This has been a relatively eventful year in California land use, given the state’s severe housing shortage, and I’ll be speaking about it this morning at the 14th Annual “CEQA Year In Review” Conference in San Francisco. The morning panel will cover “Streamlining CEQA for Housing Approvals.”

This has been a relatively eventful year in California land use, given the state’s severe housing shortage, and I’ll be speaking about it this morning at the 14th Annual “CEQA Year In Review” Conference in San Francisco. The morning panel will cover “Streamlining CEQA for Housing Approvals.”

I’ll cover the state’s relatively lackluster effort to date to streamline environmental review for infill housing projects, which has had limited success in allowing environmentally beneficial infill projects to avoid costly and time-consuming environmental review. And as my colleague Eric Biber has found, much of the problem traces to local government decisions to make approvals discretionary for larger projects, which automatically triggers the environmental review process.

I’ll also discuss potentially promising state-level effort to require upzoning around major transit, such as this past year’s AB 2923 to upzone BART-owned parcels as well as this coming session’s SB 50 debate. But even if the state can accomplish mandatory upzoning, locals will still try to stop new projects by instituting lengthy approval processes with multiple veto points. So the next phase in the battle to address the housing shortage will probably be to limit local permitting discretion over projects near major transit.

I look forward to the discussion and hope to see you at the conference today!

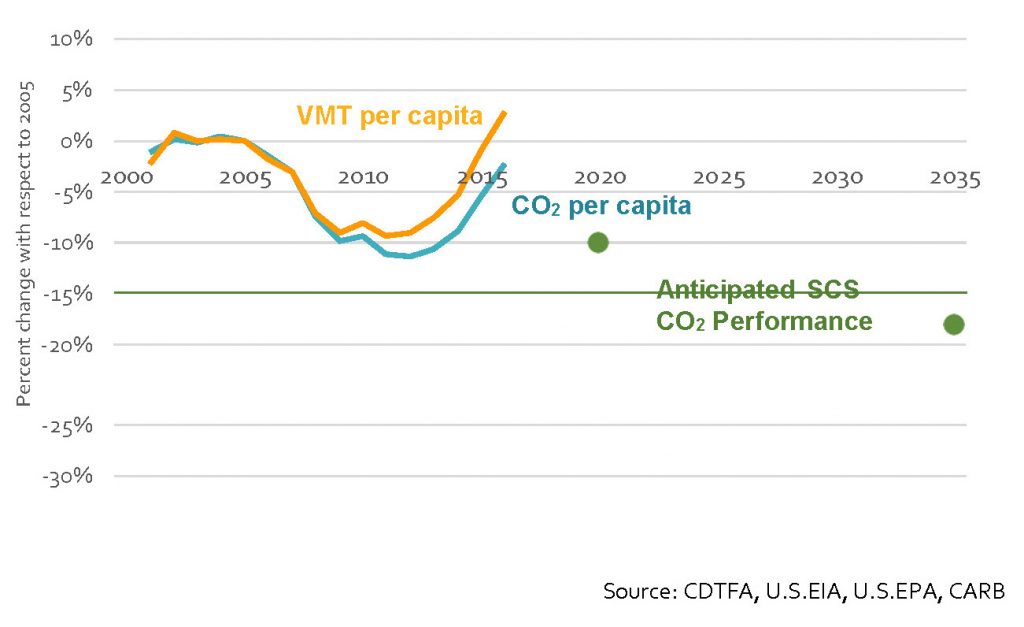

California’s major urban regions are falling behind in getting people out of their solo drives in favor of walking, biking, transit and carpooling, according to a major report last month from the California Air Resources Board. In short, the state will not meet its 2030 climate goals without more progress on reducing vehicle miles traveled (VMT):

This result comes despite the decade-old passage of SB 375 (Steinberg, 2008), which promised to reorient land use and transportation around reduced driving. The lone exception appears to be the San Francisco Bay Area, which has seen steadily increasing transit ridership and decreasing solo driving to work as a percentage, according to the report.

This result comes despite the decade-old passage of SB 375 (Steinberg, 2008), which promised to reorient land use and transportation around reduced driving. The lone exception appears to be the San Francisco Bay Area, which has seen steadily increasing transit ridership and decreasing solo driving to work as a percentage, according to the report.

What are the stakes if California can’t start solving this problem in the next decade? A U.N. report on climate change recently concluded that limiting global warming to 1.5 C would “require more policies that get people out of their cars — into ride-sharing and public transportation, if not bikes and scooters — even as cars switch from fossil fuels to electrics.” In order to keep the world on track to stay within 1.5 Celsius, the report stated that emission reductions would have to “come predominantly from the transport and industry sectors” and that countries couldn’t just rely on zero-emission vehicles alone.

