High speed rail has been in the news lately for all the wrong reasons, with a scathing state audit indicating that hundreds of millions of dollars — if not billions — may ultimately be wasted by starting construction too early to meet political deadlines, as well as other mismanagement.

I debated the future of the system last week on KPCC radio in Los Angeles, on the program Airtalk with Larry Mantle. Sparring with me was James Moore, civil engineering professor at the University of Southern California (and longtime anti-rail academic).

You can listen to the first part of the show on the Airtalk website, but the full audio (including my last rebuttal to Prof. Moore) is available here.

The short story? Some of the mismanagement is due to the complicated politics of building such a controversial system through the heart of Tea Party California opposition, while the system in general will still be needed to serve a growing population and connect the Central Valley cities to the prosperous coastal economies.

Some big wins for California (and therefore national) climate policy last night:

Some big wins for California (and therefore national) climate policy last night:

- Lt. Governor Gavin Newsom is elected governor, which means the state will continue its climate leadership on various policy fronts

- Prop. 6 loses, which would have repealed the gas tax increase and meant less funding for transit going forward

- Prop. 1 wins, which could provide more money for affordable housing in infill areas, reducing driving miles as a result

- The Democrats win the U.S. House of Representatives, which has a host of implications:

- Oversight of the U.S. Departments of Energy, Interior, and Transportation, plus E.P.A., which have all issued various regulations that hurt climate goals in the state

- Potentially more funding in future budget bills for crucial transit infrastructure, including high speed rail

- Potentially more funding and fiscal support for clean tech, like renewables, energy storage and electric vehicles, depending on how budget negotiations proceed

- Oregon Governor Kate Brown wins re-election, which means that state is well-positioned to adopt cap-and-trade next year, making it the first U.S. state to link to California’s program and potentially creating a multi-state building block for an eventual national carbon trading program

And on the housing front, Governor-elect Newsom has set ambitious goals for building more homes in the state, which if done in infill areas could bring crucial climate and air pollution benefits from reduced driving per capita. Pro-housing “YIMBY” candidates also bolstered their ranks in state government, with the election of former Obama campaign staffer Buffy Wicks to the Berkeley Assembly district.

Setbacks nationally (beyond continued Republican gains in the U.S. Senate) included the defeat of some state ballot initiatives, including a carbon tax in Washington, an anti-fracking measure in Colorado, and a renewable portfolio initiative in Arizona — though Nevada voters did embrace a 50% renewable target by 2030 at their polls.

All in all, a positive night for climate policy in California and beyond.

San Francisco is about to open its new $2.2 billion Transbay Terminal in downtown, current home to transbay bus service and future home to Caltrain and high speed rail. I had an opportunity to tour the facility last week ahead of its big public opening on August 12th (photos below).

The new terminal replaces a 1930s era bus depot that used to receive San Francisco’s since-shuttered intercity electric trains coming off the lower deck of the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge. But the eight-year construction project has been mired in controversy over the typical delays and budget-busting that you see with big new infrastructure projects. And it also has been blamed for contributing to the nearby Millennium tower sinking and shifting, based on the dewatering practices used to excavate the site.

My takeaway from the tour? It’s a beautiful building that will really help smooth bus transportation access to this growing neighborhood south of Market Street. And the other immediate benefit will be the rooftop park, which is reminiscent of Manhattan’s highly successful “high line” walkway.

But the long-term payoff will be if and when Caltrain and High Speed Rail begin service to its now empty basement level — though that may take more than a decade to come to fruition.

Below are some photos I took from above, within, and below the site.

