The law firm of Holland & Knight has made waves over the past few years attempting to quantify how bad CEQA has been for pro-environment projects like infill and renewable energy. Their allies in the business community and Sacramento, along with unwitting media outlets, have trumpeted the results.

They are now out with a new “update” [PDF] on their flawed 2015 study that purports to show how CEQA has been overwhelmingly used against infill in the Southern California region.

But the problem, as I and my colleague Sean Hecht at UCLA Law have noted, is that they misleadingly chose a definition of “infill” in that 2015 study (and again in this update) that is so broad that it over-represents how often infill projects are subject to CEQA suits, out of all CEQA litigation in a given time frame.

Misleading may be a strong word, but how else can you explain it when they claim to be using a state-approved definition of infill that doesn’t in fact match their definition?

Here’s what they write:

In our [2015] statewide report, we called these “infill” locations, consistent with the infill definition used by the Governor’s Office of Planning & Research (OPR).

And here’s the definition they use:

[Projects] located entirely within the boundaries of existing cities or in unincorporated county locations that were surrounded by existing development.

Yet in their own footnote to OPR’s definition, we find the following from OPR:

“The term “infill development” refers to building within unused and underutilized lands within existing development patterns, typically but not exclusively in urban areas. Infill development is critical to accommodating growth and redesigning our cities to be environmentally and socially sustainable.”

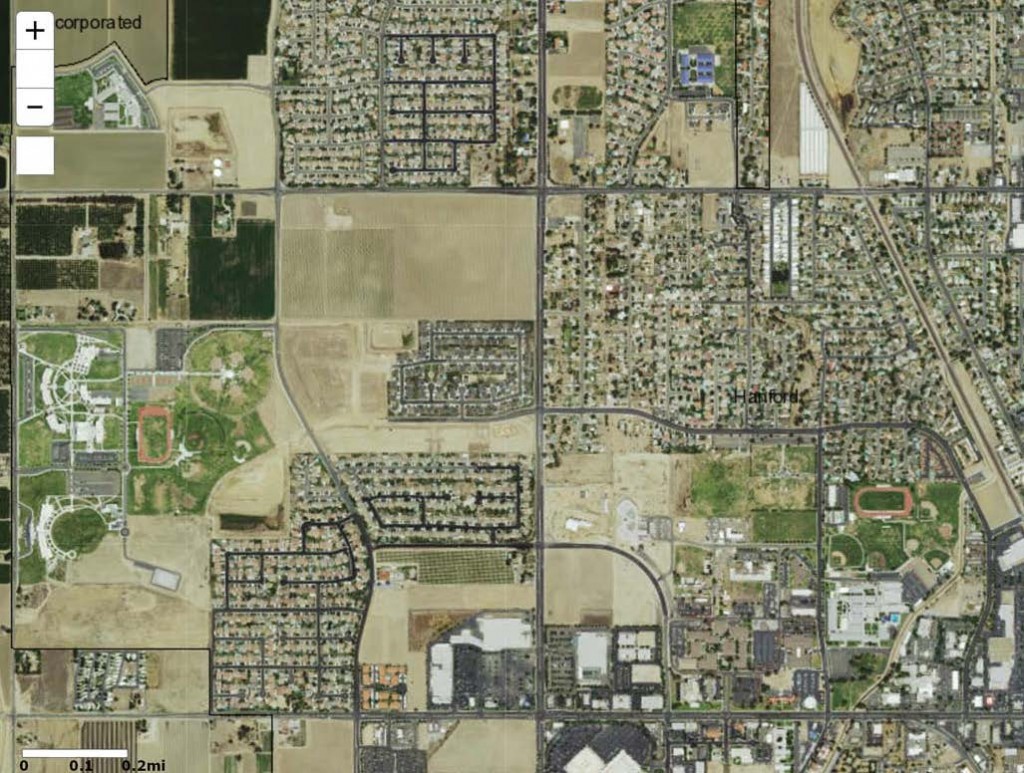

Notice any inconsistencies? Nowhere does OPR claim that any development within existing city boundaries should be considered infill. Yet that’s exactly what Holland & Knight claim their definition encompasses. By adding that geography to the definition, they get to call areas like in this random screenshot of Hanford “infill”:

If they really want to update their study, they need to stop claiming that they’re using a state-sanctioned definition of infill. Because they’re not.

