It was only a matter of time. Once Republicans swept the election in November, they were likely to start using federal transportation funds to kill urban transportation projects. Not only do Republicans tend to dislike public funding for any form of non-car-related transportation, but most transit systems are in Democratic urban strongholds, giving Republicans little incentive to spend dollars there.

California’s high speed rail project is apparently the first up in their crosshairs. Even though state voters approved the system in 2008 and have been largely funding it themselves, what little dollars from the federal government to support the system are now in jeopardy.

Case in point: right before this past holiday weekend, congressional Republicans succeeded in getting the new transportation secretary, Elaine Chao, to effectively kill funding for Caltrain electrification.

The Caltrain project actually has little to do with high speed rail, although eventually high speed rail could use the upgraded tracks to serve San Francisco. But in the meantime, electrifying the popular commuter rail between Silicon Valley and San Francisco would decrease travel times and air pollution and increase capacity, providing a huge benefit to the technology breadbasket of the country, while generating jobs from contractors and suppliers around the country.

The federal government under Obama had already agreed in principle to help fund the line with a $647 million transportation grant, with high speed rail funds used to help support the state’s contribution to the project. But then 13 Republican members of congress wrote Chao a letter demanding that the grant be halted until a full audit of the high speed rail system could occur.

Chao complied on Friday, proving that the administration is keen to play politics with transportation dollars and keep them away from urban areas.

Perhaps most galling for Bay Area residents, Congressman Kevin McCarthy, a leading critic of high speed rail from Bakersfield, wrote an op-ed in the San Francisco Chronicle full of hypocrisy:

We should work to unwind the messy and unworkable high-speed rail project, and instead try to direct more funds to modernizing needed transit and infrastructure projects — up and down the valley and the coast, in and out of downtown Los Angeles, and along Bay Area commuter corridors.

Which is of course exactly what the high speed rail money would have done with this project.

Meanwhile, the Bay Area’s business community had tried to lobby McCarthy not to hold up the funds, at a fundraiser on February 9th. As Matier and Ross report in the San Francisco Chronicle:

“He [McCarthy] said he supported electrification of Caltrain, but said the problem was that the $647 million was commingled with high-speed rail money and that the line would be used by high-speed rail,” said Bay Area Council President Jim Wunderman.

As for McCarthy’s argument against high-speed rail?

“Same as it has always been,” Wunderman said. “Too costly. It’s not really high-speed rail.”

The move by the feds won’t kill high speed rail though:

Dan Richard, chairman of the state’s High-Speed Rail Authority, said that if McCarthy and the other 13 California House Republicans were out to kill bullet trains, they picked the wrong target.

“The business plan allows us to stop at San Jose,” Richard said. “If McCarthy is trying to blow us up, Caltrain was collateral damage.”

But the message is clear: until Republicans lose power in Washington DC, California is on its own in funding vital transportation infrastructure like high speed rail.

The one place California should be building high speed rail immediately is between Los Angeles and San Diego. As I’ve blogged before, the two big cities are too close to fly and too painful to drive conveniently, due to traffic. That makes them perfect for high speed rail. The line would likely be the most lucrative of any in the state.

The one place California should be building high speed rail immediately is between Los Angeles and San Diego. As I’ve blogged before, the two big cities are too close to fly and too painful to drive conveniently, due to traffic. That makes them perfect for high speed rail. The line would likely be the most lucrative of any in the state.

So of course it’s slated to be the last line built in the statewide high speed rail plan. But transportation researcher Alon Levy makes a case in Voice of San Diego that the current line could be upgraded relatively inexpensively, given new federal rules that allow lighter European trains to run on U.S. tracks:

This means that the region needs to invest in electrifying the corridor from San Diego to Los Angeles, and potentially as far north as San Luis Obispo. Between San Diego and Los Angeles, the likely cost – based on the California high-speed rail electrification cost – is about $800 million.

The benefits are considerable. Electric trains emit no local pollution, while diesel is an unusually dirty fuel, contributing to Southern California’s poor air quality. New EPA rules, the Tier 4 standards, have required rail agencies in the U.S. to buy cleaner-burning diesel locomotives. The Pacific Surfliner has recently bought Tier 4-compliant locomotives, but many intercity and commuter rail routes around the country are interested in such trains, so they could likely fetch a good price by selling them now on the second-hand market. While these locomotives are cleaner than the legacy ones they replace, they are almost as heavy, and are unsuitable for a fast operation.

