Under Senate Bill 743 (Steinberg, 2013), California will soon require developers of new projects, like apartment buildings, offices, and roads, to analyze and mitigate the amount of additional driving miles their projects generate. To facilitate compliance with SB 743, some local and regional leaders are considering creating “banks” or “exchanges” to allow developers to fund off-site projects that reduce vehicle miles traveled (VMT), such as new bike lanes, transit, and busways.

Under Senate Bill 743 (Steinberg, 2013), California will soon require developers of new projects, like apartment buildings, offices, and roads, to analyze and mitigate the amount of additional driving miles their projects generate. To facilitate compliance with SB 743, some local and regional leaders are considering creating “banks” or “exchanges” to allow developers to fund off-site projects that reduce vehicle miles traveled (VMT), such as new bike lanes, transit, and busways.

CLEE’s recent report, Implementing SB 743, provides a comprehensive review of key legal and policy considerations for local and regional agencies tasked with crafting these innovative VMT mitigation mechanisms, including:

- Legal requirements under CEQA and Constitutional case law;

- Criteria for mitigation project selection and prioritization;

- Methods to verify VMT mitigation and “additionality”; and

- Measures to ensure equitable distribution of projects.

CLEE will hold a free webinar tomorrow, Tuesday, October 30th from 10-11am to discuss the report findings and answer questions about SB 743 and VMT mitigation strategies. Speakers will include:

- Chris Ganson, Governor’s Office of Planning & Research

- Jeannie Lee, Governor’s Office of Planning & Research

My colleague Ted Lamm and I will also join. You can register for the webinar (hosted on Zoom) and download Implementing SB 743.

The California State Senate Office of Research just released a new report examining data from the state’s transportation department, to find out how the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) affects transportation infrastructure projects.

As you’ll recall, CEQA mandates environmental review for major projects and feasible mitigation for significant impacts. Industry critics often blame CEQA for unnecessarily slowing vital projects.

