Los Angeles County is a big place, with lots of urban centers to connect with rapid rail transit. Funding is limited for these expensive trains, despite the passage of two recent sales tax increases and two others passed in 1980 and 1990 respectively.

So why is the region spending these limited dollars on two rail lines in the mostly suburban, auto-oriented, low-density San Gabriel Valley? The issue is now front-and-center with the June approval of a $1.4 billion extension of the Foothill Gold Line light rail to Montclair.

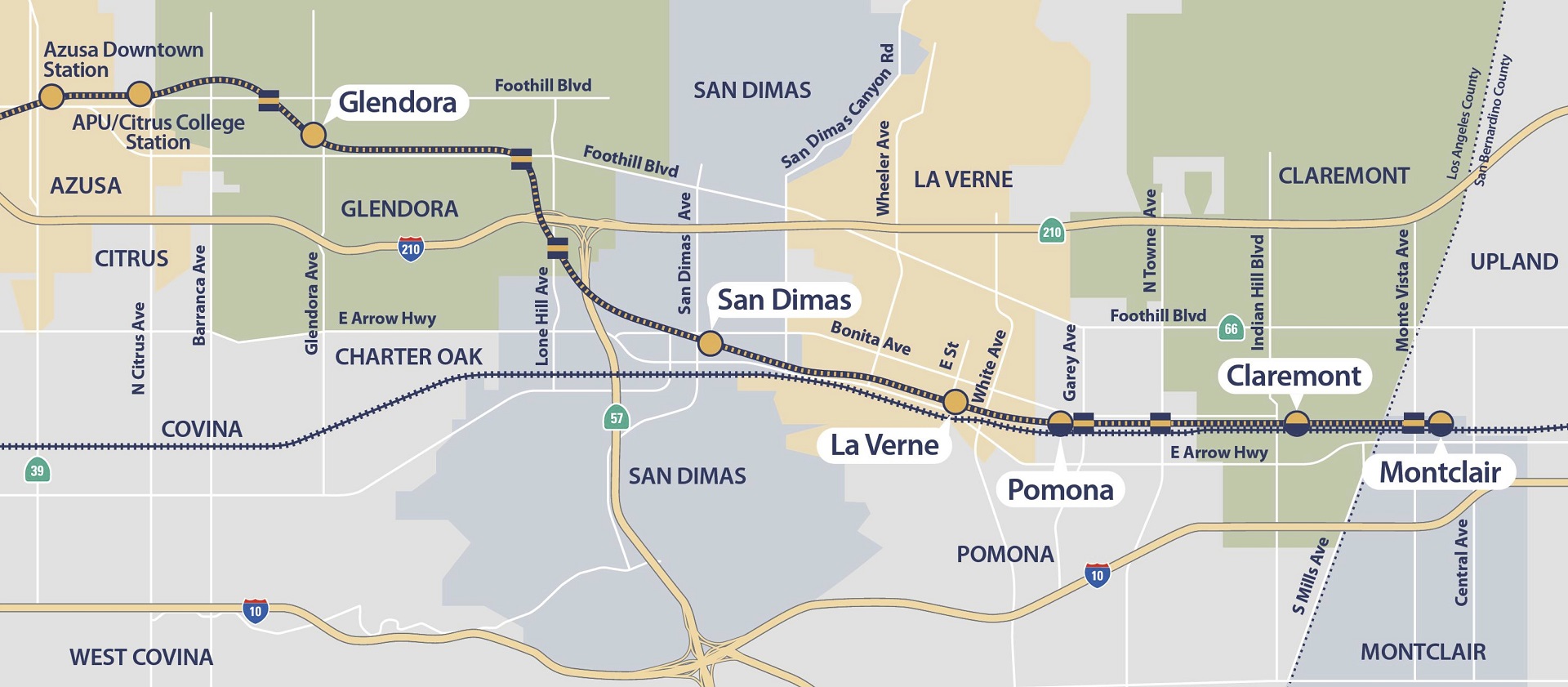

The problem is that the line dovetails with an existing Metrolink line, which is a diesel train for commuters into downtown Los Angeles. This map tells the story:

The existing Gold Line extension to Azusa already is cannibalizing nearby Metrolink service, as Urbanize LA reported:

In a report prepared for the Planning and Programming Committee, Metro staff notes that there has been a precipitous drop in ridership at a nearby station on the San Bernardino Metrolink line. In the year since the completion of the extension, which Metro calls the Gold Line Extension Phase 2A, boardings at Covina station have fallen 25 percent, despite being several miles from the Gold Line terminus at Azusa Pacific University.