Levy also recommends specific track upgrades, such as running trains along I-5 to avoid Miramar Hill, which slows down the trains considerably as they wind up it. Ultimately, with these improvements, train times between the cities could clock in at less than two hours — competitive with driving even without traffic. And with full high-speed rail service, the estimated travel time would be closer to 1 hour and 20 minutes.

Local leaders in the three affected Southern California counties should act immediately to invest in these upgrades. A multi-county bond issue could probably provide the sufficient dollars, and I’m guessing it could get public support with the right campaign.

Meanwhile, the benefits for the local rail transit systems in the two cities would be immense. Passengers getting off the high-speed trains in Union Station would be more likely to hop on a Metro Rail train to Pasadena, Long Beach, Hollywood or Santa Monica, while train passengers in San Diego could take the trolley around the region, boosting ridership on both systems.

The upgrade is really a no-brainer when it comes to boosting train service. It will just take the political will and the dollars needed to finance it.

My interview on Monday night’s City Visions program on KALW radio with Dan Richard, chair of the California High Speed Rail Authority, covered a lot of ground on the status and future of the proposed system. You can listen to the audio here. Some key takeaways from my perspective:

My interview on Monday night’s City Visions program on KALW radio with Dan Richard, chair of the California High Speed Rail Authority, covered a lot of ground on the status and future of the proposed system. You can listen to the audio here. Some key takeaways from my perspective:

- A federal infrastructure spending bill next year with a new president will be critical to shoring up the existing system’s finances and allowing it to get fully built out by 2029. The current federal contribution is historically meager, compared to how much the state is contributing in tax dollars.

- The Authority will need the San Jose to Fresno section to get up and running as soon as possible to demonstrate a revenue-making, operable segment, which will lay the political foundation for more support for the system.

- The Authority and other local leaders are going to need more tools to ensure that the system does not lead to more sprawl around the stations and instead encourages more station-oriented development. Those tools could involve urban growth boundaries coupled with more funding for infill areas.

This will be a very long-term project for the state, but it’s the first high speed rail system under construction in the United States. While a fully built out train is decades away, perhaps with a big federal push next year we’ll see the first section operating soon between Silicon Valley and Fresno. That development would be transformative for the Central Valley. Overall, it’s a vital infrastructure project for the state’s residents to keep tabs on.

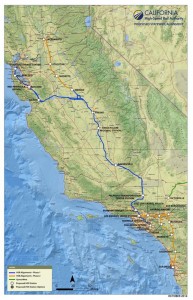

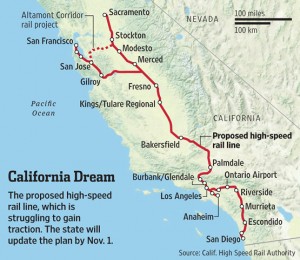

California’s high speed rail system has been moving at a low speed since voters approved a bond issue to launch it in 2008. That ballot measure authorized a bullet train from San Francisco to Los Angeles and eventually Anaheim, at speeds of 220 miles per hour and stops in Central Valley cities like Fresno and Bakersfield. The total trip time would be no more than 2 hours and 40 minutes between the two big cities, at fares less than airplane travel.

California’s high speed rail system has been moving at a low speed since voters approved a bond issue to launch it in 2008. That ballot measure authorized a bullet train from San Francisco to Los Angeles and eventually Anaheim, at speeds of 220 miles per hour and stops in Central Valley cities like Fresno and Bakersfield. The total trip time would be no more than 2 hours and 40 minutes between the two big cities, at fares less than airplane travel.

The rationale for the system is that it will provide a cheaper way to move a growing population around the state than expanding airports and highways. It will connect the relatively weak economies of the Central Valley with the prosperous coastal cities, providing an economic boost, all while enabling low-carbon transportation and promoting car-free lifestyles for communities connected to the system.

But since 2008, legal and political battles have slowed the system’s progress, as everyone from farmers in the Central Valley, wealthy homeowners in the San Francisco peninsula, and even equestrians in the hills above Burbank have fought to push the route away from their land. It’s local NIMBY politics on a statewide scale.

These legal and political challenges have in turn created funding headaches for the system. The original price tag of $40 billion ballooned to a projected $118 billion, before a revised business plan reduced it to an estimated $62 billion, as described in the 2016 business plan. Of that amount, the 2008 bond issues provides almost $10 billion, federal funds provide another $3.3 billion, and cap-and-trade funds may provide another few billion. System backers hope the rest come from private sources, but so far none have stepped up.

