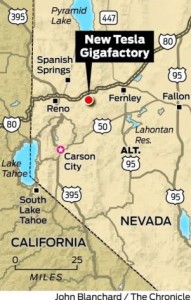

Some California environmentalists may be celebrating now that Tesla has apparently decided to build its $5 billion “gigafactory” in Nevada instead of California. Lawmakers here had toyed with the idea of weakening the state’s signature environmental law, the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), to help expedite review on the factory and therefore encourage Tesla to locate in-state, possibly in Stockton. But those plans fell through last week.

But Tesla’s decision could be an overall setback for the environment, compared to building a factory in California. To be sure, the idea of a gigafactory is a huge win for the environment overall. The cheaper batteries will encourage more adoption of electric vehicles and also help clean our grid by enabling inexpensive storage of surplus wind and solar energy.

So why is Nevada so bad, compared to California? First, the siting of the gigafactory will likely launch a major manufacturing program, with an attendant industry likely to spring up around it, in a state with much weaker regulation than California. Nevada ranked 20th among US states in a George Mason University survey of the most lax regulatory states when it comes to land use decision-making, with California ranked 49th. And a recent comprehensive survey of business owners gave Nevada an “A” on the impact of environmental regulations on business, which is not a good sign for environmental protection. California of course received an “F.” So the factory itself, as well as any future co-located suppliers, will operate with less future oversight for environmental health and safety protection.

In addition, the thousands of workers who will be employed there will likely end up in new subdivisions that sprawl over the high desert countryside, if Reno’s past growth is any indication. And they will likely commute to work by car, a lifestyle that Californians are rapidly abandoning. California meanwhile is engaging in regional transportation plans that will offer alternative, more environmentally friendly housing and transportation for workers, and its environmental laws are now encouraging growth closer to jobs and services.

Finally, from a shipping perspective, the factory in Nevada will have to transport the batteries by train to the major population centers in San Francisco and Los Angeles, which are the leading markets to buy electric vehicles. Locating the factory in Stockton would have reduced this shipping distance significantly, along with its associated environmental impacts, while placing the factory only a negligibly farther distance from the East Coast markets.

Tesla CEO Elon Musk has said that he plans to build more such factories. And as I say, the gigafactory is an overall environmental win. Yet while California’s economy would certainly benefit from locating it in-state, the environment would as well, compared to the site announced today.

Last year, the California legislature passed badly needed reform to change how agencies evaluate a project’s transportation impacts under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). The Governor’s Office of Planning and Research (OPR) was tasked with coming up with new guidelines for how this analysis should be done going forward. As I blogged about, the new proposed transportation metric, vehicle miles traveled (VMT), will inherently benefit infill projects and punish sprawl projects, because infill by its nature decreases VMT.

But you would never know that if you just read the misleading diatribe against the new guidelines by the influential large law firm Holland & Knight. Right off the bat, Holland & Knight attorneys get it wrong on both the legislation and the guidelines:

OPR proposes to dramatically expand CEQA by mandating evaluation and mitigation of “vehicle miles traveled” (VMT) as a new CEQA impact and single out certain infill projects as the first category of projects that must comply with this new VMT regime before it becomes mandatory for all projects in 2016.

In fact, the opposite is true. The guidelines essentially exempt any project within a half-mile of transit — or in areas that are below the regional average VMT levels — from any transportation analysis under CEQA. And lest you think that’s a small area, keep in mind that almost the entirety of urban Los Angeles is within a half-mile of a high quality transit stop, due to the extensive bus network.

A little less of this, please

What OPR is actually doing is eliminating the existing “level of service” (LOS) transportation analysis (which basically means auto delay) from CEQA in infill areas first and statewide by 2016. OPR is then replacing it with a VMT study requirement only in areas with high average VMT. Projects in low average VMT or transit areas either won’t need to do any transportation study whatsoever or won’t need to mitigate at all. That hardly equals an “expansion” of CEQA. Furthermore, the 2013 CEQA legislation specifically required OPR to come up with a replacement for LOS and called out VMT as the most likely substitute.