Here’s another definition they could have used, that was added to CEQA by the legislature:

21061.3. Infill site means a site in an urbanized area that meets either of the following criteria:

(a) The site has not been previously developed for urban uses and both of the following apply:

(1) The site is immediately adjacent to parcels that are developed with qualified urban uses, or at least 75 percent of the perimeter of the site adjoins parcels that are developed with qualified urban uses, and the remaining 25 percent of the site adjoins parcels that have previously been developed for qualified urban uses.

(2) No parcel within the site has been created within the past 10 years unless the parcel was created as a result of the plan of a redevelopment agency.

(b) The site has been previously developed for qualified urban uses.

The report does go to some length to describe the challenges of defining infill for the purposes of a study like this one. Personally I favor a definition linked to proximity to major transit stops, coupled with the definition Deborah Salon formulated in 2014 for the California Air Resources Board [PDF] based on low-vehicle miles traveled (VMT) neighborhood types.

But by misrepresenting their definition of infill, Holland & Knight undermines the credibility of their report and the quality of the findings. If they issue any further “update” to it, I hope they finally correct that flaw.

Chip Johnson in today’s San Francisco Chronicle tackles the all-important question of the lack of housing in the Bay Area. He rightly focuses on the greed of those who seek to prevent new infill housing from being built.

But he goes awry in singling out the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) as the primary culprit. He cites the discredited Holland & Knight CEQA study as proving that infill projects suffer the most under CEQA, when that study defined the term so broadly that almost 90 percent of housing projects in the state are classified as “infill.” I wish he and others in the media would study up on this study before citing it, as it should not be used to inform policy going forward.

He then cites some CEQA reform measures that the study recommends, some of which I actually could support:

The study offered possible remedies: requiring anyone filing a new lawsuit under CEQA to state their environmental concerns, eliminating duplicate lawsuits for plans and projects that have already won approval, preserving the right of environmental review and public comment, and scaling back court-ordered invalidation of project approvals that harm health, destroy tribal resources or threaten the environment.

It doesn’t take a genius to figure out that if suburban sprawl is blocked for environmental concerns, and open lands are protected and urban in-fill is limited, it’s going to be very difficult to provide housing of any kind, except for the very wealthy.

I would favor eliminating duplicate lawsuits over plans and ensuing projects, which ultimately means strengthening the CEQA “tiering” provisions that allow projects to proceed by-right once they are consistent with an already-approved plan. And I would favor greater transparency about who is suing and the settlements they reach.

But the problem with this study (and this article) is that CEQA is not the only significant barrier to new infill development, which is mostly stopped by local zoning, lack of adequate infrastructure in infill areas, and perverse incentives caused by Proposition 13. Too often proposed CEQA “reforms” are really about benefiting sprawl, oil-and-gas, and other industrial projects, with infill used as a convenient, politically popular cover.

I’m afraid Mr. Johnson may have fallen into that trap by citing this issue and this study so prominently in his piece. Otherwise, I’m glad to see he’s taking on this issue.

We hear a lot about CEQA abuse, but maybe it’s time for a new term: “CEQA study abuse.”

As I blogged previously, the law firm Holland & Knight issued a report attempting to document how the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) undermines environmental goals. I certainly share the concern of many industry actors and their representatives at law firms like Holland & Knight that CEQA is sometimes counter-productively used against meritorious projects, particularly infill development. And that’s why I’ve supported reforms to the law that help environmentally beneficial projects, such as those that lower overall driving miles and are located near high-quality transit. SB 743 (Steinberg, 2013) is the perfect example of this approach.

But the Holland & Knight study, which tracked litigation records (notably leaving out other ways that CEQA affects project approvals, both good and bad) used an overly broad definition of infill that inflated the results. My UCLA Law colleague Sean Hecht exposed the flaw in this post.

But then Don Perata, former state senate president, came to Holland & Knight’s defense. Perata represents an organization called the “California Infill Builders Federation,” but his arguments support anything but infill. His post on the political site Fox & Hounds didn’t try to rebut Sean’s points but instead misrepresented them, as Sean described in his counter-response.

