As I began researching the history of the Los Angeles Metro Rail system for my 2014 book Railtown, one particular aspect of the rail transit story shocked me. No, it wasn’t the petty political squabbles, short-sighted civic leadership, or selfish parochialism that slowed, weakened and sometimes stymied the development of a functional rail system in Los Angeles. It was the shocking price tag of building rail transit — particularly tunneling under busy city streets — and the absurd amount of time (decades in some cases) to dig tunnels that more than a century ago were done in a fraction of the time it takes today.

Like the rest of the United States, Los Angeles suffers from exorbitant costs and delays with tunneling. The 1.9 mile Regional Connector light rail tunnel under downtown, for example, will cost almost $1.7 billion and take at least 8 years to complete. Nationwide, as transit expert Alon Levy has documented, tunneling costs are out of whack even compared to other developed nations, with New York City’s $2.6 billion-per-mile Second Avenue subway as a particularly gruesome transit horror story.

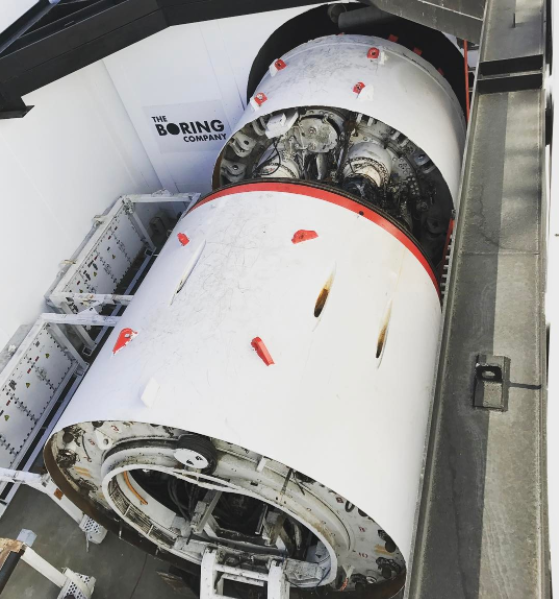

So I was intrigued this past December when I learned that Elon Musk’s Boring Company was unveiling a demonstration tunnel in Hawthorne, California, that could be built quickly and at a fraction of the cost. How cheap? 1.14-mile for just $10 million, with potential long-term improvements in speed of up to 15 times over the current rate.

Many urbanists sneered, deriding the tunnel as nothing more than a sewer pipe and mocking the idea of a “tunnel for Teslas” as simply recreating the failed surface roadway patterns of the present — or worse, catering to the wealthy by allowing them to avoid the congestion caused by the plebeians above.

Many of these same urbanists already resented Musk for his work with Tesla, a company which promotes a vehicle technology that they rightly identify as destroying our urban fabric, while he also (ironically) works to remove one of the arguments against cars by eliminating their tailpipe pollution.

But what if Musk and his rocket scientists from SpaceX really could bring down the cost and time of tunneling? Imagine the transit projects that could ensue. I’ll offer four, just here in California alone:

- A subway under Wilshire Boulevard in Los Angeles, the densest corridor west of the Mississippi, while Metro, the public agency currently trying to build one, is mired in a decade-long, multi-billion dollar slog.

- A subway connecting West L.A. with Sherman Oaks and the San Fernando Valley underneath the dreaded Sepulveda Pass and the freeway parking lot known as “The 405.”

- A second Bay crossing connecting Oakland and San Francisco to address congestion on BART and possibly allow one-seat train service from San Francisco to Sacramento.

- A tunnel connecting San Francisco to Los Angeles and San Diego, completing the dream of the flailing high speed rail project.

Those four projects alone would make any California urbanist happy. Yet how seriously can we take the Boring Company’s claims regarding decreased tunneling costs and time?

