Lithium ion batteries like those found in electric vehicles have become dramatically cheaper over the past 10 years. But rising demand for cobalt, as well as supply shocks from the Democratic Republic of Congo’s dominant position, threaten this progress. Cobalt prices have doubled since 2016 as a result.

Cobalt samples in Chile

However, we’re now seeing industry respond in two ways. First, mining interests are expanding beyond Congo to address the supply shortage and also diversify the countries holding jurisdiction over the largest deposits. Bloomberg reports that Chile has emerged as a potential site of some rich cobalt deposits, based on some historical research that country’s officials recently did:

Renewed interest in La Cobaltera [Chile] began to emerge last year after Chilean authorities discovered records long buried in the archives of the national geological agency. They showed more than 7 million tons of cobalt ore was mined in the country between 1844 and 1941. The mineral was extracted mainly by German immigrants, who sent it to Europe presumably to manufacture military equipment.

If this discovery holds up, it could provide an important supply source to break Congo’s monopoly, with its human rights and governance concerns.

Second, and more exciting, battery engineers are developing products that require much less cobalt. Utility Dive discussed this trend at Tesla:

In the company’s first quarter 2018 earnings update, Tesla CEO Elon Musk said the company had moved to higher density batteries while reducing the cobalt content of its battery packs. And in June, Musk told shareholders his company would continue to push battery costs down, breaking through the $100/kWh barrier for li-ion cells later this year.

Not only would less cobalt in batteries be a good thing for economic and environmental reasons, it also means prices can continue to decrease. And lower prices mean lower-income car buyers will be able to afford more and better electric vehicles, thereby reducing greenhouse gas emissions from transportation.

These two innovations on cobalt therefore represent promising trends that hopefully will continue for battery production, securing the supply chain for this critical clean technology.

The U.S. federal government has not provided much hope to climate advocates. The Trump administration has launched a full-scale assault on climate policies. But even under Obama, the level of action to tackle greenhouse gas emissions was not on pace with what’s needed to avert catastrophic warming.

But fortunately cities and states can do a lot on their own. America’s Pledge, an initiative co-founded by California Gov. Jerry Brown and former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg, recently released a report that provides “bottom-up” strategies for cities, states, and businesses to address climate change. As Utility Dive summarized, the ten opportunity areas include the following:

- Expanding renewable energy

- Accelerating retirement of coal power

- Retrofitting buildings for energy efficiency

- Electrifying buildings’ energy use

- Accelerating the adoption of electric vehicles

- Phasing out the use of hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs)

- Preventing methane leaks from gas wells

- Reducing methane leaks in cities

- Increasing carbon sequestration on land

- Establishing state and regional carbon markets

All of these areas do not necessarily require federal policy support (although it would be helpful), and many involve limiting emissions from powerful “short-lived climate pollutants” like methane and HFCs (I would also highlight land use and transit policies to promote smart growth as an important area of focus).

Straightforward examples at this level of policy making include developing energy efficiency building codes, steering municipal utilities to procure more renewable energy and energy storage, and providing incentives for electric vehicle adoption, such as through more charging stations and municipal fleet purchases.

But developing these policies at the state and local levels is more than just an effort to salvage climate policy in the face of federal inaction. We should be pursuing these policies anyway, for multiple reasons. Specifically, state and local action:

- Creates a decentralized web of climate policies that can’t be reversed with one bad national election that might deliver Congress or the presidency to climate deniers — producing more policy stability overall.

- Fosters local innovation that might result in successful programs or technologies that can scale nationwide or globally.

- Provides more accountability and flexibility on policy implementation, since decision makers will be in close proximity to those affected by the policies, both good and bad.

So while federal inaction on climate change can be a source of frustration and potential peril, it may also provide us with a good excuse to take action that needed to happen anyway — a silver lining on an otherwise dark storm cloud.

It’s fine if you don’t like Elon Musk. But it’s a mistake to let antipathy for Musk’s ideas, businesses and public persona color your view of electric vehicles, and more specifically Tesla.

