Following the state legislature’s landmark approval extending California’s cap-and-trade program through 2030 by a supermajority vote, Berkeley Law’s Center for Law, Energy & The Environment (CLEE) and our research partners have completed the first comprehensive, academic study of the economic effects of existing climate and clean energy policies in Southern California’s Inland Empire.

Following the state legislature’s landmark approval extending California’s cap-and-trade program through 2030 by a supermajority vote, Berkeley Law’s Center for Law, Energy & The Environment (CLEE) and our research partners have completed the first comprehensive, academic study of the economic effects of existing climate and clean energy policies in Southern California’s Inland Empire.

Together with UC Berkeley’s Center for Labor Research and Education, and working with the nonpartisan nonprofit Next 10, the study found that between 2010 to 2016 the Inland Empire received:

- an estimated net benefit of $9.1 billion in direct economic activity and

- 41,000 net direct jobs, some of which are permanent and ongoing and many of which resulted from one-time construction investments.

Join the report authors as we discuss our findings on a webinar next Tuesday. We’ll cover the impact of cap and trade, the renewables portfolio standard, distributed solar policies and energy efficiency programs and their effects on the Inland Empire’s economy to date and going forward, as well as what these findings mean for other regions of the state and beyond.

In addition to yours truly, the webinar will feature:

- Betony Jones, UC Berkeley Labor Center

- F. Noel Perry, Next 10

The webinar will run from 10 to 11am on Tuesday, September 12th. Register now to join the discussion!

UPDATE: The webinar video recording is now available:

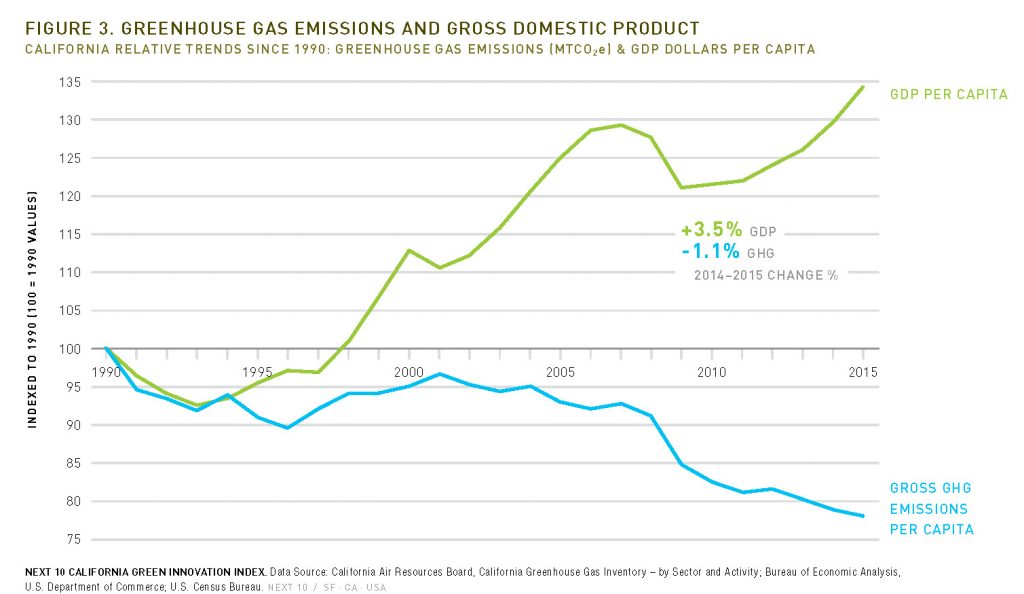

Next 10 has just released its handy annual report card on California’s climate and economic progress, called the California Green Innovation Index. The good news is that it shows carbon emissions in the state continue to fall while economic innovation and growth increases:

But the bad news is that transportation emissions are up:

But the bad news is that transportation emissions are up:

Despite an overall reduction in GHG emissions of 0.34 percent, transportation-related emissions were up by 2.7 percent in the state between 2014 and 2015. Lower gas prices and increased housing costs have pushed residents farther away from job centers, leading to an increase in commute times of 2.8 percent, while public transportation ridership fell 4.8 percent across the state.

