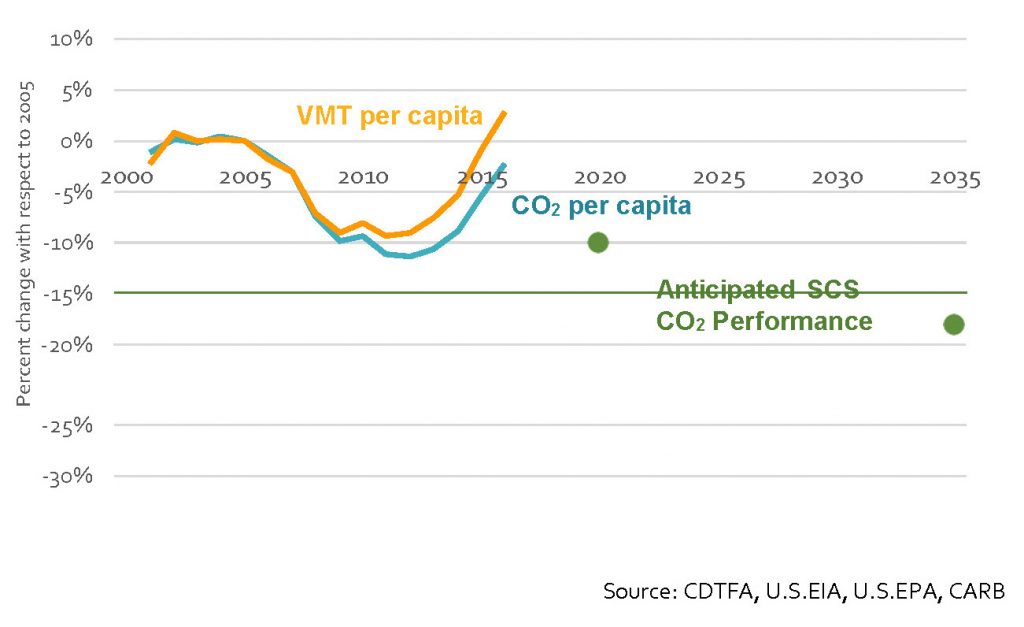

California’s major urban regions are falling behind in getting people out of their solo drives in favor of walking, biking, transit and carpooling, according to a major report last month from the California Air Resources Board. In short, the state will not meet its 2030 climate goals without more progress on reducing vehicle miles traveled (VMT):

This result comes despite the decade-old passage of SB 375 (Steinberg, 2008), which promised to reorient land use and transportation around reduced driving. The lone exception appears to be the San Francisco Bay Area, which has seen steadily increasing transit ridership and decreasing solo driving to work as a percentage, according to the report.

This result comes despite the decade-old passage of SB 375 (Steinberg, 2008), which promised to reorient land use and transportation around reduced driving. The lone exception appears to be the San Francisco Bay Area, which has seen steadily increasing transit ridership and decreasing solo driving to work as a percentage, according to the report.

What are the stakes if California can’t start solving this problem in the next decade? A U.N. report on climate change recently concluded that limiting global warming to 1.5 C would “require more policies that get people out of their cars — into ride-sharing and public transportation, if not bikes and scooters — even as cars switch from fossil fuels to electrics.” In order to keep the world on track to stay within 1.5 Celsius, the report stated that emission reductions would have to “come predominantly from the transport and industry sectors” and that countries couldn’t just rely on zero-emission vehicles alone.

Yet as the report shows, California’s current land use policies are not helping with this goal. We need to discourage development in car-dependent areas while promoting growth close to jobs, as SB 50 would allow. And at the same time, we need to invest in better transit service. Otherwise, California and jurisdictions like it around the world will fail to avert the coming climate catastrophe.

When SB 375 (Steinberg) passed in 2008, it got a lot of press as a fundamental change in transportation and land use in California. The law would now require regional transportation investments that promote smart growth, with the state setting a metric target for each region to reduce greenhouse gas emissions through less driving.

When SB 375 (Steinberg) passed in 2008, it got a lot of press as a fundamental change in transportation and land use in California. The law would now require regional transportation investments that promote smart growth, with the state setting a metric target for each region to reduce greenhouse gas emissions through less driving.

The law had some immediate problems though, which I outlined after the first regional transportation plan under the law was unveiled in San Diego in 2011. Namely, SB 375 failed to compel any changes in local land use policies, which is where the ultimate authority for permitting new housing lies (the state’s local government lobby added a provision to the original bill that the sustainable transportation plans would not affect local government land use plans).

Now a new National Center for Sustainable Transportation study [PDF] that surveys local land use responses to SB 375 confirms this weak impact on local decision-making. The authors surveyed planning departments in all cities and counties in California regions subject to SB 375 and received 180 responses out of 474 contacted. The found:

A majority of both county and city planning managers report that SB 375 had little to no impact on actions by their city to adopt or strengthen the eight smart growth strategies asked about in the survey. Responses to this effect were especially pronounced for the use of urban growth boundaries and of ag-land and open space preservation, suggesting that cities may have been motivated to support such strategies for other reasons, perhaps even before SB 375.