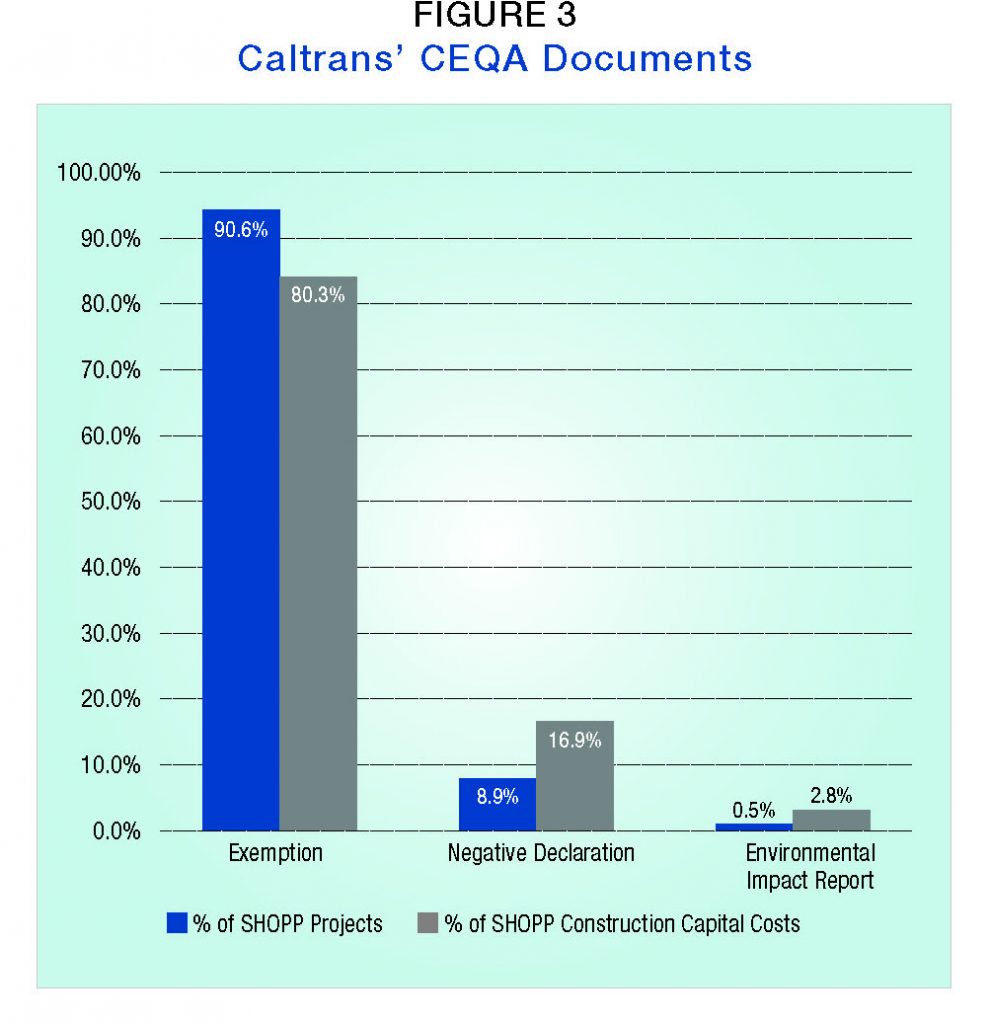

The results from the research? CEQA barely registers when it comes to rehabbing and maintaining transportation projects. As you can see from the chart below, between 80-90% of projects were exempt from CEQA altogether, while only between 0.5 and 2.8% had to undertake full environmental review. The rest received negative declarations of impacts.

The Office of Research obtained the data from Caltrans for 751 transportation projects from the State Highway Operation and Protection Program (SHOPP) program, which prioritizes everything from maintenance to rebuilding bridges. The projects all completed construction in fiscal years 2014 through 2017. The data included information on costs, duration, and the resulting CEQA documents.

The Office of Research obtained the data from Caltrans for 751 transportation projects from the State Highway Operation and Protection Program (SHOPP) program, which prioritizes everything from maintenance to rebuilding bridges. The projects all completed construction in fiscal years 2014 through 2017. The data included information on costs, duration, and the resulting CEQA documents.

Together with an earlier report showing how minimal CEQA litigation is when it comes to state-sponsored projects, plus the Rose Foundation report showing minimal litigation rates statewide, this report is further evidence that CEQA is simply not a major barrier to California’s transportation infrastructure investments.

To be sure, rehab and rebuilding projects are much less likely to face CEQA review issues than a new transportation project (such as high speed rail, which has been the target of substantial litigation). But data like these are helping to paint a clearer context for policy makers who hear anecdotes of CEQA abuse. Because when we start looking at the broader context, CEQA appears to impose relatively minimal costs in the aggregate.

For those interested in the latest legislative updates and debates on housing and land use in California, I’ll be speaking this weekend at the Planning and Conservation League’s annual “Environmental Assembly” conference in Sacramento. I’ll be on an afternoon panel with:

- Kip Lipper, Chief Policy Adviser on Energy and Environment, Office of Senate President Pro Tem Kevin de León

- Winter King, Shute Mihaly & Weinberger, LLP

- Doug Carstens, Chatten-Brown & Carstens, LLP

We’ll discuss recent updates to the California Environmental Quality Act under SB 743, recent legislation like SB 35, as well as pending legislation like SB 827.

More details here:

What: Planning and Conservation League’s 2018 California Environmental Assembly

When: Saturday, February 24, 2018, registration and breakfast starts at 7:30 am

Where: McGeorge School 3200 5th Ave, Sacramento, CA 95817

Last month former California assemblyman John T. Knox passed away at 92. He was a progressive Democrat from Contra Costa County in the East Bay who was the driving force behind the 1970 California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). The East Bay Times has more on his life.

His passing is an opportunity for reflection on the state of CEQA, California’s bedrock environmental law. It’s a perennially controversial topic. Big businesses hate it because they get sued under CEQA and have to build in the litigation uncertainty into their projects as a result. Labor unions love it because it gives them leverage to sue non-union project proponents unless they agree to hire unionized workers. And traditional environmentalists and NIMBYs love it because it gives them leverage over basically any proposed project in the state.