And that’s exactly what happens to token “conservative” New York Times opinion writer Bret Stephens. Stephens is otherwise known (at least to me) as a climate skeptic. But in a scathing and highly personal attack on Elon Musk, he betrays ignorance of another subject: electric vehicles.

After comparing Musk to Trump, he makes some misleading charges about Tesla:

Strong words — too strong, if you ask the satisfied customers of Tesla’s Model S (base price, $74,500) and X ($79,500). But Tesla is supposed to be the auto manufacturer of the future, not a bauble maker for the rich.

The company has rarely turned a profit in its nearly 15-year existence. Senior executives are fleeing like it’s an exploding Pinto, and the company is in an ugly fight with the National Transportation Safety Board. It burns through cash at a rate of $7,430 a minute, according to Bloomberg. It has failed to meet production targets for its $35,000 Model 3, for which more than 400,000 people have already put down $1,000 deposits, and on which the company’s fortunes largely rest.

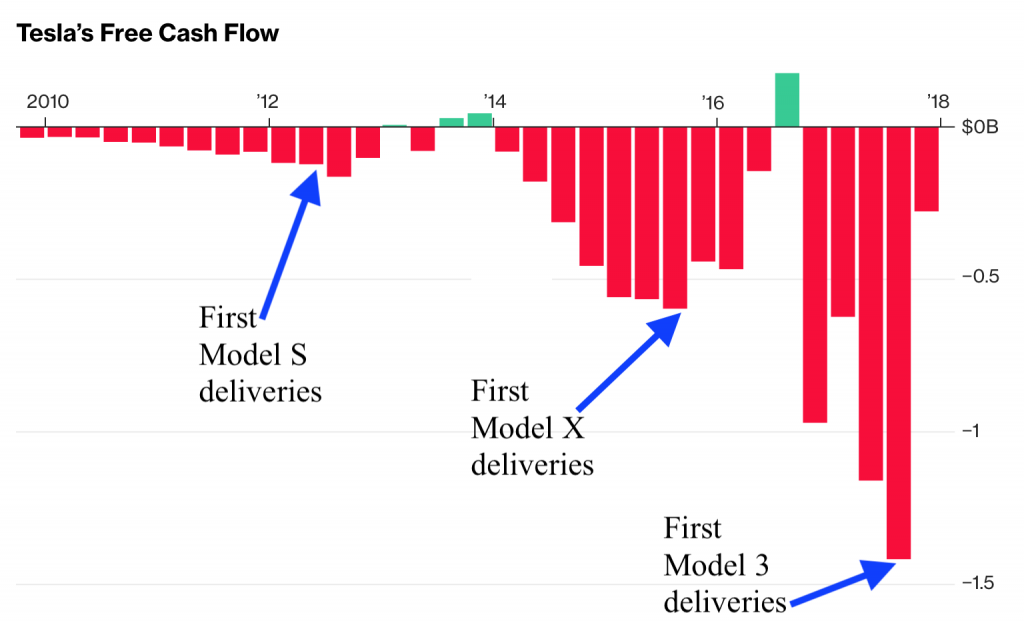

Stephens makes Tesla sound like a money-losing luxury automaker. But Tesla could have easily turned a profit a long time ago, if it was in the short-term profit game. But it’s burning cash precisely because it’s scaling up a massive battery, solar panel and mass-market vehicle business. Check out this chart on Tesla cash flow from Ars Technica:

It’s silly for Stephens to take a snapshot of Tesla’s current losses without broader context and insight into the company’s business plan. He whiffs on this score.

It’s silly for Stephens to take a snapshot of Tesla’s current losses without broader context and insight into the company’s business plan. He whiffs on this score.

But it gets worse. He then lobs a broad attack against EVs in general:

Tesla, by contrast, today is a terrible idea with a brilliant leader. The terrible idea is that electric cars are the wave of the future, at least for the mass market. Gasoline has advantages in energy density, cost, infrastructure and transportability that electricity doesn’t and won’t for decades. The brilliance is Musk’s Trump-like ability to get people to believe in him and his preposterous promises. Tesla without Musk would be Oz without the Wizard.