The state can’t do too much about low gas prices (although the recent SB 1 gas tax increase will add a few pennies to each gallon). But it can facilitate more infill housing to lower costs and bring people closer to their jobs.

The problem though is the strong political opposition to reforms that would boost infill housing, which essentially involve taking away local authority over land use. The local government lobby and its wealthy homeowner allies have made prospects grim for making much progress on this critical climate strategy. Case in point: in a legislative session that was supposed to be the “year of housing,” the current proposals, while small steps in the right direction, are basically tweaks that have been effectively neutered by various interest groups.

As a result, the state’s main hope for reducing transportation emissions will be rapid electrification of vehicles. California is a leader on this front, but we’ll need exponential sales increases. That means a lot is riding on “mass market” vehicles like the Chevy Bolt and the upcoming Tesla Model 3 to be huge successes.

Bottom line: while California has a good story to tell on climate action, efforts to reduce emissions in the near term should focus on boosting electric vehicles and infill housing.

With the legislature just passing a landmark extension of cap-and-trade through 2030 by a supermajority vote, attention now turns to implementing the state’s major climate programs to achieve the ambitious climate goals for that year and beyond.

Critics frequently argue that efforts to fight climate change hurt the economy and cost jobs. Yet as I blogged about a few weeks ago, research on California’s San Joaquin Valley and then-forthcoming from the Inland Empire show net positive results.

The Center for Law, Energy and the Environment (CLEE) at UC Berkeley Law and UC Berkeley’s Center for Labor Research and Education, working with the nonpartisan nonprofit Next 10, just released the first comprehensive cost/benefit study of climate policies in Southern California’s Inland Empire, one of California’s most environmentally vulnerable regions.

The Net Economic Impacts of California’s Major Climate Programs in the Inland Empire: Analysis of 2010-2016 and Beyond examines the impact of four climate programs in the region, defined here as San Bernardino and Riverside Counties. We chose these counties as a follow-up to our San Joaquin Valley report due to the region’s environmental and economic challenges and because elected leaders from the area have asked questions about the impact of climate policies on their constituents.

The Net Economic Impacts of California’s Major Climate Programs in the Inland Empire: Analysis of 2010-2016 and Beyond examines the impact of four climate programs in the region, defined here as San Bernardino and Riverside Counties. We chose these counties as a follow-up to our San Joaquin Valley report due to the region’s environmental and economic challenges and because elected leaders from the area have asked questions about the impact of climate policies on their constituents.

The report analyzed not only the benefits of California’s climate and clean energy policies, but also compliance expenditures, investment expenses, and other costs.

After examining the data and using advanced modeling software, we found that the four key California climate and clean energy policies, including cap and trade, the renewables portfolio standard, distributed solar policies and energy efficiency programs (among the most important in California’s suite of climate policies) brought a net benefit of $9.1 billion in direct economic activity and 41,000 net direct jobs from 2010 to 2016 in the region, some of which are permanent and ongoing and many of which resulted from one-time construction investments.

We found that the overall benefits to the Inland Empire are likely to continue and grow through 2030, as the state strives to meet its newly legislated climate goals for that year, via SB 32 (Pavley, 2016), SB 350 (De Leon, 2015), and now AB 398 (Eduardo Garcia, 2017). Those efforts will require at least 50% renewables by 2030, a doubling of energy efficiency in existing buildings, and a robust cap-and-trade program through 2030.

Based on the findings in the Inland Empire, we suggest that policy makers wishing to continue these benefits focus on policies that reward cleaner transportation in this region, help disburse cap-and-trade auction proceeds in a timely and predictable manner, and create robust transition programs for workers and communities affected by the decline of the Inland Empire’s greenhouse gas-emitting industries, including re-training and job placement programs, bridges to retirement, and regional economic development initiatives.

