When California state agencies and other local leaders build or approve projects that increase overall driving miles, state law requires them to mitigate those impacts. A new report from CLEE describes how these agencies can reduce vehicle miles traveled (VMT) by investing in offsite options like bike lanes, bus-only lanes, transit passes, and other measures that can effectively and efficiently reduce a corresponding amount of VMT.

Under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), government agencies and developers are required to mitigate (where feasible) the significant environmental impacts of new projects subject to discretionary approval, including impacts to transportation.

Senate Bill 743, originally enacted in 2013, called for a new transportation impact measure that promotes greenhouse gas (GHG) emission reduction and multimodal transportation. In 2018 state leaders updated the CEQA guidelines to recommend VMT as the preferred impact measurement. VMT focuses on total vehicle trip-miles generated by a new project regardless of where they occur or how much traffic they cause.

Mitigating VMT impacts of new projects has the potential to shift California’s development patterns in a more sustainable, transit-oriented direction. It also creates the opportunity—and potentially the need—to conduct mitigation at locations other than the development site when onsite mitigation is not possible or practical. Such offsite mitigation can address the regional and statewide nature of VMT impacts in the most efficient and cost-effective locations, particularly when mitigation might prove difficult at the site of a suburban or exurban development.

If properly conducted, offsite mitigation could maximize flexible and locally appropriate transit, active transportation, and density investments. But to carry it out, state and local government leaders will need new frameworks to track mitigation obligations, plan investments, and facilitate transactions. CLEE and others have previously proposed “bank” and “exchange” programs to manage these capacities.

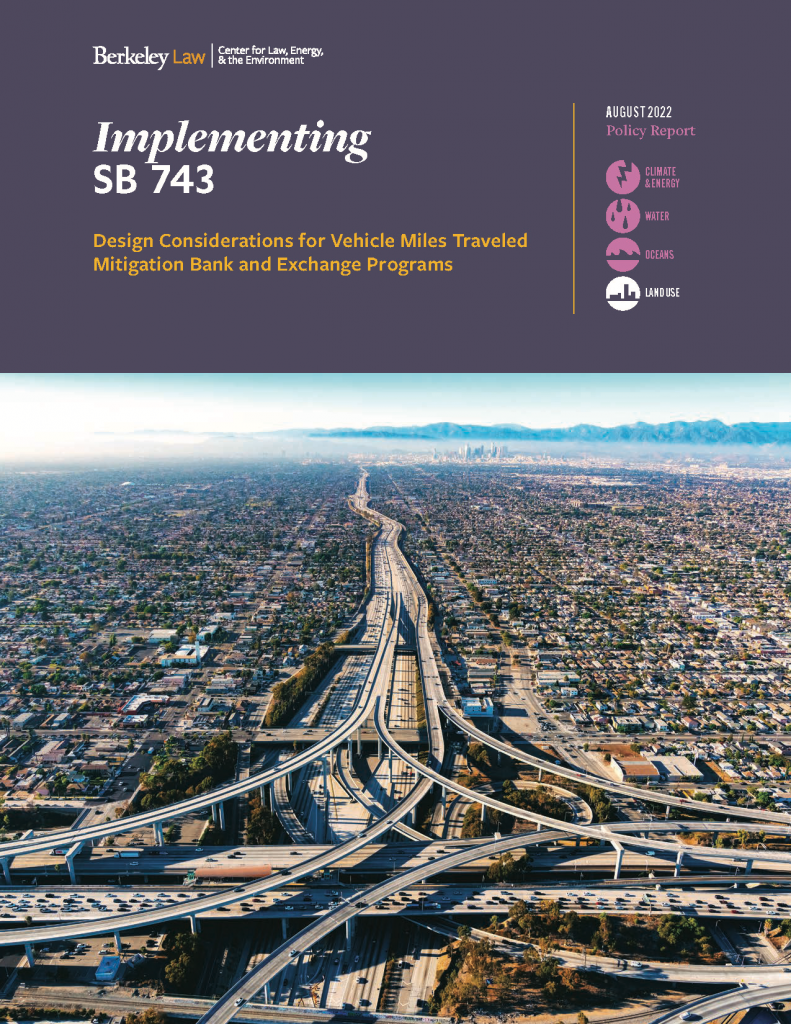

CLEE’s new report, Implementing SB 743: Design Considerations for Vehicle Miles Traveled Bank and Exchange Programs advances these proposals with a set of strategies for state agencies like Caltrans (the state agency most likely to be responsible for VMT-inducing projects) and local governments to develop bank and exchange programs that build on their existing environmental mitigation efforts. In addition to analyzing the legal and programmatic setting for VMT mitigation banks and exchanges, the report offers a set of recommendations for policymakers including:

- A state-level program for state agencies to manage mitigation and select locally appropriate investments, likely based on collaboration between Caltrans and other state transportation and land use agencies

- Regional-level programs for local and regional agencies to manage mitigation flexibly and efficiently within appropriate geographic limitations—likely managed by Metropolitan Planning Organizations or Regional Transportation Planning Agencies, but potentially run by large cities or counties in some cases

- Frameworks for analyzing the “additionality” of VMT mitigation investments to ensure that bank and exchange program funds support VMT reductions beyond those that would have occurred anyway

- Strategies for defining equity in the context of VMT mitigation and integrating equity into the decision-making of a bank or exchange program

Cities and counties around the state, from San José to San Diego, are in the process of developing their own approaches that could become, or could integrate into, VMT banks and exchanges. Caltrans and local government leaders will require significant time and resources to develop programs that fit the nature of the VMT-inducing projects they oversee and the needs and priorities of the areas they represent—and many questions remain, from prioritizing different mitigation investments to ensuring those investments are made in an equitable fashion. The strategies outlined in the report should help inform these decisions and advance the VMT reduction efforts initiated by the legislature nearly a decade ago.

This post was originally co-authored by Ted Lamm and Katie Segal on Legal Planet.

California ushered in a whole new way of evaluating the impacts of new projects on our transportation systems when the legislature passed SB 743 (Steinberg, 2013). The implementing guidelines are finally complete, and lead agencies will now be responsible for switching from an “auto delay” metric under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) to one that measures the impacts on overall driving miles (VMT).

To discuss the implementation process, Berkeley Law’s Center for Law, Energy and the Environment (CLEE) is co-hosting a conference with Portland State University this Friday, March 1st, in Downtown Los Angeles from 8:45 to 6pm. In-person tickets are now sold out, but you can register to view it on line or watch as a webinar afterwards. The agenda is here.

Speakers include Sacramento mayor and SB 743 author Darrell Steinberg (via video), officials from the Governor’s Office of Planning and Research, local leaders implementing innovative VMT mitigation plans, and other experts.

We’ll also discuss our recent CLEE report “Implementing SB 743” on the legal options for creating VMT mitigation “banks” or exchanges. Hope to see you there or that you can tune in live!

It took five years, but California has finally ditched an outdated and counter-productive metric for evaluating transportation impacts under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). With the guidelines finalized on December 28th, a mere half-decade since the passage of SB 743 (Steinberg) in 2013, the state will ditch “auto delay” as a measure of project impacts and instead measure overall driving miles (VMT). You can see the new guidelines Section 15064.3.

It’s a big deal. Now new projects like bike lanes, offices, and housing will be presumed exempt from any transportation analysis whatsoever under CEQA if they are within 1/2 mile of major transit or decrease driving miles over baseline conditions. That means significantly reduced litigation risk and processing time for these badly needed infill projects.

Sprawl projects, meanwhile, will need to account for and mitigate their impacts from dumping more cars on the road for longer driving distances. Berkeley Law’s Center for Law, Energy and the Environment (CLEE) explored one such mitigation option in the form of a VMT “mitigation bank” or exchange in the recent report Implementing SB 743, where developers could pay into a fund to reduce VMT, such as for new transit or bike lane projects.

Sprawl projects, meanwhile, will need to account for and mitigate their impacts from dumping more cars on the road for longer driving distances. Berkeley Law’s Center for Law, Energy and the Environment (CLEE) explored one such mitigation option in the form of a VMT “mitigation bank” or exchange in the recent report Implementing SB 743, where developers could pay into a fund to reduce VMT, such as for new transit or bike lane projects.

The one caveat is that due to political pressure, new roadway expansions are exempt from this requirement under the guidelines. It’s unfortunate, but those roadway projects will still need to undertake VMT analysis anyway for climate and air quality impacts, so perhaps they are not as exempt as their backers hoped.