Holland & Knight attorneys then attempt to scare infill developers and their advocates by claiming that the new metric will lead to additional litigation. First of all, as mentioned, most infill projects won’t even need a transportation analysis under CEQA anymore, eliminating expensive and contentious traffic studies. Second, these traffic studies already trigger litigation all the time under the existing LOS transportation analysis, so it’s not like these guidelines are ruining the wonderful world for infill under the status quo. And finally, and most importantly, the OPR guidelines make lead agency decisions as bulletproof as possible on how to analyze transportation impacts under the new metric. How? By giving lead agencies discretion to pick the VMT model of their choice and to use their professional judgment in applying it to projects. LOS analysis certainly doesn’t have that kind of legal protection, as traffic studies are challenged all the time based on their methodology and assumptions.

But Holland & Knight attorneys protest that lead agencies lack affordable and easy-to-use VMT models, leading to more uncertainty:

[I]t must be acknowledged that we have few, if any, models that purport to be able to accurately characterize VMT at a project-specific level for infill projects. The absence of such models will lead to increased study costs (at a minimum) and litigation/enforcement uncertainty as “NIMBY” opponents will have a new tool to use in CEQA lawsuits aimed at stopping or delaying a project.

The reality is that agencies around the state are using off-the-shelf VMT models all the time, most notably for local climate action plans and for regional plans under SB 375. This is not a new field, and dozens of models exist for lead agencies to use their discretion to use.

Finally, Holland & Knight attorneys complain that the measures required to mitigate high VMT levels “go beyond CEQA’s statutory scope and delve into socioeconomic and land use policy planning issues that the legislature has repeatedly declined to include in CEQA.” I disagree. OPR’s suggested mitigation measures are sensible and targeted to reducing VMT, such as by improving access to transit, providing transit passes and bike-sharing, and reducing or unbundling parking. Ultimately, how else could a project with high VMT mitigate this impact? The goal here, after all, is to reduce driving and to use CEQA as a tool to encourage that reduction where feasible.

It’s unfortunate that Holland & Knight attorneys are attempting to spread this misinformation to their clients and beyond. The state needs to leave behind the old framework of prioritizing autos over transit, bicycling, and walking. At the same time, CEQA should require sprawl project developers to account for their impacts on regional traffic and air pollution. VMT is the most sensible metric to accomplish these goals, and OPR’s guidelines are well thought out, with opportunity for continued refinement from stakeholder input. Yes, it will involve a new framework and some getting used to. Yes, LOS will still exist in some local plans and agency analyses. But this is the beginning of a long overdue transition, and Holland & Knight should cease with the misinformation and let the state move forward.

Back in 2013, there was significant discussion about reforming the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), with the business community and its attorneys arguing that CEQA is nothing more than a litigation tool for opponents of new projects. Some environmentalists and labor unions countered that CEQA is necessary for decision-makers to adequately assess the environmental impacts of new projects and mitigate negative outcomes where feasible.

So of course the result of this debate was to streamline environmental review of a new basketball arena in downtown Sacramento.

But when California legislators passed SB 743 (Steinberg), they included an important provision related to CEQA review of project transportation impacts. Despite CEQA having an “E” for “Environmental,” transportation impacts basically meant auto-delay, or “Level of Service” (LOS). If your project slowed traffic anywhere, that was a negative impact, even if you were building a bus rapid transit line or new infill development that would reduce sprawl and traffic overall. Sprawl projects benefited, and infill and transit was penalized.

SB 743 directed the Governor’s Office of Planning and Research (OPR) to ditch this counter-productive LOS metric for something like a “vehicle miles traveled” standard (SB 743 gave OPR discretion to evaluate other metrics, too). OPR just released their draft proposal for the SB 743 guidelines and has settled on VMT.

Bus rapid transit shouldn’t get dinged for slowing cars

Why VMT? In short, the overall goal of our development patterns should be to provide housing, jobs and retail/services within convenient access of each other, without forcing long and frequent drives and creating more pollution. If we can reduce traffic overall, we’ve succeeded. VMT is the best and simplest metric to determine progress. Free VMT calculators exist, and many lead agencies already use it to calculate greenhouse gas emissions from projects.

Under the new proposed guidelines, OPR directs lead agencies to find less than significant transportation impacts if a project is located 1/2 mile from high-quality transit or in areas of less than the regional average for VMT. Local governments can set more stringent requirements if they want, but this will be the new floor. By 2016, OPR will phase in this standard across California, not just in infill areas.