As someone who is motivated to address climate change and boost sustainable housing growth in the state, I’m personally mixed on CEQA. I don’t like its negative effects on infill housing, but I like the basic concept and how CEQA applies to environmentally destructive projects, from certain timber harvesting plans to oil and gas exploration.

On the housing front, here are some truths worth acknowledging:

- CEQA is overblown as a reason for the state’s housing shortage. Developers and their advocates like to blame CEQA for the state’s significant undersupply of housing. But the evidence simply isn’t there that it’s a major cause for suppressing production. For example, the Governor’s Office of Planning and Research survey of planners around the state in 2012 indicated that CEQA was not the prime factor in stopping infill, compared to barriers like local zoning, lack of infrastructure, and public antipathy to new development. And the 2016 survey showed that over 40% of cities and counties in California have successfully used CEQA streamlining for infill projects that might have been subject to the law. Meanwhile, a recent report from the Rose Foundation (on which I served as an adviser) put CEQA litigation in context and found it to be rare. Only 195 CEQA lawsuits on average are filed each year in the state, and fewer than 1 out of 100 projects that aren’t already exempt from CEQA are subject to litigation.

- CEQA does kill or maim a lot of important infill housing developments. Despite the overblown nature of the CEQA claims discussed above, there is still plenty of anecdotal evidence that CEQA has taken out some badly-needed infill projects. The law certainly isn’t designed to help promote more infill housing, and one of the negative aspects not discussed in the Rose Foundation report is the defensive project siting and design that CEQA encourages. And that’s why I’d favor far more limited CEQA review for housing in transit-oriented infill areas.

- CEQA is politically very hard to change at the state level right now. The combination of labor union and traditional environmentalist support for CEQA means that wholesale change at the state level is unlikely to happen soon. Rather, progress will be marked incrementally, such as through SB 743, which essentially removes transportation as a CEQA impact for infill projects near transit and simultaneously requires rigorous analysis for outlying sprawl projects.

Knox left this state an important legacy on environmental protection. But just as courts have vastly expanded CEQA’s reach, a new era of housing shortage and climate change mitigation will require updates to the law to address these modern challenges. As we think through policies needed to boost infill housing, policy makers will need to consider options to streamline CEQA further for these priority needs.

Pretty much everything boils down to land use, at one level or another. Certainly housing and office development is traditionally within that sphere, but so is energy development, when we think about siting new transmission lines or solar farms. Even electric vehicles involve permitting and siting public charging infrastructure.

Tonight on City Visions, KALW 91.7 FM, I’ll talk with Ken Alex, Governor Brown’s senior adviser and director of the Governor’s Office of Planning and Research (OPR), which helps the state set land use policy. We’ll talk transportation, housing policies, water, and climate change. And beyond local government matters, Ken also helps the state with its international climate efforts like the Under 2 MOU.

Tune in or stream at 7pm tonight, and please send in your questions or comments for Ken to address on the air.

UPDATE: audio available here.

The law firm of Holland & Knight has made waves over the past few years attempting to quantify how bad CEQA has been for pro-environment projects like infill and renewable energy. Their allies in the business community and Sacramento, along with unwitting media outlets, have trumpeted the results.

They are now out with a new “update” [PDF] on their flawed 2015 study that purports to show how CEQA has been overwhelmingly used against infill in the Southern California region.

But the problem, as I and my colleague Sean Hecht at UCLA Law have noted, is that they misleadingly chose a definition of “infill” in that 2015 study (and again in this update) that is so broad that it over-represents how often infill projects are subject to CEQA suits, out of all CEQA litigation in a given time frame.

Misleading may be a strong word, but how else can you explain it when they claim to be using a state-approved definition of infill that doesn’t in fact match their definition?

Here’s what they write:

In our [2015] statewide report, we called these “infill” locations, consistent with the infill definition used by the Governor’s Office of Planning & Research (OPR).

And here’s the definition they use:

[Projects] located entirely within the boundaries of existing cities or in unincorporated county locations that were surrounded by existing development.