Even more worrying for the future of Metrolink’s highest ridership line is the Gold Line Extension Phase 2B, which will extend the light rail line from Glendora to Claremont, and with a potential contribution from the County of San Bernardino, across the County line into Montclair. Three of the new stations, in the cities of Pomona, Claremont and Montclair, will be built in the Metrolink right-of-way and have stations directly adjacent to their commuter rail counterparts, offering perhaps an alluring alternative to the existing service. While Gold Line trains will take about 15 minutes longer to travel from Montclair to Union Station, they will be far cheaper and offer service every 7-12 minutes for most of the day.

I discussed this issue with KPCC radio recently, explaining that the reason for this extra rail service is simply politics. To secure two-thirds voter approval on the recent sales tax measures for transit, local leaders had to essentially buy off San Gabriel Valley leaders with a gold-plated rail line promise, even though the region doesn’t have the ridership to justify the expense.

That’s not to say that duplicative rail service is a bad thing by definition. If the population and job density is sufficient, two rail lines in proximity can make sense. But in this case, the density isn’t there. Metro leaders should have stood up to the San Gabriel Valley and funded a right-sized transit line. That would have most likely meant bus rapid transit and not light rail, which still would have been a big transit win for the region.

It may be too late to downsize the train route, but perhaps in the meantime Metro can develop adequate policies to ensure that San Gabriel Valley and Inland Empire leaders encourage maximum densities along the route. More dense development will not only give local residents more housing and commercial service options, it will provide more riders to minimize the losses on this unfortunate decision.

The Los Angeles Times has a depressing story on the ridership free-fall on Metrolink, Southern California’s long-haul commuter line:

The Los Angeles Times has a depressing story on the ridership free-fall on Metrolink, Southern California’s long-haul commuter line:

Once hailed as the fastest-growing commuter line in the nation, the railroad has seen its annual ridership drop by almost 595,000 passengers since 2008, with resulting losses in revenue. That and other factors have left the agency squeezed between trimming service or boosting fares, either of which could prompt more defections.

The article blames the recession mostly, but the head-on collision in 2008 and poor service with high fares seem to be huge factors, too. Overall, the biggest long-term problem may be the increasingly diffuse pattern of job growth in Southern California:

Studies indicate that the size of the workforce in the core of Los Angeles has stagnated somewhat in the last 20 years while the number of residents has tripled. At the same time, employment has risen in Orange County, the South Bay and on the Westside.

But only Orange County is served by Metrolink, and many new downtown L.A. residents tend to work closer to home and don’t need the rail service.

“The job growth is not that high in downtown Los Angeles,” said Brian Taylor, a professor of urban planning at UCLA. Metrolink’s “ridership is very sensitive to economic change and employment shifts.”

Employment density near transit is one of the most important factors driving ridership. While it’s great that downtown LA has seen a huge surge in residential density, city leaders should be concerned about job sprawl undermining transit ridership. Perhaps San Francisco can be a model, where Mayor Ed Lee made it a priority to attract new businesses/offices to the mid-Market area, leading to the “Twitter surge” that has transformed that long-moribund part of the city. Los Angeles leaders should make attracting new businesses to downtown a top priority. Not just for the benefit to Metrolink of course, but for the overall convenience it would add for residents to have easy, traffic-free access to their jobs.

Bob Hope Airport in Burbank unveiled a new transit center this week. The “Regional Intermodal Transportation Center” includes 11 rental car companies and a moving walkway to get passengers to the terminals.

But more importantly, it will feature an easy pedestrian connection to the Amtrak/Metrolink station right across the street from the terminals (see rendering on the right).

