Today California inaugurates a new governor, Gavin Newsom, and says goodbye to four-term governor Jerry Brown. Governor Brown made climate change a central issue in his last two terms. Here are (to my mind) his top achievements on this issue:

Today California inaugurates a new governor, Gavin Newsom, and says goodbye to four-term governor Jerry Brown. Governor Brown made climate change a central issue in his last two terms. Here are (to my mind) his top achievements on this issue:

- Setting and signing clean energy goals: Some may take it for granted now, but when Governor Brown came into office, solar panel prices were almost 80% higher than they are today. By setting goals like 50% renewable energy by 2030 and now 100% carbon-free electricity by 2045, and then signing legislation to codify them, Governor Brown helped boost a global market for clean power that has dramatically reduced prices and helped California achieve its 2020 climate goals four years early. The progress also enabled countries and states around the world to take advantage of lower-cost renewable energy.

- Bolstering a low-level carbon tax through cap-and-trade: Governor Schwarzenegger originally launched the state’s cap-and-trade program before Gov. Brown took office, but Brown seized the mantle and put his political capital behind extending it through 2030 with a two-thirds legislative vote. While the program has its flaws, its minimum price floor guarantees something that approximates a low-level carbon tax, which produces billions of dollars for climate investments, from weatherization to high speed rail. It also strengthened the state’s image as a global climate leader in time for the 2015 Paris accord.

- Forging global climate cooperation: Gov. Brown’s senior advisor Ken Alex hatched the idea in early 2015 of a global pact of subnationals (cities and states) that wanted to take more ambitious action on climate change than their national governments. The movement took off, with California and the German state of Baden-Württemberg in the lead as founding members. Today it boasts a coalition of 220 governments who represent over 1.3 billion people and 43% of the global economy. It successfully pushed international climate negotiators to take stronger action on climate in 2015 and continues to be an important political and problem-solving force for climate on the world stage.

- Boosting zero-emission transportation: Much like renewable energy, zero-emission vehicles like battery electrics were very expensive when Governor Brown took office. But thanks in part to his leadership to boost incentives and mandates for these vehicles and the batteries that supply them, as well as the charging infrastructure to fuel them, battery prices have plummeted since he took office. This technological advancement has enabled longer-range, more affordable electric vehicles like the Chevy Bolt EV and Tesla Model 3. California is now home to roughly 50% of the plug-in electric vehicles nationwide, with home-state Tesla selling the majority of those vehicles in 2018. Progress on this technology is crucial, as climate policy will fail if we don’t reduce emissions from the transportation sector more generally.

- Setting long-term carbon neutrality goals: Governor Brown’s 2018 executive order calls for California to achieve carbon neutrality by 2045. It’s a bold goal that the legislature may soon codify, and it’s needed according to climate science. What it means is that the state will seek to offset whatever emissions it can’t reduce by 2045, possibly through technologies or practices that drawdown carbon from the atmosphere and sequester it in (or on) the ground. That type of technology will be an important next phase for climate action, as we seek to repair the damage done from historic emissions.

- Improving climate communication: Governor Brown never shied away from discussing climate change and made it a point to tell audiences about the dire threat and changes required to address it. At a time when political media generally stays away from climate coverage, Brown forced the issue to educate the public about the need for action. The most recent highlight was the September 2018 Global Climate Action Summit in San Francisco, which attracted major celebrities, activists, world leaders and media coverage for the issue.

Yet with all of these successes, Governor Brown leaves with one giant piece of unfinished business on climate change: achieving climate-friendly land use. In short, the governor was unable to ensure that most new housing and other real estate development in the state happen in the most climate-friendly locations (near transit and in existing urbanized areas) and types (i.e. multifamily, compact development). As a result, driving miles in the state are way up, as are emissions from transportation.

To be sure, the governor signed some helpful (though small-bore) legislation to address the challenge, and he achieved some reforms to the environmental review process that can hold up meritorious projects. But it was ultimately not nearly enough. It will therefore be up to the next governor and legislature to chip away at the local control that has has stymied this climate imperative. Increased sprawl and driving miles will otherwise undermine our emission reductions in other sectors.