The statute — and OPR — is basically trying to give infill projects a pass on transportation impacts under CEQA, while simultaneously dinging sprawl projects for creating more regional traffic. As Streetsblog LA observed:

When the state measured transportation impacts of a project based on car delay, it was fighting against its own environmental goals. Using LOS, it was easier and cheaper to build projects in outlying areas where individual intersections would show less delay resulting from new development. At the same time it was much harder and more expensive to build in dense areas where there was already a lot of traffic, and where measured LOS impacts would require expensive mitigations or reduced project size — but also where higher density would make transit, walking, and bicycling more viable transportation choices.

Planning expert Bill Fulton also noted:

Almost as bold as the proposal to switch to a VMT standard is OPR’s suggestion that expanded roadways in congested areas – currently often a mitigation under CEQA – should actually be examined as a possible growth-inducing impact under CEQA.

So while the focus now is on making infill projects easier to get entitled, the real action will be to slow or stop sprawl projects under CEQA, using the new VMT provision. Perhaps that’s why the big builders are worried about this change to VMT. In any event, the guidelines are not final, and OPR welcomes comments, which are due by October 10th. Yet while we can expect changes, the overall framework of VMT is unlikely to change, for the betterment of the state.

The California High Speed Rail Authority secured a big legal victory in the state court of appeals yesterday, which overturned twin decisions by a trial court judge that threatened to derail (no pun intended) the entire program. Coupled with another appellate court win a week ago upholding the program-level environmental review on the Pacheco Pass alignment to the Bay Area, along with approved cap-and-trade funding for the system, the High Speed Rail Authority is on a roll this year (see James Fallows’ positive take in the Atlantic last month, which featured a nice shout-out to UCLA/UC Berkeley Law’s 2013 report on high speed rail and the San Joaquin Valley). However, while the victories allow the project to proceed and maybe even finally achieve that oft-delayed groundbreaking later this year, they don’t mean the end of legal challenges.

First, the good news for high speed rail supporters. The Appellate Court overturned two decisions by the trial court judge, Michael Kenny (I blogged about them back in November). In the first part of his November decision, Kenney had ruled that the state committee that approved the disbursement of bond money for the project acted without sufficient evidence to justify the disbursal.

First, the good news for high speed rail supporters. The Appellate Court overturned two decisions by the trial court judge, Michael Kenny (I blogged about them back in November). In the first part of his November decision, Kenney had ruled that the state committee that approved the disbursement of bond money for the project acted without sufficient evidence to justify the disbursal.

This decision (to me) represented judicial micro-management of what should really be a simple approval. The appellate judges apparently felt the same, unanimously concluding that “the highly unusual scrutiny” by the trial court in this instance should be overturned. Otherwise, it could set a precedent that “jeopardizes the financing of public infrastructure throughout the state.” In my view, this was the easier of the two calls.

Kenny’s second decision against high speed rail related to the draft business plan that the High Speed Rail Authority submitted to the legislature before that body approved the sale of the bond funds in 2012. The business plan was pretty plainly inconsistent with the ballot initiative language that voters approved in 2008 to authorize the bond issue. Kenny wanted the Authority to redo the business plan, as well as its environmental review under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA).

However, the appellate court overturned this decision, too, concluding that since the legislature approved the bond sale based on this draft plan, it effectively deemed the plan sufficient, even if it really wasn’t. Regardless of the adequacy of the business plan, the court did not want to second guess the legislature and risk raising separation of powers issues among the branches of government. Ultimately, the court described the flawed business plan as really just an intermediate, advisory plan for the benefit of the legislature in making the decision to authorize bond sales. The final funding plan that will come out in a few years is where the real judicial scrutiny will come, according to the court.

But of course in a few years, with billions of dollars spent on a line under construction, the courts are unlikely to get in the way of the project going forward. So this appeal was effectively the last hurrah for high speed rail opponents to stop the system entirely.

We can still expect much more litigation going forward, particularly on relatively small-scale route selection issues and mitigation measures. The Pacheco Pass decision represented a partial loss in this respect: the court in that case rejected the Authority’s contention that CEQA is preempted by federal law, keeping the door open for literally hundreds of CEQA lawsuits from every group with an axe to grind or a property affected in the coming years.