To be sure, the study highlighted some positives from SB 375 for local governments, primarily related to increased information sharing among them:

At the same time, a majority of cities and counties report that SB 375 has led to increased communication among local governments and other actors about land use issues and has led them to participate more in the regional planning process.

But ultimately the law fails fundamentally to change local government behavior:

When asked about the eight smart growth land use strategies, relatively few local governments anticipate that SB 375 will have a substantial impact on their cities in terms of specific costs or benefits.

In the end, SB 375 will not be a game-changer by itself but a policy foundation upon which more meaningful legislation can build. Examples of more impactful legislation include SB 743 (Steinberg, 2013) and this year’s SB 35 (Wiener, 2017). SB 375 provides some conceptual underpinnings and data to support these newer laws. But without any direct tie to local decision-making, SB 375 as it currently stands will not by itself solve California’s land use and transportation challenges.

That question is at the heart of SB 375 (Steinberg), California’s supposedly landmark land use and climate change law passed in 2008. It was a complicated law, but in short it required regional transportation plans to direct more transportation dollars to infill areas, in order to meet state greenhouse gas targets. It included some regulatory streamlining as well for development projects consistent with that plan.

It was a worthwhile idea. After all, approaching land use issues in metropolitan areas at a regional scale makes a lot of sense. We should be spending dollars where the most people can live and work, and not encouraging sprawl by investing in outlying transportation infrastructure.

But the problem is that land use and transportation decisions are mostly made at the local level. On land use, cities and counties have virtually complete control over what gets built in their jurisdictions. They control the zoning and grant virtually whatever exceptions they want to that zoning. The state and regional entities have practically no authority over those decisions.

Transportation is more complicated, with the state raising and spending about one-quarter of the transportation dollars. But locals raise half the dollars statewide, and even when regional entities have decision-making authority over transportation funds, local elected officials are the ones who sit on those governing boards. The result is either weak regional plans or strong plans that are unlikely to be implemented.

SB 375 did nothing to change this dynamic and actually give decision-making authority to the regional entities producing these plans — or at least require local compliance. Not to mention that SB 375 gives regional entities much wiggle room to avoid making meaningful changes to comply with the state targets.

That’s why I’ve been gloomy about SB 375 from the beginning, wondering if it’s even worth it for smart growth advocates to invest much time in helping to implement the law.

Now we finally have an academic study to support this contention. Researchers at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign studied the effects on land use of Sacramento’s 2004 “blueprint” plan, which inspired SB 375. The results don’t look good, as the authors summarize (subscription required):

Unfortunately, we find that highly rated neighborhoods—those whose attributes were matched to Blueprint’s overall priorities—received relatively fewer residential units than did neighborhoods less aligned with the regional plan. Furthermore, on average, more residential development in the post-plan period occurred in less highly rated neighborhoods than before the implementation of the plan. We also find major differences in acceptance of the regional -planning principles in some jurisdictions than others; for example, Sacramento, with more opportunities for infill development, was more likely to adopt some of the regional plan principles, while smaller suburban communities with large tracts of developable land were more likely to build traditional suburban housing.

Mike McKeever, executive director of Sacramento’s regional entity, was understandably defensive about the study, as quoted in the Sacramento Bee:

[McKeever] countered that the report appears to have an anti-suburb bias. Greenfield or open space development can be consistent with Blueprint principles if designed correctly, he said. He also said it is too early to get a solid view of the effectiveness of the plan, which seeks to influence development patterns over a 45-year period.

“We never were delusional to think that everything was going to change on a dime,” McKeever said. Growth in the last decade has been unusual, he said, with a huge spurt of the early 2000s when pre-Blueprint projects were in the pipeline, followed by a complete collapse of home building in 2007.

Sure, it was a strange decade for real estate. And yes there were bad projects in the pipeline in 2004. But there are still bad projects in the pipeline today, such as Cordova Hills, a sprawl project referenced in the Bee article that the county approved despite its conflict with the Blueprint.

The real issue for smart growth advocates, as the study authors recognize, is how to influence local decision-making to implement these regional plans. Otherwise they will have minimal real-world value other than as nice planning exercises that may help already-sympathetic jurisdictions build a bit more infill.

It’s a tough political challenge given the power of the local government lobby, and it may require going city-by-city to organize residents and encourage good planning and implementation. It will also require work-arounds, such as through changes to the state’s environmental review law, the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), to evaluate traffic impacts of new real estate projects based on vehicle miles traveled rather than auto delay, as SB 743 requires. Advocates can also encourage better standards for evaluating new transportation projects to ensure they meet greenhouse gas and vehicle miles traveled goals.