Bottom-line: the “Infill” Federation is apparently comfortable with a definition of infill that includes all projects located within the boundaries of every city in California, including some county locations. For a visual representation of what that means, here’s the map of incorporated California cities:

For a closer look, here’s incorporated Orange County, which essentially covers the entire jurisdiction not on a mountain or a military base:

For a closer look, here’s incorporated Orange County, which essentially covers the entire jurisdiction not on a mountain or a military base:

And even closer, here’s a supposedly “infill” area in incorporated Hanford in the San Joaquin Valley:

Most of these areas should fit no one’s definition of “infill,” and the report authors should correct that labeling in the study. Relaxing CEQA requirements in these outlying areas would only benefit sprawl and hurt efforts to promote infill-friendly policies.

Most of these areas should fit no one’s definition of “infill,” and the report authors should correct that labeling in the study. Relaxing CEQA requirements in these outlying areas would only benefit sprawl and hurt efforts to promote infill-friendly policies.

Furthermore, as Sean originally noted, this CEQA “study” should not be the basis of any policy making. I hope Sacramento decision-makers are paying attention, because this book should definitely not be judged by its cover.

The big law firm Holland & Knight has been on a crusade against California’s signature environmental law, the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), for a while now. I’ve had my tangles with partner Jennifer Hernandez there, who has issued some misleading studies to derail sensible CEQA reform.

Recently, the law firm tried to step up its game to issue a seemingly-comprehensive study of CEQA litigation to prove once and for all how the law is badly misused by NIMBYs and labor unions to stop badly needed projects. Among the chief conclusions, CEQA mostly targets infill projects, as well as transit and renewables.

The problem is, as my UCLA Law colleague Sean Hecht writes in a devastating takedown, the evidence doesn’t support their conclusions.

On infill, the study defines it as anything within incorporated city limits or adjacent to a development in unincorporated area — in other words an absurdly large geographical area that matches nobody’s definition of environmentally beneficial development. Hecht goes in for the kill:

Unsurprisingly, the definition includes projects that virtually no one would recognize as “infill” under any common definition. For example, this Wal-Mart in Milpitas appears to be classified as “infill,” along with several other Wal-Mart projects. So is Chandler Ranch, a new development in suburban Rolling Hills Estates that includes 114 single-family luxury homes plus a new golf course and clubhouse for the Rolling Hills Country Club. Moreover, some “infill” projects clearly do not provide benefits to their communities. The Bradley Landfill site, the subject of Comunidad en Accion v. Los Angeles City Council, is a waste management site in the middle of a poor Latino community. And another “infill” case, City of Irvine v. County of Orange, involved the expansion of a jail, partially on agricultural land, from 1200 inmates to 7,584 inmates. Many of the “infill” projects are industrial facilities, including asphalt and cement plants. The data presented just don’t support the idea that CEQA cases mostly target projects that support environmentally-sound development that is good for communities. The fact that projects challenged under CEQA are mostly located within the geographical boundaries of cities simply doesn’t prove anything.

On transit, Hecht found only a few lawsuits a year in the Holland & Knight dataset related to transit, including one that actually involved a paint and body industrial facility serving transit lines, rather than a transit project (whoops!).

On renewables, over the three-year study period, the report found just five solar projects and two wind projects that were challenged under CEQA. Hardly a damning amount, particularly given the questionable approval in the first place on one of the wind projects.

Hecht’s demo job of the report was badly needed and speaks to the problem of having ideologically motivated industry actors attempt a neutral “study” of something as hot-button as CEQA. In the future, I hope Holland & Knight attorneys stick to representing clients and leave the CEQA analysis to people who don’t have an axe to grind.

California’s Governor’s Office of Planning and Research (OPR) has been getting slammed for trying to implement sensible reform to benefit infill development. As I described back in August, the law firm of Holland & Knight issued a wrong-headed attack on OPR’s proposed new guidelines for the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). And a statewide business coalition also weighed in, parroting the Holland & Knight attacks. All because OPR, complying with a directive from SB 743 (Steinberg, 2013), is essentially exempting infill projects from transportation review under CEQA, while introducing a simpler vehicle miles traveled (VMT) analysis for sprawl projects.

So it was a nice opportunity for me to debate one of the Holland & Knight attorneys, Jennifer Hernandez, on this subject on Tuesday night at University of San Francisco School of Law. I participated in a four-person panel, with Michael Schwartz (lead transportation planner in San Francisco), Amanda Eaken (NRDC), and Jennifer and me, plus Adam Hofmann moderating.