You can learn more about these changes and what they mean going forward at a March 1st conference that CLEE is co-organizing in Los Angeles with the Urban Sustainability Accelerator at Portland State University. Shifting from Maintaining LOS to Reducing VMT: Case Studies of Analysis and Mitigation under CEQA Guidelines Implementing SB 743 will be a professional educational program for land use, transportation and environmental planners and attorneys in public, private and nonprofit practice, presented by expert practitioners.

- When: Friday March 1, 2019

- Where: Offices of the Southern California Association of Governments, Los Angeles

Topics to be discussed include:

- VMT impact analysis (methodology; appropriate tools and models, determining impact area)

- VMT significance thresholds (project effects, cumulative effects)

- VMT significance thresholds (project, cumulative)

- VMT mitigation strategies (project level, programmatic, VMT banks and transaction exchanges, legal and administrative framework)

Space is limited to 70 people to attend in person; registrants can view the program online streaming concurrently or subsequent to the program.

Registration Fees:

- Free Staff of state, regional and local governments sponsoring the SB 743 implementation assistance project and of their member governments (use link below for information about affiliations qualifying for free registration)

- $30 General registration, not seeking professional education credits

- $90 Planners seeking 6 AICP credits* ($15/credit)

- $210 Attorneys seeking 6 MCLE credits* ($35/credit)

*The organizer has accreditation for six hours of California Mandatory Continuing Legal Education (MCLE) credits and is seeking accreditation for six hours of AICP credits.

You can learn more about this conference here and can proceed directly to the online preregistration form here.

This has been a relatively eventful year in California land use, given the state’s severe housing shortage, and I’ll be speaking about it this morning at the 14th Annual “CEQA Year In Review” Conference in San Francisco. The morning panel will cover “Streamlining CEQA for Housing Approvals.”

This has been a relatively eventful year in California land use, given the state’s severe housing shortage, and I’ll be speaking about it this morning at the 14th Annual “CEQA Year In Review” Conference in San Francisco. The morning panel will cover “Streamlining CEQA for Housing Approvals.”

I’ll cover the state’s relatively lackluster effort to date to streamline environmental review for infill housing projects, which has had limited success in allowing environmentally beneficial infill projects to avoid costly and time-consuming environmental review. And as my colleague Eric Biber has found, much of the problem traces to local government decisions to make approvals discretionary for larger projects, which automatically triggers the environmental review process.

I’ll also discuss potentially promising state-level effort to require upzoning around major transit, such as this past year’s AB 2923 to upzone BART-owned parcels as well as this coming session’s SB 50 debate. But even if the state can accomplish mandatory upzoning, locals will still try to stop new projects by instituting lengthy approval processes with multiple veto points. So the next phase in the battle to address the housing shortage will probably be to limit local permitting discretion over projects near major transit.

I look forward to the discussion and hope to see you at the conference today!

Under Senate Bill 743 (Steinberg, 2013), California will soon require developers of new projects, like apartment buildings, offices, and roads, to analyze and mitigate the amount of additional driving miles their projects generate. To facilitate compliance with SB 743, some local and regional leaders are considering creating “banks” or “exchanges” to allow developers to fund off-site projects that reduce vehicle miles traveled (VMT), such as new bike lanes, transit, and busways.

Under Senate Bill 743 (Steinberg, 2013), California will soon require developers of new projects, like apartment buildings, offices, and roads, to analyze and mitigate the amount of additional driving miles their projects generate. To facilitate compliance with SB 743, some local and regional leaders are considering creating “banks” or “exchanges” to allow developers to fund off-site projects that reduce vehicle miles traveled (VMT), such as new bike lanes, transit, and busways.

CLEE’s recent report, Implementing SB 743, provides a comprehensive review of key legal and policy considerations for local and regional agencies tasked with crafting these innovative VMT mitigation mechanisms, including:

- Legal requirements under CEQA and Constitutional case law;

- Criteria for mitigation project selection and prioritization;

- Methods to verify VMT mitigation and “additionality”; and

- Measures to ensure equitable distribution of projects.

CLEE will hold a free webinar tomorrow, Tuesday, October 30th from 10-11am to discuss the report findings and answer questions about SB 743 and VMT mitigation strategies. Speakers will include:

- Chris Ganson, Governor’s Office of Planning & Research

- Jeannie Lee, Governor’s Office of Planning & Research

My colleague Ted Lamm and I will also join. You can register for the webinar (hosted on Zoom) and download Implementing SB 743.

