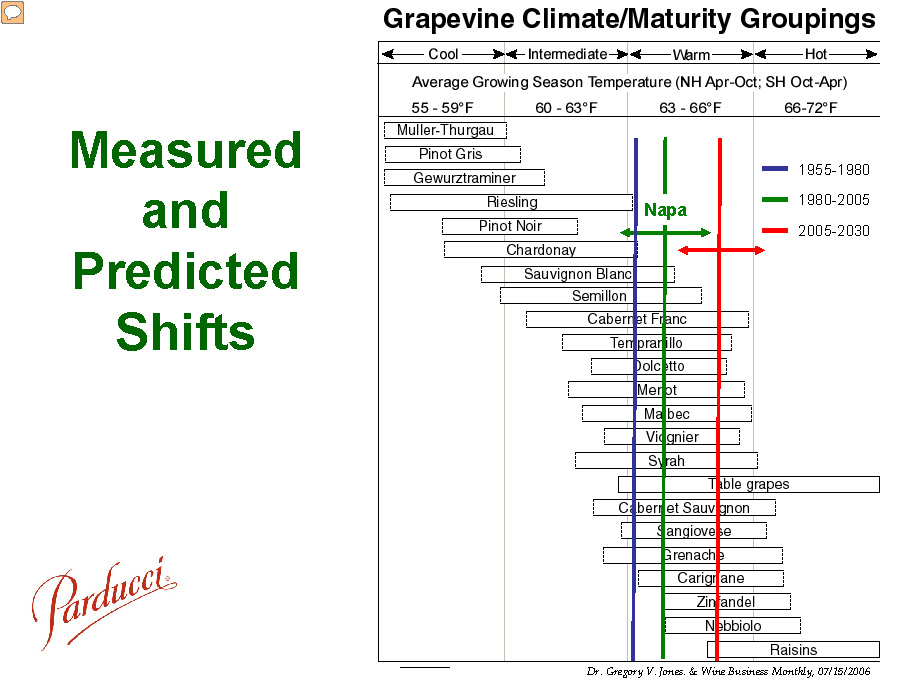

Back in 2009, when I first started working full time on climate change law and policy at Berkeley Law, I saw a presentation by a representative of a Napa winery at a California Assembly select committee hearing on climate change. Thomas A. Thornhill III, a partner at Parducci Wine Cellars/Paul Dolan Vineyards, showed the following slide:

As you can see from the chart, as the temperature warms (the red line), certain Napa grapes just won’t be able to survive anymore in the Valley, such as chardonay and sauvignon blanc (although it’s good news for raisin production in the Valley, for what that’s worth)

As you can see from the chart, as the temperature warms (the red line), certain Napa grapes just won’t be able to survive anymore in the Valley, such as chardonay and sauvignon blanc (although it’s good news for raisin production in the Valley, for what that’s worth)

I thought about that slide over Labor Day weekend this year, when a record-breaking heat wave with temperatures up to 117 degrees hit Napa. This new normal of extreme weather destroyed some of Napa and Sonoma’s premium cabernet grapes, as Bloomberg reported:

Vineyard consultant Steve Matthiasson, who also makes wines under his eponymous label, admitted, “The heat wave screwed us up.” While you need warmth to ripen cabernet, you don’t want too much, and this summer Napa had more than two dozen days with temperatures over 100 degrees. Before the grapes were completely ripe, an extreme heat wave on Labor Day weekend, which didn’t cool down at night, caused grape dehydration. As juice evaporated, some of the unripe grapes shriveled into raisins.

As a result, the wine grape crop is likely to be smaller than expected this year in California and beyond, down from 5 to 35 percent for some individual blocks of vines.

While this was a high-end casualty of climate change, it’s a demonstration of what will happen to the broader multi-billion agricultural industry across places like California as we veer into an increasingly hotter world.

And that’s nothing to toast.