As coal-fired power plants shut down, many Native American tribes are facing the brunt. I wrote earlier this year about the challenges facing the Navajo and Hopi Tribes, in particular, with the closure of a nearby plant.

As in many areas around the country, environmental advocates tout the jobs and economic prospects of solar PV as a replacement for lost coal jobs. To put that to the test, the Farmington Daily Times reported on the Navajo Nation’s first large-scale solar energy facility on the reservation. The 27.3-megawatt Kayenta Solar Project opened in June. The electricity is sold to the Salt River Project for distribution, with revenues funding local tribal programs.

As in many areas around the country, environmental advocates tout the jobs and economic prospects of solar PV as a replacement for lost coal jobs. To put that to the test, the Farmington Daily Times reported on the Navajo Nation’s first large-scale solar energy facility on the reservation. The 27.3-megawatt Kayenta Solar Project opened in June. The electricity is sold to the Salt River Project for distribution, with revenues funding local tribal programs.

The project has had some immediate jobs and economic benefits:

[Navajo utility spokesperson Deenise] Becenti said at the height of construction, there were 250 personnel with 195 Navajo workers.

The $60 million facility was built using a construction loan from the National Rural Utilities Cooperative Finance Corporation.

Revenue from the solar project will help NTUA extend electricity to several communities on the reservation, according to an October 2016 press release from the tribal enterprise.

Last year, NTUA [Navajo Tribal Utility Authority] finalized an agreement with the tribe’s Community Development Block Grant program to increase electrical services to 92 residences.

The tribal enterprise will use revenues from the solar project as matching funds for the grant, the release states.

[NTUA General Manager Walter] Haase said in an email this will be the first time most families will have electricity in their homes.

“Using revenue generated from the solar project gives us the ability to bring electric service to these communities and help dramatically raise the standard of living for our Navajo families,” he said.

Overall, it seems like a success story for a rural community transitioning from coal to renewables. And it’s only the start, as the article indicates there’s potential for expanding the solar farm.

While the bulk of the jobs here are probably temporary construction ones, further study could be useful to examine the full impact of the new facility. For example, the tribal programs funded by the solar revenue presumably create their own jobs and economic impacts, which could further offset the loss of coal jobs and revenue. Either way, this is a story worth keeping an eye on for advocates of transitioning to renewables in rural areas everywhere.

Donald Trump and his Republican backers have long railed against environmental laws and regulations that disfavor coal. Trump won in part by promising to bring back coal mining jobs.

Donald Trump and his Republican backers have long railed against environmental laws and regulations that disfavor coal. Trump won in part by promising to bring back coal mining jobs.

But like so many of his claims, the truth is more complicated. Coal mines and plants are shutting down around the country mostly due to cheap competition from natural gas, not from environmental protections.

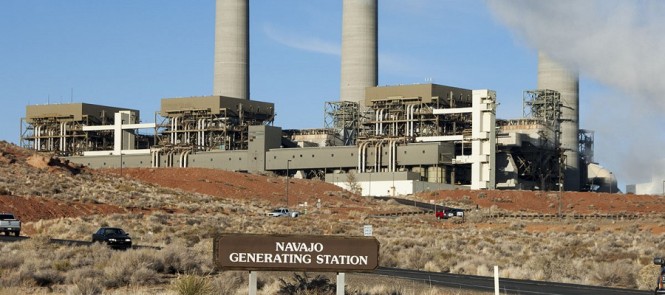

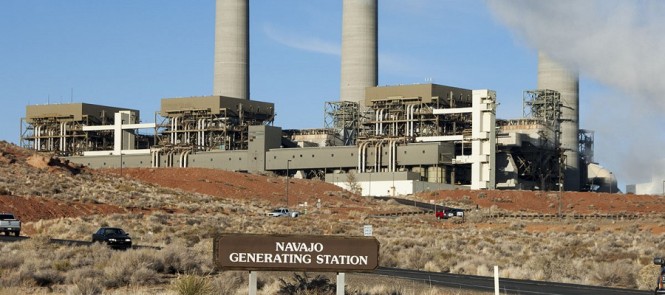

The big case in point, and coming at a bad time for Trump, is the announced closure of the Navajo Generating Station, one of the country’s largest coal-fired power plants.