On balance though, it’s hard to imagine California (or the world) having a more effective, focused and sincere advocate for action on climate change. For that reason, Governor Brown will be missed, though I look forward to seeing what he will accomplish out of office as a private citizen. He has left some big shoes for Gavin Newsom to fill — and a path forward on climate change for the rest of us to follow.

Last month at the Global Climate Action Summit in San Francisco, California Governor Jerry Brown made headlines announcing the launch of his “own damn satellite” to monitor climate pollution. The idea is not far-fetched, as a Montreal company has already launched satellites to detect methane leaks.

Last month at the Global Climate Action Summit in San Francisco, California Governor Jerry Brown made headlines announcing the launch of his “own damn satellite” to monitor climate pollution. The idea is not far-fetched, as a Montreal company has already launched satellites to detect methane leaks.

California’s satellite launch could be revolutionary for combating climate change, as it could greatly simplify the monitoring and enforcement challenge, saving money in the process and in turn allowing developing world countries to be more effective at reducing their emissions.

As E&E News reported [pay-walled]:

California’s aim is to launch the probe by the end of 2021, though state officials said a number of key details have yet to be finalized — notably funding for the project.

One big question is how much it will cost. The state has not released an estimate. Another is who is going to pay for it.

The governor’s office wants to rely on private donors and philanthropists to foot the bill, rather than taxpayers, and one Brown aide said California has yet to line up the necessary rainmakers.

But “our discussions with interested parties have been very, very positive,” Ken Alex, one of the governor’s senior advisers, said in a phone interview.

Brown will likely tap San Francisco-based Planet Labs Inc., founded in 2010 by three former NASA scientists and with Google as an equity stakeholder, to build it.

The upside is multi-fold. Specifically, the satellite could:

- Pinpoint hard-to-detect emissions from sources like landfills and fossil fuel wells, giving policy makers a more accurate way to assess where resources or policies are needed to reduce these emissions;

- Catch polluters in the act of misreporting their emissions, making enforcement easier; and

- Reduce the costs and lack of transparency in monitoring emissions, as the present methods are often opaque (in the name of protecting industry trade secrets) and burdensome.

And for countries and states less wealthy than California, the relatively low-cost satellite also means they won’t have an excuse not to invest in data collection on carbon pollution, if not mitigation measures, too.

All in all, it was a fitting — and potentially meaningful — end to the summit and to the near-close of Governor Brown’s term in office helping California fight climate change.

Yesterday was a big day of celebration for climate advocates in California. AB 32 (Nunez), the state’s signature greenhouse gas reduction bill, was signed in 2006 — ten years ago to the day. It requires California to reduce emissions to 1990 levels by 2020.

The day was marked by a celebration at Sacramento’s California Museum, sponsored by the USC Schwarzenegger Institute. The “Governator” spoke, as did current Governor Jerry Brown, CARB chair Mary Nichols, Sen. Fran Pavley, Sen. Kevin De Leon, and former Assembly speaker Fabian Nunez.

You can watch the full video above, but some highlights involved a vigorous defense of California’s economic growth since AB 32 passed. Speakers noted that the state has just surpassed the United Kingdom as the world’s fifth largest economy and that California’s GDP of 4.2% in 2015 was twice the national GDP of 2%. So claims that AB 32 would tank the economy have been largely put to rest.

Still, there’s reason to be cautious about bragging too soon. The full force of our emissions reduction efforts has not been felt on our economy, other than some changes such as with fuels, more renewables, and the beginnings of an electric vehicle market. The 2020-2030 time frame will involve much more dramatic changes to our energy system and economy if we hope to achieve the targets.

It was also entertaining to watch Governor Schwarzenegger when Gov. Brown reminded the audience that the politically controversial Delta tunnels and high speed rail projects were launched on his watch. And Gov. Brown emphasized that we’re playing “Russian roulette” with the physics of extreme weather if we don’t act now.

So while yesterday was a day to celebrate, much work remains to be done. Fortunately, as the political showing yesterday indicates, we have powerful momentum and support to carry out the task.

