The race for zero emission vehicles has largely been between hydrogen fuel cell technology and batteries. Many analysts feel there really isn’t a competition, given the superiority of batteries for both environmental and economic impacts. A new study from Stanford underscores this reality:

The results were definitive.

“In terms of overall costs, we found that battery electric vehicles are better than fuel cell vehicles for reducing emissions,” Felgenhauer said. “The analysis showed that to be cost competitive, fuel cell vehicles would have to be priced much lower than battery vehicles. However, fuel cell vehicles are likely to be significantly more expensive than battery vehicles for the foreseeable future. Another supposed benefit of hydrogen – storing surplus solar energy – didn’t pan out in our analysis either. We found that in 2035, only a small amount of solar hydrogen storage would be used for heating and lighting buildings.”

Perhaps more significantly, Toyota — one of the few automakers that has gone all-in on hydrogen — appears to be retrenching in favor of batteries, according to Elektrek:

Now one of the most prominent proponents of hydrogen fuel cell cars, Toyota, is reportedly planning to mass produce battery-powered long-range electric cars by 2020.

The news comes as Toyota is having difficulties selling the Mirai, its hydrogen cars, in the US. Despite cutting the price on several occasions, with now a lease at only $350 (down from $500) in California, the Japanese automaker can’t find a market for the vehicle and only delivered 782 units since it started deliveries last year – and that’s including the state buying dozens of them for their own fleets to justify the millions of dollars spent on refuelling infrastructure.

And as Nikkei reports:

Eyeing a full-scale entry into the electric vehicle market, the Japanese automaker will create an in-house team for planning and development as soon as the new year. Toyota will seek cooperation from group companies to start production quickly.

Toyota aims to develop an EV that can run more than 300km on a single charge. The platform for models such as the Prius hybrid or Corolla sedan is being considered for use in building an electric sport utility vehicle.

This is definitely significant news, particularly given that it seems to be in response to stagnant fuel cell vehicle sales. Of course, we shouldn’t pit technologies like these against each other, as hydrogen could potentially have a role for zero-emission transportation like long-haul trucking that is less suited for batteries. But it’s also not great to spend a lot of public dollars on hydrogen fueling infrastructure that won’t be needed. Maybe this latest development signals a new future for investments in EVs, without the distraction of fuel cells.

There’s been a low-grade battle for the future of zero-emission vehicles in California. On one side are the well-known battery electric models, with companies like Tesla capturing the global imagination and state residents buying hundreds of thousands of vehicles to date.

On the other side are hydrogen fuel cell vehicles, capturing the imagination of…well, maybe a hundred buyers and a few state officials.

The problem is that the state is spending millions of dollars to subsidize both technologies, when many experts feel that hydrogen fuel cell vehicles will have very little role in the state’s transportation future.

Now Fred Lambert at Electrek observes that even the fuel-cell automakers are changing their tune:

I think we are witnessing the start of a new (but long overdue) trend this year. The few established automakers still pushing fuel cell hydrogen vehicles appear to be warming up to battery-powered electric vehicles instead. Honda, Toyota and Hyundai, arguably the automakers most stuck on hydrogen, all announced new electric vehicle programs in the past few weeks.

Toyota is working on a plug-in version of the Corolla. Hyundai is bringing its Ioniq electric platform to market by the end of the year and this morning, we reported on the Korea-based automaker developing a next generation battery-powered electric SUV.

Those two automakers are arguably the most entrenched in fuel cell technology with the Toyota Mirai, the Hyundai Tuscon Fuel Cell, and billions spent in investments between the two of them, but the most telling news is that Honda, another fuel cell believer, is planning to launch a battery-powered version of the Clarity, a car it actually developed for its fuel cell program.

Lambert notes the gaping inefficiencies of fuel-cell vehicles compared to battery electrics (which are almost three times more efficient, when accounting for the energy in versus the energy out), plus the greater complexity of the manufacturing/fuel supply process with fuel cells.

The only advantage hydrogen offers over battery electrics is refueling time. But as batteries eventually move to up to the 600-mile range in the coming decades, and as fast-charging technology improves, this benefit will diminish. Meanwhile, battery electrics have the contrary advantage of being able to fuel in your home and anywhere with an outlet, versus the need for the gas station model of hydrogen fueling.

To my mind, the only true benefit of hydrogen is for long-haul trucking (although biodiesel and other biofuels may be just as well-suited), and possibly as a form of energy storage, assuming the hydrogen is made from surplus renewables.

But I’m skeptical that automakers will truly abandon their fuel cell plans so quickly. My guess is it will be another five years or more before they truly get the message from the market.

Toyota announced its new fuel cell vehicle, the Mirai. Available only in California, it has a range of up to 300 miles at $57,500 (not including rebates and tax credits), which also includes free hydrogen fueling for three years. The advantage? It can refuel in 5 minutes, compared to an hour or way more in a traditional battery electric vehicle.

The disadvantages? Well, if you like looks and horsepower, this vehicle won’t do it for you. One website review called it “crazy ugly” and noted it takes 9 seconds to accelerate to 62 miles per hour (compared to 4.1 seconds for the Tesla Model S).