We took turns making our case. Michael covered how the dysfunctional, status quo “level of service” standard of review works, as well as its negative effect on specific projects San Francisco, like the long-delayed bus rapid transit line down Van Ness. Amanda then made the pitch for VMT but expressed concern about OPR’s proposal to give a “pass” on transportation analysis to any project that merely meets the regional average or better for VMT — she believes the bar should be higher. She also didn’t want to see a blanket “pass” for all projects within one-half mile of transit, given that there are certainly some bad projects near transit, like parking lots, that should have to account for their traffic impacts. Finally, she didn’t like OPR’s inclusion of language in the proposed guidelines related to safety, which she fears could be a back-door way to encourage more automobile-oriented mitigation measures from project developers.

I then gave my pitch for VMT as well, but I tried to put the SB 743 reform in context. The change to VMT certainly won’t solve the challenges that CEQA can pose for infill projects, but it will remove a big arrow from the litigation quiver of project opponents. More importantly, the reform could have a huge impact on sprawl projects. The mitigation measures for high VMT for these outlying projects could be potentially transformational. These measures could include requiring more mixed uses in the developments (like adding retail and office to residential sprawl), shuttles and new transit lines, more affordable housing, and transit passes and the like. In short, it will change the character of sprawl in California and also make it more expensive and legally difficult to get these projects built in the first place.

But for some reason, no one seems to be talking about this potential effect on sprawl, perhaps given all the hullabaloo about how infill projects will supposedly be hurt by the new VMT analysis. It’s even more bizarre given that under this proposal, essentially all infill projects would be exempt from any transportation analysis at all. And if they do have to do an analysis, it will be under the far simpler and cheaper VMT metric.

Jennifer Hernandez went last. She began her presentation by describing CEQA’s negative impact on all sorts of projects, but especially infill. She debuted a new study that her firm conducted on CEQA litigation, which apparently shows how so much of it is directed at infill and infill-related projects. As a result, she argued that California needs wholesale CEQA reform, and not just this incremental reform. In her perfect world, CEQA would set broad environmental standards and then provide deference to agency decision-making to meet those standards.

She didn’t engage much with the details of the SB 743 guidelines, only arguing that they essentially introduce more “uncertainty” into the process and that OPR should use its discretion (which I don’t believe it has under the law) to simply remove transportation analysis entirely or possibly set a broader standard on transportation impacts that would be easier for agencies to meet. In one of her few specific criticisms of the guidelines, she questioned how planners can run a VMT analysis on projects like schools, hospitals and churches, as an example of the “uncertainty” created by this new metric (in fact, the models cover these uses).

In the Q&A, I applauded the Holland & Knight study for bringing facts and data into the otherwise anecdotally driven debate. But it’s important to keep in mind that the study only looks at the universe of CEQA litigation without a broader context for how rampant or not CEQA litigation is in the state. It’s one thing to say 55% [not the exact number in the study] of CEQA litigation targets infill, but what percentage of infill projects across the state are subject to CEQA litigation at all? Perhaps it’s relatively puny. But it would be nice to know to put these numbers in context.

The study also doesn’t capture the non-litigation effects of CEQA, such as the defensive decision-making at the project and planning level to avoid litigation. It also doesn’t capture the pre-litigation settlements and the administrative processes that don’t give rise to litigation. And of course it doesn’t capture the benefits of mitigation measures and the role CEQA plays in stopping bad outlying projects. Of course, these impacts are really hard to document, but we should keep in mind that we’re missing that picture when all we focus on is the litigation.

I also questioned the Holland & Knight “doom and gloom” view of how hard it supposedly will be to run a VMT analysis. The VMT models exist and are currently in use, and they are much easier and cheaper to use than traffic studies. And under the current guidelines, no projects would even need to bother with a VMT study at all in essentially all of the existing urban areas of California. Jennifer did not respond to these points.

Overall, it’s easy to make broad claims about the danger of injecting more “uncertainty” into CEQA and expressing fear of a new metric. But when you actually grapple with the details of what OPR is proposing, it’s hard to see what the fuss is about, at least if you’re pro-infill. Of course, if you’re pro-sprawl (or at least anti-infill), then you should be worried about these guidelines.

OPR is almost certainly going to change the guidelines significantly, so in many respects we’re debating a moving target. But their basic approach is legally and practically sound and seeks to achieve the exact outcomes California needs on the ground. I tried to make that point on Tuesday night. In the meantime, we’ll have to stay tuned to see how OPR revises their proposal.