Governor Brown angered a lot of people in the local government and environmental communities when he proposed “by-right” state approval of multifamily housing consistent with existing local zoning in his last budget. Negotiations are set to conclude tomorrow, based on the budget deal.

Governor Brown angered a lot of people in the local government and environmental communities when he proposed “by-right” state approval of multifamily housing consistent with existing local zoning in his last budget. Negotiations are set to conclude tomorrow, based on the budget deal.

Carol Galante, a colleague at UC Berkeley, penned a recent op-ed in the Sacramento Bee in support:

The state’s entitlement process has become unnecessarily complicated and cumbersome. The permitting process for new development in California coastal communities takes over 30 percent longer than in the average American city.Not surprisingly, this greatly increases the costs of development: in the Bay Area, each additional layer of independent review is associated with a 4 percent increase in a jurisdiction’s home prices.

Other states, like Massachusetts, have tackled the problem in a similar fashion to Brown’s, showing that it doesn’t need to be this way. California’s “by right” proposal would allow new attached housing – consistent with existing general plans and zoning rules, in urban infill locations with at least a portion dedicated for families at the lower end of the income scale – to be deemed good to go. This proposal would put an end to lengthy process hearings and stall tactics often employed by special interests or “NIMBY” opponents.

I’ve previously argued that this kind of approach is needed, but I remain concerned that the proposal could open the door to sprawl approvals. As the Planning and Conservation League noted in their letter on the proposal:

The proposal’s site requirements allow benefits to be accessed by developments outside urbanized areas. Section 65913.3 (b) (3) requires the site to be adjacent to developed parcels, but says nothing about the characteristics of the surrounding area. Two lone houses in an otherwise-undeveloped area could meet the language’s standard. This would promote sprawl, which requires long-term maintenance of roads, highways and other infrastructure that neither the state nor local governments can afford.

The easiest solution would be to limit the by-right eligibility to projects in “transit priority areas” or areas within 1/2 mile of a major transit stop. In addition, the projects could have a “vehicle miles traveled” (VMT) performance standard to ensure they actually encourage transit use.

Because while we need more housing in many parts of California, we don’t need more sprawl. And that one possibility is an unfortunate aspect of an otherwise necessary approach to addressing the housing crisis in the state.

Governor Brown’s proposal in his new budget to make certain housing developments eligible to be approved by the state “by right” has riled up not just local governments — who stand to lose discretionary approval over these projects — but some labor and environmental groups as well.

It’s pretty obvious why these groups are upset: the by-right state approval means they lose their leverage over projects under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), which can trigger lengthy local environmental review for discretionary approvals. And the governor’s proposal, as currently written, lacks safeguards to ensure that only environmentally beneficial projects are eligible for state approval.

Yet local resistance to new housing is a problem well beyond CEQA, and its cumulative effect — through restrictive local zoning, discretionary rejection of new housing, and citizen petitions and lobbying — has created a massive housing shortage in the state’s big cities. The inevitable result is high housing costs squeezing middle-income earners, with displacement and gentrification pushing out low-income earners. It’s becoming a national drag on our economy, while pushing new development out to the exurbs and over open space and farmland.

So in principle, state approval of certain housing projects is justified. But it needs to be the right kind of housing development, consistent with existing local plans. A relatively straightforward condition on these projects to be eligible is that they are located within a half-mile of a major transit stop and meet certain vehicle miles traveled (VMT) and greenhouse gas emission profiles. That would ensure environmental performance and that the projects do not contribute to sprawl.

The basic formula would be: 1/2 mile + VMT + GHG = by-right approval.

Of course, you’d probably have to layer in an affordable housing requirement as well to achieve political consensus. But increasing supply today will go a long way to stabilizing prices and therefore minimizing displacement, as well as creating the housing stock that will one day be affordable to low-income earners. And in the meantime, we can ensure that these new projects contain affordable units.

And for the labor groups, these multi-unit housing developments typically require higher-paying, high-skilled jobs that pay better than sprawl construction.

It would be a win-win, if our political leaders and advocates can arrive at compromise.