But the big show is now over, and high speed rail can get on with being built. Of course the Authority only has enough money to begin its initial section in the Central Valley and maybe over to the Antelope Valley. So finding an ongoing funding source will remain a hurdle. Lawsuits over route selection could complicate matters by driving up costs through expensive mitigation measures or route changes. Meanwhile, trial courts will scrutinize environmental review and the final funding plan, once it comes out.

Ultimately, the Authority will continue to have its back against the wall trying to comply with the highly detailed and prescriptive 2008 ballot language, which makes the political and financial wheeling-and-dealing necessary on big infrastructure projects difficult (as intended). But if courts like this one are going to be sympathetic to those political and financial pressures, then the Authority — and California travelers — may have a smooth ride ahead, at least as far as judicial oversight goes.

Western states like California are falling all over themselves to secure Tesla’s proposed “gigafactory” to mass-produce lithium ion batteries. This cheap energy storage will be a game changer for making electric vehicles affordable and decarbonizing our electricity supply by balancing intermittent renewables from the sun and wind. But for state leaders, the factory means great middle class jobs in an expanding clean-tech industry.

Texas seemed to have the lead, but California is pulling out all the stops, including waiving key environmental laws like the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). Now it appears that if the factory happens in California, it may be in Stockton, according to the Los Angeles Times. Stockton is just an hour outside of the Bay Area in the Central Valley, with many people commuting into the Bay Area there from cheaper middle-class sprawl developments. Plus it has access to waterways, freeways, and the Tesla vehicle factory.

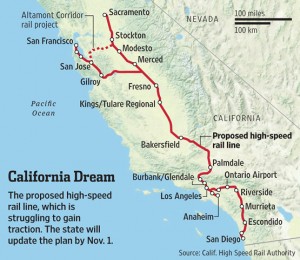

But if the factory does happen in Stockton, it should also have access to high speed rail. A decision to locate the gigafactory there should prompt the California High Speed Rail Authority to reconsider its proposed route to the Bay Area from the south via Pacheco Pass and pristine, rural San Benito County. That route is not my favorite — it cuts off major population centers, including Stockton and Modesto, and puts a beautiful, undeveloped part of the state at risk of rail-induced sprawl. It does serve San Jose more directly, but the city could still be served by a spur from an Altamont route. Here’s the current proposed route:

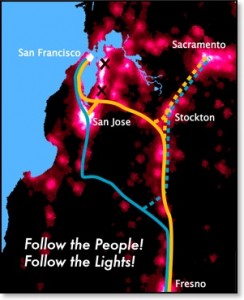

And here’s the alternative Altamont Pass route that would provide access to Stockton and the possible factory (source is the advocacy group Transdef):

And here’s the alternative Altamont Pass route that would provide access to Stockton and the possible factory (source is the advocacy group Transdef):

The Authority just won a CEQA case on appeal upholding environmental review on the Pacheco alignment. But maybe the prospect of the gigafactory, combined with the other benefits of routing the system along Altamont, will prompt long-overdue reconsideration.

The Authority just won a CEQA case on appeal upholding environmental review on the Pacheco alignment. But maybe the prospect of the gigafactory, combined with the other benefits of routing the system along Altamont, will prompt long-overdue reconsideration.

Tesla’s proposed “gigafactory” to mass produce cheap lithium ion batteries could be a climate game-changer. The batteries would be an environmental twofer: first, we’d get cheap electric vehicles to dramatically reduce transportation emissions (via a half-priced Tesla), and two, we’d get cheap energy storage units that could be used for everything from home and business backup or offgrid power to utility-scale storage of renewable power, which could be dispatched when the sun isn’t shining or the wind isn’t blowing. It’s the missing piece to achieve the worldwide reductions in greenhouse gases needed by 2050, which require electrifying transportation and simultaneously decarbonizing our electricity supply.

It also means a lot of jobs for whatever state gets the factor. California was considered out of the running, but state leaders have been lobbying Tesla CEO Elon Musk big-time. And now we can see some of that wining-and-dining in legislative action. SB 1309 (Steinberg & Gaines) provides a legislative commitment to reduce regulatory barriers to siting the factory, including environmental review under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA).

Big project streamlining like this has happened before, most notably for large sports facilities like the Sacramento Kings arena and an NFL stadium in downtown Los Angeles. But this would be the first time that a facility with such huge environmental benefits would get an environmental review exemption (or streamlining, depending on how the bill gets worded). If it comes to pass, it will likely pit traditional environmentalists against climate hawks. But first we’ll have to see what Musk decides to do with the facility. Stay tuned!

