013), a law that made major amendments to the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), the state’s law governing environmental review of new projects.

Back in 2013, the legislature passed SB 743 to change how infill projects undergo environmental review. Under the traditional regime, project proponents had to measure transportation impacts by how much the project slowed car traffic in the immediate area. The perverse result was mitigation measures to privilege automobile traffic, like street widening or stoplights for rail transit in urban environments or new roadways over bike lanes in sprawl areas.

But the true transportation impacts are on overall regional driving miles. An urban infill project may create more traffic locally but can greatly reduce regional traffic overall by locating people within walking or biking distance of jobs and services. Meanwhile, a sprawl project may have no immediate traffic impacts, but it typically dumps a huge amount of cars on regional highways, leading to more traffic and air pollution. As a result, the switch from the “level of service” (auto delay) metric to “vehicle miles traveled (VMT)” made the most sense. Most infill projects are exempted entirely under this metric, while sprawl projects would have to mitigate their impacts on regional traffic.

But OPR’s implementing guidelines with this change were held up by highway interests and their government allies, who don’t want the law to apply to highways. You can probably see why: highways are designed to do one thing only — induce more driving. And that would score poorly under this change to CEQA.

State leaders finally reached a compromise this month: the new guidelines could apply statewide to all projects (something only suggested by the statute), but new highway projects can still use the old “level of service” metric, at the discretion of the lead agency (see the PDF of the guidelines for more details at p. 77).

It’s an unfortunate but probably necessary concession to powerful highway interests. Even though freeways have consistently failed to live up to their promise of fast travel at all times, and instead brought more traffic, sprawl and air pollution to the state, many California leaders are still wedded to this infrastructure investment.

My hope is that the compromise won’t actually mean that much new highway expansion in the state. First, California isn’t planning to build a lot of new highways, outside of the ill-advised “high desert corridor” project in northern Los Angeles County. Second, even for new highway projects, CEQA’s required air quality review may necessitate an analysis of (and mitigation for) increased driving miles.

Either way, smart growth advocates can at least celebrate the good news that CEQA will finally be in harmony with the state’s other climate goals on infill development, transit, and other active transportation modes.

The guidelines though still need to be finalized by the state’s Natural Resources Agency, which will take additional months. I’ll stay tuned in case anything changes with the proposal during this time.

California is on track to meet its 2020 climate change goals, to reduce emissions by that year back to 1990 levels. Much of that success is due to the economic recession back in 2008 and significant progress reducing emissions from the electricity sector, due to the growth in renewables.

But the state is lagging in one key respect: transportation emissions. Bloomberg reported on the emissions data compiled by the nonpartisan research institute Next 10:

But the state is lagging in one key respect: transportation emissions. Bloomberg reported on the emissions data compiled by the nonpartisan research institute Next 10:

In 2015, the most recent year for which data are available, the state’s greenhouse gas emissions dropped at less than half the rate of the previous year, according to an August report from the San Francisco-based nonprofit Next 10. Low gas prices and a lack of affordable housing prompted more driving and contributed to a 3.1 percent increase in exhaust from cars, buses, and trucks, the report says. Census data show that more than 635,000 California workers had commutes of 90 minutes or more in 2015, a 40 percent jump from 2010.

The solutions are urgent: we need to reduce driving miles by building all of our new housing (an estimated 180,000 units needed per year) near transit, and we need to electrify our existing vehicle fleet and add in biofuels and hydrogen where appropriate. Otherwise, the state will not be as successful in meeting its much more aggressive climate goals for 2030, with a 40% reduction below 1990 levels called for that year.

First, advocate for a multi-billion transit line that will serve your home neighborhood. Then once it’s built, make sure nobody else can move to your neighborhood to take advantage of the taxpayer-funded transit line. It’s a classic bait-and-switch, and it’s happening now along the Expo Line in West L.A.

What’s at stake is an already-watered down city plan for rezoning Expo Line stations areas. The city’s “Exposition Corridor Transit Neighborhood Plan,” while rezoning some station-adjacent areas for higher density, still leaves a whopping 87% of the area, including most single-family neighborhoods, unchanged, and with too-high parking requirements to boot.

But this weak plan is still too much for Los Angeles City Councilmember Paul Koretz and his homeowner allies, including an exclusionary group of wealthy homeowners assembled under the name “Fix The City.” They oppose even these modest changes to land use in the transit-rich area. Essentially, they’ll get the financial and quality-of-life benefit of the Expo Line, while working to ensure no one else does.

As Laura Nelson details in the Los Angeles Times:

Koretz told the Planning Commission this month that the areas surrounding three Expo Line stations in his district “simply cannot support” more density without improvements to streets and other public infrastructure.

It’s a view shared by advocates from Fix the City, a group that has previously sued Los Angeles over development in Hollywood and has challenged the city’s sweeping transportation plan that calls for hundreds of bicycle- and bus-only lanes by 2035.

“It’s like when you buy a new appliance, you’d better read the fine print,” said Laura Lake, a Westwood resident and Fix the City board member. “This is not addressing the problems that it claims to be addressing.”

If Koretz and his allies have their way, their homeowner property values will go up with the transit access, but taxpayers around the region have to continue subsidizing the line even more because neighbors are not allowing more people to ride it. And to boot, they will keep regional traffic a mess by not allowing more people to live within an easy walk or bike ride of all the jobs near their neighborhood. Essentially, they force everyone else into long commutes while keeping housing prices high — an ongoing environmental and economic nightmare.

Thankfully there are others mobilizing against these homeowner interest groups, such as Abundant Housing L.A. But two things need to happen now: first, the Expo neighborhood plan needs serious strengthening, including elimination of parking requirements and an end to single-family home zoning near transit stops. Second, L.A. Metro needs to hold the hammer over these homeowners by threatening to curtail transit service to the area. I see no reason why taxpayers should continue to support service to an area that won’t do its part to boost ridership on the line.

Single-family zoning near transit is an idea that should have died long ago. It has no place in a bustling, modern, transit-rich environment like West L.A. The Expo Line bait-and-switch must end.