With his “May revise” budget [PDF], California governor Jerry Brown cuts to the heart of why housing is so expensive in coastal California:

With his “May revise” budget [PDF], California governor Jerry Brown cuts to the heart of why housing is so expensive in coastal California:

Local land use decisions surrounding housing production have contributed to low inventories — even though demand has steadily increased. Local land use permitting and review processes have lengthened the approval process and increased production costs. Ultimately, the state’s housing affordability will improve only with new approaches that increase the housing supply and reduce its cost. The Legislature is currently considering a number of these approaches. The May Revision proposes additional legislation requiring ministerial “by right” land use entitlements for multifamily infill housing developments that include affordable housing. This would help constrain development costs, improve the pace of housing production, and encourage an increase in housing supply. It is counterproductive to continue providing funding for affordable housing under a system that slows down approvals in areas already vetted and zoned for housing.

This approach has been tried this year by the legislature. Assemblyman Richard Bloom (D-Santa Monica) authored AB 2522, which would have provided exactly this kind of “by right” state approval for local affordable projects near transit. But my understanding is that the League of California Cities has killed it, and the bill’s status page indicates its committee hearing last month was canceled at the “request of the author.”

I’m pleased to see the governor take this issue on, but given the knotty politics and power of the local government lobby, I’m not optimistic. Local governments will never be happy if proponents of controversial infill projects can simply go right to the state for permitting approval.

But the status quo has not worked: every local jurisdiction has an incentive to say “no” to these projects in order to appease vocal residents in opposition. The overall result is that not enough housing gets built region-wide, leading to shortages, high housing costs, a squeezed middle class, displacement, gentrification, and a lack of older housing stock that is affordable for low-income residents.

While we see what happens with this proposal, advocates can meanwhile focus on solutions that the local government lobby can get behind, like developing new financing tools that local governments can use to pay for infill infrastructure and other costs. Because if the governor’s proposal doesn’t fly, we should still try to make progress on this issue where we can.

Big news in the climate world yesterday as California Governor Jerry Brown announced ambitious 2030 targets for greenhouse gas emissions for the state:

The target, contained in an executive order and expected to be folded into pending legislation, seeks to reduce emissions in California 40 percent below 1990 levels by 2030.

The goal is in line with one adopted by the European Union last year, and proponents characterized it as the most aggressive in North America.

“With this order, California sets a very high bar for itself and other states and nations, but it’s one that must be reached – for this generation and generations to come,” Brown said in a prepared statement.

California is well on pace to meet our 2020 goals set forth by AB 32. But admittedly, we’ve had some winds at our back. The recession significantly cut energy demand and also seems to have reduced driving miles, although there could be multiple factors there. Cheap natural gas has also helped.

But make no mistake, California has encouraged significant progress on renewables and electric vehicle deployment, and is starting to make strides on energy storage as well. These will be critical technologies to meeting the governor’s 2030 goals. But the other big challenge will be the less sexy energy efficiency efforts, which so far the state has made only moderate progress on.

Still, with these goals, the path is now laid out for businesses, regulators and the public to follow. And California will provide a strong example for other states and countries by showing how to decarbonize the economy without hurting economic growth.

Jerry Brown was inaugurated today for his record fourth term as governor of California, and his address offered refreshing specifics on his environmental and climate goals:

In fact, we are well on our way to meeting our AB 32 goal of reducing carbon pollution and limiting the emissions of heat-trapping gases to 431 million tons by 2020. But now, it is time to establish our next set of objectives for 2030 and beyond.

Toward that end, I propose three ambitious goals to be accomplished within the next 15 years:

1. Increase from one-third to 50 percent our electricity derived from renewable sources;

2. Reduce today’s petroleum use in cars and trucks by up to 50 percent;

3. Double the efficiency of existing buildings and make heating fuels cleaner.

The 50% renewable standard by 2030 is the most striking of these recommendations, putting California on pace to lead the nation in renewable deployment (with Hawaii as a possible rival, given that state’s expressed goal of 65% renewables by 2030). As Berkeley and UCLA Law discussed in the November 2013 report Rewable Energy Beyond 2020: Next Steps for California, such a standard should be accompanied by a policy to ensure actual greenhouse gas reductions from the power sector. Otherwise, an increase in renewables could be offset by an increase in fossil fuel-based power, which might be needed to balance the intermittent renewables when the sun isn’t shining and the wind isn’t blowing — but demand remains high.