Yet as the report shows, California’s current land use policies are not helping with this goal. We need to discourage development in car-dependent areas while promoting growth close to jobs, as SB 50 would allow. And at the same time, we need to invest in better transit service. Otherwise, California and jurisdictions like it around the world will fail to avert the coming climate catastrophe.

Last year, State Senator Scott Wiener (D-San Francisco) went right to the heart of California’s massive housing shortage in its job-rich centers with SB 827, which would have limited local restrictions on housing near transit. The bill went down in committee, a victim of election year politics and diverse opposition from wealthy homeowners, tenants rights advocates, and even a few misguided environmental organizations.

Last year, State Senator Scott Wiener (D-San Francisco) went right to the heart of California’s massive housing shortage in its job-rich centers with SB 827, which would have limited local restrictions on housing near transit. The bill went down in committee, a victim of election year politics and diverse opposition from wealthy homeowners, tenants rights advocates, and even a few misguided environmental organizations.

Now Senator Wiener is back at it with Senate Bill 50, which retains most of the heart of SB 827 but with a few changes to address the anti-displacement concerns over low-income tenants who might be evicted with new infill development.

Here is a summary of the provisions:

- Easing local zoning restrictions on new housing: SB 50 would eliminate local restrictions on density and on-site parking requirements greater than 0.5 spaces per unit for residential projects within one-half mile of “major transit” (rail and ferry) stops, as well as projects within one-quarter mile of major bus stops. It would also reduce the minimum floor-area ratio (percentage of the parcel that is developed) and height restrictions to nothing less than 45 feet within one-half mile and 55 feet within one-quarter mile of rail and ferry stops. Notably, these height limits are lower than the original version of SB 827 but basically consistent with the amended version before it was killed in committee.

- Geographic applicability: SB 50 is both more and less restrictive in its applicable geography than SB 827. The one-half mile radius is consistent, but now it no longer applies to all half-mile areas around major bus stops. Instead, the bill only applies its basic provisions to one-quarter mile of high-quality bus stops (defined as having peak commute headways of 15 minutes or less). It’s more expansive though in that it now applies to communities that are determined to be “job rich” and affluent, but not necessarily close to transit. The Governor’s Office of Planning and Research and Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD) are charged with making the determination of what constitutes such a community, based on loose factors like proximity to jobs, high area median income relative to the relevant region, and high-quality public schools. And notably, the bill now applies to housing not just on residentially zoned land but land that may also be zoned commercial or mixed-use but allows for housing, too. But off the table (more below) are “sensitive communities” at risk of gentrification and displacement.

- Tenant protections & affordability requirements: the final amended version of SB 827 contained some strong anti-displacement provisions, and this bill picks up on those changes and expands them. For example, the bill does not apply to any properties that have tenants or have had a tenant within the last seven years. It also delays implementation in “sensitive communities” at risk of displacement until 2025, giving these areas from 2020 to 2025 to develop community-led plans to address growth and displacement. These communities would be determined by HCD based on factors like percentage of tenants below the poverty line, although it’s otherwise unclear how HCD would determine them. Finally, the bill includes minimum affordable housing requirement for projects requesting these local waivers (although that percentage is not yet determined yet in the bill).

With these changes, Sen. Wiener has already expanded the initial coalition in support — or at least not opposed at this point. For example, the powerful State Building & Construction Trades Council of California is supportive, as the bill explicitly allows existing local wage standards to remain unaffected. And tenants’ rights groups like Strategic Actions for a Just Economy in Los Angeles have not opposed the bill yet and have been in ongoing discussions with Sen. Wiener’s office. It otherwise seems inevitable though that the League of California Cities will oppose. So the question will be: will the coalition in support be powerful enough to override wealthy communities and their elected representatives, who will inevitably oppose?

In terms of the bill’s effectiveness, like SB 827 it would be a monumental shift in California housing policy that would address one of the core impediments to new housing construction: restrictive local zoning in job-rich areas.

Yet two provisions could undermine its effectiveness greatly, depending on how they are shaped during negotiations. First, the requirement to include a percentage of affordable homes in the buildings could render the provisions meaningless if that percentage is too high. For example, San Francisco’s voter-mandated inclusionary percentage of 25% affordable units for new development projects has contributed to a significant recent decrease in building permit applications (although other factors are at play as well), as SPUR recently documented.

In addition, placing off limits “sensitive communities” could also greatly limit its applicability without stricter and clearer criteria on how HCD will determine these communities and a sense of how many communities would be taken off the table. Otherwise the concept at first glance appears sound, as a way both to minimize opposition and reduce displacement risks in high-priority areas.

But overall, the bill retains the promise of SB 827 with a more inclusive process to bring on board more supporters. If SB 50 passes in something like its current form, it holds the potential to address the state’s housing shortage (and the emissions that result from long commutes from job-rich but housing-poor areas) in a fundamental way.