Yet in their own footnote to OPR’s definition, we find the following from OPR:

“The term “infill development” refers to building within unused and underutilized lands within existing development patterns, typically but not exclusively in urban areas. Infill development is critical to accommodating growth and redesigning our cities to be environmentally and socially sustainable.”

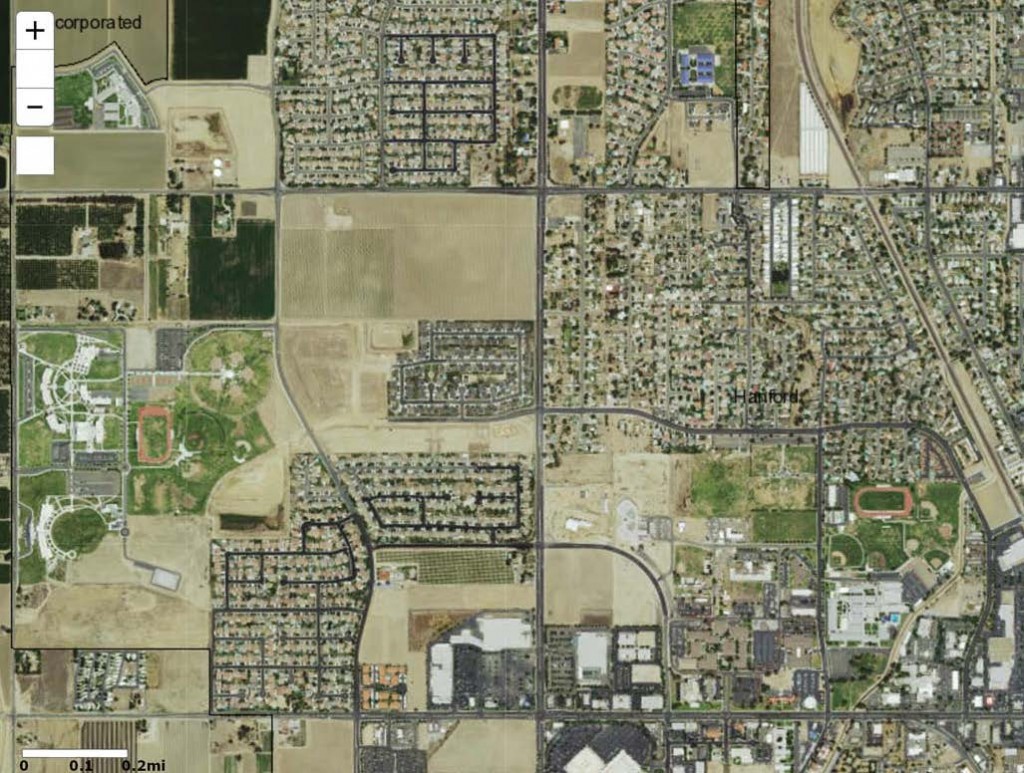

Notice any inconsistencies? Nowhere does OPR claim that any development within existing city boundaries should be considered infill. Yet that’s exactly what Holland & Knight claim their definition encompasses. By adding that geography to the definition, they get to call areas like in this random screenshot of Hanford “infill”:

If they really want to update their study, they need to stop claiming that they’re using a state-sanctioned definition of infill. Because they’re not.

Here’s another definition they could have used, that was added to CEQA by the legislature:

21061.3. Infill site means a site in an urbanized area that meets either of the following criteria:

(a) The site has not been previously developed for urban uses and both of the following apply:

(1) The site is immediately adjacent to parcels that are developed with qualified urban uses, or at least 75 percent of the perimeter of the site adjoins parcels that are developed with qualified urban uses, and the remaining 25 percent of the site adjoins parcels that have previously been developed for qualified urban uses.

(2) No parcel within the site has been created within the past 10 years unless the parcel was created as a result of the plan of a redevelopment agency.

(b) The site has been previously developed for qualified urban uses.