You can access the full report via CLEE or Next 10’s websites and check out media coverage in Southern California’s Press-Enterprise and on KPCC, KFI, and KVCR radio.

California isn’t building enough housing to meet jobs and population growth, and what housing is getting built is happening too much in sprawl areas on greenfields. While this greenfield-focused development may please pro-sprawl conservatives, it will worsen traffic and air pollution and keep the state from meeting its long-term environmental goals.

California isn’t building enough housing to meet jobs and population growth, and what housing is getting built is happening too much in sprawl areas on greenfields. While this greenfield-focused development may please pro-sprawl conservatives, it will worsen traffic and air pollution and keep the state from meeting its long-term environmental goals.

To discuss where and what type of housing the state should be encouraging, please join me for an upcoming Berkeley Law webinar on May 17th from 11am to noon. We’ll be discussing the recent report from UC Berkeley Law’s Center for Law, Energy and the Environment (CLEE) and the Terner Center for Housing Innovation at UC Berkeley, commissioned by Next 10.

Right Type, Right Place is the first academic, comprehensive evaluation of the potential economic and environmental impacts of infill housing development — compact housing in already urbanized land near transit, jobs and services — on California’s 2030 climate goals under Senate Bill 32 (Pavley).

In addition to me, the webinar will feature:

- Nat Decker, researcher at the Terner Center for Housing Innovation

- Colleen Kredell, Director of Research, Next 10

Registration is now open. Please tune in and send us your questions!

With the release of the new report Right Type, Right Place, Capitol Weekly ran an op-ed from me and co-authors Carol Galante and Noel Perry this week, summarizing some of the benefits of an infill “target” scenario for new housing in California:

With the release of the new report Right Type, Right Place, Capitol Weekly ran an op-ed from me and co-authors Carol Galante and Noel Perry this week, summarizing some of the benefits of an infill “target” scenario for new housing in California:

The target scenario provides more housing that meets market demand for compact, walkable neighborhoods. While rents and home prices would be slightly higher in these neighborhoods on average, monthly household savings on commuting and other travel expenses, along with monthly savings on utilities, would more than make up the difference.

And infill has other advantages for our society. Switching from business as usual to the target scenario would save California 1.79 million metric tons of greenhouse gas emissions every year. That’s like taking 378,000 cars off the road; it would help us meet our climate change and air pollution goals. At the same time, our economy would fare better under the target scenario. Annual growth would be $800 million higher than under the business-as-usual scenario.

One benefit worth discussing but not captured in these economic and environmental metrics is quality of life. How do you put a dollar value on someone now having access to a decent home near high-quality jobs and in good neighborhoods? To being able to spend more time with family and friends and less in exhausting and expensive commutes?

Ultimately, infill is more than just about numbers. It’s about access to a better life for everyone, and the cleaner environment that goes with it.

For those who missed the webinar held by Berkeley Law on the new report Economic Impacts of California’s Major Climate Programs on the San Joaquin Valley, you can watch a recorded version here and below.

The report assessed the economic and employment impacts of California’s ambitious climate policies on the San Joaquin Valley, including cap and trade, renewable energy, and energy efficiency. In addition to me and moderator Jordan Diamond, the webinar featured:

- Betony Jones, UC Berkeley Labor Center

- F. Noel Perry, Next 10

The video runs about an hour. Happy viewing!

California isn’t building enough housing to meet population growth, while the new housing that does get built is happening too often in the wrong places, like on open space far from jobs. Meanwhile, new climate legislation for 2030 will likely rely on the average Californian reducing his or her driving miles by allowing residents to live closer to jobs and services.

So how do we reconcile these two trends?

Certain leaders in the building industry — primarily sprawl developers — have cried gloom and doom, claiming that the state’s climate goals will drive up costs for everyone and result in less housing getting built.

But a new report releasing today from UC Berkeley Law’s Center for Law, Energy and the Environment (CLEE) and the Terner Center for Housing Innovation at UC Berkeley, commissioned by Next 10, found the opposite result.