Much of the blame for the Tesla fiasco goes to government, which, in the name of green virtue, decided to subsidize the hobbies of millionaires to the tune of a $7,500 federal tax credit per car sold, along with additional state-based rebates. Would Tesla be a viable company without the subsidies? Doubtful. When Hong Kong got rid of subsidies last year, Tesla sales fell from 2,939 — to zero. It may be unfair to describe Tesla as Solyndra on wheels, but only slightly.

It’s time for fact checks. First, lithium ion batteries and electricity rival gasoline in all categories Stephens mentions. Electricity is ubiquitous (and locally produced). Batteries can recharge in minutes with technology now being introduced on the market, just like a gas station. And cheaper battery packs deliver the range today of a full tank of gas. And on all these fronts, the technology and infrastructure is set to improve in the next few years — not decades, as Stephens suggests.

But even more important, electricity as a fuel doesn’t poison our air and lungs like burning gasoline — or leave us dependent on foreign governments for a global commodity. Gasoline is not priced for those externalities. Since Stephens doesn’t accept climate science, he may not care. But the rest of us should.

And this notion that Tesla survives on government handouts is also misleading. Many Tesla customers are wealthy enough where the tax incentives and rebates don’t factor into their decision-making, according to data collected in California on rebate customers. If anything, Tesla is now hurt by government incentives for fossil fuels and rival automakers with new electric vehicles on the market.

In short, Stephens is ignorant on this topic and unfortunately has written a column that spreads misinformation on a critical climate-fighting technology.

Energy economists don’t like rooftop solar. Depending on the policy involved, it can entail significant and cost-inefficient ratepayer subsidies. For example, Lucas Davis at UC Berkeley’s Energy Institute at Haas recently calculated that non-rooftop solar customers are paying $65 per year to subsidize solar customers. He got this number by taking the difference in price between a retail credit for every kilowatt hour delivered from a rooftop solar customer to the grid and the wholesale price that this electricity actually costs.

In California, the average retail electricity price is about $0.18/kWh, while wholesale rates are close to $.04/kWh. That means that utilities are losing about $.14/kWh for each retail credit they give rooftop solar customers for their surplus solar (since they could have purchased the electricity for much cheaper elsewhere). And since utilities have a lot of fixed costs sunk in grid infrastructure, Davis was able to calculate the total subsidized amount spread over non-rooftop solar customers and divide it by ratepayers to arrive at the $65 per year in ratepayer cost-shifting.

Ultimately, it’s that cost-shifting that explains why energy economists like Davis and Serverin Borenstein hate California’s new solar rooftop mandate so much.

But this cost-shifting doesn’t have to happen — it’s due specifically to electricity rate policies. And in that respect, Hawaii tells a different and more promising story. Ultimately, I believe that state’s rooftop solar policies are where California is headed soon.

In Hawaii, utilities stopped offering full retail credit for surplus rooftop solar back in 2015. Instead, they essentially pay solar customers the wholesale rate for their surplus. As a result, utilities aren’t losing what would be $.14/kWh in California for each retail credit they give. So no cost-shifting happens.

And the impact on the ground for Hawaii rooftop solar customers? Homeowners are still ordering solar panels, but now home battery installations are starting to take off, too, as this state government chart from Utility Dive shows:

To be sure, it’s still relatively early days of the policy and the on-the-ground response. But given plunging battery prices, as well as cheaper solar installations, this solar-plus-battery technology solution seems like a great way to address complaints about cost-shifting and ratepayer subsidies. It also points to a path forward for the rest of the country, with a future of rooftop solar on most homes — and batteries in every basement or garage.

The upside is more clean technology deployed, a bigger market to bring down costs further on solar and home energy storage, reduced greenhouse gas emissions, and improved grid resilience in the case of extreme weather or other disasters. Not a bad deal all around, and one California will probably eventually see as well, as its rooftop solar policies evolve.

