David Dayen in the American Prospect has a long piece describing the “revolt” in Los Angeles against the automobile and how the city is transforming before our eyes:

In January, the city received $1.6 billion in federal support for the Purple Line, and Mayor Garcetti has asked the Trump administration for more, to move up subway completion from 2035 to 2024, in time for that year’s Summer Olympics, for which L.A. is one of the two finalists. “We have become the infrastructure capital of the world,” says Phil Washington. “With two NFL teams, a rail spur to that stadium, the possibility of the Olympics, it creates this economic bonanza, what I call a modern-day WPA [Works Progress Administration].”

The risk, as Dayen points out, is that the Trump administration will withdraw federal funds, leaving Los Angeles to pay for much of this transformation on its own and essentially backfill the missing the federal dollars.

But cities have gone that way before. The Bay Area, for example, largely built BART on its own in the 1960s and 1970s, as the federal government didn’t provide funding for rail transit at the time.

The difference now is that costs have gone way up, making it harder for a region like Los Angeles to fund this transformation without getting its share of federal tax dollars back to reinvest locally.

The article also rightly points out (with some quotes from yours truly) that the great unanswered question is whether the region will allow growth to follow this new transportation infrastructure. Poor land use decision-making is what got the region into the mobility and air quality mess its in. Only smart growth near rail transit will provide residents the option of a way out.

But the necessary transit backbone, as Dayen describes, is finally coming into place, giving local leaders a viable foundation for rebirth.

For those in Los Angeles, I’ll be giving an evening talk on Wednesday, January 25th on the past and future of Metro Rail, based on my book Railtown. The event is hosted by UCLA’s Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies and will take place from 5:00 – 6:30pm in Room 5391 of the Public Affairs Building. It’s co-sponsored by the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs, Department of History, and Institute of Transportation Studies. More information and registration is available on UCLA’s event page. I’ll have book copies available for sale and to sign. Hope you can attend!

For those in Los Angeles, I’ll be giving an evening talk on Wednesday, January 25th on the past and future of Metro Rail, based on my book Railtown. The event is hosted by UCLA’s Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies and will take place from 5:00 – 6:30pm in Room 5391 of the Public Affairs Building. It’s co-sponsored by the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs, Department of History, and Institute of Transportation Studies. More information and registration is available on UCLA’s event page. I’ll have book copies available for sale and to sign. Hope you can attend!

And speaking of Railtown and UCLA, I’m belatedly sharing this 2016 review of the book by UCLA assistant professor of urban planning Michael Manville in the Journal of Planning Education and Research. Manville starts with some compliments:

This is a good book. Anyone who thinks they might like it probably will. Elkind is a talented writer and synthesizer of information, and the story itself is one that (for transportation nerds, at least) has long begged to be told. Elkind has scoured the archives and interviewed many of the participants in his story. I have lived in LA for more than ten years, studied transportation there, and rode many of its trains, and I still learned a lot reading Railtown.

However, he also offers some pointed critiques:

The book’s great weakness, to me, is that it takes rail’s necessity as a given. In doing so, Railtown assumes away the great unanswered question of modern rail: Why do we want it? What problem does it solve? There are times in Railtown…where rail seems almost an end in itself. Any proper city has rail, so rail is successful when we successfully build it. But in a city with scarce resources and vast needs, that is no way to justify enormous public expenditures.

It’s ironic to read this complaint because it is the exact mindset that I criticized early rail leaders for having in promoting rail. For me, rail is a necessity for Los Angeles because it provides the best transportation infrastructure around which to channel future growth in the city (with the big unanswered question as to whether or not local leaders will allow that growth to happen). Otherwise, future growth will either be disorganized and stuck in urban gridlock or pushed out as car-dependent sprawl. And at the densities that Los Angeles would need to build new housing to meet market demand and accommodate existing and future residents, only rail can efficiently move those large numbers of people (again, assuming the density comes to fruition).

It’s also worth mentioning that a corridor like along Wilshire Boulevard already has the density needed to support rail and is a prime candidate for such a project as-is, just given the existing conditions there.

