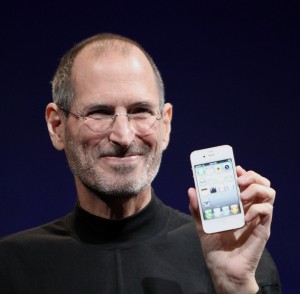

Steve Jobs died in 2011, but his life experience, as related by biographer Walter Isaacson, offers some important lessons for today’s transit and urban development practitioners. I just finished reading the biography and was struck — like many others — by what a notoriously awful person he was to those around him. Part of the challenge with someone as flawed as Jobs is accepting his ugly personal side along with the incredible positives he offered the world.

Those positives were not just the well-known products and companies he pioneered, from the personal computer revolution with Apple to Pixar to the iPod/iPad/iPhone phenomena. Rather, what I took away from the book was his philosophical approach to making great things, which inspired and enabled the products we all know. And that approach boiled down to making whatever you do excellent — like a fine piece of art.

Jobs was obsessed with detail and beauty. Even the Apple factory had to be elegant, clean, and organized, despite the lack of obvious economic benefit. He pushed his employees to create products that were beautiful like a Renaissance painting and simple and intuitive enough that a small child could grasp how to use them. This pride in aesthetics and desire to push his team to excellence helped make Apple products game-changers.

As U2 lead singer Bono argued of the iPod and its Apple creators:

These men have helped design the most beautiful art object in music culture since the electric guitar. That’s the ipod. The job of art is to chase ugliness away.

Significantly for transit and urban planners, Jobs emphasized a tight integration of typically disjointed company divisions in order to achieve this beauty and excellence. Apple’s designers, engineers, manufacturers, and product developers all worked in close collaboration. As Isaacson described:

At most other companies, engineering tends to drive design. The engineers set forth their specifications and requirements, and the designers come up with cases and shells that will accommodate them. For Jobs, the process tended to work the other other way. In the early days of Apple, Jobs had approved the design of the case of the original Macintosh, and the engineers had to make their board and components fit.

For transit in particular, this lesson points to the important need to build a product (rail transit) in close collaboration with the land use authorities in the jurisdiction through which the line travels. Too often, land use and transit decisions are uncoordinated. The transit agency focuses solely on getting the rail line built, and the rail planners and engineers devote themselves to logistics and street crossings and the like, instead of building toward a bigger picture of how the system fits into the surrounding environment. At most, a transit agency might seek to develop a few parcels it uses for construction staging near stations. But all the while, the local land use authority (the city or county) develops its own plans for the station area, in an often completely separate process.

The result at the human scale is that station entrances and access for pedestrians, bikers, bus riders, and drivers are not always inviting, practical, or safe. At the grander scale, the surrounding neighborhoods may lack the amenities, buildings, and destinations necessary to take full advantage of the system with higher ridership.

Perhaps the only long-term way to address the problem comprehensively is to consolidate transit and land use planning in one regional entity. Politically, that’s probably a nonstarter (although California’s SB 375 [2008] took a step in that direction), so the two processes need to be linked in other ways, such as requiring land use performance criteria from local governments before paying for rail lines to those communities. Transit agencies can also form working groups and joint planning committees with local land use authorities. This is good practice that doesn’t require policy changes.

For another lesson on land use, Jobs understood the value of public spaces to human happiness and creativity. He designed the Pixar studio in Emeryville, for example, so that the only bathrooms and amenities were located in a central atrium, forcing employees to have to walk there from all over the campus and therefore bump into each other. As Jobs explained in his biography:

There’s a temptation in our networked age to think that ideas can be developed by email and iChat. That’s crazy. Creativity comes from spontaneous meetings, from random discussions. You run into someone, you ask what they’re doing, you say ‘wow,’ and soon you’re cooking up all sorts of ideas.

While Jobs was focused in this case on economic productivity, we experience the social value of bumping into people in a public square, park, or other neighborhood meeting place. The happiest cultures I’ve seen all seem to have a proliferation of these spaces. People are often their most joyful when they can easily access such a gathering spot. Humans are social creatures, after all.

Jobs tried to take this concept to a higher level with his proposed “donut” or “spaceship” Apple headquarters (photo on the left). Of course, this suburban campus location flies in the face of the urban renaissance and trend toward putting offices in exciting city locations, like Twitter in San Francisco’s Mid-Market area. But leaving aside Jobs’ location choice, the design and purpose behind the building reinforce the value of walkable communities with vibrant public spaces.

Finally, Jobs offers two other thoughts that could be relevant for practitioners. One is not to use PowerPoint or Keynote slides (he would famously yell at anyone trying to show him slides, arguing that if you have to use them you probably don’t know what you’re talking about).

Second, and more positively, he described the need to love what you are doing in order to do it truly well.

The older I get, the more I see how much motivations matter. The Zune was crappy because the people at Microsoft don’t really love music or art the way we do. We won because we personally love music. We made the iPod for ourselves, and when you’re doing something for yourself, or your best friend or family, you’re not going to cheese out. If you don’t love something, you’re not going to go the extra mile, work the extra weekend, challenge the status quo as much.

While that thought applies to almost everyone, it’s a helpful reminder of what it takes to get the leadership and decision-making we need to create great urban spaces and the transit that connects them. Steve Jobs provided that lesson for us, and for that and many other insights, we can be grateful.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.