California is not getting it done when it comes to public charging infrastructure for electric vehicles. The stations are too few and far between, unreliable, and crowded. Brett Hauser, CEO of charging company Greenlots, described the overall problem (for non-Tesla drivers) at a recent California Energy Commission hearing, citing a PlugShare.com survey of EV drivers:

[I]n terms of driver satisfaction or dissatisfaction is the confidence [for EV drivers] in knowing that wherever they’re going, that if they’re trying to plan a trip that is of significant range that there is a great risk that that charge station, when they get there, is either not going to be available or, in fact, will be broken. I think, as a matter of fact, when they surveyed, I think it was about 547 drivers, those drivers that were Tesla drivers, 93 percent of those drivers actually had confidence that that charge station would be up. But all others it was down to 33 percent. Okay, I mean and that’s on all of us.

At the same Energy Commission hearing, many of the major players on EV infrastructure in the state spoke about the lack of progress to date, particularly with respect to publicly funded infrastructure. The transcript is available on-line [PDF].

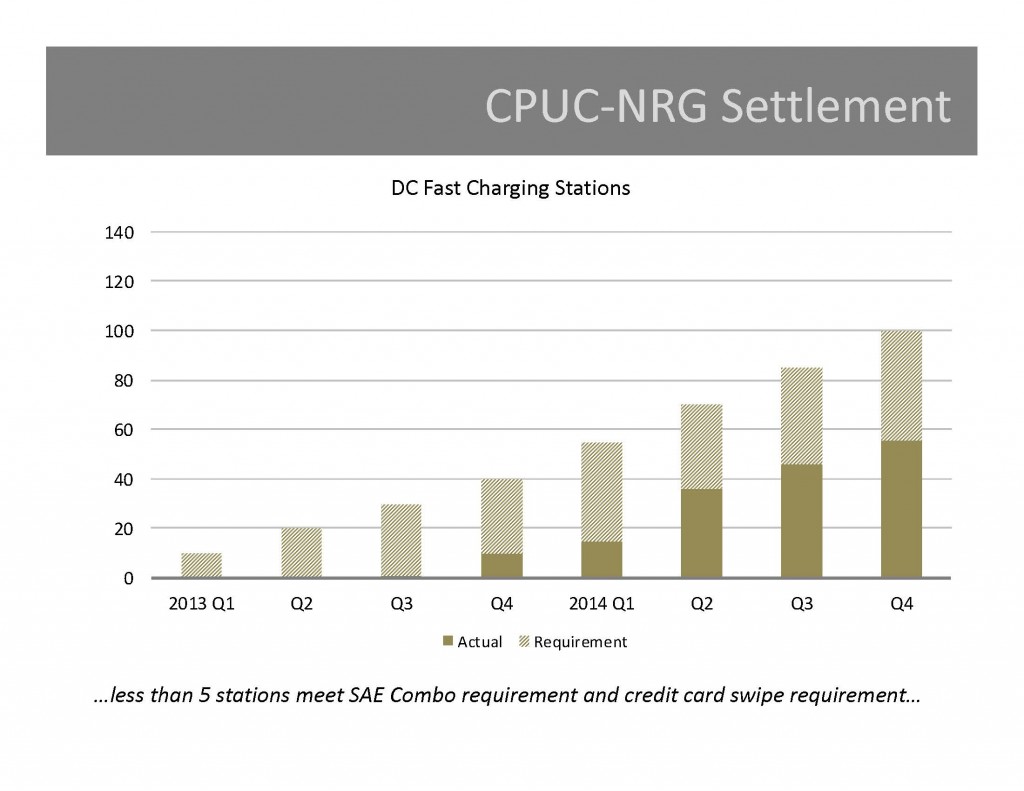

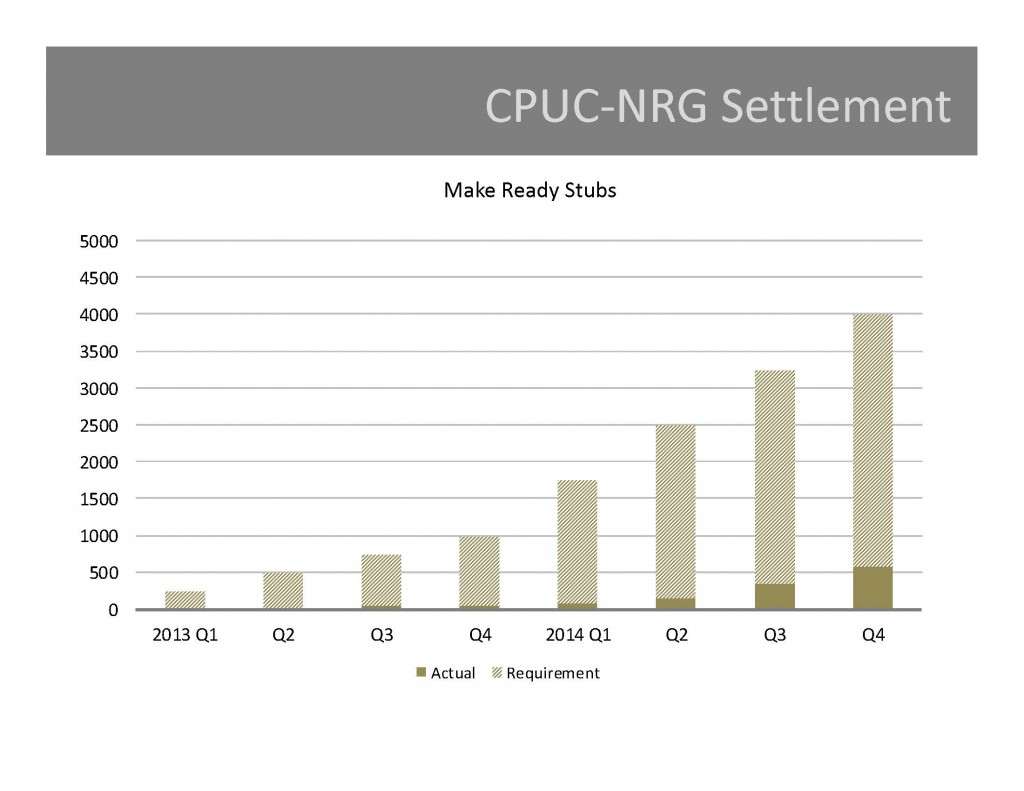

Perhaps the most striking revelation from the hearing was eVgo’s inability even to come close to meeting the $100 million settlement terms on EV infrastructure spending [PDF] that it agreed to in 2012. NRG, eVgo’s parent company, had reached the terms with the state for the devious corporate behavior of one of its acquired subsidiaries back in the rolling blackout days circa 2000. These charts from the California Public Utilities Commission presentation [PDF] sum up the dismal state of eVgo progress:

It’s gotten so bad that the agency is now hiring an auditor to determine the causes of the non-compliance.

So what gives? NRG/eVgo representative Terry O’Day explained that the siting process for these charging facilities has been extraordinarily complicated. He described it as a multi-step process that typically takes 9-12 months:

And the steps along the way include host approvals for retail tenants and for landlords. It includes utility interconnection. It includes permitting.

He also described some critical gaps in the system, such as in West Los Angeles and San Francisco’s peninsula and East Bay where there’s an “older building stock” that makes siting more difficult. He also noted a big gap in rural Northern California around the faux state of Jefferson. Safety, lighting, and handicap accessibility are all big factors:

You know, we need to plan these stations to consider this edge case of a single mom, with two kids, at 11:00 at night, in rural Northern California, when it’s raining. And that station better work because we took — we convinced that driver to come out to that station in the middle of a rural community. That means it also has to be available.

But even in overcoming these challenges, a larger problem emerges: the lack of a viable business model for private sector ownership of the stations. As Charlie Botsford, project manager for the West Coast Electric Highway, described:

One of our stations took two years to develop. It was on Forest Service property. Don’t ever, whatever you do, put something on government property, especially Forest Service. That was Mt. Hood Ski Resort, so it was really, really difficult. So, I can give you all kinds of horror stories, war stories about siting fast chargers, and getting into lease agreements. A lot of it has to do with why, you know, what’s the motivation for putting a fast charger at a particular site. And, you know, because the business model is — to say that it’s weak is an understatement. It’s even weaker, by the way, for level 2. But for DC fast chargers, it’s a pretty weak business model.

Actually, the best business model that I’ve seen so far is Tesla and they do it for completely different, self-serving reason, purely for the convenience of their drivers. Wow, what an idea.

Complicating matters, the major automakers plan to introduce cheaper 200-mile range, all-battery electric vehicles in the next two years. Drivers’ charging needs are therefore about to rapidly change, as they’ll need more local overnight charging opportunities if they can’t charge at home or work and more interstate-based charging sites between major cities.

So it may be time to rethink how the public supports charging infrastructure in general. Tony Williams, R&D manager for Quick Charge Power LLC, drafted an open proposal to the Energy Commission:

I propose that our state fund a logical California West Coast Electric Highway system comprised of 40 multi-charger (2 minimum) “Plazas” that are powered by onsite batteries, and the batteries are replenished with solar, wind power where applicable, and “single” phase sub-20kW grid power to mitigate or eliminate “demand charges”. These sites would cost approximately $250,000 per site and be placed at 60-100 miles apart along the major corridors that already have freeways:

1) Los Angeles to Sacramento, via 5 and 99

2) Los Angeles to Las Vegas, via 15

3) Los Angeles to Phoenix, via 10

4) Los Angeles to San Francisco via 101

5) San Francisco to Reno via 80

6) San Francisco to Oregon via 101

7) Sacramento to Oregon via 99 and 5

8) San Diego to Yuma via 8These are the logical routes the Californians actually drive to already. With numerous 100-200 mile electric cars on the horizon from major auto manufacturers like General Motors and Nissan, and also premium auto makers like Tesla and Jaguar, these routes must be planned for the near future, but made capable with existing cars that have sub-100 miles ranges. For those cars, I recommend placing small 20kW DC chargers in between each Plaza site, which will not need batteries or infrastructure to eliminate demand charges.

Williams argues that the investment would be relatively small, or “just half the amount of money devoted to hydrogen cars for just one year (just $10 million) by our state,” with an additional $2.5 million to fund 50 additional low powered sites at $50,000 per site.

Of course, this plan won’t necessarily help condo and apartment dwellers who lack home charging options. But that could be addressed in part through new technologies, like chargers on streetlights and chargers that don’t need to be hard-wired but can roam around a parking lot. Plus greater utility involvement in funding urban chargers. Overall, if you combine this interstate charging plaza idea with improved local deployment, then California would be on its way to solving many of the EV infrastructure challenges.