The vote last Wednesday at the California Energy Commission to mandate solar on all new residential rooftops may have been unanimous, but energy experts are still definitely divided. Most prominently, UC Berkeley energy economists have been out in force to argue against it as economically inefficient.

First, Severin Borenstein drafted a hasty letter in opposition to the commission, and then his colleague James Bushnell drafted a Sacramento Bee op-ed against it. Bushnell also wrote a longer post explaining his rationale:

As more aggressive and difficult carbon reduction goals loom for California, there seems to be an inclination to grasp at every policy we can think of that can add to the carbon reduction body count. It’s a spaghetti on the wall approach to carbon policy. However, it’s now more important than ever to focus on the efficient tools and policies that can push our carbon reductions in cost-effective ways. We could get away with inefficient policies like net-energy metering and zero-carbon schools when they were relatively small polices. From here on out the costs are going to start to matter.

The points they make similar: rooftop solar is not cost-effective, compared to utility-scale solar, and the policy may actually cost more money than we think because it will leave existing investments in power plants and solar PV facilities essentially stranded as useless during sunny days. It will also force ratepayers without solar to continue subsidizing homeowners with panels.

To sum it all up, Vox’s David Roberts lists all the pros and cons to the policy. For my part, I find two of the “pro” arguments convincing. Especially this one:

Time-of-use rates mean new rooftop solar could drive new storage and demand shifting.

California’s three big utilities are shifting to time-of-use rates for residential customers — meaning ratepayers will be charged more for electricity when it is more valuable. This will also affect net metering; if retail rates are lower during the midday solar surge, net metering compensation will be lower too.

That will give homeowners incentive to shift some of their solar energy around, which they can do with home energy storage — and helpfully, under the new building code, storage counts as compliance with efficiency mandates. That should get a lot of storage, and with it a lot of responsive demand, into California homes, which should help stabilize the grid.

In the long run, California will not be able to maintain net metering as a policy to compensate solar rooftop owners for their surplus production. Like Hawaii, my guess is that the state will move to paying homeowners for excess solar at the wholesale rate, as a cash payment. Combined with time-of-use or real-time electricity pricing, homeowners will then have an incentive to buy home batteries to capture their surplus solar, rather than rely on credits from their utility. The resulting energy storage deployment (and change in electricity demand) will improve the economics of rooftop solar and also the grid profile of these homes, perhaps lessening the negative effect on existing utility-scale power plants.

Second, I find convincing the argument that the rooftop solar boom will drive down prices for solar, which will benefit everyone (including utility-scale installers), as well as help promote demand for clean technology more generally, from batteries to electric vehicles (a variation on the “rooftop solar is contagious” argument).

But perhaps more importantly, we should keep in mind two things about this decision:

- it cannot be viewed in isolation, as the state is trying out all sorts of policies to address climate change (and our housing crunch); and

- because it is a regulation, if facts on the ground change, the commission is well suited to reverse course or alter the mandate in some fashion in a timely manner. That’s the beauty of regulation over legislation.

Given the many potential upsides, it’s worth it for the state to pursue this experimental policy and ideally separately encourage electricity rates that optimize the rooftop solar deployment. And in the meantime, state leaders can monitor implementation and adjust it as technologies and other energy policies change.

As I blogged about yesterday, the California Energy Commission unanimously approved a new solar mandate for all new residential construction in the year 2020. I spoke to KPCC radio in Los Angeles and Reuters about the decision.

While I think the mandate is sound economically and environmentally, Severin Borenstein at UC Berkeley takes a contrary view on the economics. Severin doesn’t like rooftop solar in general, as opposed to more cost-efficient utility-scale solar, and he foresees problems with ratepayers subsidizing the installations.

For my part, I think it’s clear the state is heading away from the retail credit model of subsidizing excess solar production, which Severin doesn’t like. Instead, state regulators will likely to move to paying the wholesale rate for surplus solar from rooftops, as Hawaii basically now does. So new batteries will likely accompany these home solar installations, because they will be an economically sound technology to capture surplus solar rather than feed it to the grid for a relatively puny wholesale rate. That’s what we see consumers doing in Hawaii in response to the loss of retail credit.