Governor Brown seems to acknowledge that risk when he called for specific measures to help ensure proper integration of these renewable power sources:

I envision a wide range of initiatives: more distributed power, expanded rooftop solar, micro-grids, an energy imbalance market, battery storage, the full integration of information technology and electrical distribution and millions of electric and low-carbon vehicles. How we achieve these goals and at what pace will take great thought and imagination mixed with pragmatic caution. It will require enormous innovation, research and investment. And we will need active collaboration at every stage with our scientists, engineers, entrepreneurs, businesses and officials at all levels.

Battery and other energy storage technologies (also detailed in this 2010 Power of Energy Storage report) are vital to balancing renewables on the grid by storing surplus renewable power for later dispatch. California is making great progress on deployment so far. And an energy imbalance market, linking renewable sources across the Western United States, as well as “demand response” technologies that encourage energy usage during times of peak renewables, will also help decrease greenhouse gases from the power sector as well as increase grid reliability and decrease costs.

Finally, the governor’s electric vehicle and energy efficiency goals represent the two other critical pieces in the effort to reduce greenhouse gas emissions without having to return to the stone age. After all, it’s not enough just to clean our electricity sector — we need to electrify our transportation and be much more efficient with the energy we do use. All told, Governor Brown is reinforcing through policy the critical initiatives we need to grow the economy without overheating the planet beyond repair.

The next stage will be the administration’s goal for greenhouse gas reduction legislation for 2030 — a sequel to the AB 32 2020 goals. The governor set a timetable of March 2015 to unveil those targets, so we’ll stay tuned for that next big speech on the environment.

This morning in Sacramento, former California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger journeyed back to his old stomping ground to highlight the state’s successes fighting climate change. He joined current governor Jerry Brown and a host of climate experts and business leaders to make the case for the 2015 Paris climate talks that California’s example can be replicated at an international scale.

But for all the dignitaries, politicians, and experts, there was actually very little said about the specific policies that seem to work in California. Nor was there discussion of any of the clean tech businesses that are leading the way to reduce greenhouse gases. Instead, it was a largely symbolic, self-congratulatory event, sprinkled with some useful facts and motivational talks.

First up, the former governator ran through the history of California’s climate fight since he took office, talking about how big business fought the climate agenda at every turn, claiming doom and gloom and seeking to overturn AB 32, the climate law, with a 2010 ballot initiative. “But Californians terminated it” at the polls, he quipped, “saying ‘hasta la vista baby’ to the oil companies.’ Later, Governor Brown echoed this sentiment about big businesses always crying wolf about environmental regulations, noting that Henry Ford himself even came to California to lobby against fuel efficiency standards in the 1970s.

Climate scientists followed, including UC Berkeley’s Dam Kammen and the Pacific Institute’s Peter Gleick. Gleick brought home the impacts of climate change on California when he noted that $100 billion worth of 2000-era buildings are threatened by sea level rise, which could displace 480,000 people living on the coastline and jeopardizing 10,000 megawatts worth of power plants, among other calamities.

A business panel followed, although not one with any of the leading clean technology companies. Former EPA head and now Apple Computers Executive Lisa Jackson described the “fun” and “opportunities” of fighting climate change at Apple with their net-zero data centers. Michael Britt of UPS acknowledged that the company is not afraid of higher gas prices under AB 32 and described internal combustion engines as an unsustainable “bridge” to cleaner technologies. The company will deploy 17 fuel cell trucks in the coming months at one-third the maintenance costs of traditional engines.