Robert Cruickshank over at the California High Speed Rail blog took issue with my call for political reform to ensure that rail routes, including high speed rail, are as cost-effective and efficient as possible, as defined by maximizing ridership. Actually he never disagreed with my calls for political reform because he evidently never made it to the end of my blog post. Once I criticized the high speed rail route (as evidence for the need for said political reforms), he apparently stopped reading further and took to Twitter to denounce the post.

I argued in the post that California’s highly decentralized system of government leads to political compromises that undermine the effectiveness of rail routes, including high speed rail. This is what set off Cruickshank, who runs a blog supporting high speed rail. As a result, he never addressed the multiple examples I gave of inefficiencies based on political compromise in the LA and Washington, DC rail systems.

But he did take issue with my assertions about the politically motivated inefficiencies of the high speed rail route. I call them “inefficiencies” because they hurt system ridership. The basic idea is that we maximize high speed rail ridership by having the fastest travel time between the two major population centers in the state — Los Angeles and San Francisco. Any changes from the most direct route possible need to be justified based on ridership increases elsewhere.

Right off the bat, Cruickshank seems confused about how best to maximize high speed rail ridership. “Elkind cannot decide whether he supports increasing ridership overall, or just getting from SF to LA as fast as possible regardless of the consequences,” he writes. But these are not mutually exclusive concepts. High speed rail should serve the highest population centers in the most efficient way possible in order to maximize ridership.

So here are my three examples of high speed rail route changes that were done for political — not ridership — reasons:

- The Pacheco Pass alignment via San Benito County instead of the Altamount Pass along I-580;

- The Palmdale/Mojave Desert alignment instead of the Tejon Pass by I-5; and

- The eastern Highway 99 San Joaquin Valley route instead of along I-5 in the Valley.

All three routes were designed to serve important political constituencies but not necessarily to serve the maximum number of riders.

Of the three examples, Cruickshank ignored the Palmdale example completely, I assume because it so clearly proves my point and undermines his. Instead, Cruickshank attacked me for arguing against the Pacheco and Valley alignments.

On Pacheco vs. Altamont, Cruickshank is simply wrong. The alternate Altamont alignment would serve more people and provide faster service to San Francisco. It also allows faster service to Sacramento from San Jose and Los Angeles. Cruickshank never addressed those points and instead fixated on how the Altamont route would “skip” San Jose. But a spur line to San Jose fixes that problem and leads to faster service to Sacramento from San Jose and Los Angeles. I don’t see any reason for an overall ridership drop-off with the spur, as Cruickshank fears, especially since it does not preclude electrifying CalTrain to San Francisco and achieving the same medium-speed service already projected for that corridor now. And meanwhile you get the ridership benefits of faster service elsewhere for more people.

Next he attacks me for the criticizing the Valley route, and here is where it gets more complicated. To be clear, I stand by my argument that the Valley section was politically chosen, although the greater tragedy is that Valley representatives forced the system to begin there in no-man’s land, leading to a system that will be useless for most Californians for decades to come.

Yet despite the unsavory political origins, I actually agree with this route choice. Cruickshank describes me as inconsistent here but never asked for my rationale (it wasn’t the point of my blog post so I never spelled it out). I support high speed rail serving Valley cities like Fresno and Bakersfield, despite slowing the San Francisco to Los Angeles route. Why? Because the Valley is the fastest-growing part of California, with long-term population growth projections that would lead to high ridership in the future, and because of the value of connecting medium-distanced cities like Fresno to L.A. and San Francisco, which are too close to fly but too far to drive conveniently. System ridership overall should benefit in the long-term from this route and make up for lost ridership from the slower service between San Francisco and L.A.

I suppose this is an instance where political negotiations unintentionally produce an acceptable result, although it’s still ‘no way to run a railroad.’ As an aside, you could make a similar argument about Henry Waxman’s opposition to the L.A. Metro Rail as actually producing a positive result: faster service between Hollywood and downtown Los Angeles. Although it doesn’t justify skipping the Wilshire corridor in Los Angeles.