With strong support from the governor, the state was able to dedicate 25% of cap-and-trade auction proceeds to high speed rail construction. But the auction faces legal uncertainty going forward, due to a pending court case brought by the California Chamber of Commerce. An adverse verdict could mean that the money will halt either immediately or post 2020.

Meanwhile, the federal government has been unusually stingy with this infrastructure project. After Republicans took over Congress in the 2010 midterms, the federal dollars dried up, leaving the state to fund the project on its own. Only the 2009 stimulus provided some federal money for the train, but nowhere close to a match for the state contribution. By comparison, the federal government typically contributes 50% of the money for urban rail systems and between 90 and 100% for highways.

The funding picture has now affected the route design. The initial connections were going to be from the Central Valley to somewhere north of Los Angeles, hooking into the commuter Metrolink train to deliver passengers to Union Station in downtown Los Angeles. Now there’s not enough money to get the train through the Tehachapi mountains that separate Southern California from the Central Valley. So the initial connection will now go to San Jose from the Central Valley, with a link to the commuter Caltrain to get passengers to San Francisco. High speed rail bond money will then pay for upgrades to Caltrain and Metrolink, to prepare those systems for eventual high speed rail connections.

So with all the controversy and politics for this important project, I look forward to interviewing California High Speed Rail Authority chair Dan Richard tonight on City Visions, on NPR affiliate 91.7 FM KALW radio in San Francisco, from 7-8pm. For those out of the area, you can stream it or listen to the archived broadcast after the show here. I’ll ask Dan for more information on the funding, politics, and current construction status. And listeners are free to call in or email with questions. Hope you can tune in and ask your questions about the system’s future!

Texas, of all places, appears to be beating California in the high speed rail game. As I’ve written before, the proposed line between Dallas and Houston has all the right attributes for success, and it is on track (ahem) with private financing to be up and running by the early 2020s.

Meanwhile, California’s progress is much slower (to be completed sometime in the 2030s at best), while the funding picture grows ever murkier. The financing has recently been undermined by poor cap-and-trade auction proceeds that Governor Brown is using to backstop the lack of available federal and private dollars.

But Texas’ early success could benefit California in key ways. First, it could improve the funding and economics of California’s system. A Texas system could encourage high speed rail manufacturing in the United States. This local production would help California obtain domestically sourced (and possibly cheaper) parts and supplies, which would allow the state to comply more fully with federal funding requirements and therefore secure more such funding.

Texas’ success could also improve the politics for California. Having high speed rail in red state Texas could change congressional attitudes and achieve more bipartisan support for high speed rail in general. That dynamic could lead to more federal dollars for the system, which have been stalled since Republicans took over the House of Representatives.

Finally, Texas’ experience could potentially inspire some improvements to California’s system design. Because California’s is primarily a government-funded system, the route has to satisfy various political constituencies. But with a privately funded system, the Texas train is all about the economics, in terms of speed and service between the most populated areas. As E&E reports (paywall):

And rather than build more than a dozen stations, which would slow California’s line, Texas Central is planning on just three stations: Houston, a central stop roughly halfway between College Station and Huntsville, and Dallas.

Though historically, governments built these systems, Kelly says his company’s private financing model actually gives it the advantage.

“It’s really hard, especially on those long routes, to have fares that are high enough but don’t price everybody out of the market and still pay for the service,” he said. “But even in Amtrak, you find some profitable routes, like the Northeast Corridor.”

Given California’s challenges in attracting federal and private funding to high speed rail, the Texas example may provide important lessons that decision-makers can incorporate. Most prominently, it may involve subtracting some stations in the middle of the route.

At some point, California leaders may need a retrenchment of the system plans to address the financing issue, barring any infusion of federal or private dollars. Who would have thought that Texas may end up as a role model for California’s high speed rail?

The Dallas to Houston route looks like it may be on-line faster than California’s Madera to somewhere-near-Bakersfield segment, per Jeff Turrentine at NRDC:

The Dallas to Houston route looks like it may be on-line faster than California’s Madera to somewhere-near-Bakersfield segment, per Jeff Turrentine at NRDC:

Now, nearly 50 years after its founding, Southwest may soon face unexpected competition for its always-booked Dallas-to-Houston service. And in a telling bit of irony, this new rival has come in the form of a railway company, of all things.

