Gas prices have been on the rise, reaching a high not seen since summer of 2015:

The price increases could have both a positive and negative effect on California and the country’s transportation politics and climate policies.

First, let’s look at the price increases, which have been volatile and uneven. As the Wall Street Journal reported last week:

“The crude complex has seen prices stall a bit near recent highs as the market weighs whether a rising tide of geopolitical risk and strong demand is enough to continue overshadowing U.S. production growth to force prices steadily higher,” said analysts at Schneider Electric.

But analysts expect price declines to remain limited: the potential loss of Iranian oil from global markets might open up extra space for U.S. exports, while the market has already tightened due to falling Venezuelan output, worldwide economic growth and production curbs from OPEC members.

If the price rise lasts, it could affect some key transportation policies and efforts to decarbonize driving. On the positive side for the environment, high gas prices could:

- Boost battery electric vehicles: higher gas prices will encourage people to buy more fuel-efficient vehicles, particularly electric vehicles. That’s an all-around win for the environment and long-term efforts to transition away from fossil fuels.

- Reduced vehicle miles traveled: higher gas prices mean people will be less likely to drive as much, reducing emissions in the process and making it easier to meet our climate goals and decreasing the demand for outlying sprawl housing.

But on the negative or mixed side, higher prices could:

- Help California’s gas tax repeal measure: the California Legislature took a courageous step last year when they voted as a super-majority to increase the gas tax to pay for transportation infrastructure maintenance. Republicans have now put the tax on the November ballot as a voter-initiated repeal measure, hoping it will energize their base to come out to vote. High gas prices in November could give this measure real political life (although I’d rather see legislators investigate possible oil industry price manipulation instead).

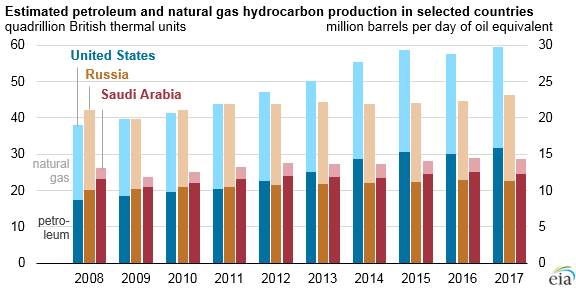

- Possibly reduce economic output with less money for investment in clean technology: high gas prices could potentially depress sectors of our economy, which could dampen investment in clean technology generally and undermine political will to tackle environmental problems. But high gas prices in the U.S. cut both ways: while it hurts consumers, it helps oil and gas producers. And in the U.S., we’re among the global leaders in fossil fuel production, as this EIA chart shows:

So high gas prices could boost oil-producing states and the economy for those residents, which could have varied effects on those states’ willingness to pursue clean transportation policies (although admittedly probably minimal, as many of these states are dominated by Republicans and unlikely to support pro-clean tech policies anyway).

Overall, high gas prices could be a political win for most clean transportation policies and technologies, but with some potentially negative consequences as well.

It’s no secret that our transportation infrastructure is badly underfunded. The federal gas tax hasn’t been raised since 1993 and doesn’t keep pace with inflation, leading to a 30 percent effective reduction in revenue. And vehicles are getting more fuel efficient. While that’s a good thing in general, it means less revenue from the gas tax for roads, bridges and the like.

With new revenue coming in, from an environmental perspective, we could ensure that the money gets spent as cost-effectively as possible and that it allows for more transportation options, such as for transit, bike, and pedestrian usage.

KQED Radio in the San Francisco Bay Area covered this topic in the context of rising gas prices. Reporter Bryan Goebel interviewed me for the piece, which you can list to here:

Audio PlayerThe falling prices at the pump have been welcome news for drivers and consumers. It’s hard not to feel like gas prices are the ultimate determinant of our economic well-being. When they go up, the economy stalls, such as in the 1970s, early 2000s, and then the recent economic malaise following the Great Recession. And when they go down, the economy seems to hum, like in the 1990s and now with our increasingly robust economic recovery. Cheap energy underpins virtually everything we do, and transportation fuels are the key inputs for our industrial machine.

We know this industrial production and activity comes at an environmental cost. But is there reason to believe this time is different? There’s no doubt cheap gas means more pollution, at least in the short run. It’s encouraging less efficient vehicle purchases (SUV sales are up although electric vehicle sales so far are holding steady), more driving, and more economic activity that tends to produce more carbon emissions.

But there are environmental positives, some immediate and some more potential. In the immediate future, cheap oil means environmentally destructive oil and gas extraction methods, such as fracking, become too expensive to continue relative to the cheap global price of oil. The decrease in investment in these methods could have long-term consequences on supply, once this oil boom fades. And since these extraction methods often produce both oil and natural gas, the slowdown could drive up natural gas prices as a byproduct. That in turn could make renewables more cost-competitive and possibly discourage wasteful gas consumption, spurring efficiency overall.

But there are environmental positives, some immediate and some more potential. In the immediate future, cheap oil means environmentally destructive oil and gas extraction methods, such as fracking, become too expensive to continue relative to the cheap global price of oil. The decrease in investment in these methods could have long-term consequences on supply, once this oil boom fades. And since these extraction methods often produce both oil and natural gas, the slowdown could drive up natural gas prices as a byproduct. That in turn could make renewables more cost-competitive and possibly discourage wasteful gas consumption, spurring efficiency overall.

The other long-term potential environmental good is that a booming economy is a big factor in making voters more likely to support environmental measures (the so-called “affluence hypothesis”). So as many people experience rising income or more disposable cash from cheaper energy, environmental leaders should take the opportunity to solidify environmental policies. In California, that would mean legislating 2030 and maybe even 2050 greenhouse gas reduction goals to extend AB 32 (the state’s climate law) authority beyond 2020. That could also mean switching from the gas tax to a vehicle miles traveled tax to develop a more stable source of funding to repair existing roads and pay for new transit, pedestrian and bike infrastructure. Legislators could develop a permanent funding source to help build more affordable housing near transit. And it could also mean reforming Proposition 13 to allow local governments to raise voter-approved revenue for transit with a 55% majority.

At the national level, a booming economy could undermine efforts to rollback EPA regulations to reduce pollution from power plants, while correspondingly lead to more support for a nationwide vehicle miles traveled tax to fund transportation. (I’d love a national policy on carbon, too, but I don’t think that even a booming economy could overcome the structural impediments that disproportionately empower rural, fossil-fuel dependent states in the federal decision-making process.) And maybe a booming economy could make it easier for the Obama Administration to negotiate a more meaningful international climate treaty in Paris next year.

So the potential upsides of cheap gas are huge, while the known immediate downsides may be unavoidable. Let’s hope our environmental leaders capitalize on this opportunity while they have it. Because if history teaches us anything, it’s that cheap gas never lasts.