Short of legislative amendments to SB 375, it will take this kind of creative problem-solving to make a difference. Because SB 375 alone won’t get it done.

As my Legal Planet colleague Rick Frank blogged, the California Supreme Court on Wednesday granted review of San Diego’s really bad regional transportation plan. I detail the history here, but basically San Diego’s regional transportation agency delivered a plan in 2011 that was supposed to comply with SB 375 (Steinberg, 2008), a landmark law linking transportation spending with long-term greenhouse gas emission reductions.

Instead, San Diego’s agency issued a plan that projected reductions in vehicle miles traveled only in the short run, via accounting gimmicks like more telecommuting and estimated smoother traffic flows from highway widening. And then the plan actually showed backsliding on emissions going out to 2050.

Petitioners argued successfully at the trial and appellate court level that this backsliding contravened California’s long-term policy on greenhouse gases, specifically Governor Schwarzenegger’s 2005 executive order calling for an 80% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions from 1990 levels by 2050. Notably, the state’s 2006 climate legislation, AB 32, only discussed a 2020 greenhouse gas target.

But will this case already be moot by the time the court decides it? There are two reasons to think so:

First, San Diego is already well into its second transportation plan in the post-SB 375 world, which presumably will be much stronger than its 2011 version. That version was already in process when SB 375 was enacted and was the first out of the gate in California to have to comply with the new law.

Second, the California Legislature is currently debating a series of bills that could solidify California’s long-term greenhouse gas emissions reduction goals. If those goals get legislated, particularly ones out to 2050, then a debate over whether the 2005 executive order is legally enforceable in this instance becomes moot.

Of course, a win for the plan’s opponents will only strengthen the hand of advocates for better, more sustainable transportation and land use planning. It will force SB 375 plans to contemplate real, meaningful changes in land use and transportation decision-making, because these greenhouse gas reductions will have to be permanent and cumulative. And it will bolster efforts by public officials in other contexts to reduce long-term greenhouse gas emissions in order to comply with the California Environmental Quality Act, which this case is based on.

So in the end, I hope the court upholds the lower court decision. But I also hope the case becomes moot with legislative action this year.

Back in 2011, the San Diego Association of Governments issued a really bad regional transportation plan. These plans must prioritize transportation investments across the metropolitan region for the coming decades and are the basis for receiving state and federal infrastructure dollars. And while most regional transportation plans are usually pretty bad (i.e. favoring highway expansion over core maintenance and transit/biking/walking infrastructure), SANDAG’s happened to be the first in the state to have to comply with SB 375, a law linking transportation investments with land use policies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. So it held even more significance.

Environmental groups, along with the California Attorney General’s Office, sued SANDAG under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), alleging that SANDAG inadequately considered the plan’s effects on greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. They argued that the agency should have taken those impacts into account given a 2005 executive order to reduce emissions by that year.

They had a strong case. To comply with SB 375, SANDAG essentially fudged the short-term numbers, relying on highway expansion and more telecommuting to reduce greenhouse gases through 2035. But by 2050, the plan actually showed increasing greenhouse gas emissions, out to a time when we need to be reducing emissions significantly. As a result, SANDAG lost in the trial court.

And today they lost the appeal. Judge McConnell of the Fourth Appellate District wrote the decision affirming [PDF] the trial court decision, sending the case back to the trial court for SANDAG to beef up its analysis of the 2050 goals and the range of options the agency has available to comply:

As evidence in the record indicates the transportation plan would actually be inconsistent with state climate policy over the long term, the omission deprived the public and decision makers of relevant information about the transportation plan’s environmental consequences. The omission was prejudicial because it precluded informed decisionmaking and public participation.

Judge Benke wrote a fiery dissent, calling the court’s decision “breathtaking” in its judicial overstepping into local planning matters. But the reality is that SANDAG needs to own up to the backsliding in emissions by 2050 and provide the public with a reasonable range of options to avoid this outcome. It fundamentally failed to do so in the first round. Even if some of those options might seem politically difficult (like asking rural or exurban areas to take a backseat on highway expansion in favor of investing in the populated core areas), SANDAG should lay it out there for people to understand.

Regardless, SANDAG’s next transportation plan (already well underway) should be a vast improvement. In fairness to the agency, they did not have much time to incorporate SB 375 goals into the original plan, which was already being written at the time SB 375 passed. But the agency has now had four years to do so for the next plan. So SANDAG has no excuse to avoid improving the CEQA document on the old plan and coming up with a decent new plan.

Perhaps more importantly, the case has served an important political role in letting other regions know that they need to do a solid job complying with SB 375. Nothing wakes an agency up like a lawsuit, and advocates have been able to leverage the threat of a lawsuit to encourage meaningful changes in transportation plans across the state since the SANDAG plan. So in that sense, the case was already a victory for advocates even before today’s ruling.