But a new report releasing today from UC Berkeley Law’s Center for Law, Energy and the Environment (CLEE) and the Terner Center for Housing Innovation at UC Berkeley, commissioned by Next 10, found the opposite result.

Right Type, Right Place is the first academic, comprehensive evaluation of the potential economic and environmental impacts of infill housing development — compact housing in already urbanized land near transit, jobs and services — on California’s 2030 climate goals under Senate Bill 32 (Pavley). We examined three scenarios: business-as-usual housing development, a “target” infill scenario with more multifamily and attached housing in close-in neighborhoods near rail transit, and a mixed scenario in between the two.

While the business-as-usual scenario results in more car-dependent housing farther away from jobs and schools, the infill target scenario meets the same demand, spurring economic growth with a much smaller carbon footprint. Target scenario benefits include:

- Annual economic growth that’s over $800 million higher than business-as-usual

- Annual reductions of 1.79 million metric tons of greenhouse gas emissions compared to the business-as-usual scenario, which is the equivalent of taking 378,000 cars off the road and almost 15 percent of the emissions reductions needed to reach the state’s Senate Bill 375 (Steinberg, 2008) targets from statewide land use changes

- Lower overall monthly costs for average households

Meanwhile, residents — both new and existing — would see significant quality-of-life benefits in the target scenario. More housing would be available close to good jobs, meaning shorter commutes in better neighborhoods, while existing residents would see more retail and services coming to their neighborhoods to accompany the new residential growth, further reducing overall driving miles.

But this development won’t happen on its own. It’s not because of market forces though. Most people would like a walkable neighborhood close to more amenities, and many households (particularly without children) simply don’t need a big suburban house, with all the upkeep and costs.

But local governments simply don’t allow this kind of housing to get built, and the state has been lax on trying to force their hands and address the housing shortage and traffic problems. Meanwhile, in under-performing markets near transit, the state has not provided local governments with the needed financing tools to jumpstart private investment.

As California lawmakers consider over 130 bills this year to address the state’s housing crisis, the report provides several recommendations for policymakers to consider, such as reducing barriers and increasing incentives for regions that generate infill housing, creating anti-displacement policies to protect affordable housing, and directing more funds towards public transit and affordable housing.

You can access the report via CLEE’s website or Next 10. So far, the report has gotten media coverage from sources such as the Los Angeles Times, San Jose Mercury News, and Sacramento Business Journal. I also co-authored an op-ed on the report in today’s Capitol Weekly, along with Next 10’s Noel Perry and Terner Center’s Carol Galante, which summarizes the findings.

Hopefully the report will inform housing debates going forward, resulting in a California that builds enough housing to meet environmental goals while benefiting the economy at the same time.

Next 10, a nonpartisan research entity (with whom I’ve worked on studies in the past), released a trio of reports that shows how California’s housing shortage and resulting high prices have chased middle class and low-wage residents out of the state:

-

California experienced a negative net domestic migration of 625,000 from 2007 to 2014. In other words, 625,000 more people moved out of California to other states than moved in to California from other states.

-

The vast majority of the out-migrants went to just five states: Texas, Oregon, Nevada, Arizona, and Washington.

-

California was a net importer of residents from 15 states and the District of Columbia from 2007 to 2014.

-

Californians 25 years of age and over that do not possess four-year college degrees accounted for over 469,800 out-migrants. However, California was actually a net importer of nearly 52,700 residents with a bachelor’s degree or higher.

-

California remains the top state attracting international migrants, many of which are low-income earners and those that have obtained a bachelor’s degree.

While conservatives love to blame environmental laws for gutting the industries that support these kinds of workers, the data indicate that high housing costs dwarfs all other taxes as a drag on these workers. For many of them, they’d rather take a lower-paying job in a place with cheaper housing than get paid more in high-cost California.

It would be great if conservatives (and progressives) would focus their ire on the policies that restrict in-state housing, namely local zoning and height restrictions and Prop 13.

I won’t hold my breath though.

If we build it, they will come. For many years, that was the mantra of rail transit planners. Just build the rail line, and development will happen around the stations. And then more people will ride, and the system will be a good investment.