But even with the Valley alignment, we run the risk that growth-inducing impacts from high speed rail will encourage Los Angeles-like sprawl that will undermine ridership, worsen air quality, chew up open space and farmland, and destroy the point of the system. That prospect reinforces the need for the political reforms I recommend, particularly regarding density requirements for selected routes.

But then Cruickshank begins arguing with me over something I never said or believed:

Elkind’s post falls into the rather common trap of believing that if the California High Speed Rail Authority had just made different route choices, all would be well. The problem is that his recommendations are contradictory, and even if adopted they’d do nothing to improve the project’s political fortunes.

I made no such claim that my recommendations would solve the high speed rail political problems. Precisely the opposite: I was showing how in our current system these kind of negative compromises are required to build a train like high speed rail. My recommendations, clearly stated at the bottom of my post, have nothing to do with route changes and everything to do with political reforms to ensure that we get the best rail route for our money. Cruickshank never addressed those recommendations, which call for density requirements on the route, litigation restrictions, and campaign finance reform.

But his primary interest seems to be to insist that planners, not voters or elected officials, have the final say on what goes where.

Again, Cruickshank puts words in my mouth. My primary interest is having the most efficient HSR service possible. We need to reform our decentralized political process that empowers random elected officials to twist the route over the one that benefits the most people. And part of that decentralization comes from the legal system, with ongoing court challenges to the best routes.

Ultimately, Cruickshank doesn’t seem to think we need any political reforms, although he never addressed the ones I recommended:

California’s democratic processes have produced repeated support for the bullet train. Those who oppose the train have had to resort to end runs around the democratic process, primarily by going to court to try and reverse the decisions of the voters and their legislators.

I assume he’s referring to the ballot initiative in 2008, which would not pass today, and the Legislature disbursing the funds, which required a significant amount of arm-twisting. With these examples, Cruickshank does not grapple with my point about project implementation: when it comes to actually building and routing the projects, it’s horse-trading and arm-twisting every time, and the public loses. The result is a less-efficient system that wastes money, time, and opportunities for the millions of people who could otherwise be benefiting from the system.

Cruickshank is clearly a cheerleader for the system route as it currently stands. And high speed rail clearly needs cheerleaders like Cruickshank. But sometimes advocates have stronger positions if they are willing to admit — and work to correct — obvious flaws.

Americans seem to love democracy but hate many of the results. We want governmental power to be decentralized, whether it’s across three federal branches or with local control over sometimes regionally oriented land use decisions. But when the inevitable compromise that is required to get majority approval means a less-than-perfect result, from Obamacare to budget deals, or when it means no results at all, such as congressional gridlock, we complain and threaten to vote out our under-empowered representatives.

Perhaps no policy initiative more starkly demonstrates the challenges of democracy than rail transit. After all, when congressional leaders compromise on a farm bill or Obamacare, the results are often invisible to many of us. We know some people may not get health care or food stamps, we see the statistics, and we may know some of the people affected. But on the whole, the effects of compromise often feel abstract.

But with modern rail transit lines, you can actually see the ill effects of compromise. The rail route may serve some head-scratching neighborhoods that don’t seem to merit access — or stop short of others that do. With the Los Angeles subway, the route along the densely populated Wilshire corridor takes an unfortunate turn north to serve areas of political power and less ridership, when it should have continued straight to Westwood. Or as Zachary Schrag described in Great Society Subway, the Washington D.C. Metro has two Farrugut stations right next to each other on different lines (Farrugut West and Farrugut North) all because the rail agency couldn’t get permission from the federal government to put a single, convenient station in the middle of a Farrugut Square.

But with modern rail transit lines, you can actually see the ill effects of compromise. The rail route may serve some head-scratching neighborhoods that don’t seem to merit access — or stop short of others that do. With the Los Angeles subway, the route along the densely populated Wilshire corridor takes an unfortunate turn north to serve areas of political power and less ridership, when it should have continued straight to Westwood. Or as Zachary Schrag described in Great Society Subway, the Washington D.C. Metro has two Farrugut stations right next to each other on different lines (Farrugut West and Farrugut North) all because the rail agency couldn’t get permission from the federal government to put a single, convenient station in the middle of a Farrugut Square.