After several years spent getting its legal, financial, and procedural ducks in a row, the company known as Texas Central is moving ever closer to realizing its goal of linking two of Texas’s biggest cities via high-speed bullet train. Though a few right-of-way issues still need to be cleared up, Texas Central seems on track (I know, I know; I’m sorry) to break ground on its 240-mile-long rail system in early 2017, with service scheduled to begin within the next five years. Then the nearly 50,000 Texans whom the company has identified as Dallas-to-Houston “supercommuters”—i.e., those who drive or fly between the two cities more than once a week—will have a highly attractive third option: climbing aboard sleek, swift, tricked-out trains that depart every half-hour and reach their center-city destinations in under 90 minutes.

So what’s the secret sauce that enables Texas to get moving while California plods along, aiming to finish sometime in the 2030s? Well, I’m sure it’s cheaper and easier to build in a place like Texas, with fewer environmental restrictions and a flat terrain (no Tehachapis to deal with).

But perhaps more importantly, the rail system would connect two major cities on a straight line, covering a distance that’s a bit too far to drive and pretty close to fly. In other words, it’s the sweet spot for high speed rail. And with that fast connection, private money is flowing.

Contrast that approach with California, which is zigzagging its train from Los Angeles to San Francisco in order to satisfy various political constituencies. The result is less private sector appetite to invest and a rail connection that requires significant public support and a long time horizon to build.

I’m certainly rooting for California to build high speed rail, but red state Texas may just beat California to the punch.

Yesterday we had a fascinating discussion of the respective rail transit histories of San Jose and Los Angeles at SPUR San Jose, with a bunch of high speed rail tidbits thrown in.

It was a particular pleasure to hear from Rod Diridon, who is basically the father of rail transit in Santa Clara County, from the VTA light rail line to the under-construction high speed rail (slated to come to San Jose in the next decade or so).

Some takeaways from San Jose/Santa Clara County’s rail transit history:

- County leaders achieved a 56% voter approval on a local sales tax initiative to launch rail back in the 1970s, partly in response to a prominent New York Times article calling San Jose the worst planned city in the country, partly due to the highly educated technology workers coming to the area, and mostly due to strong leadership at the local, state and federal levels.

- The local measure required public review of the system development every four years, which in practice meant a ton of outreach to the public, which in turn resulted in widespread awareness of the system and much public buy-in. Part of this process involved colorful mailers sent to everyone in the millions, which also provided good advertising and elicited more political buy-in.

- Diridon noted the importance of steady local leadership. He, Congressman Norm Mineta, and State Senator Al Alquist occupied their positions at various levels of government in the area for decades, allowing each to take ownership of the transit system and ensure that projects were built on time and on budget.

We also touched on high speed rail. Diridon chaired the High Speed Rail Authority and is a big booster. He surprised me by saying that the first segment from San Jose to somewhere around Bakersfield will make money by turning the Valley into bedroom communities. My impression is that the daily fare (up to $80 in today’s dollars, roundtrip) will be cost-prohibitive for most people living in the Valley.

In response to a question about getting rail from Union Station in Los Angeles to Palmdale, Diridon admitted that the route to Palmdale, which will add 15 minutes to the total ride, was made only because L.A. leaders like Supervisor Antonovich and Mayor Villaraigosa insisted the train stop there. Otherwise, he said, they wouldn’t have gotten the train built. It’s further evidence of the sad political compromise on the route.

In an irony though, he said the recent decision to change the route to now serve San Jose first is because of that Palmdale stop. Horse ranchers along the path from Palmdale to Burbank/San Fernando don’t want the train coming through, so they’ve created enough hassle to make the High Speed Rail Authority hold off on the Southern California section for now.

All in all, lots to learn in comparing the rail journeys of the two cities, which will one day be linked by high speed rail.

I’ve been a bit harsh on California’s high speed rail planners. It’s hard not to be: the route is gerrymandered to satisfy political interests, which has undermined its fiscal attractiveness and created a deep financial hole to build anything of use. The twisted route has also reduced its utility for residents in California’s major population centers, while adding to the construction costs.

Meanwhile, the current financial projections simply don’t anticipate enough funding to build anything but possibly a San Jose to Bakersfield connection. Last I checked, few people in California thought those cities were priorities for the state to connect, especially given that Bakersfield already has a pretty successful Amtrak connection to the Bay Area.