Last year, the California legislature passed badly needed reform to change how agencies evaluate a project’s transportation impacts under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). The Governor’s Office of Planning and Research (OPR) was tasked with coming up with new guidelines for how this analysis should be done going forward. As I blogged about, the new proposed transportation metric, vehicle miles traveled (VMT), will inherently benefit infill projects and punish sprawl projects, because infill by its nature decreases VMT.

But you would never know that if you just read the misleading diatribe against the new guidelines by the influential large law firm Holland & Knight. Right off the bat, Holland & Knight attorneys get it wrong on both the legislation and the guidelines:

OPR proposes to dramatically expand CEQA by mandating evaluation and mitigation of “vehicle miles traveled” (VMT) as a new CEQA impact and single out certain infill projects as the first category of projects that must comply with this new VMT regime before it becomes mandatory for all projects in 2016.

In fact, the opposite is true. The guidelines essentially exempt any project within a half-mile of transit — or in areas that are below the regional average VMT levels — from any transportation analysis under CEQA. And lest you think that’s a small area, keep in mind that almost the entirety of urban Los Angeles is within a half-mile of a high quality transit stop, due to the extensive bus network.

A little less of this, please

What OPR is actually doing is eliminating the existing “level of service” (LOS) transportation analysis (which basically means auto delay) from CEQA in infill areas first and statewide by 2016. OPR is then replacing it with a VMT study requirement only in areas with high average VMT. Projects in low average VMT or transit areas either won’t need to do any transportation study whatsoever or won’t need to mitigate at all. That hardly equals an “expansion” of CEQA. Furthermore, the 2013 CEQA legislation specifically required OPR to come up with a replacement for LOS and called out VMT as the most likely substitute.

Holland & Knight attorneys then attempt to scare infill developers and their advocates by claiming that the new metric will lead to additional litigation. First of all, as mentioned, most infill projects won’t even need a transportation analysis under CEQA anymore, eliminating expensive and contentious traffic studies. Second, these traffic studies already trigger litigation all the time under the existing LOS transportation analysis, so it’s not like these guidelines are ruining the wonderful world for infill under the status quo. And finally, and most importantly, the OPR guidelines make lead agency decisions as bulletproof as possible on how to analyze transportation impacts under the new metric. How? By giving lead agencies discretion to pick the VMT model of their choice and to use their professional judgment in applying it to projects. LOS analysis certainly doesn’t have that kind of legal protection, as traffic studies are challenged all the time based on their methodology and assumptions.

But Holland & Knight attorneys protest that lead agencies lack affordable and easy-to-use VMT models, leading to more uncertainty:

[I]t must be acknowledged that we have few, if any, models that purport to be able to accurately characterize VMT at a project-specific level for infill projects. The absence of such models will lead to increased study costs (at a minimum) and litigation/enforcement uncertainty as “NIMBY” opponents will have a new tool to use in CEQA lawsuits aimed at stopping or delaying a project.

The reality is that agencies around the state are using off-the-shelf VMT models all the time, most notably for local climate action plans and for regional plans under SB 375. This is not a new field, and dozens of models exist for lead agencies to use their discretion to use.

Finally, Holland & Knight attorneys complain that the measures required to mitigate high VMT levels “go beyond CEQA’s statutory scope and delve into socioeconomic and land use policy planning issues that the legislature has repeatedly declined to include in CEQA.” I disagree. OPR’s suggested mitigation measures are sensible and targeted to reducing VMT, such as by improving access to transit, providing transit passes and bike-sharing, and reducing or unbundling parking. Ultimately, how else could a project with high VMT mitigate this impact? The goal here, after all, is to reduce driving and to use CEQA as a tool to encourage that reduction where feasible.

It’s unfortunate that Holland & Knight attorneys are attempting to spread this misinformation to their clients and beyond. The state needs to leave behind the old framework of prioritizing autos over transit, bicycling, and walking. At the same time, CEQA should require sprawl project developers to account for their impacts on regional traffic and air pollution. VMT is the most sensible metric to accomplish these goals, and OPR’s guidelines are well thought out, with opportunity for continued refinement from stakeholder input. Yes, it will involve a new framework and some getting used to. Yes, LOS will still exist in some local plans and agency analyses. But this is the beginning of a long overdue transition, and Holland & Knight should cease with the misinformation and let the state move forward.