As I began researching the history of the Los Angeles Metro Rail system for my 2014 book Railtown, one particular aspect of the rail transit story shocked me. No, it wasn’t the petty political squabbles, short-sighted civic leadership, or selfish parochialism that slowed, weakened and sometimes stymied the development of a functional rail system in Los Angeles. It was the shocking price tag of building rail transit — particularly tunneling under busy city streets — and the absurd amount of time (decades in some cases) to dig tunnels that more than a century ago were done in a fraction of the time it takes today.

Like the rest of the United States, Los Angeles suffers from exorbitant costs and delays with tunneling. The 1.9 mile Regional Connector light rail tunnel under downtown, for example, will cost almost $1.7 billion and take at least 8 years to complete. Nationwide, as transit expert Alon Levy has documented, tunneling costs are out of whack even compared to other developed nations, with New York City’s $2.6 billion-per-mile Second Avenue subway as a particularly gruesome transit horror story.

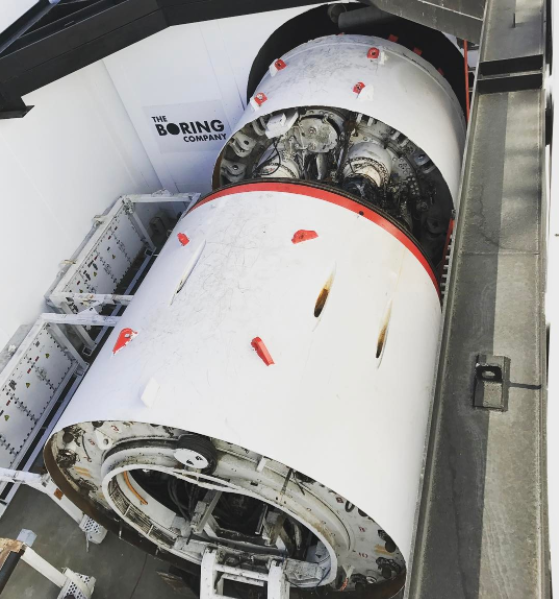

So I was intrigued this past December when I learned that Elon Musk’s Boring Company was unveiling a demonstration tunnel in Hawthorne, California, that could be built quickly and at a fraction of the cost. How cheap? 1.14-mile for just $10 million, with potential long-term improvements in speed of up to 15 times over the current rate.

Many urbanists sneered, deriding the tunnel as nothing more than a sewer pipe and mocking the idea of a “tunnel for Teslas” as simply recreating the failed surface roadway patterns of the present — or worse, catering to the wealthy by allowing them to avoid the congestion caused by the plebeians above.

Many of these same urbanists already resented Musk for his work with Tesla, a company which promotes a vehicle technology that they rightly identify as destroying our urban fabric, while he also (ironically) works to remove one of the arguments against cars by eliminating their tailpipe pollution.

But what if Musk and his rocket scientists from SpaceX really could bring down the cost and time of tunneling? Imagine the transit projects that could ensue. I’ll offer four, just here in California alone:

- A subway under Wilshire Boulevard in Los Angeles, the densest corridor west of the Mississippi, while Metro, the public agency currently trying to build one, is mired in a decade-long, multi-billion dollar slog.

- A subway connecting West L.A. with Sherman Oaks and the San Fernando Valley underneath the dreaded Sepulveda Pass and the freeway parking lot known as “The 405.”

- A second Bay crossing connecting Oakland and San Francisco to address congestion on BART and possibly allow one-seat train service from San Francisco to Sacramento.

- A tunnel connecting San Francisco to Los Angeles and San Diego, completing the dream of the flailing high speed rail project.

Those four projects alone would make any California urbanist happy. Yet how seriously can we take the Boring Company’s claims regarding decreased tunneling costs and time?

I took a tour of the test tunnel in Hawthorne last month to try to gain more clarity on how the company is reducing tunnel costs. Three things stood out:

- The Dirt. Believe it or not, what to do with the dirt that comes out of tunnels is a big limiting factor. I heard this first-hand from the tunneling experts working on the Regional Connector project under downtown Los Angeles. Yet the Boring Company may have found something simple and innovative to do with that dirt: turn them into functional bricks. To prove their point, they built a Monty Python-style tower out of the bricks on site. If the bricks can be given away for free, it will greatly reduce costs. If they can sell the bricks for use in things like sound walls, they say they could actually make money on the tunnel (see the picture above and video below of the dirt brick-making process).

- Private funding incentives. The Boring Company is envisioning a privately funded network of tunnels throughout California and beyond. They are not necessarily contemplating bidding on large public sector contracts. As a result, the company appears to have incentives to cut costs in ways that some of the few big tunneling companies competing for select large public contracts may not. As an example, the company can save costs simply in terms of where they manufacture the tunnel’s concrete segments relative to the tunnel, a cost-saving step that they say the big tunneling contractors aren’t financially motivated to take.

- Lots of little things. There appears to be no one single leap forward with the Boring Company machine. But instead, the company’s leaders say they’ve managed a series of smaller innovations that combined together could help reduce the costs dramatically. Perhaps most significantly, the tunnel bore has a smaller diameter than many rail tunnels because they don’t need the wiring and infrastructure that a train needs, but it’s still large enough to fit a vehicle with the carrying capacity of a subway train. Their vision is to run battery-powered, autonomous vehicle platforms in the tunnels, rather than hard wire expensive rail cars. It’s a vision of where technology is heading that could eventually lead to existing rail transit being converted to autonomous, battery-powered, platooning shuttles, which could carry the same passengers as rail but for a fraction of the capital and operating costs.

In any event, we’ll soon see if these company claims are accurate, as the Boring Company appears ready to work on a tunnel under the Las Vegas convention center soon.

And while urbanists fret about the potential for expanded subterranean capacity for solo drivers, there’s no reason that the technology would only be employed for that use and couldn’t scale to the level of current public rail transit. The company sees Model X battery-powered platforms seating between 16 and 32 passengers traveling up to 165 miles per hour through LED-lit tunnels. And with five boring machines in action, they think they could reach San Francisco in just a year. That vision — though of private and not public transit — would only bolster urbanist goals of car-free living in more dense, transit-oriented communities.

A big limiting factor though, beyond the technology, may be permitting. Environmental review under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) may slow this deployment. Under the law, permitting agencies will have to study and mitigate environmental impacts ranging from paleontology to induced land use changes and traffic at the surface entry points to the tunnel. We’ll see how that process plays out, if the Boring Company starts moving forward on a project in California.

But if Musk and his crew have actually solved the technology and cost problem of tunneling, they will have given transit backers throughout the United States and beyond a big reason to celebrate. Because a revolution in tunneling is a pipe dream worth pursuing in our increasingly urban world.