I took a tour of the test tunnel in Hawthorne last month to try to gain more clarity on how the company is reducing tunnel costs. Three things stood out:

- The Dirt. Believe it or not, what to do with the dirt that comes out of tunnels is a big limiting factor. I heard this first-hand from the tunneling experts working on the Regional Connector project under downtown Los Angeles. Yet the Boring Company may have found something simple and innovative to do with that dirt: turn them into functional bricks. To prove their point, they built a Monty Python-style tower out of the bricks on site. If the bricks can be given away for free, it will greatly reduce costs. If they can sell the bricks for use in things like sound walls, they say they could actually make money on the tunnel (see the picture above and video below of the dirt brick-making process).

- Private funding incentives. The Boring Company is envisioning a privately funded network of tunnels throughout California and beyond. They are not necessarily contemplating bidding on large public sector contracts. As a result, the company appears to have incentives to cut costs in ways that some of the few big tunneling companies competing for select large public contracts may not. As an example, the company can save costs simply in terms of where they manufacture the tunnel’s concrete segments relative to the tunnel, a cost-saving step that they say the big tunneling contractors aren’t financially motivated to take.

- Lots of little things. There appears to be no one single leap forward with the Boring Company machine. But instead, the company’s leaders say they’ve managed a series of smaller innovations that combined together could help reduce the costs dramatically. Perhaps most significantly, the tunnel bore has a smaller diameter than many rail tunnels because they don’t need the wiring and infrastructure that a train needs, but it’s still large enough to fit a vehicle with the carrying capacity of a subway train. Their vision is to run battery-powered, autonomous vehicle platforms in the tunnels, rather than hard wire expensive rail cars. It’s a vision of where technology is heading that could eventually lead to existing rail transit being converted to autonomous, battery-powered, platooning shuttles, which could carry the same passengers as rail but for a fraction of the capital and operating costs.

In any event, we’ll soon see if these company claims are accurate, as the Boring Company appears ready to work on a tunnel under the Las Vegas convention center soon.

And while urbanists fret about the potential for expanded subterranean capacity for solo drivers, there’s no reason that the technology would only be employed for that use and couldn’t scale to the level of current public rail transit. The company sees Model X battery-powered platforms seating between 16 and 32 passengers traveling up to 165 miles per hour through LED-lit tunnels. And with five boring machines in action, they think they could reach San Francisco in just a year. That vision — though of private and not public transit — would only bolster urbanist goals of car-free living in more dense, transit-oriented communities.

A big limiting factor though, beyond the technology, may be permitting. Environmental review under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) may slow this deployment. Under the law, permitting agencies will have to study and mitigate environmental impacts ranging from paleontology to induced land use changes and traffic at the surface entry points to the tunnel. We’ll see how that process plays out, if the Boring Company starts moving forward on a project in California.

But if Musk and his crew have actually solved the technology and cost problem of tunneling, they will have given transit backers throughout the United States and beyond a big reason to celebrate. Because a revolution in tunneling is a pipe dream worth pursuing in our increasingly urban world.

Map of the regional connector. Staging area was by the 1st and Central station on the right.

What’s a transit line without a tunnel? For densely populated areas, digging a tunnel can bring badly needed new capacity to congested corridors, while promising quick speeds underneath crowded roads. Plus tunnels represent interesting engineering and construction projects.

So when Jody Litvak of LA Metro invited me for a tour of the regional connector tunnel last spring, I jumped at the chance. At the time, the regional connector was under construction underneath Downtown Los Angeles, as you can see in the map above. I wrote about tunneling in Railtown, my book on the history of Metro Rail (I actually devoted a whole chapter to construction). But I’d never seen it up close until this tour.

I met Jody and her team at the staging area near Alameda and 1st Street in downtown. Olga Arroyo helped arrange the details, Dick McClane was the lead tunnel operator, and Bill Hansmire, Gary Baker and Glen Frank came along for the tour. Dick helps control the tunnel boring machine from a command center that resembles a miniature air traffic control tower. He monitors and corrects the machine’s every moment, using a complex network of sensors.