The real disadvantage? The fueling infrastructure isn’t there. While battery electric drivers may complain about the lack of charging stations, at least electricity is ubiquitous and basically cheap. But with hydrogen, we need a whole new, expensive, and energy-intensive infrastructure to produce and dispatch the hydrogen.

Here’s Toyota’s response:

Research at the University of California Irvine’s Advanced Power and Energy Program (APEP) has found that 68 stations, located at the proper sites, could handle a FCV population of at least 10,000 vehicles. Those stations are on their way to becoming a reality. By the end of 2015, 3 of California’s 9 active hydrogen stations and 17 newly-constructed stations are scheduled to be opened to the general public, with 28 additional stations set to come online by the end of 2016, bringing the near-term total to 48 stations.

Nineteen of those 48 stations will be built by FirstElement Fuels, supported by a $7.3 million loan from Toyota. The company has also announced additional efforts to develop infrastructure in the country’s Northeast region. In 2016, Air Liquide, in collaboration with Toyota, is targeting construction of 12 stations in five states – New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island.

Personally, I think the expense and energy needs for the fuel disqualifies hydrogen fuel cells as a viable technology, at least for passenger vehicles. However, given that we need to electrify pretty much all of our transportation to meet our long-term greenhouse gas reduction goals, I could see hydrogen being useful (and maybe necessary) for heavy-duty shipping, as batteries may not be able to provide the power necessary.

In any event, we can see how Toyota and other fuel cell-committed companies like Honda do with their technologies. But from a public policy standpoint, we should not be subsidizing the fueling infrastructure for vehicles like the Mirai.

I posted a few weeks ago about the hydrogen fuel cell versus battery electric vehicle debate, citing alternative fuel expert Joe Romm’s evidence. Romm is back at it, highlighting the high costs and lack of environment benefits of hydrogen fuel cells:

The biggest problem hydrogen fuel cell vehicles face is that they deliver no obvious major consumer (or societal/environmental) benefit compared to the competition, but have a bunch of obvious consumer defects. These defects include high first cost, high fueling cost (compared to both gasoline and electricity), lack of fueling stations and lack of a nationwide fuel-delivery infrastructure — especially for renewable hydrogen.

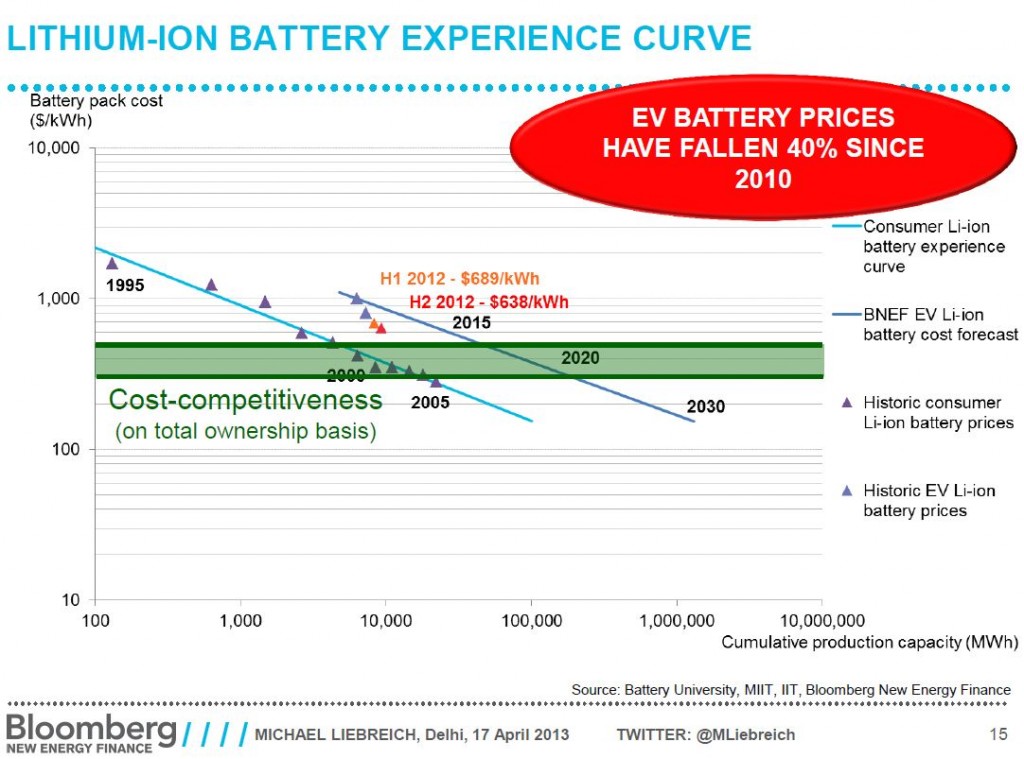

Romm also describes the significant price decreases seen over the past few years in lithium ion batteries:

[M]assive amounts of money were poured into improving batteries and related components, not just by governments, car makers and clean energy venture capitalists, but also by portable device and phone manufacturers who wanted to improve performance while cutting costs. The results in the case of batteries have been impressive:

Between these highly encouraging battery cost reductions and the corresponding steep mountain to climb on hydrogen fuel cells, I continue to wonder why California just invested $50 million in this dubious technology.