Manville then continues with the critique that rail won’t address the region’s underlying transportation challenges:

More train riding is not the same as less driving. Why should LA (or any city) descend into debt to subsidize rail when it could just stop subsidizing cars? Angelinos drive as much as they do because their government routinely widens roads, requires parking with every new development, and most of all lets drivers use the city’s freeways and arterials—some of the most valuable land in the United States—for free. The projects described in Railtown are distractions from, not solutions to, these problems.

I wholeheartedly agree with Manville on this point. If the goal is to reduce traffic congestion, rail is not the answer, and I never make that claim in the book. The preferred solutions for addressing the traffic problem in Los Angeles would involve congestion pricing and ending subsidies for driving, as Manville describes.

But there’s no reason why the region can’t do both: build alternatives to driving like rail transit and also stop subsidizing auto driving. In fact, both are needed simultaneously, and I don’t see any evidence that rail distracted the public from these other solutions. The reality is that rail is the politically easier thing to do, so it gets done first. But subsidies for autos will be easier to remove once there is a viable alternative in place, so rail could provide the conditions necessary to earn public support for the steps Manville envisions. After all, San Francisco was able to stop subsidizing cars and become a “transit-first” city only after it developed a robust transit system, which included BART.

Overall, I agree with much of the book review and appreciate Manville’s comments. You can read the whole thing and come to the talk on the 25th to discuss and hear more!

Yesterday was the anniversary of the 1986 groundbreaking on L.A.’s Red Line subway, for its initial 4.1 mile segment from downtown. On the video below, you see many of the prime actors who made L.A. rail happen, from Mayor Tom Bradley to transit officials like Marv Holen and Jan Hall.

What stands out to me though is how off some of the predictions were. Dyer, for example, predicted that in 40-50 years there would be “40-50 miles of subway,” with 110 miles of light rail. He thought they’d all be in place in 10 or 20 years. Instead, almost 30 years later we have only 18.6 miles of subway, with just a 4-mile extension in the immediate pipeline, moving at a literal glacial pace. The system with light rail included totals 87.7 miles, albeit with some new lines opening in the coming years.

But perhaps Dyer could be forgiven. Rail was new in Los Angeles at the time, and nobody anticipated how bogged down planning and construction would become. But it points to how painful it has become to implement these projects.

Meanwhile, enjoy this funky 80s video of the groundbreaking festivities:

He tries to go transit-only on a recent business trip and ran into some trouble:

That afternoon, when I was done at the Hammer, I planned to take the 534 Commuter Express bus to Mark’s office downtown on South Figueroa Street. This, I was told, was a larger and more comfortable vehicle than the standard city buses: more conducive to the business traveler. I checked the sign at the stop: Sure enough, it listed the 534. So I waited. Buses of various colors and shapes came and went. After about 45 minutes, I asked a young woman who was also waiting if she was familiar with the bus. She looked at the sign and giggled. “The 534?” she said. “I’ve never seen that here.”

Dejectedly, I sat on a low stone wall at Wilshire and Westwood and called Mark. “I’ll be there in a little while,” he said. “I told you this wasn’t going to be easy.”

Minutes before he arrived, the 534 pulled in. I just glared at it.

It’s always good to see LA represented in the national media as having a burgeoning rail system and comprehensive bus network, but it’s a bit unfair to buzz in for a weekend with meetings all over the county and expect it to accurately represent the viability of local transit. I’m guessing if you tried to travel a comparable distance in a city like New York, you’d have trouble taking transit there, too.

But then again, maybe that’s the point: the land uses in LA or so spread out, it makes a comprehensive system of county-wide rapid transit infeasible and uneconomical. That’s why the region is better off focusing rapid transit efforts on places where the most people actually live and work. Had this reporter stuck to the primary jobs and housing centers, his trip would have been a lot smoother.