First up, the view of the 5.4 acre rooftop garden from the Transbay Terminal project office:

Here’s a small-scale model displayed in the project office:

Here’s a small-scale model displayed in the project office:

Once inside the “Grand Hallway” of the terminal on the ground floor, the design team planned a mosaic floor covered in bright California poppies:

Once inside the “Grand Hallway” of the terminal on the ground floor, the design team planned a mosaic floor covered in bright California poppies:

In the basement, possibly the most hopeful yet depressing sight: where Caltrain and possibly high speed rail trains will arrive and depart (probably in the 2030s), serving downtown San Francisco with thousands of passengers each day (pending the funding to complete these multi-billion dollar projects):

On the second floor, you’ll find the new bus bridge from the terminal on that level, taking buses directly onto the Bay Bridge for service to the East Bay and beyond:

On the second floor, you’ll find the new bus bridge from the terminal on that level, taking buses directly onto the Bay Bridge for service to the East Bay and beyond:

And on the top floor, the aforementioned 5.4 acre rooftop park. Although it’s not as convenient to access as a street-level park, the concert series in this future bandstand and other activities should attract people, plus the nice views:

The half-mile bike- and scooter-free walkway around the top feels like a West Coast high line:

The park also features a fun access feature: a new gondola that will ferry people to the top from the street, hopefully in an efficient manner. The gondola won’t open until late August or early September:

Families with children will be welcome at this playground on the rooftop:

Overall, the terminal will be a real jewel for this part of San Francisco and a nice way to take transit. But it’s full potential won’t be realized until federal, state and local officials find the money first to extend Caltrain into it and then one day to bring in high speed rail to downtown San Francisco.

How fast will California’s high speed rail system actually go, once it’s fully built between San Francisco and Downtown Los Angeles? Robert Poole at the libertarian Reason Foundation (and an outspoken opponent of the project) runs the numbers:

How fast will California’s high speed rail system actually go, once it’s fully built between San Francisco and Downtown Los Angeles? Robert Poole at the libertarian Reason Foundation (and an outspoken opponent of the project) runs the numbers:

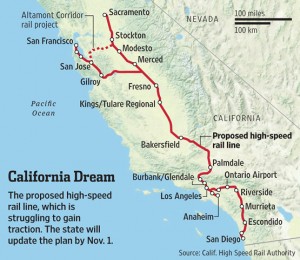

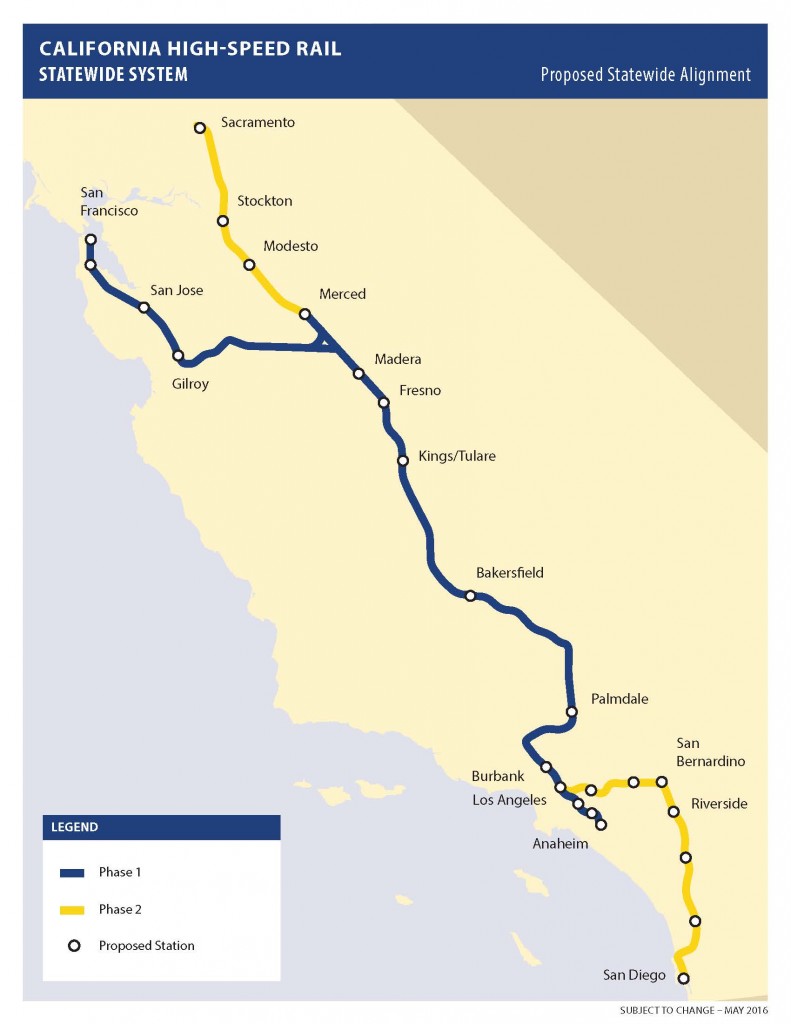

Each time the business plan gets revised, more of the total 434 miles will operate at speeds well below the 220 mph touted by proponents. Los Angeles Times reporter Ralph Vartabedian in March identified another 30 miles that will run at lower speed: the route between San Jose and San Francisco. Instead of running on an elevated track, the HSR will operate on ground-level tracks through a highly urbanized area with numerous grade crossings. CHSRA claims it can safely operate this stretch at 110 mph—but that is not the case for the privately-funded Brightline train in South Florida. Between Miami and West Palm Beach, its allowed top speed is 70 mph—and that is with extensive safety improvements to grade crossings. Reviewing various CHSRA documents assessed by Vartabedian, I found 91 miles that will likely be restricted to 70 mph and another 45 miles in tunnels where speeds will likely be no higher than 150 mph. Assuming that on the remaining 298 miles the average speed will be 200 mph (due to grades, slowing down for the slower sections, etc.), my estimate of the total elapsed time between Los Angeles and San Francisco is 3.09 hours. And that is a problem, since the ballot measure approved by the voters requires that nonstop journey to take no longer than 2.67 hours.

If Poole is right (and I haven’t reviewed his methodology or assumptions to know), will a 3+ hour ride between San Francisco and LA be a problem for attracting riders? It certainly doesn’t sound as compelling as 2 hours and 40 minutes required by the 2008 ballot initiative. And if you include door-to-door travel time, many riders could be looking at 5 hours between the two cities. That amount of time starts to look equivalent to flying, once you factor in travel to and from the airport, security, and waiting to board and de-plane.

So the only advantage over flying that high speed rail would have at that point would be a slightly cheaper fare, potentially nicer ride (smooth travel over land with great views), and the ability to access interim stops like Fresno or Bakersfield.

Of course, high speed rail has bigger concerns at this point than worrying about long-term travel times. The system’s leaders are struggling just to build the first truly usable section between Fresno and San Jose, and they have no money to get anywhere close to Los Angeles at this point.

But anything that we can do now to speed up the overall travel time will certainly yield ridership benefits down the, er, road.

The California High Speed Rail Authority released its 2018 draft business plan on Friday, and the news is not good. Not only have costs gone up with no new revenue in site, the authority now admits it’s unlikely to build any actual high speed rail service for at least a decade.

The California High Speed Rail Authority released its 2018 draft business plan on Friday, and the news is not good. Not only have costs gone up with no new revenue in site, the authority now admits it’s unlikely to build any actual high speed rail service for at least a decade.

How did we get to this unfortunate place? Since voters originally approved a $10 billion bond issue to launch the system in 2008, two important events happened:

1) Central Valley representatives insisted the system start in the Valley, with no benefit to the coastal cities. While the system was originally billed as a quick way to serve Los Angeles and San Francisco, San Joaquin Valley representatives saw it as an opportunity to diversify and grow the Central Valley economies, by linking this largely impoverished part of the state to the thriving coastal cities. As a result, they insisted on starting the system in the Valley, where it would provide no benefit to the major population centers on the coasts. It’s the equivalent of starting LA Metro Rail in the suburban San Fernando Valley, or BART in the East Bay suburbs. Most train systems need to go back to voters for multiple rounds of funding. But in this case, voters in Los Angeles and San Francisco have no stake in the system. Had the system instead been started between San Francisco and San Jose and also between Los Angeles Union Station and Anaheim (and up to northern Los Angeles County), there would have been something to show for the initial investment and more political support to complete it (and less litigation and opposition from the Central Valley residents).

2) Republicans took over Congress in 2010 and have since refused to return Californians’ tax dollars to the project. With that Tea Party election that year, Republicans withdrew the federal purse strings for the project. While the federal government is happy to pay 90 to 100 percent of the costs of new highways, and 50 percent of the costs for new rail transit, so far California residents have been on the hook for $17 billion of the roughly $20 billion in costs to date.