High speed rail offers further examples. For political reasons, the California line is routed to serve the 99 corridor in the eastern San Joaquin Valley over the more direct western Interstate 5 route, all at the behest of congressional representatives and local Valley officials. And then the system serves the Lancaster/Palmdale area in the Mojave Desert area of northern Los Angeles County in order to please a powerful member of the five-seat county board of supervisors. Both route changes cost travel time between the state’s major population centers and have engendered local opposition partly as a result. Meanwhile, the wealthy residents of San Francisco peninsula towns that don’t want a high speed train near their backyards are bankrolling legal opposition.

Even high speed rail in other countries suffers from this dynamic: the German high speed rail system is slower than the adjoining French one, in part because of German federated politics. “Unfortunately the trains have to stop for every mayor,” explained Peter Mnich, one of Germany’s leading rail experts and a professor at Berlin’s Technical University. German high speed rail even stops at cities with populations as low as 12,518, whereas France’s more centralized political system enabled efficient nonstop routes that out-compete airlines in the same travel corridors.

Worse, the democratic decision-making process leaves these systems open to charges of undue special interest influence via campaign contributions. Downtown business leaders in both San Francisco and Los Angeles, which contributed mightily to political campaigns, were instrumental in getting rail systems in those cities launched, primarily to boost their real estate values (it worked in both cases). Freight railroads bankrolled the campaign for a 1990 rail sales tax measure in Los Angeles, hoping it would pass and that the county would then have money to buy surplus rail rights-of-way (it did and it did). Contractors building the L.A. subway made major campaign contributions to local officials who awarded rail contracts and prosecuted (or not) workplace safety violations. Labor unions helped support the 2008 sales tax initiative because their members would make money building the system.

So what can be done? Few Americans would want to impose Chinese-style decision-making in our lives. We respect private property rights in this country and believe it’s important to have many voices at the table. But since when did we start deferring to the needs of a few at the sacrifice of the many? With rail projects, that dynamic unfortunately seems to be the norm. Some policy remedies to consider:

- Federal and state requirements that transit dollars can only be spent on routes and stations in the highest-density corridors and areas;

- Legal protection for rail (and rapid bus projects) from the kind of lawsuits typically brought by well-funded neighborhood groups; and

- Campaign finance and decision-making reform of rail agencies to ensure that they are not unduly influenced by special interests. One fix in a place like Los Angeles would be to replace elected officials on the transit agency board with appointees who don’t campaign. Or have agency directors decided through county-wide or district elections with full campaign cash transparency.

In the early twentieth century, it seems like we were better at getting these critical infrastructure projects built, and we still had a democracy then. Not to pine for the good old days, which were fraught with other problems, but it may be necessary to roll back the clock in some ways, like resurrecting appointees to transit boards and shielding agencies from lawsuits. At the same time, we can use cutting-edge data and modeling techniques to choose the best routes and stations. These reforms could re-balance democracy and rail planning and ensure that democracy is not just “the loudest voice in the room wins.”

Otherwise, the status quo, to paraphrase Yogi Berra, just ain’t what it used to be.

Smart growth advocates are lamenting a judge’s decision yesterday to toss out the environmental impact report (EIR) on Hollywood’s years-in-the-making plan for higher-density growth around the city’s subway stops. Hollywood is one of the few communities in California willing to increase growth around transit stops and along transit corridors, and the demand for housing and office space there is apparently sufficient to accommodate new development without the need for public subsidies. So in some ways it was a sad outcome that the city’s plan failed in court. Los Angeles — and the rest of California — needs cities to step up and zone for compact development around transit, or else we are doomed to a future of more sprawl along the urban fringe and a perilous mix of high housing costs and increasing inequality in the urban core.

But the decision against Hollywood was not about stopping smart growth — it was about a bad EIR. Hollywood had relied on outdated population figures in trying to comply with the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), which required the EIR. The 2010 census data were released just before the draft EIR, with figures that dramatically departed from the original population estimates and projections. Yet the city refused to modify its EIR (perhaps understandably, as it would have meant throwing out years of work). But without updated population figures, its assessment of basic impacts from growth on the water supply, sewer system, and electricity usage, among other areas, was fundamentally flawed. Surely even smart growth advocates see the need for accurate infrastructure assessment and planning. Without it, infill projects are bound to run into complications during construction and/or operation.