This easy rail connection is why I think Bob Hope Airport could be the high-demand air travel center for the region in the coming years. I’ve flown into Bob Hope and taken Metrolink to Union Station for an event before. It’s a pretty easy trip, but the walk along the airport accessway and across the street wasn’t great (see station photo on the left). Now a smooth pedestrian experience will make that experience much more seamless and efficient.

And more importantly, as Union Station becomes the center of the Metro Rail universe in Los Angeles, coupled with the resurgence of downtown LA, Bob Hope Airport will soon be your gateway for car-free access to much of the region. Even if LAX can get its act together with a people-mover automated train to the Crenshaw Line, passengers will still need to ride the slow Crenshaw line to the slow Expo Line to the Red Line or future Regional Connector to get to Union Station.

By contrast, Bob Hope will offer a faster, direct rail connection, without the hassle of the LAX craziness. So in the coming decades, I wouldn’t be surprised if Bob Hope may be your airport of choice for LA.

Longtime Angeleno Robert L. Davis is back with some follow-up memories of Pasadena rail. As an electric rail fan, he was excited back in the 1990s at the prospect of a new Metro light rail line to Pasadena, what would eventually become the Gold Line. However, he notes in the history that there was discussion of building it as part of Metrolink, the Southern California long-haul commuter rail that started in the early 1990s and shares tracks with freight lines:

Back in the early 1990s, when Santa Fe was in the process of selling of the 2nd District (LA to San Bernardino via Pasadena and Pomona), there was one school of thought among both SCRRA [Southern California Regional Rail Authority, which operates Metrolink] and Metrolink and a coterie of railfans that believed that the line through Pasadena should have been upgraded for faster operation, but should have remained a diesel-powered mostly single track line, which would accommodate both freight and passenger trains meeting FRA standards. This possibility was still under discussion one day when I was a volunteer trainman on a special train run by Orange Empire Railway Museum for SCRRA personnel. They wanted to see the Santa Fe San Jacinto Branch between Perris and Hemet, so we gave them a ride on our ex-Soo Line business car (which has played a political campaign car in movies). During the trip I heard the SCRRA folks discussing making the line through Pasadena a Metrolink route.

I covered the origins of the Gold Line in my book Railtown but did not discuss this possibility. Davis favored a non-diesel train, represented by light rail, over the smelly Metrolink option. I too favor electric transportation generally over diesel.

However, given the expense and amount of time it took to build the Gold Line, coupled with the relatively disappointing ridership numbers due to the slow route and lower population density of the corridor and San Gabriel Valley it serves, I wonder if going with the more expensive light rail was a mistake.

Metrolink was able to get up and running very quickly and cheaply, thanks in large part to a California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) exemption for new rail on existing freight rights-of-way and the easier infrastructure associated with commuter trains, as opposed to light rail (no overhead power lines, for example). It might have been a more appropriate technology for that corridor.

On the diesel vs. electricity issue, the California High Speed Rail Authority has plans to electrify Metrolink as part of the connection between Union Station and the Transbay Terminal in San Francisco (with the caveat that ongoing litigation may halt those plans). So ultimately, you might have had a cheaper system, up and running more quickly, with future plans to be electrified. With the freed up cash, L.A. Metro could have connected more neighborhoods to rail throughout the region.

Davis certainly wanted the line to be built more quickly:

Some of us had hoped that the Blue Line [as it was known then] to Pasadena would be done in time for the100th anniversary of the original electric railway from LA to Pasadena opening in 1895. As we all know, it took another eight years to make it happen, with all sorts of political goings on before any track was laid.

But many leaders from the area insisted on light rail, as the nicer, gold-plated option for their constituents. As I discuss in the book, the line had bipartisan federal support from Republican Congressman David Dreier, strong local support from Mayor Richard Riordan and Councilmember Richard Alatorre, and state support from then state legislator Adam Schiff. When Metro later went broke and couldn’t pay for the line, these powerful leaders removed the construction and financing from Metro in order to ensure it could get built. However, had these leaders been willing to explore different options for the corridor, perhaps passenger trains would have been running in time for that anniversary, and the region as a whole might have been better served as a result.