But in California, too often that hasn’t been the case. Much of our prime real estate within an easy walk (half-mile) of urban rail lines has been wasted — a victim of bad planning, poor market conditions, and/or restrictive local zoning. As a result, recalcitrant California cities push new growth into outlying areas, sprawling over open space and farmland, increasing traffic and air pollution, and creating an artificial and extreme shortage of housing that drives up rents and home prices and squeezes businesses and residents alike.

Today the nonpartisan research organization Next 10 is releasing a report authored by the Center for Law, Energy and the Environment (CLEE) at the UC Berkeley School of Law that seeks to evaluate how well California is taking advantage of rail transit stations. Using existing data from such sources as Walk Score and the Center for Neighborhood Technology, CLEE developed a scorecard of 11 indicators, including factors like walkability, affordability, percentage of residents and employees who use transit, and number of jobs and households within 1/2 mile radius. We then used that information to grade 489 transit stations in 6 rail systems across the state, excluding commuter lines like Metrolink and Caltrain and Amtrak, but including L.A.’s bus rapid transit line given it’s rail-like qualities.

Today the nonpartisan research organization Next 10 is releasing a report authored by the Center for Law, Energy and the Environment (CLEE) at the UC Berkeley School of Law that seeks to evaluate how well California is taking advantage of rail transit stations. Using existing data from such sources as Walk Score and the Center for Neighborhood Technology, CLEE developed a scorecard of 11 indicators, including factors like walkability, affordability, percentage of residents and employees who use transit, and number of jobs and households within 1/2 mile radius. We then used that information to grade 489 transit stations in 6 rail systems across the state, excluding commuter lines like Metrolink and Caltrain and Amtrak, but including L.A.’s bus rapid transit line given it’s rail-like qualities.

The results are on a curve, with the top 50% of station areas receiving A’s and B’s, and the bottom 50% receiving C’s and D’s (the bottom 2% get F’s). Stations are divided by and compete within three place types (residential, employment or mixed).

We found that each transit system has successful stations, typically located in downtown-like environments with walkability and good connection to amenities. San Francisco’s MUNI light rail system scored the best on average, with the top performing station statewide at Market Street and Church Street.

Other notable findings:

- San Diego’s Gillespie Field Station, located in a car-dependent and otherwise barren wasteland, received an F—scoring poorly across the board.

- LA Metro Rail’s best-scoring station is Westlake/ MacArthur Park station, which scores high on diversity of destinations, walkability, transit access, and affordability, but gets a poor mark on safety.

- Sacramento’s Longview Drive and I-80 station is next to a major interstate and used primarily for park-and-ride services. It is the region’s lowest-scoring area in terms of fostering a vibrant transit neighborhood, with very low train use among local residents and workers.

- The San Joaquin Valley is California’s fastest-growing region but lacks rail transit. As a result, we analyzed key busy bus station areas instead, awarding them separate grades ranging from B to D.

Overall, Santa Clara’s VTA and San Diego’s MTS systems scored the worst in the state, with many auto-oriented, derelict station areas, including along highways. After MUNI, BART was second and LA Metro Rail and Sacramento RT were tied for third, in terms of highest average score. You can access all the materials for the report here.

So what can be done to improve scores? First, local leaders with stations in their jurisdictions should plan for and encourage thriving, walkable neighborhoods around the stations. Second, state leaders can help underperforming areas that lack a market for new development by focusing state investment and financing programs in those areas, such as through green bonds and tax-increment financing. Finally, transit leaders should condition any rail expansion on a local commitment to transit-oriented development around the stations, and they should consider reducing service to underperforming stations in order to better serve stations with thriving neighborhoods around them.

Without steps like these, we risk wasting rail investments and exacerbating the state’s environmental and economic challenges. Future growth in the state should be focused along our existing rail transit networks, instead of pushed outward along highways. Ultimately, the scorecard reveals which station areas we should emulate, and which ones policy makers should focus on for improvement.