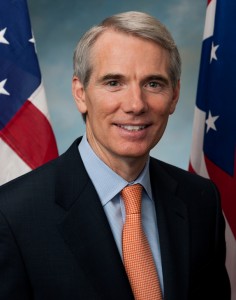

Perhaps even more encouraging was the bipartisan authorship, with Senator Rob Portman (R-Ohio) co-authoring along with Senator Jeanne Shaheen (D-New Hampshire). Portman was one of just five Republican senators to admit earlier this year that climate change is real and that humans are playing a role.

Here are some details on the bill from the Cleveland Plain Dealer:

The bill’s features aren’t exactly sexy. Portman’s staff says the bill “establishes a voluntary, market-driven approach to aligning the interests of commercial building owners and their tenants to reduce energy consumption.” It exempts certain electric resistance water heaters from pending Department of Energy regulation.

It requires federal agencies to coordinate strategies on energy-efficient information technologies. And it requires that federally leased buildings without Energy Star labels disclose their energy usage when practical.

That won’t quite fit in a soundbite response to the NRDC and Portman’s other environmental critics.

Yet Portman explains it all as simply “good for the economy and good for the environment.”

It’s easy to get caught up in solar panels, batteries, and electric vehicles (I certainly do), but if we don’t get more efficient with the energy we have, those other technology pieces won’t be enough. This bill is overall a pretty small step, but it’s solidly in the right direction.

A new UCLA study seems to suggest so:

According to UCLA researchers, the least effective way to get a Los Angeles family to save electricity is by telling them how much they’ll save in the process — mostly because it’s not a whole lot.

Instead, researchers said it was far more persuasive to tell energy consumers just how many pounds of pollution their power usage generated, and how that pollution has been linked to diseases like cancer and childhood asthma.

If this study is accurate on a broad scale, it means California — and the U.S. — has been going about things all wrong on the energy efficiency effort, and for a long time and with a lot of money. For example, the 2009 stimulus involved millions of dollars for energy efficiency, most of which yielded little result here in California.

But the good news is that in the end, it all boils down to the same thing: providing energy users with data on the impacts of their usage patterns. Whereas up until now we’ve thought they should know the economic costs, such as by providing them with information on lifetime energy costs for appliances, maybe we just need to switch that information over to public health costs, as this study suggests. And the study also indicates how powerful public health data can be in the fight to get public support to reduce pollution more generally.

Overall, a very eye-opening bit of research. I hope there is significant follow-on to test the results in different communities and at a broader scale.

The United Kingdom has been a leader on encouraging building owners to upgrade the energy performance of their properties. The country mandates disclosure of building energy performance during sale or lease to make new owners aware of the inefficiencies. And it launched the “Green Deal” program in 2013:

The United Kingdom has been a leader on encouraging building owners to upgrade the energy performance of their properties. The country mandates disclosure of building energy performance during sale or lease to make new owners aware of the inefficiencies. And it launched the “Green Deal” program in 2013:

The scheme aimed to encourage millions of households to take out loans to fund the cost of work such as installing insulation or new boilers, with the loans paid back in instalments on their energy bills. It was marketed around the idea that the household would end up better off, because the repayments would be lower than savings the household enjoyed from being more energy efficient.

But things didn’t go as planned:

[I]t has been beset by problems from the outset, with high interest rates on loans widely regarded as unattractive, and ministers forced to admit that savings were not guaranteed. Fewer than 4,000 households had signed up for ‘Green Deals’ by the end of July.

The troubles with the UK program mirror the challenges that California has faced with its Energy Upgrade program:

According to an analysis of state data by the San Francisco Chronicle, California has only supported 12,200 home efficiency retrofits under its Energy Upgrade California program since 2011. The stated goal of the program is to service over 100,000 homes.

The culprit in California is the complex administrative process to qualify for the rebates and incentives. I know from personal experience. When I tried to access the financial incentives from Energy Upgrade California when I wanted to add insulation to my attic, the program required an expensive energy audit both before and after, even though I had already had an audit done the calendar year before. So I just skipped the audit and the incentives entirely but still got the work done.

Cracking this nut is difficult. Each building is different, and even though the savings are potentially significant, many property owners don’t want to deal with the hassle or expense of an upgrade to the building. Maybe California and the UK can learn from each other, because we’re definitely going to need to make the process and incentives as seamless as possible to encourage people to undertake these upgrades.

On the heels of my blog post last week about the growth in local PACE financing programs for clean energy, California is unveiling a massive 17-county PACE program today. As I discussed in the original blog post, PACE programs give building owners access to capital for clean energy improvements, such as rooftop solar and energy efficiency upgrades and appliances. The owners pay the money back as an assessment on their property tax bill.

In 2010, the federal government essentially quashed residential PACE with an unfortunate regulatory ruling calling into questions mortgages with PACE liens. However, today’s announcement represents a significant bounce-back for PACE. As the San Francisco Chronicle reports:

17 California counties will announce the launch of the nation’s largest PACE program yet, CaliforniaFirst. Backed by a new insurance fund created by the state, they are confident they can put the federal government’s concerns to rest. And cut energy use in the process.

“We always knew that this could be a very powerful tool to help people save energy and save money,” said Cisco DeVries, CEO of Renewable Funding, an Oakland company that will run CaliforniaFirst. “It’s exciting and it’s gratifying to see this come back around.”

The 17 participating counties represent 14 million residents, more than a third of California’s population. Bay Area counties taking part include Alameda, Marin, Napa, Santa Clara, San Mateo and Solano. San Francisco and Sonoma counties already have their own PACE programs.

The implications could be huge. Not only does it mean a lot more local energy efficiency improvements and economic savings, it means more local jobs, contributing to a growth industry of labor and business leaders that is becoming more politically powerful. It could also disrupt industries like solar leasing. After all, if you can buy your own solar array with semi-annual payments spread out over years that are less than your savings, why lease and not get the full value of the system?

Let’s hope this announcement will also encourage the feds to change their misguided policy, once they see their fears of mortgage losses will not materialize. Overall, it’s a good sign for California and the country.