Boston and New York’s subways represent two of the most heavily utilized rail transit systems in the country. With transit ridership growing in the United States, much of that increase is led by these two cities. The two subways also happen to be the oldest in America.

So Doug Most’s new book on the history of the two systems, The Race Underground: Boston, New York, and the Incredible Rivalry That Built America’s First Subway, comes at a timely moment, especially as more people are focused on boosting transit nationwide to accommodate growing demand.

So Doug Most’s new book on the history of the two systems, The Race Underground: Boston, New York, and the Incredible Rivalry That Built America’s First Subway, comes at a timely moment, especially as more people are focused on boosting transit nationwide to accommodate growing demand.

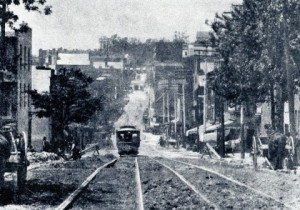

Most, a Boston Globe editor with New York roots, frames his story as a rivalry between the two cities at the end of the nineteenth century. He argues that they competed to see which one could build a subway first. Both cities were experiencing tremendous congestion from horse-drawn streetcars and later from electric surface streetcars.

But subways were not an easy sell. Although London opened the world’s first subway in 1863, the system used coal-fired steam engines that made the tunnels loud, polluted, and smelly — and therefore unappealing to other cities that might otherwise have copied London. Most also describes the typical Bostonian’s almost religious fear of going underground, where devils and bodies lay lurking.

But Most’s “rivalry” framing is a bit misleading. Neither city seemed particularly gung ho on developing a subway, outside of a few powerful interests and some traffic-weary residents. It took them decades to get final approval and funding (a sad parallel to many modern efforts to build rail, which can also take years and require political stars aligning). Boston didn’t even bother holding a groundbreaking ceremony or celebrating the opening, although Most never really explains why not.

Meanwhile, New Yorkers just shrugged when Boston opened their subway first. And while a number of other major world cities built subways during this time, no powerful, widespread political movements emerged in either city to fastrack construction. Mayors came and went in quick succession in both cities, with many of them uninterested in subways. Most’s “race” therefore seems to be slug-like meandering to get a subway started, decades after London opened its system and despite the awful street congestion.

The one powerful way the cities were linked, however, was through two brothers, Henry and William Whitney, who rose to prominence in each city and were both involved in transit. But even the brothers didn’t seem affected by sibling rivalry, so I wonder why Most framed the book that way. To me it would have been enough simply to frame the book as the story of the first two subways in America, rather than forcing a dramatic rivalry where none exists.

But aside from this framing, the book holds many interesting lessons for rail planning today. Of particular note is how quickly the two cities built their systems, once they finally got their political and financial acts together. Using pickaxes, shovels, and wheelbarrows, Boston built the first 1.8 miles through a densely populated commercial core in just two-and-a-half years, needing only a few years more to build the whole five-mile first segment. And the contractors came in under budget, too, spending $4.2 million out of the $5 million budgeted. Meanwhile, New York built an astounding 21 miles in 4.5 years, using tunnel shields, dynamite, and more pickaxes.

The fast rate of construction was primarily due to the “cut-and-cover” construction method (digging a trench in the road for the tracks and then covering it with a road surface roof) rather than the more difficult and dangerous tunneling process. Not a bad lesson for modern subway diggers that seem committed to using slow and expensive tunnel boring machines, like in San Francisco’s Chinatown project and LA’s subway to the sea. But the breakneck speed also came at the cost of human life. Most revels in detailing the numerous gruesome accidents and explosions, most of which seemed caused by incompetence and lack of safety regulations. The lesson for modern rail builders is that accidents definitely happen, and they invariably cost these projects public support.

The book also shows how NIMBYs (not-in-my-backyard) have been around for a long time. New York subway leaders saw their first serious subway attempt shot down by wealthy business merchants who did not want the disruption from the street digging. They found an ally in the court of appeals in New York (I wish Most had discussed the legal basis of the court opinion so we could see if the decision was based on sound legal reasoning or just politics). And as in Los Angeles almost a century later, subway planners in New York finally had to propose a gerrymandered route that avoided pockets of political opposition in order to get approval. In Boston, by contrast, the business NIMBYs along the first leg of the subway were not as politically powerful, similar to weak opposition movements in lower-income/high-renter communities. As a result, the Boston subway proceeded through their district over their objections.

Perhaps unintentionally, the book offers an interesting comparison to today’s efforts to electrify cars. From the beginning, people were impressed by the power and quality of electric motor technology (although ironically not Thomas Edison, who apparently was more interested in lighting). Just like electric vehicles today, electric streetcar motors were a disruptive event for the transit technology of the day: horses and cable and steam-powered trains. Most details the fascinating story of inventor and one-time Edison acolyte Frank Sprague, who struggled under Edison’s shadow and then on his own to perfect an electric streetcar system in Richmond. When Boston finally adopted the technology, riders marveled at the smoothness, acceleration, and cleanliness (no horse or steam smells) of the ride. Any driver of an electric vehicle today could probably relate.

A few nitpicky items: for readers like me who are not intimately familiar with either city, it would have improved the reading experience to see maps of the cities alongside description of the routes. And as a chronicler of the LA rail system, I hope Most will eventually correct his statement that LA is just now interested in building a “subway to the sea.” LA in fact already built a subway, from downtown to Hollywood and the San Fernando Valley. A new extension will likely go to Westwood in the late 2030s but probably not all the way to the ocean.

Overall, Most tells an engaging story of the two subways, using historical figures like characters in a drama and playing up the conflicts and accidents to maximum effect. If you’re a fan of the Boston or New York subways, or just like stories about huge infrastructure projects like rail, The Race Underground is an easy and worthwhile read.

3 thoughts on “The Slow Race to Build Boston and New York’s Subways — A Book Review”

-

Pingback: Downtown L.A. Businesses Successfully Sue to Study More Expensive Tunneling for New Rail Line | Ethan Elkind

-

Pingback: “Race Underground” PBS Documentary On Boston’s Subway History | Ethan Elkind

-

Pingback: Platooning Electric Buses Could Make Rail Transit Technology Obsolete | Ethan Elkind

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.