The report does go to some length to describe the challenges of defining infill for the purposes of a study like this one. Personally I favor a definition linked to proximity to major transit stops, coupled with the definition Deborah Salon formulated in 2014 for the California Air Resources Board [PDF] based on low-vehicle miles traveled (VMT) neighborhood types.

But by misrepresenting their definition of infill, Holland & Knight undermines the credibility of their report and the quality of the findings. If they issue any further “update” to it, I hope they finally correct that flaw.

We hear a lot about CEQA abuse, but maybe it’s time for a new term: “CEQA study abuse.”

As I blogged previously, the law firm Holland & Knight issued a report attempting to document how the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) undermines environmental goals. I certainly share the concern of many industry actors and their representatives at law firms like Holland & Knight that CEQA is sometimes counter-productively used against meritorious projects, particularly infill development. And that’s why I’ve supported reforms to the law that help environmentally beneficial projects, such as those that lower overall driving miles and are located near high-quality transit. SB 743 (Steinberg, 2013) is the perfect example of this approach.

But the Holland & Knight study, which tracked litigation records (notably leaving out other ways that CEQA affects project approvals, both good and bad) used an overly broad definition of infill that inflated the results. My UCLA Law colleague Sean Hecht exposed the flaw in this post.

But then Don Perata, former state senate president, came to Holland & Knight’s defense. Perata represents an organization called the “California Infill Builders Federation,” but his arguments support anything but infill. His post on the political site Fox & Hounds didn’t try to rebut Sean’s points but instead misrepresented them, as Sean described in his counter-response.

Bottom-line: the “Infill” Federation is apparently comfortable with a definition of infill that includes all projects located within the boundaries of every city in California, including some county locations. For a visual representation of what that means, here’s the map of incorporated California cities:

For a closer look, here’s incorporated Orange County, which essentially covers the entire jurisdiction not on a mountain or a military base:

For a closer look, here’s incorporated Orange County, which essentially covers the entire jurisdiction not on a mountain or a military base:

And even closer, here’s a supposedly “infill” area in incorporated Hanford in the San Joaquin Valley:

Most of these areas should fit no one’s definition of “infill,” and the report authors should correct that labeling in the study. Relaxing CEQA requirements in these outlying areas would only benefit sprawl and hurt efforts to promote infill-friendly policies.

Most of these areas should fit no one’s definition of “infill,” and the report authors should correct that labeling in the study. Relaxing CEQA requirements in these outlying areas would only benefit sprawl and hurt efforts to promote infill-friendly policies.

Furthermore, as Sean originally noted, this CEQA “study” should not be the basis of any policy making. I hope Sacramento decision-makers are paying attention, because this book should definitely not be judged by its cover.

Yesterday I had a chance to talk to Damien Newton at Streetsblog California for his podcast #DamienTalks about the changes underway to the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) on transportation analysis. Damien is particularly interested in the California Infill Builders Federation opposition to the change from auto-delay to vehicle miles traveled, so we discussed the politics around their legislation to halt the change:

Today #DamienTalks with Ethan Elkind, about the efforts to reform how the state measures transportation impacts of a proposed project. Currently, the state measures how a project impacts car travel time, but a change to state law will turn that rule on its head so that we’re encouraging projects that don’t produce more car trips instead of just mitigating the ones that do.

Not surprisingly, there is pushback. Surprisingly, it’s coming from a group that should gain from the change from “LOS” to “VMT.”

You can access the podcast here or via Damien’s site linked above.

Some local officials in Los Angeles may be sad that developer AEG is abandoning its dream of a downtown football field. The future Farmers Field was supposed to solidify the emergence of downtown Los Angeles as a destination and boost ridership on game days from the adjacent rail lines.

Public officials were very supportive. State lawmakers gave AEG a pass on environmental review under the California Environmental Quality Act (technically AEG received an accelerated judicial process with agreed-upon, stringent mitigation measures).

From a transit perspective, the news isn’t great. The two other football stadium options in Los Angeles are fairly far out there, with one in Carson and another in Inglewood. These locations are not nearly as centrally located as Farmers Field would have been in terms of rail service and walkability.