California law now requires developers of new projects, like apartment buildings, offices, and roads, to reduce the amount of overall driving miles the projects generate. Senate Bill 743 (Steinberg, 2013) authorized this change in the method of analyzing transportation impacts under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), from auto delay to vehicle miles traveled (VMT).

California law now requires developers of new projects, like apartment buildings, offices, and roads, to reduce the amount of overall driving miles the projects generate. Senate Bill 743 (Steinberg, 2013) authorized this change in the method of analyzing transportation impacts under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), from auto delay to vehicle miles traveled (VMT).

In response to SB 743, some state and local leaders are seeking to create special “banks” or “exchanges” to allow developers to fund off-site projects that reduce VMT, such as new bike lanes, transit, and busways. These options could be useful when the developers lack sufficient on-site mitigation options.

A new report from Berkeley Law’s Center for Law, Energy and the Environment (CLEE), Implementing SB 743, provides a comprehensive review of key legal and policy considerations for local and regional agencies tasked with crafting these innovative mechanisms, including:

- Legal requirements under CEQA and Constitutional case law;

- Criteria for mitigation project selection and prioritization;

- Methods to verify VMT mitigation and “additionality”; and

- Measures to ensure equitable distribution of projects.

The report recommends that decision makers launching new VMT banks and exchanges consider including:

- Measures to verify the legitimacy of claimed VMT reductions, as well as their “additionality”;

- Prioritization of individual mitigation projects, in order to ensure that reductions are achieved as quickly and efficiently;

- Rigorous backstops to ensure that disadvantaged communities are not negatively impacted by—and ideally can benefit from—the ability of developers to move mitigation off-site; and

- Demonstration of both a reasonable substantive relationship and financial proportionality between the proposed development and the fee or condition placed on it.

Ultimately, SB 743 implementation will require a range of approaches from jurisdictions of varying sizes, densities, and development patterns throughout California. Local, regional, or even statewide mechanisms may evolve as mitigation programs mature and potential efficiencies are identified. Implementing SB 743 offers a guidebook to agencies and developers navigating the law’s new approach.

For more information, join CLEE’s webinar on Tuesday, October 30th from 10-11am with Governor’s Office of Planning and Research senior planner Chris Ganson and report co-author Ted Lamm and me. You can register for the free webinar today.

For those interested in the latest legislative updates and debates on housing and land use in California, I’ll be speaking this weekend at the Planning and Conservation League’s annual “Environmental Assembly” conference in Sacramento. I’ll be on an afternoon panel with:

- Kip Lipper, Chief Policy Adviser on Energy and Environment, Office of Senate President Pro Tem Kevin de León

- Winter King, Shute Mihaly & Weinberger, LLP

- Doug Carstens, Chatten-Brown & Carstens, LLP

We’ll discuss recent updates to the California Environmental Quality Act under SB 743, recent legislation like SB 35, as well as pending legislation like SB 827.

More details here:

What: Planning and Conservation League’s 2018 California Environmental Assembly

When: Saturday, February 24, 2018, registration and breakfast starts at 7:30 am

Where: McGeorge School 3200 5th Ave, Sacramento, CA 95817

It’s taken a long time, but California finally is ready to make a significant change to speed environmental review for new transit and infill projects. The Governor’s Office of Planning & Research (OPR) announced on Monday that a compromise has been reached to implement SB 743 (Steinberg, 2013), a law that made major amendments to the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), the state’s law governing environmental review of new projects.

Back in 2013, the legislature passed SB 743 to change how infill projects undergo environmental review. Under the traditional regime, project proponents had to measure transportation impacts by how much the project slowed car traffic in the immediate area. The perverse result was mitigation measures to privilege automobile traffic, like street widening or stoplights for rail transit in urban environments or new roadways over bike lanes in sprawl areas.

But the true transportation impacts are on overall regional driving miles. An urban infill project may create more traffic locally but can greatly reduce regional traffic overall by locating people within walking or biking distance of jobs and services. Meanwhile, a sprawl project may have no immediate traffic impacts, but it typically dumps a huge amount of cars on regional highways, leading to more traffic and air pollution. As a result, the switch from the “level of service” (auto delay) metric to “vehicle miles traveled (VMT)” made the most sense. Most infill projects are exempted entirely under this metric, while sprawl projects would have to mitigate their impacts on regional traffic.