Ryan Reft takes a look at the histories of light rail efforts in both Atlanta and Los Angeles, showing how race, class and local opposition groups limited the effectiveness of both systems:

In both the case of the Blue Line and the construction of MARTA, charismatic, dedicated, and ultimately trusted political leaders fought hard for each and delivered. Could it be that simple, or have the ground rules changed so much that not even a [Los Angeles County supervisor] Kenneth Hahn or [Atlanta mayor] Sam Massell [could] deliver the goods today? In Atlanta at least, a coalition of “planners, hipsters, and other yuppies” haven’t gotten the job done. Perhaps, this time Atlanta should examine how L.A. and Kenneth Hahn managed to constructed a constituency large enough to build the light rail he dreamed of, which brought improvements to Compton and South Central, enabled suburbanites to travel between the region’s two biggest employment centers, and catalyzed award-winning transit-oriented urban development all around the county. In the 1970s, Hahn looked to the Southeast, perhaps Atlanta needs to look to the West.

Both cities suffered the same racial and class divisions that sapped public support for rail and twisted the lines into less effective routes. But I’m struck by the neighborhood opposition to development along the rail lines in both places, particularly based on a fear of gentrification.

In order for light rail to work, in terms of generating sufficient ridership to avoid becoming a huge economic liability for local transit systems, we need the lines to become growth inducing around the stations. That’s really the whole point of a rail line. Yet if we allow neighborhoods to prevent that growth, based on fears of displacement, traffic, lack of parking, and changing the character of the place, then we’ve negated the whole point of rail to begin with.

Certainly the lack of housing affordability and gentrification are reasonable concerns. But they shouldn’t be used as excuses to stop all development. Rather, that development should include a range of affordable housing, and project proponents should do their best to preserve local character.

Otherwise, we’ll end up with more sad rail histories, as we unfortunately see too much of in both Atlanta and Los Angeles.

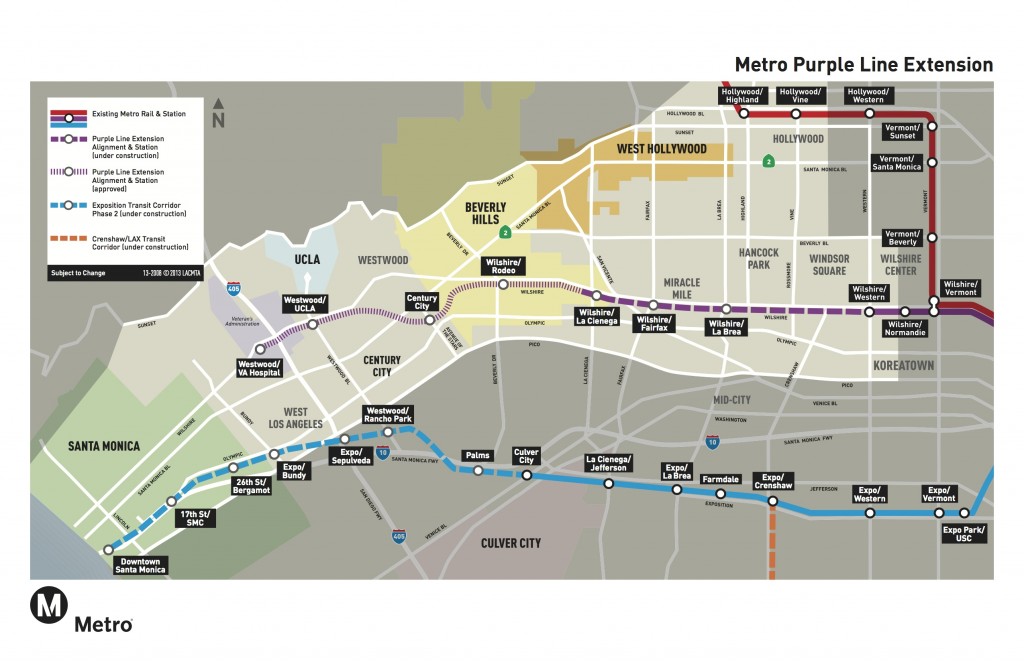

If LA were only to build one rail line, it should have been down Wilshire Boulevard. The corridor represents the most densely populated route west of the Mississippi River. So of course it will take almost 30 years since ground was first broken for Metro Rail before it starts to really serve that area. Today the federal government and Metro announced a $1.25B federal grant and $856M loan for the Wilshire “Purple Line” subway extension to go 3.9 miles, from its current terminus at Western, to La Cienega (dotted purple line in the map below):

It’s worth celebrating this announcement, because it’s a long time coming. It took a ridiculous amount of time to get here, and it’s worth remembering the highlights of the long battle:

- 1964: The Southern California Rapid Transit District was formed in Los Angeles in part to raise money to build a subway down Wilshire.