Dick also helps oversee the workers who do the tunneling. They call themselves “miners” — not “tunnel stiffs,” as the original tunnelers called themselves who built Metro Rail back in the 1980s, as I wrote in Railtown. The work is not for everyone: the miners described to me how some first-time workers have panic attacks when they get in the tunnel and simply can’t do the work.

But the regional connector and other train tunnels are actually a luxury — in the tunneling world. Many tunnels they work on are tiny and go miles deep, such as for sewers or other pipe infrastructure. The workers have to journey in the whole way on a makeshift train, leaning over to speed through the narrow tunnel. By comparison, this was a big, convenient tunnel. But still, there’s no daylight down there, so it’s a challenging work environment, and the miners work long shifts — sometimes 24 hours, 5 days straight on multiple shifts (with downtime in between, of course).

As the tour kicked off, safety was a priority. We were outfitted with helmets and reflective gear and instructed on proper procedures in the tunnel. Upon approach, the first thing we saw was the multi-block, fenced-off project site. The main feature was a conveyor belt from the shaft below, bringing up dirt that probably hadn’t seen the light of day in centuries, to be hauled off to help bury landfills. It created a huge pile that was actually just a couple days’ worth of excavation (see photo to the left).

The crew used this staging area to avoid disruption to the community from truck traffic coming out of tunnel. All that dirt requires a lot of vehicles to move it out of the area. In fact, truck traffic could be a limiting factor on tunnel boring, even if Elon Musk and his “Boring Machine” could speed the physical tunneling process.

Also visible up above were stacks of preset concrete slabs to line the tunnels, along with temporary steel rails. The rails help bring materials in and out of the tunnel, as they are hoisted down by crane and brought into the tunnel by temporary rail cars to lay more track.

We then journeyed down from the staging area to the giant shaft in the shape of the eventual station box. It had steep, temporary stairs leading down to the future station bottom and tunnel entrance. At the bottom, we could start walking through the actual tunnel.

Getting close to the tunnel, we could see lots of utility lines through pipes above us, including an old aqueduct from original the original Pueblo settlement. As the workers told me, these “station boxes” are where they find all the archaeological finds. Otherwise, the boring machine pretty much grinds everything else up (although evidently the formation that the tunnel passes through doesn’t typically have archaeological finds). For more on the archaeological finds in the tunnel, check out this article.

Inside the tunnel, it was hot with an odd smell. It was loud, too, particularly when workers dropped new 30-foot steel rails to the ground. The rails were needed for the temporary cars that brought in equipment. The tunnel boring machine (“TBM”) itself was probably about 100 yards long. In fact, it was so long, I was walking through it for a while without even knowing it.

The TBM is operated by four people: an operator, engineer, and mechanic, along with an MTA inspector. The machines have sensors everywhere and are extremely high-tech, monitoring the ground movement above. The software can automatically brake the TBM if the machine starts going in the wrong direction. The TBM uses pressure within the tunnel to maintain the pressure in the ground around the tunnel as it’s bored. That stabilization reduces, if not eliminates, both ground subsidence and gas seepage into the tunnel. For example, at the time of the tour, we were directly under a Japanese market in Little Tokyo. Hopefully, the patrons up above had no idea what was going on below. Sometimes TBM workers have to tunnel quickly through some parts of the city, like through certain soils that aren’t as solid.

Progress was steady: the miners were clearing about 80 feet in one day, at an average of 65 feet. They were starting with just the “left” bore for now, drilling it out for one mile, then hauling the tunnel boring machine (TBM) back to the project site and reassembling it for the “right” bore in the same direction, to create two tracks for the line. Overall, the first tunnel was set to take 5 months to go the whole 5,000 feet, 2 months to reassemble, and then another 5 months for the other tunnel.

In terms of cost, the tunneling represented only 10% of the total project cost. The station boxes are the other big chunk of change, particularly the future Bunker Hill stop, because it’s so deep.

