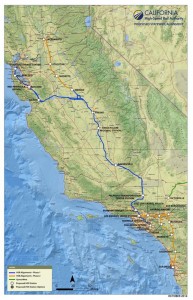

California’s high speed rail system has been moving at a low speed since voters approved a bond issue to launch it in 2008. That ballot measure authorized a bullet train from San Francisco to Los Angeles and eventually Anaheim, at speeds of 220 miles per hour and stops in Central Valley cities like Fresno and Bakersfield. The total trip time would be no more than 2 hours and 40 minutes between the two big cities, at fares less than airplane travel.

California’s high speed rail system has been moving at a low speed since voters approved a bond issue to launch it in 2008. That ballot measure authorized a bullet train from San Francisco to Los Angeles and eventually Anaheim, at speeds of 220 miles per hour and stops in Central Valley cities like Fresno and Bakersfield. The total trip time would be no more than 2 hours and 40 minutes between the two big cities, at fares less than airplane travel.

The rationale for the system is that it will provide a cheaper way to move a growing population around the state than expanding airports and highways. It will connect the relatively weak economies of the Central Valley with the prosperous coastal cities, providing an economic boost, all while enabling low-carbon transportation and promoting car-free lifestyles for communities connected to the system.

But since 2008, legal and political battles have slowed the system’s progress, as everyone from farmers in the Central Valley, wealthy homeowners in the San Francisco peninsula, and even equestrians in the hills above Burbank have fought to push the route away from their land. It’s local NIMBY politics on a statewide scale.

These legal and political challenges have in turn created funding headaches for the system. The original price tag of $40 billion ballooned to a projected $118 billion, before a revised business plan reduced it to an estimated $62 billion, as described in the 2016 business plan. Of that amount, the 2008 bond issues provides almost $10 billion, federal funds provide another $3.3 billion, and cap-and-trade funds may provide another few billion. System backers hope the rest come from private sources, but so far none have stepped up.

With strong support from the governor, the state was able to dedicate 25% of cap-and-trade auction proceeds to high speed rail construction. But the auction faces legal uncertainty going forward, due to a pending court case brought by the California Chamber of Commerce. An adverse verdict could mean that the money will halt either immediately or post 2020.

Meanwhile, the federal government has been unusually stingy with this infrastructure project. After Republicans took over Congress in the 2010 midterms, the federal dollars dried up, leaving the state to fund the project on its own. Only the 2009 stimulus provided some federal money for the train, but nowhere close to a match for the state contribution. By comparison, the federal government typically contributes 50% of the money for urban rail systems and between 90 and 100% for highways.

The funding picture has now affected the route design. The initial connections were going to be from the Central Valley to somewhere north of Los Angeles, hooking into the commuter Metrolink train to deliver passengers to Union Station in downtown Los Angeles. Now there’s not enough money to get the train through the Tehachapi mountains that separate Southern California from the Central Valley. So the initial connection will now go to San Jose from the Central Valley, with a link to the commuter Caltrain to get passengers to San Francisco. High speed rail bond money will then pay for upgrades to Caltrain and Metrolink, to prepare those systems for eventual high speed rail connections.

So with all the controversy and politics for this important project, I look forward to interviewing California High Speed Rail Authority chair Dan Richard tonight on City Visions, on NPR affiliate 91.7 FM KALW radio in San Francisco, from 7-8pm. For those out of the area, you can stream it or listen to the archived broadcast after the show here. I’ll ask Dan for more information on the funding, politics, and current construction status. And listeners are free to call in or email with questions. Hope you can tune in and ask your questions about the system’s future!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.