- 1968: Sales tax ballot initiative to pay for LA rail fails.

- 1973: Tom Bradley elected mayor on a pro-subway platform, the centerpiece of his campaign.

- 1974: Bradley’s sales tax measure fails.

Rep. Waxman, not ashamed to take credit this morning for the project he tried to kill and effectively delayed two decades. Supervisor Yaroslavsky, also pictured, supported Waxman’s ban while on the city council at the time.

- 1976: Another sales tax measure fails, this time from Supervisor Baxter Ward. But the Ford Administration grants some money to LA to begin studying rail.

- 1980: Proposition A, which dedicates some new sales tax money for rail, passes.

- 1985: Methane gas explosion on Fairfax Avenue gives Rep. Waxman an excuse to kill the subway in his district, which includes the key parts of the Wilshire corridor.

- 1986: LA rail officials negotiate a compromise with Waxman to keep the subway alive but out of his district. A ban on tunneling down Wilshire past Western Avenue is now federal law. Groundbreaking is held on the first 4.1 mile segment.

- 1990: Another half-cent sales tax measure passes.

- 1993: The first subway segment opens.

- 2000: The final 18.6 miles of the subway opens to North Hollywood.

- 2007: After two decades of lobbying, local leaders (and fed-up constituents) finally convince Waxman to relent on his tunneling ban, which was never rooted in legitimate engineering concerns over safety.

- 2008: Over 2/3rds of Angelenos vote for a sales tax measure to fund more rail (and other transportation improvements). The “Subway to the Sea” is a big part of the selling.

- 2012: Move LA and other transit leaders convince the federal government to include a low-cost loan program for projects like rail in LA with a dedicated revenue source (the sales tax). $856M in loans will now help this phase of the subway get built.

My book Railtown chronicles this history in more depth, but this is a snapshot. Of course, it doesn’t convey the decades of frustration, traffic, and misery that the lack of rail on this corridor has caused. It also doesn’t fully credit all the people who have played their part to make the subway happen. But at least it provides a sense of how long it can take to get good public policy right and hopefully an appreciation for how long this moment was in the making.

Journalist and podcaster Colin Marshall sat down with me for an hour last month to talk L.A. Metro Rail and Railtown for his “Notebook on Cities and Culture.” You can listen to the full podcast here. We covered Roger Rabbit, the influence of South American cities on LA, the too-short platforms on the Red Line subway, and the prospects for the future of the system, among other topics.

The New York Times ran an article today discussing the challenges of bringing rail transit to Los Angeles International Airport (good ol’ LAX), and it features a quote from me about I why I think rail to the airport is more of a psychological victory than a ridership victory. Without further explanation, this quote may be confusing or controversial, so let me clarify.

Generally speaking, rail to airports is not the most desired mode of choice for travelers. If you’re lugging suitcases, and even worse if you’re traveling with small children, rail is logistically challenging and often quite stressful, especially before a big air trip. (Unfortunately I know this from experience, having traveled with all three of my young kids on long BART rides to SFO or via AirBART to Oakland.) It’s often cheaper, faster, and easier to drive and park at an economy, off-site lot.Meanwhile, wealthy travelers often prefer to take expensive cabs or luxury cars to the airport, and many other travelers have friends who can give them rides. In addition, super-shuttles are popular, as are some inexpensive bus connections (AC Transit to Oakland for example or the Santa Monica Big Blue or Culver City bus to LAX).

So right off the bat, rail to the airport is only going to appeal to a relatively small subset of passengers — probably the relatively less-affluent solo passengers.