Overall, it was an interesting opportunity to see digging in action. The project is scheduled to be finished in 2021. Once I ride it, I’ll end up whizzing through the section I walked. But I’ll now know how much work went into building it.

If you want more tunnel tour accounts, check out Curbed.LA from July and then again last month.

San Francisco and Los Angeles are both building subways below their downtown cores. And now both cities’ projects are over-budget and late. As Matier & Ross report in the San Francisco Chronicle:

San Francisco’s already behind-schedule Central Subway won’t be completed until 2021, more than a year later than the city insists the line will be ready, according to a new report by the big dig’s main contractor.

Construction giant Tutor Perini Corp. also says the $1.6 billion project is running tens of millions of dollars over budget.

Adding insult to injury, the former head of the agency that oversaw construction of the Transbay Transit Center, which went horribly over budget, is apparently lobbying the city for more money for Tutor Perini. The delay means the line won’t be able to serve the new Golden State Warriors arena for the first two seasons. For their part, city officials seem to think the contractor is bluffing to get more money. Either way, it’s not a good sign.

Meanwhile, in Los Angeles, the downtown regional connector light rail line is also in trouble, as Laura Nelson reports in the Los Angeles Times. The new opening date is now December 2021, a year later than the agency’s original target date of December 2020. Its $1.75-billion budget is now 28% higher than originally forecast.

Residents in these two major cities are now spending a better part of a decade watching these relatively short rail lines get built, at increasing taxpayer expense. While I’m sympathetic to the challenge of building under old urban environments, I wonder how much of these challenges should have been foreseen. It’s almost a joke at this point that elected officials over-promise on cost and timelines to sell new rail lines at the outset. But it would be nice to see those those promises actually come true for once, especially for transit projects as important as these.

Curbed LA writes about a partial court victory for downtown LA businesses that object to the “cut-and-cover” tunneling method in LA’s new regional connector light rail line. The line will travel through downtown LA, providing a badly needed link between the light rail lines ending at Union Station and beginning at the Blue/Expo Line stations not far from Staples Center in downtown. Right now, riders need to transfer to the heavy rail Red Line to connect, which adds a lot of time and hassle given the layout of Union Station.

Cut-and-cover is the cheapest way to tunnel: builders basically dig a trench in the road and then cover it with temporary decking to allow cars to drive above. They lay the rail tracks in the trench and then permanently pave the roof. The alternative is expensive and slow tunnel boring machines, which don’t disrupt above-ground activity (except where the machines enter and exit the earth) but add huge costs. Readers of Doug Most’s book on the New York and Boston subways will remember that cut-and-cover was the method used in both cities (with the exception of one part of the New York line). It partly explains why it was so much cheaper to build those systems, even adjusted for today’s dollars, than LA’s subway project, with its tunnel boring machines.But New York and Boston’s experiences also point to the political drawback of “cut-and-cover”: businesses on the ground hate it. It’s tremendously disruptive. In Boston, those businesses were politically weak, and their objections were overruled. The trenching was disruptive, but construction finished quickly and relatively inexpensively, with long-term gain. In New York, by contrast, the downtown businesses were powerful and ultimately successful, forcing a rerouting of the subway. But it got done with cut-and-cover.

Given the high cost of tunnel boring machines, I’d love to see transit agencies like Metro get the courage to go for cut-and-cover over the objections of local businesses. The savings for taxpayers are enormous, and perhaps some of those savings can be used to compensate the local businesses for any economic losses. And of course, the trenching should be done with the least disruption for those businesses as possible.

Based on the write-up of this decision, it sounds like Metro won’t have too much trouble justifying its cut-and-cover decision and complying with the court order. But the lawsuit points to the political challenges of trying to save money on rail lines. Powerful opponents and can force expensive changes that cost these lines political support. Ultimately, these political construction decisions deprive the rest of the city of the funds needed to build and maintain other needed transit lines.