And in that respect, the new commission rules could help, as they also give batteries “compliance credits” to reduce the size of the needed solar system. They also include incentives to move away from natural gas to new homes, as well as other efficiency measures.

Once again, California is taking a strong leadership position on the environment that will benefit clean tech deployment and save new homebuyers money in the process. The decision should be a major boost for these needed technologies.

For those attending the Advanced Clean Transportation (ACT) Expo in Long Beach this week, I’ll be presenting this morning on a panel from 10:30am to noon on the prospects and policy needs for repurposing used electric vehicle batteries.

For those attending the Advanced Clean Transportation (ACT) Expo in Long Beach this week, I’ll be presenting this morning on a panel from 10:30am to noon on the prospects and policy needs for repurposing used electric vehicle batteries.

As Berkeley and UCLA Law covered in our 2014 report Reuse and Repower, used electric vehicle batteries have the potential to provide a lot of inexpensive energy storage:

Assuming 50 percent of the battery packs on the road in 2014 can be repurposed, with 75 percent of their original capacity, these second-life batteries could store and dispatch up to 850 megawatt hours of electricity (one megawatt hour is roughly equivalent to the amount of electricity used by about 330 homes over one hour). The aggregated capacity is also equal to 425 megawatts worth of power (one megawatt can provide sufficient power in any given moment to approximately 750 households) – almost one-third of the energy storage capacity that utilities are required to procure by 2020 under a recent California mandate.

Holding this market back from developing are factors such as uncertainty about second-life battery value, complex and adverse regulatory structures, liability concerns about which entity is responsible for second-life batteries, and lack of data about battery performance in both first and second life applications.

Key solutions include:

- Improved and expanded second-life battery pilot projects to demonstrate market potential;

- An industry-led regulatory working group to identify and address regulatory conflicts and needs that limit market development;

- Industry-developed technical performance standards for second-life battery certification that policy makers can use to clarify product liability; and

- Increased funding and incentives for data collection and dissemination on second-life battery projects.

More details can be found in our report and at the Expo, which promises to host some interesting discussions and off-site tours all week.

With Republicans in control of the federal government, climate advocates have looked to the states to make progress reducing greenhouse gas emissions. From my perspective, this is a positive and much-needed approach to climate action, given how relatively weak federal efforts on climate have been, even when Obama as president.

With Republicans in control of the federal government, climate advocates have looked to the states to make progress reducing greenhouse gas emissions. From my perspective, this is a positive and much-needed approach to climate action, given how relatively weak federal efforts on climate have been, even when Obama as president.

Progressive states can move much more aggressively and help pioneer policies and programs that can then become a model for the U.S. as a whole. And in the meantime, they can help bring down the costs of clean technologies like solar and electric vehicles, just through their market power. We’ve seen this play out in California.

But ClimateWire reported [pay-walled] that many of these state policy efforts are languishing, particularly the push to implement carbon pricing (through a carbon tax or cap-and-trade program):

Environmentalists have little hope of passing a proposed $35-per-ton carbon tax in New York, where Republicans control the state Senate. Connecticut and Rhode Island both have proposed enacting a $15-per-ton carbon tax, but only after Massachusetts acts. Massachusetts and Vermont both have Republican governors who acknowledge climate change, but are cool to the idea of a carbon tax.

Even in Oregon and Washington, states where the prospects for a carbon price may be best, climate hawks face long odds. Short legislative sessions and entrenched opposition to a cap-and-trade program in Oregon and carbon tax in Washington complicate the outlook for both proposals.

My question is: why are climate advocates focusing on carbon pricing in the first place? Nobody really likes tax increases, and the fight over what to do with the revenue seems to be dividing people. And in the bigger picture, a price on carbon may be less important at this stage of the climate fight than just getting these clean technologies to scale. After all, once renewable energy, zero emission vehicles, and other needed technologies are cheap, a carbon price should be much easier to implement, politically speaking.