The plant is located in Page, Arizona, near the Utah border, and is such a big polluter that it is responsible for much of the haze in the Grand Canyon, as well as a major source of greenhouse gas emissions. It provides 90 percent of the energy for the Central Arizona Project to pump water uphill from the Colorado River through a 336-mile canal to deliver water to Central Arizona farms, cities, and tribes.

For that reason, Central Arizona Project leaders were opposed to environmental regulations back in 2009 that would add costs to the station to make it run more cleanly. But now those leaders are changing their tune. In a blog post to his stakeholders, executive director Warren Tenney explained his change of heart about closing the plant:

Pure economics is driving the decision. The utilities that own [Navajo Generating Station] now are dealing with a power plant that is significantly more expensive than other energy options. Natural gas prices have dropped to record lows to become a viable long-term and economical alternative to coal power. This means pursuing the regulatory upgrades that were part of the compromise with EPA are even less cost-effective today. However, even if EPA loosened its coal regulations, the energy industry is headed towards having natural gas generation as the fuel of choice for many years to come.

In fact, the coal power is now so expensive compared to alternatives, Central Arizona Project leaders estimated they could have saved $38.5 million in 2016 had they bought power on the open market instead.

It’s a big test for the Trump Administration. Do they intervene to prop up this economically inefficient plant in order to make good on campaign promises? E&E [pay-walled] explored the options for them:

Washington is uniquely positioned to help. The government owns a 24.3 stake in NGS [the Navajo Generating Station] through the Bureau of Reclamation. When utilities announced the closure, Reclamation officials said the bureau would help identify options to keep it running.

But direct federal intervention to keep NGS running would amount to a stark reversal of previous policy, which largely focused on the idea of slowly transitioning the coal-reliant tribes toward renewables. Now, federal and tribal facilities face a ticking clock and an administration with a new set of priorities.

Complicating matters is that the plant is the economic lifeblood for the Navajo and Hopi Tribes, which receive significant income from the plant and coal mining operations on their lands. The Arizona Republic ran an in-depth piece exploring the impact of the coal mine on these tribal nations:

Hopi Chairman Herman Honanie has worked for tribal government since 1977. He said tribal members are split nearly evenly between support for the mine and closing it because of environmental concerns.

Hopi Tribe Chairman Herman Honanie

He sides with keeping the mine open.“The practicality is we have a growing population and we have growing needs,” Honanie said. “We have one foot in our culture and the other foot on the other side of dominant society and we are trying to mesh that together.”

Approximately 350 people who work for the tribe rely on the royalties from the mine for a significant portion of their paychecks. Those workers provide services from tribal courts to hospice care for the elderly.

The tribe anticipates $18.4 million in revenue this year, and more than $12 million of that will come from mining activities and from SRP for payments based on how well the power plant performs. Less than $2 million trickles in from court fees, business taxes, and investments in the KoKopeli Inn in Sedona, Three Canyon Ranch near Winslow and Moenkopi Legacy Inn near Tuba City.

I’ve worked with members of the Hopi Tribe since 2005 and have seen first-hand the impact of the coal-mining operation on the tribe’s finances. There are no easy answers once the operations cease, as renewables can only partially offset the employment and revenue losses.

But it will be incumbent on Arizona and tribal leaders, as well as the federal government, to blunt the impact of the closure on these communities. Rather than intervening to save the plant at tremendous environmental and taxpayer cost, they should develop an honest employment strategy — not just for Arizona but for the whole country — about how to replace these imperiled coal jobs and incomes with something sustainable and competitive.

As in many areas around the country, environmental advocates tout the jobs and economic prospects of solar PV as a replacement for lost coal jobs. To put that to the test, the Farmington Daily Times reported on the Navajo Nation’s first large-scale solar energy facility on the reservation. The 27.3-megawatt Kayenta Solar Project opened in June. The electricity is sold to the Salt River Project for distribution, with revenues funding local tribal programs.

As in many areas around the country, environmental advocates tout the jobs and economic prospects of solar PV as a replacement for lost coal jobs. To put that to the test, the Farmington Daily Times reported on the Navajo Nation’s first large-scale solar energy facility on the reservation. The 27.3-megawatt Kayenta Solar Project opened in June. The electricity is sold to the Salt River Project for distribution, with revenues funding local tribal programs.

Donald Trump and his Republican backers have long railed against environmental laws and regulations that disfavor coal. Trump won in part by promising to bring back coal mining jobs.

Donald Trump and his Republican backers have long railed against environmental laws and regulations that disfavor coal. Trump won in part by promising to bring back coal mining jobs.