Nothing can be done about the first event, which is a mistake that the authority has since tried to rectify by dedicating some funds to improve Caltrain and Metrolink in the coastal cities.

The second event could potentially be remedied this November, if a “blue wave” removes Republican control of Congress. While President Trump could veto any subsequent infrastructure plans that funds high speed rail, he will have lost leverage at that point. And revenue to fund non-automobile infrastructure like high speed rail could come from sources like a new carbon tax, passed via reconciliation in the Senate.

Still, hoping for a political shift is not exactly a great business plan. In the meantime, the authority appears set to finish the 119 mile first segment in the Valley. Then, absent new revenue, they’ll probably hand it over to Amtrak to run regular diesel trains on it, biding time until political and economic fortunes change in the state and the country at large.

Google made headlines recently for buying a huge property adjacent to the future downtown San Jose high speed rail station, per the San Francisco Chronicle:

Google made headlines recently for buying a huge property adjacent to the future downtown San Jose high speed rail station, per the San Francisco Chronicle:

Google has been in negotiations with San Jose since June for a planned “village” that would feature up to 6 million square feet of office, research and development, retail and amenity space near San Jose’s Diridon Station. The development could bring 15,000 to 20,000 jobs, Nanci Klein, San Jose’s assistant director of economic development, previously told The Chronicle.

To be sure, this property would be valuable for Google even without high speed rail, as it’s at the heart of San Jose’s light rail network. But high speed rail will only increase the value, as it would give Google employees high-speed train access to businesses to the south and through the San Joaquin Valley — and eventually Los Angeles.

So the question is: would a property owner like Google be willing to help finance high speed rail, which is badly in need of cash? It’s the old school way of funding trains: leverage the future increases in property values around the stations to finance the transportation.

Given the slow trickle of state dollars and nonexistent federal funds, high speed rail leaders will need to get creative about how to find money to keep construction going. A large company like Google could greatly help with the search.

UPDATE: Initial reports that the electric vehicle tax credit was killed in the Senate version may have been inaccurate. The text of the amendment contained some obscure language that actually indicates that it was not adopted in the ultimate bill.

Donald Trump’s electoral college win a year ago certainly promised a lot of setbacks to the environmental movement. His administration’s attempts to roll back environmental protections, under-staffing of key agencies enforcing our environmental laws, as well as efforts to prop up dirty energy industries have all taken their toll this year.

However, until the tax bill passed the Senate this week, much of that damage was either relatively limited in scope or thwarted by the courts. But the new tax legislation now passed by both houses of Congress, and still in need of reconciliation and a further vote, could dramatically undercut a number of key environmental measures in ways we haven’t yet seen from this administration.

Originally, there was some hope that Republicans in the U.S. Senate would weaken some of the draconian environmental measures in the original House tax bill. But that was largely dashed by the late Friday night, partisan vote in the U.S. Senate. First, the bill targets clean technology while promoting dirty energy:

- The renewable energy tax credits for wind and solar are severely undercut by an obscure provision in the bill called Base Erosion and Anti-abuse Tax (BEAT), as Greentech Media reports. While analysts are still reviewing the provisions to discern the likely impact, initial assessments are that this bill language could greatly hurt the industry by decreasing the value of the credits.

- Similarly, the reinstatement of the alternative minimum tax for corporations, which was not in the House bill, also hurts the market for renewable tax credits, if not devastates it. By inserting this provision at the very last minute, Senate leaders attempted to offset some of the other tax cuts and projected deficits by ensuring corporations pay a minimum tax. The problem is that it renders many tax credits worthless, as businesses will no longer need them. Particularly hurt are wind energy projects, which rely on the production tax credit, as well as solar projects that rely on the investment tax credit.

- As a dirty cherry on top, the Senate bill opens the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to oil drilling.

On housing, the tax bill has the potential to devastate affordable housing. Affordable projects often rely on tax credits for financing. As Novogradac & Company writes, the BEAT provision will dampen corporate investors from claiming tax credits like the low-income housing tax credit (LIHTC), new markets tax credit (NMTC), and historic tax credit (HTC), all used to fund affordable and other infill projects. Other changes in the bill promise further dampening of financing for affordable housing.