But ultimately this may be a bullet dodged for Los Angeles. Football fields are generally a waste of valuable downtown real estate. There are only eight home games a year in the National Football League, and maybe two pre-season games. 10 games out of 365 days? That’s a waste of space for the vast majority of the year.

Sure, the venue can also host soccer games, concerts and maybe some giant outdoor conventions, like if the Pope ever visits. But most of the time it would be idle.

If you’re going to build a sports stadium downtown, it really should be for baseball. You get 81 home games a year with baseball, which means a lot of days and nights with thousands of pedestrians streaming in and out of local shops. Baseball also attracts a more mellow crowd than football, in my experience, so you don’t have the same “drunken brawl” factor (notwithstanding some recent high-profile incidents of baseball fan rage).

Hopefully AEG will find a much better use for that huge parcel downtown. Studies seem to support the idea that more housing, office and retail gives you a better bang for your buck, in terms of economic development and ridership.

In the end, downtown LA will probably come out farther ahead without Farmers Field.

It’s been over six years since California voters approved a bond measure to fund a two-hour-and-forty-minute Los Angeles to San Francisco high speed rail system. Today groundbreaking finally takes place in Fresno. In the intervening six years, lawsuits and political compromises have delayed the system and likely made the timetables promised to voters impossible to achieve. And even if all goes well, the system won’t fully connect Los Angeles to San Francisco until 2028, and that estimate seems wildly optimistic.

Yet today’s ceremony is still cause for celebration. Building a massive infrastructure project like this one across the state and its multiple political jurisdictions and interest groups is an almost impossible task. High speed rail, even if it’s less than perfect, will be an important contribution to the environmental and economic future of the state. With a growing population, California can only hope to move its residents efficiently via expanded rail, given the practical and economic limits on expanding our highways and airports. High speed rail also holds the promise of better integrating our existing transit systems and encouraging new ones, particularly in the Central Valley — a region that has missed out on the economic boom on the coast, in part due to its relative isolation from these economic centers (the UCLA/UC Berkeley Law report from 2013, A High Speed Foundation, details the potential benefits for the Valley from high speed rail).

The groundbreaking is finally occurring in part because state officials need to spend the federal dollars allocated to the project before 2017 or else lose them. But also because the High Speed Rail Authority appears to have found a legal way out of the many California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) lawsuits filed against it. The Authority recently appealed to the federal Surface Transportation Board (STB), essentially inviting that agency to rule that the CEQA lawsuits are preempted by federal law given the federal funds used for the first segment (such is the nature of CEQA that a state agency had to ask the federal government to preempt its home law). The STB came through last month, which will help clear out the seven CEQA cases pending against the Fresno to Bakersfield segment. On cue,the City of Bakersfield immediately settled with the Authority on its CEQA case.

But continued legal uncertainty will plague the project in the coming years. First, CEQA petitioners may appeal the STB decision to federal court. Second, the California Supreme Court will look at the issue of preemption raised by two conflicting appellate decisions (Friends of the Eel River and Town of Atherton). Finally, the courts will scrutinize the Authority’s final funding plan to ensure it complies with the strict terms of the 2008 ballot measure, such as the two-hour-and-forty-minute time requirement for the Los Angeles to San Francisco segment. Given that political compromises have greatly slowed the system’s cross-state travel, such as by diverting the Southern California route to Palmdale, serving hostile Central Valley cities in the eastern San Joaquin Valley directly rather than with spur lines, and using slower Caltrain tracks on the San Francisco Peninsula, meeting these timetables may very well be impossible.

But does it really matter anymore? Once the system starts, as it will today officially, it takes on a life of its own. Politically it becomes virtually impossible to stop. Financially, even though the state doesn’t have enough money now to build the whole system, future political generations will keep the torch lit and raise the necessary funds until they finish the job. And barring economic collapse or the plague, California’s transportation needs will only become more severe for a growing population, underscoring the need for alternatives like high speed rail.

So all aboard, ye California residents of 2028 (i.e. sometime in the late 2030s if we’re lucky). It hasn’t always been pretty, but it’s about time.