I would prefer the focus at the state level be on setting strong greenhouse gas emission reduction targets through law, empowering key state agencies to achieve the targets (as happened in California), and boosting policies that help deploy clean technologies, such as electric vehicle incentives, aggressive renewable energy and energy storage mandates, and energy efficiency standards for new and existing buildings.

Once progress is made on these fronts, these states will have built up clean tech industries and the resulting political will needed to price the dirtier alternatives.

California Goes Green is a self-published 2017 book that provides an overview of California’s history of climate leadership, including some anecdotes on key policies and the leaders who helped develop and implement them. It was written by two longtime energy policy leaders with first-hand perspectives: Michael Peevey, former president of the California Public Utilities Commission and energy executive, and Diane Wittenberg, who has been involved in electric vehicle policies since the 1990s and in the utility world before that.

California Goes Green is a self-published 2017 book that provides an overview of California’s history of climate leadership, including some anecdotes on key policies and the leaders who helped develop and implement them. It was written by two longtime energy policy leaders with first-hand perspectives: Michael Peevey, former president of the California Public Utilities Commission and energy executive, and Diane Wittenberg, who has been involved in electric vehicle policies since the 1990s and in the utility world before that.

Peevey and Wittenburg are therefore well positioned to describe this history, and their book focuses largely on California’s efforts to decarbonize the electricity and transportation sectors. It touches on renewable energy, energy storage, energy efficiency, and electric vehicle policies, preceded by some general environmental and cultural history in the state.

Overall, California Goes Green provides a brisk (142 pages, including an epilogue) overview of why Californians care about the environment, dating back to battles to reduce smog in Los Angeles after World War II. The authors recount how the state’s culture and politics was shaped by the work of universities, business leaders, and policy advocacy organizations to bolster policy and technology responses to environmental challenges.

The highlights of the book include some interesting anecdotes on some of Peevey and Wittenberg’s topics of expertise, like the 2000-01 state energy crisis, the formation of major environmental agencies in the 1960s and 1970s, the ballot battle over the failed Prop 23 initiative to suspend California’s climate law in 2010, and California’s ultimately successful effort to obtain a federal waiver from the EPA under the Clean Air Act in the 2000s. We also learn some interesting historical tidbits, such as former Governor Schwarzenegger taking an interest in rooftop solar policies because his friend (and movie director) James Cameron had trouble getting approvals for his solar array and called on the governor for help.

But the book offers relatively superficial accounts of some of the most crucial policy battles. Although the authors acknowledge interviews and other communications with key figures involved, the narrative does not feature any direct quotes from those present. Nor do the authors explore in any meaningful depth the various interest group positions and concerns and compromises that went into some of the key policy deals.

There’s also the nagging feeling that the authors are overstating Peevey’s role in some of this history (although he clearly was a central figure on utility regulation and some other policy fronts for an important period of time). For example, at one point the book suggests that Peevey single-handedly was responsible for bringing to California the idea of installing smart meters, after a trip to a utility conference in Italy. But this sounds a bit far-fetched, given the longstanding and broad-based movement to bring smart grid technology to the U.S. But perhaps that’s an unavoidable drawback of having one of the players on the field write the history of the game.

The authors also represent the book as a guide for other jurisdictions and countries who want to follow California’s policy lead, and it should be helpful in that respect. But they don’t provide readers with a basic overview of what climate policies are needed in a developed economy at a macro scale, like a mini version of the state’s comprehensive scoping plan. As a result, the authors focus the book mostly on electricity and transportation but fail to cover in any real way key climate issues such as transportation infrastructure, land use and sprawl, and short-lived climate pollutants, just to name a few. These are all significant contributors to greenhouse gas emissions and merited more attention in the story.

Despite these shortcomings, the book is useful background for anyone working in climate policy or just wants to know more about California’s efforts to date. It also does a nice job giving credit to some relatively unheralded environmental leaders through various “profile” pages. But we still need a fuller story of how these and other leaders got these landmark policies adopted. These details would be both illuminating and entertaining to read for not just for policy wonks, but for the general public that would benefit from a comprehensive and accessible account of California’s pioneering efforts to combat change.