The only good news for environmental and housing advocates is that there is still a chance to make changes in the bill through the conference committee. And that the provisions here can be rescinded in 2021 with a new congress and president.

California’s Central Valley is the state’s defining geographical feature. It’s the country’s breadbasket, with over 400 commodity crops, including all the almonds grown in the country. At the same time, it’s poverty-stricken, with Fresno the second poorest city in the U.S., and yet oil rich down by the deeply Republican Bakersfield.

California’s Central Valley is the state’s defining geographical feature. It’s the country’s breadbasket, with over 400 commodity crops, including all the almonds grown in the country. At the same time, it’s poverty-stricken, with Fresno the second poorest city in the U.S., and yet oil rich down by the deeply Republican Bakersfield.

It’s also one of the most environmentally vulnerable region in the state, with one of the most polluted air basins in the country. And as the Los Angeles and San Francisco Bay Area regions say no to new housing, sprawl is spreading into the Valley from these areas, as workers choose cheap housing and super commutes. Sprawl is also the norm around the Valley’s large cities along Route 99 on the eastern side. Like Los Angeles before it, the flat terrain means the region has no real geographical impediments to sprawl.

High speed rail could make the sprawl even worse, as the train will spur growth in places like Fresno, which will be just an hour or so from the booming coastal job centers (Berkeley and UCLA Law released a report on the subject in 2013, along with recommendations to combat the problem).

High speed rail could make the sprawl even worse, as the train will spur growth in places like Fresno, which will be just an hour or so from the booming coastal job centers (Berkeley and UCLA Law released a report on the subject in 2013, along with recommendations to combat the problem).

People in the Valley are well aware of the risk. Former Fresno mayor Ashley Swearengin, a rare Republican high speed rail supporter, tried to do the right thing to encourage more downtown-focused growth in Fresno and not allow the urban core to get hollowed out by competition from nearby cheap sprawl.

But Mayor Swearengin and other downtown booster’s efforts are threatened by Fresno’s neighbor Madera County next door, whose leaders prefer the model of continued sprawl over productive farmland and open space. The result will be the usual negatives we see elsewhere in the state: more traffic, worse air quality, and lost natural resources.

Marc Benjamin and BoNhia Lee detailed the new sprawl projects in the Fresno Bee last year:

Madera County is on the verge of a building boom that creates the potential for a Clovis-sized city north and west of the San Joaquin River, with construction starting this spring.

Riverstone is the largest of the approved subdivisions in the Rio Mesa Area Plan. It’s underway on 2,100 acres previously owned by Castle & Cooke on the west side of Highway 41 and north and south of Avenue 12. Castle & Cooke had plans to build there for about 25 years.

It’s the first of several subdivisions in the county’s area plan to be built. Over the past 20 years, Riverstone and other projects were targeted in lawsuits, many of which have been settled, but some still linger. But some critics contend that the new developments will worsen the region’s urban sprawl.

Principal owner Tim Jones’ vision for his nearly 6,600-home development a few miles north of Woodward Park is a subdivision with six separate themed districts. Riverstone will compete for home buyers with southeast Fresno, northwest Fresno, southeast Clovis and a new community planned south and east of Clovis North High School.

The Rio Mesa Area Plan will result in more than 30,000 homes when built out over 30 years. About 18,000 homes have county approval. The contiguous communities could incorporate to create a new Madera County city that could dwarf the city of Madera and have a population greater than Madera County’s current population of 150,000.

In the coming years, an additional 16,000 homes are proposed in Madera County. On the east side of the San Joaquin River, in Fresno County, about 6,800 homes are approved in the area around Friant and Millerton Lake.

Defenders of these sprawl projects claim that some are mixed-use developments located close to distributed job centers, minimizing the chances that they will become merely bedroom communities of Fresno. But as the development continues outward, it undercuts the market for infill housing, leading to a vicious downward spiral that we saw hit downtowns throughout the country in the middle of last century.