State Senate President-to-be Kevin De Leon then joined a panel where he discussed his efforts to include low-income Californians in the fight against climate change. His one million constituents live in a district criss-crossed by seven major freeways, and with 40% of the goods in the United States shipped through there, “a little girl’s lungs subsidize” the cheap purchases we make. Moderator Terry Tamminen noted that kids near the port in Los Angeles/Long Beach lose one percent of their lung capacity on average each year. De Leon felt that government should encourage more private investment in clean technologies, because “there isn’t enough public money” to do the job. He specifically cited the need for a stronger state infrastructure bank, one of the few specific policy needs discussed today.

Finally the current governor spoke, bringing laughs when he said that California’s environmental fight began with a Republican actor turned governor — Ronald Reagan of course, not Schwarzenegger. Brown’s point was that under Reagan and President Nixon, California secured a waiver in the federal Clean Air Act to go beyond federal standards, paving the way for California’s continued leadership on environmental issues. Ultimately, Brown described how we need to look to scientists and entrepreneurs to save us, while government can provide them the incentives.

Missing in the discussion today was exactly that: the businesses and the incentives. For example, no mention of Tesla, the California-bred company that is probably doing the most right now to bring down the costs of the technologies needed to clean our economy. And only a brief mention of the solar rooftop incentives in California and cap-and-trade, with nothing about California’s landmark energy storage law.

If California is going to make a case to the world about the policies needed to reduce carbon, we’ll need to do a better job than what our leaders did today. We can certainly brag about the broad goals California has set, and we should do so. But unless we can demonstrate the specific business and health advantages that the California program has brought, it will all seem pie-and-the-sky to outsiders.

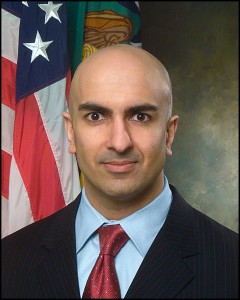

In last night’s California gubernatorial debate, Republican candidate Neel Kashkari proposed a major reform to the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), which requires environmental review of new projects. But rather than gutting CEQA completely, a la State-Senator-turned-Chevron-lobbyist Michael Rubio, Kashkari proposed to give all projects the same breaks that the Sacramento Kings received in last year’s SB 743 (Steinberg). As Kashkari explained:

When the Sacramento Kings were going to leave, and the NBA said we need a new arena…Governor Brown signed an expedited review, gave them a special deal… But instead of just giving it to those who are politically connected who can hire high-priced lobbyists, why don’t we actually adopt that new standard and make it available to everyone?

And from Kashkari’s website:

[A]ll projects that come under CEQA challenge should be afforded the same injunctive relief and expedited review process that the Sacramento arena warranted.

So what exactly did the Sacramento Kings get? As I described at the time:

SB 743 [gave] Sacramento Kings basketball arena proponents accelerated environmental review and immunity from injunctive relief unless the project is found to jeopardize public health, safety, or archaeological resources. In exchange for these benefits, the new stadium must meet strict environmental performance measures, including net-zero greenhouse gas emissions from passenger trips to the stadium, LEED Gold certification, and compliance with the sustainable land use plan for the region under SB 375. In short, basically the same performance standards required for $100 million projects under AB 900 (2011)

So the Sacramento Kings only received the injunctive relief and expedited review upon pledging to meet high environmental standards related to energy efficiency and greenhouse gas emissions. Somehow I don’t think that’s the standard Kashkari wants to apply to all businesses in California. First of all, it’s unworkable given the range of projects covered by CEQA (a transit line, for example, isn’t even eligible for LEED gold certification, which is limited to “buildings”). Secondly, it would ensure greater environmental protection, which Kashkari doesn’t seem to prioritize. Third, it would place a huge burden on the courts to expedite these projects, and Kashkari doesn’t seem likely to spend more money to boost their staffing to be able to handle the additional caseloads.

To echo the governor’s words last night, this “glib” proposal belies the true nature of the deal that the Kings received. Coupled with Kashkari’s plan to shift high speed rail bond funds to additional water storage projects (a move that would be illegal — not to mention a betrayal of the majority of voters who approved those funds in 2008 for high speed rail only), the candidate appears to be playing fast and loose with the facts, at least on environmental issues.