Second, and more specific to Los Angeles, most travelers’ destinations and origins are so spread out across the metropolitan region that the likelihood of living, working, or recreating near an existing rail station to connect to LAX is not huge. Even worse, the spread-out nature of the urbanized city means that even if you did live, work, or recreate near rail, you would likely have to transfer a number of times to get to LAX, resulting in a trip that could often take hours and be fairly expensive, at least under the current fare structure. For example, if you lived in Pasadena, you would take the Gold Line to the Red Line to the Blue Line to the Green Line, which I’m guessing is about a two-hour trip.

By contrast, the flyaway shuttle from Union Station is cheap and convenient for those near or accessible to downtown LA. Travel modes like the shuttle are likely to get more usage than rail for far cheaper and without the big infrastructure build-out time and expense.

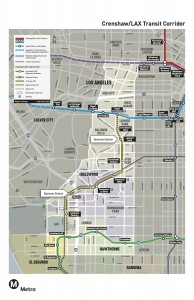

However, all is not doom and gloom when it comes to connecting LAX to rail. Here are some reasons for optimism: it will generate ridership, even if not the huge amount some might expect. In particular, airport employees will benefit as daily commuters. There will also be travelers for whom the Crenshaw line will provide quick service to their desired destinations (although that will probably be a small number of people). For example, in addition to destinations along the Crenshaw rail line, you could transfer from there to Santa Monica via a somewhat circuitous route or to downtown LA.

And more importantly, as Metro Rail gets fully built-out to reach major population, commercial and entertainment centers, the value of an airport connection will increase for both visitors and locals. The regional light rail connector through downtown will make possible a one-seat ride to Pasadena from LAX, eliminating the transfer mess I described above. A Crenshaw light rail connection to the Purple Line subway (not currently in the plans) could get travelers to Westwood, albeit circa 2037. And as I mention in the Times article, the psychological “branding” or image boost from rail to the airport will get Angelenos and visitors from around the world used to a new idea of an LA that is oriented around rail. More people will be curious about the system and may decide to ride it.

All good things.

But the point of my quote and perspective here is that rail enthusiasts should not overstate the importance of connecting the airport. It will be a slow, inconvenient journey for most people. Rather, advocates should focus on connecting high-density areas by rail and getting more high-density projects built around existing rail stations. Those advancements will benefit more people over the long-term than a rail-to-LAX project.

Today the Los Angeles Times is running an op-ed I wrote on the need to better integrate land use patterns into the region’s rail transit system. When I first started writing Railtown, I was a rail transit enthusiast who thought that the region was crazy for not building more of it. If I could have written an op-ed back then, I would have simply extolled the virtues of rail to get the public to support building more of it.

But as I researched the history and issues involved, it became clear that rail as a solution to LA’s problems was not the silver bullet I thought. Rail is expensive and complicated to build. More importantly, LA is a decentralized city with people going in every direction at all times of day. There’s very little order or centralization of jobs and housing, and it all takes place over a huge land mass. Not necessarily a great recipe for efficient rail service (although parts of LA are more than fit for rail, given their density).

So this op-ed is an attempt to recognize that complicated reality. The solution, if Angelenos want to make the most of their rail investment, is to make a better effort to channel future growth and development along the rail lines. If that doesn’t happen, rail will have failed to reshape the city and help overcome its traffic and quality-of-life challenges that plague so much of the region. Hopefully this op-ed will spark a debate about how best to make that happen.

The same blogger from the “My Book, The Movie” website also has a site dedicated to the belief that you can learn everything you need to know about a book by reading page 99. So I applied this test to Railtown, and here is the result. The opener:

Page 99 provides a decent snapshot of Railtown, my book on the history of the modern Los Angeles rail system. Actually, (spoiler alert) it provides a real-life snapshot of local leaders celebrating the groundbreaking of the subway portion of the system in 1986. That picture takes up half the page, making my job here easier.

Overall, just looking at page 99 is not a bad way to get a sense of the book, and it certainly gave me an opportunity to summarize the main points in an interesting way.