The best way to solve these growth issues is better regional cooperation, particularly around some type of urban growth boundaries. The growth boundaries can be de facto through mandatory farmbelts, rings of solar facilities, and possibly better pricing on sprawl projects to account for their externalities. Or they can be actual limits on growth and urban expansion outside of already-built areas.

Without concerted action, and with the high speed rail coming from Fresno to San Francisco soon, we may soon find that it’s too late to undo the damage in the Central Valley.

After I just wrote that the cap-and-trade extension to 2030 throws a lifeline to high speed rail in California, I read in today’s San Francisco Chronicle that California Republicans think they’ve potentially “de-railed” their hated train by helping to extend the program:

In extending California’s cap-and-trade system of controlling greenhouse-gas emissions through 2030, lawmakers approved a Republican plan this week to put a constitutional amendment before voters that seeks to give the minority party more say over how the program’s money is spent. One-fourth of that money — more than $1 billion so far and $500 million projected a year in the future — goes toward high-speed rail, a project that Republicans widely oppose.

With the proposed $64 billion train line between Los Angeles and San Francisco facing not only Republican opposition but financial struggles, any cut in funding from the cap-and-trade program could be fatal.

“This absolutely calls into question the viability of high-speed rail going forward,” said Assemblyman Marc Steinorth, R-Rancho Cucamonga (San Bernardino County), who voted to extend cap and trade in part because of the proposed constitutional amendment. “If the bullet train can’t prove its worth, (this amendment) provides a pathway to ending the funding for the boondoggle once and for all.”

The logic to me is basically ridiculous. First, the constitutional amendment has to be passed by the voters, which is a big “if.” Second, the amendment won’t even affect any dollars until 2024, at which point the vote in the legislature would have to take place. And finally, even if a spending plan kills high speed rail, a simple majority vote of legislators after 2024 can change the spending priorities again.

The bottom line: the extension of cap-and-trade both shored up the existing cap-and-trade market through 2020 by increasing business confidence that the program is here to stay, and it gave the train line at least 4 additional years after 2020 to compete for funding under the program.

To be sure, there are still funding risks for high speed rail by relying on cap and trade. The legislature can try right away to tweak the funding formulas for how auction proceeds are spent, although this governor would likely veto any plan that diminishes funds for his priority project. And the amount of money from cap and trade may not be enough to finish the first section anyway from north of Bakersfield to San Jose.

Ultimately, the best bet for high speed rail is a new U.S. Congress that pays its share of federal dollars for the project, or a private investor to step up, which so far hasn’t happened. But the extension of cap and trade can only be seen as a positive at this point for high speed rail.

Last night the California Legislature scored a super-majority victory to extend the state’s signature cap-and-trade program through 2030. It was a rare bipartisan vote, although it leaned mostly on Democrats. My UCLA Law colleague Cara Horowitz has a nice rundown of the vote and its implications, as does my Berkeley Law colleague Eric Biber on the bill.

Lost in the politics is what this means for high speed rail. The system has a fixed and dwindling amount of federal and state funds at this point, and it’s relying on continued funding from the auction of allowances under cap-and-trade to build the first segment from Fresno to San Jose and San Francisco.

Lost in the politics is what this means for high speed rail. The system has a fixed and dwindling amount of federal and state funds at this point, and it’s relying on continued funding from the auction of allowances under cap-and-trade to build the first segment from Fresno to San Jose and San Francisco.

If the auction was declared invalid or ended at 2020 with depressed sales, the system would be in major jeopardy of collapsing before construction even finished on the first viable segment. Now it has some assurance of access to funds.

But of course it’s not that simple. The bill that passed yesterday has diminished available funds set aside for the programs that have been funded to date with cap-and-trade dollars. As part of the political compromises, more auction money will now go to certain carve-outs, like to backfill a now-canceled program for wildfire fees on rural development.

And another compromise may put a ballot measure before the voters, passage of which would require a two-thirds vote for any legislative spending plan for these funds going forward. That means Republicans — who generally hate high speed rail — would be empowered to veto future spending proposals.

Still, high speed rail once again has a lifeline, as do the other programs funded by cap-and-trade, such as transit improvements, weatherization, and affordable housing near transit. It’s an additional victory beyond the emissions reductions that will take place under this extended program.