Yet while I see the value of CEQA review for infrastructure-type impacts from infill plans, I wonder how well CEQA functions in general for infill specific and community plans. For example, analyzing parking and traffic impacts can be counter-productive for an infill plan. More infill by definition creates more parking and traffic problems in that immediate area. However, infill reduces regional parking and traffic problems, which is not often credited in an EIR (recent legislation may change that dynamic, at least for transportation impacts). Similarly, an alternatives analysis that doesn’t account for the regional alternative may also fail to assess how one city’s infill plan can benefit the whole region. After all, where will future residents who would have lived in downtown Hollywood buy or rent homes if there aren’t options in the urban core going forward? Most likely they will have to live farther away from their jobs, leading to lost open space from development pressure, worse air quality, and more traffic congestion. This is the consequence of making infill harder to build.

Hollywood now has an opportunity to revise its EIR with more accurate population figures and create a monitoring program for future development, as required to be consistent with the Los Angeles general plan. I hope these revisions will not be too onerous and that the City can fulfill its vision to build around the multi-billion subway network its lucky to have. But going forward, policy makers at the state level may need to take a serious look at how CEQA can better help cities plan for infill. Analyzing more impacts at the regional scale — or not at all in some cases — may make the most sense if we truly want to accommodate future growth in our cities instead of on our open space and agricultural land.

California Superior Court Judge Michael Kenny dealt two setbacks to high speed rail yesterday that are likely to delay the project significantly. First, Judge Kenny ruled that the state committee that approved the disbursement of bond money for the project acted without sufficient evidence to justify the disbursal. California law empowers the High-Speed Passenger Train Finance Committee to authorize the release of $8 billion of the bond funds that voters approved in 2008 for the project. The High Speed Rail Authority requested this authorization earlier this year to begin work on the project. But Judge Kenny ruled that the finance committee essentially acted as a rubberstamp for the request without justifying the decision with any evidence.

So the committee will now have to reverse engineer its decision with evidence showing that the release of the bond funds is “necessary and desirable” per the language in the voter initiative. Given that the committee’s only justification for its authorization was the Authority’s request itself, it shouldn’t be difficult to come up with something to satisfy Judge Kenny.

However, that effort could be complicated by the second – and potentially more significant – ruling that Kenny issued. That decision came in the remedy phase for Kenny’s August ruling (my blog on it here) that the Authority’s 2011 business plan violated the terms of the voter-approved 2008 bond initiative. While Kenny declined to halt construction or prevent the Authority from using $3.5 billion in federal funds to work on the project, he ordered the Authority to devise a new business plan. Specifically, Kenny wants the Authority to undertake project-level environmental review under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), as required by 2704.08(c)(H) of the bond initiative. Failure to engage in this analysis could result in substantial delays in the project, or even a need to redesign or relocate portions of the project, potentially at great cost to the State and its taxpayers. Streets and Highways Code section 2704.08 is carefully designed to prevent that from happening, but that design is frustrated if obvious deficiencies in the first funding plan are essentially ignored.

It’s hard to argue with that logic, as CEQA was intended for exactly this purpose: to analyze the likely impacts of large public projects and mitigate negative impacts where feasible (the Authority did complete environmental review on the first construction phase but not on the whole project). But the political problem for the Authority is that 1) CEQA review could take years, thus jeopardizing federal funds which have a sunset date, and 2) the potential mitigation measures required by CEQA could involve route changes that could unravel the fragile political coalition the Authority assembled to support the project. For example, a route change to serve Los Angeles more directly through the Tehachapis could cost the project support from Los Angeles County supervisors if it involves skipping a city (Palmdale) that was promised a high speed rail station.

The Authority will likely attempt an end-run around the CEQA requirements. The Authority and the California Attorney General’s office have argued the project may be entirely exempt from CEQA, due to federal preemption. If the Authority is successful with that line of argument, which it will likely pursue more aggressively in response to this decision, it would remove a significant and ongoing hurdle to project implementation (the project would still have to undertake environmental analysis through the less strict National Environmental Policy Act).

So what’s next? The Authority could submit to Kenny’s directive and go back to the drawing board on the business plan and CEQA review, risking the viability of the entire project. Or it could appeal, citing the CEQA preemption argument or some flaw in Kenny’s decision. And regardless of either option, it could begin construction now using federal funds while the court process plays out, hoping that the advent of construction would put political pressure on the court to okay the project in the end.

What’s certain though is that a project that was once slated for groundbreaking this summer is now on the slow track for the foreseeable future.