Texas, of all places, appears to be beating California in the high speed rail game. As I’ve written before, the proposed line between Dallas and Houston has all the right attributes for success, and it is on track (ahem) with private financing to be up and running by the early 2020s.

Meanwhile, California’s progress is much slower (to be completed sometime in the 2030s at best), while the funding picture grows ever murkier. The financing has recently been undermined by poor cap-and-trade auction proceeds that Governor Brown is using to backstop the lack of available federal and private dollars.

But Texas’ early success could benefit California in key ways. First, it could improve the funding and economics of California’s system. A Texas system could encourage high speed rail manufacturing in the United States. This local production would help California obtain domestically sourced (and possibly cheaper) parts and supplies, which would allow the state to comply more fully with federal funding requirements and therefore secure more such funding.

Texas’ success could also improve the politics for California. Having high speed rail in red state Texas could change congressional attitudes and achieve more bipartisan support for high speed rail in general. That dynamic could lead to more federal dollars for the system, which have been stalled since Republicans took over the House of Representatives.

Finally, Texas’ experience could potentially inspire some improvements to California’s system design. Because California’s is primarily a government-funded system, the route has to satisfy various political constituencies. But with a privately funded system, the Texas train is all about the economics, in terms of speed and service between the most populated areas. As E&E reports (paywall):

And rather than build more than a dozen stations, which would slow California’s line, Texas Central is planning on just three stations: Houston, a central stop roughly halfway between College Station and Huntsville, and Dallas.

Though historically, governments built these systems, Kelly says his company’s private financing model actually gives it the advantage.

“It’s really hard, especially on those long routes, to have fares that are high enough but don’t price everybody out of the market and still pay for the service,” he said. “But even in Amtrak, you find some profitable routes, like the Northeast Corridor.”

Given California’s challenges in attracting federal and private funding to high speed rail, the Texas example may provide important lessons that decision-makers can incorporate. Most prominently, it may involve subtracting some stations in the middle of the route.

At some point, California leaders may need a retrenchment of the system plans to address the financing issue, barring any infusion of federal or private dollars. Who would have thought that Texas may end up as a role model for California’s high speed rail?

The Dallas to Houston route looks like it may be on-line faster than California’s Madera to somewhere-near-Bakersfield segment, per Jeff Turrentine at NRDC:

The Dallas to Houston route looks like it may be on-line faster than California’s Madera to somewhere-near-Bakersfield segment, per Jeff Turrentine at NRDC:

Now, nearly 50 years after its founding, Southwest may soon face unexpected competition for its always-booked Dallas-to-Houston service. And in a telling bit of irony, this new rival has come in the form of a railway company, of all things.

After several years spent getting its legal, financial, and procedural ducks in a row, the company known as Texas Central is moving ever closer to realizing its goal of linking two of Texas’s biggest cities via high-speed bullet train. Though a few right-of-way issues still need to be cleared up, Texas Central seems on track (I know, I know; I’m sorry) to break ground on its 240-mile-long rail system in early 2017, with service scheduled to begin within the next five years. Then the nearly 50,000 Texans whom the company has identified as Dallas-to-Houston “supercommuters”—i.e., those who drive or fly between the two cities more than once a week—will have a highly attractive third option: climbing aboard sleek, swift, tricked-out trains that depart every half-hour and reach their center-city destinations in under 90 minutes.

So what’s the secret sauce that enables Texas to get moving while California plods along, aiming to finish sometime in the 2030s? Well, I’m sure it’s cheaper and easier to build in a place like Texas, with fewer environmental restrictions and a flat terrain (no Tehachapis to deal with).

But perhaps more importantly, the rail system would connect two major cities on a straight line, covering a distance that’s a bit too far to drive and pretty close to fly. In other words, it’s the sweet spot for high speed rail. And with that fast connection, private money is flowing.

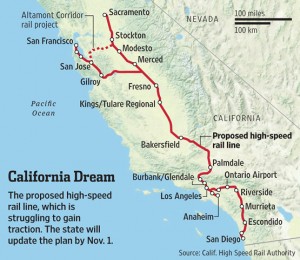

Contrast that approach with California, which is zigzagging its train from Los Angeles to San Francisco in order to satisfy various political constituencies. The result is less private sector appetite to invest and a rail connection that requires significant public support and a long time horizon to build.

I’m certainly rooting for California to build high speed rail, but red state Texas may just beat California to the punch.