But in some ways, high speed rail has been unfairly victimized so far by our polarized political environment. Most rail systems, at least of the intra-city type, usually start with a local political consensus and then funding stream, which gets matched by federal support.

But in some ways, high speed rail has been unfairly victimized so far by our polarized political environment. Most rail systems, at least of the intra-city type, usually start with a local political consensus and then funding stream, which gets matched by federal support.

During the height of federal support for rail transit in the 1960s and 1970s, local and/or state governments only had to provide 20 percent of the funds, with the federal government paying an astounding 80 percent of the costs (astounding for transit — the feds routinely pay 90 or even 100 percent of the costs of many highway projects).

That deal became less sweet by the 1980s, when the Reagan administration got the federal match down to 50 percent, as Los Angeles experienced when that region got its Metro Rail going (as I chronicled in the book Railtown). But still, 50 percent is pretty good, even if it’s stiffing urban taxpayers who disproportionately contribute transportation taxes to the U.S. government but see less return.

With high speed rail, it could have been a similar story: a statewide consensus on route and funding stream came together in 2008 with a successful $10 billion bond issue passed by the voters. Since then, the governor and legislature have committed a substantial amount of cap-and-trade funds, which could add another $5 and possibly $10 billion or more by 2020.

But with these possible $20 billion in state funds, the federal government has only committed $3.5 billion in matching dollars to date. That’s hardly the 50% match that the federal government typically spends.

But with these possible $20 billion in state funds, the federal government has only committed $3.5 billion in matching dollars to date. That’s hardly the 50% match that the federal government typically spends.

At that percentage, the federal government would have to kick in $20 billion total (a fraction of the $2 trillion spent on recent wars in the Middle East, for example). Then the system would have enough dollars to get solidly to San Francisco or perhaps to Los Angeles.

But the U.S. Congress is polarized against high speed rail and unwilling to spend much money on non-automobile modes of transportation, due to Republican resistance. And that dynamic has been in place since the Tea Party election of 2010.

All of this may explain why the high speed rail business plan has been criticized by state oversight agencies for not “showing us the money” on these initial construction phases. The reality is that high speed rail doesn’t have the money. And it won’t until Congress changes.

But given that high speed rail is a long-term, multi-decade process, the system’s backers may have a shot at waiting things out until another wave election or change in the political environment occurs. In short: the plan is to pray for a better congress.

But you can’t exactly write that in a business plan.

You can take a new sleeper bus from San Francisco’s Caltrain station to Santa Monica, for $65 each way. Not bad.

Meanwhile, perhaps with some improvements to the Tehachapi crossing to get Amtrak over the mountain, we could have a good rail connection between the cities as well.

In the long-term, I believe we’ll need high speed rail. But we should be thinking about interim measures like these in the meantime, given how uncertain the high speed project is.

I guess it was inevitable. By switching the initial route from Southern California to Northern California in the hopes of salvaging the system, High Speed Rail Authority leaders have unleashed political angst in Southern California, per Greenwire (paywall):

That initial segment would use up all existing funds, and there’s no clear source for the remaining money. Southern California supporters worry that their region will be left out of the system if it can’t be extended.

“You can’t say you can do something without saying how you are going to pay for it,” said Hasan Ikhrata, executive director of the Southern California Association of Governments. “This is a must. If you don’t have the money in the bank, I understand that. But you can’t assume the money is going to fall from the sky. You have to have a path. You can’t be silent totally.”

Ikhrata added, “If they build a system that fails to connect Los Angeles, this will be the biggest failure of an infrastructure project we have ever had in the state of California. It will be sad for future generations.”

That last quote is unfortunately more likely than many people admit. The system badly needs to find cash somewhere, but no investors will step up with so much uncertainty and such an economically inefficient route.

The most recent play may be to dangle the possibility of connecting this initial segment to Bakersfield and up to San Francisco, in the hopes of enticing House Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy to pony up a couple billion extra federal dollars. But McCarthy seems unlikely to go for it, given the intense opposition to the project among his base.

So state leaders will carry on, burning through the state bond money, federal grant, and cap-and-trade funds — and assuming that ongoing litigation doesn’t go against them. Perhaps if they can at least stay the course for another few years, the politics will change at the federal level to unlock more cash. Or extending state cap-and-trade beyond 2020 may provide assurance for private investors.

Because otherwise, this project may truly become the biggest infrastructure failure California has ever seen.