But OPR’s implementing guidelines with this change were held up by highway interests and their government allies, who don’t want the law to apply to highways. You can probably see why: highways are designed to do one thing only — induce more driving. And that would score poorly under this change to CEQA.

State leaders finally reached a compromise this month: the new guidelines could apply statewide to all projects (something only suggested by the statute), but new highway projects can still use the old “level of service” metric, at the discretion of the lead agency (see the PDF of the guidelines for more details at p. 77).

It’s an unfortunate but probably necessary concession to powerful highway interests. Even though freeways have consistently failed to live up to their promise of fast travel at all times, and instead brought more traffic, sprawl and air pollution to the state, many California leaders are still wedded to this infrastructure investment.

My hope is that the compromise won’t actually mean that much new highway expansion in the state. First, California isn’t planning to build a lot of new highways, outside of the ill-advised “high desert corridor” project in northern Los Angeles County. Second, even for new highway projects, CEQA’s required air quality review may necessitate an analysis of (and mitigation for) increased driving miles.

Either way, smart growth advocates can at least celebrate the good news that CEQA will finally be in harmony with the state’s other climate goals on infill development, transit, and other active transportation modes.

The guidelines though still need to be finalized by the state’s Natural Resources Agency, which will take additional months. I’ll stay tuned in case anything changes with the proposal during this time.

Traffic studies are a great way to kill an infill project. Under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), they’re required for most big projects. And when you’re building in an already-developed area, you’re likely going to make traffic worse in the immediate surroundings. So most infill projects flunk that test, while they ironically decrease traffic region-wide.

Traffic studies are a great way to kill an infill project. Under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), they’re required for most big projects. And when you’re building in an already-developed area, you’re likely going to make traffic worse in the immediate surroundings. So most infill projects flunk that test, while they ironically decrease traffic region-wide.

That’s why I’ve been a strong supporter of the effort to implement SB 743 by the Governor’s Office of Planning and Research (OPR), which recently released new draft implementing guidelines. Essentially, SB 743 required OPR to transition California away from the traffic study metric of “level of service” (or auto delay) and toward a “vehicles miles traveled” (VMT) approach.

Under VMT, most infill projects generate so few driving miles per capita that they’d be exempt from further study. Sprawl projects would meanwhile come under greater scrutiny for loading up our highways with long-distance commuters, even if they don’t delay much traffic in the immediate vicinity.

While sprawl builders and their allies have protested the change, we now see growing opposition in infill areas from local opponents of density. San Francisco has been ahead of the state in making this switch, and Zelda Smith of the 48 Hills blog is up in arms:

Regional congestion is an abstraction that has never been and never will be experienced by anyone. Local congestion is something that everyone has experienced, and that everyone will experience more intensely as a result of SB 743. The staff report to the Planning Commission concedes as much, averring that “it is often not feasible in developed urban areas like San Francisco to improve LOS.” So we just make local traffic congestion worse by disregarding the local traffic impacts of infill development?

I’m actually sympathetic to this argument to some degree. Local congestion is a problem for the people who live there, and even if most new residents of an infill project walk or take transit, the project will create a local burden.

But that doesn’t mean we need to toss out the VMT metric and keep the dysfunctional status quo. Rather, local governments are still free to mitigate local traffic impacts through their codes, rather than relying on CEQA. And a great way to mitigate the traffic impacts of a local infill project would be to increase bike and pedestrian infrastructure and require transit passes for new residents, rather than downscaling the project or widening local road lanes.

If you oppose density just because you don’t want change, those mitigations won’t satisfy you. But if you’re genuinely concerned about increased traffic in your neighborhood, it would be a better solution than forcing change through CEQA and litigation threats.

Yesterday I had a chance to talk to Damien Newton at Streetsblog California for his podcast #DamienTalks about the changes underway to the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) on transportation analysis. Damien is particularly interested in the California Infill Builders Federation opposition to the change from auto-delay to vehicle miles traveled, so we discussed the politics around their legislation to halt the change:

Today #DamienTalks with Ethan Elkind, about the efforts to reform how the state measures transportation impacts of a proposed project. Currently, the state measures how a project impacts car travel time, but a change to state law will turn that rule on its head so that we’re encouraging projects that don’t produce more car trips instead of just mitigating the ones that do.

Not surprisingly, there is pushback. Surprisingly, it’s coming from a group that should gain from the change from “LOS” to “VMT.”

You can access the podcast here or via Damien’s site linked above.