Battery electric buses are already cost-competitive with fossil-fueled buses, based on their lower fuel and maintenance costs. Transit agencies around the country are starting to purchase them in bulk from companies like BYD and ProTerra.

But is electricity really cleaner than a natural gas-fueled bus? Union of Concerned Scientists tackled this question in California previously and found positive results, per UCS’s Jimmy O’Dea, and now they’ve taken their research nationwide:

We answered this for buses charged on California’s grid and found that battery electric buses had 70 percent lower global warming emissions than a diesel or natural gas bus (it’s gotten even better since that analysis). So what about the rest of the country?

You many have seen my colleagues’ work answering this question for cars. We performed a similar life cycle analysis for buses and found that battery electric buses have lower global warming emissions than diesel and natural gas buses everywhere in the country.

Here’s the UCS map:

Meanwhile, the buses are getting cheaper and better, as ProTerra’s CEO Ryan Popple explained recently to E&E News [paywalled]:

Meanwhile, the buses are getting cheaper and better, as ProTerra’s CEO Ryan Popple explained recently to E&E News [paywalled]:

When we started out, we could really only do circulator-style routes, and we needed a fast charger for every route. That was probably five years ago, and that was because our maximum theoretical range was probably 50 miles. Now we’re regularly seeing our electric buses do anywhere between 175 and 225 miles in real service. And with all sorts of topography.

But despite the technological advancements and environmental benefits, supportive policy is still needed. Here’s the top of Popple’s policy wish list:

It is at the state of California, and it is the Innovative Clean Transit rule, the ICT. That is headed to the California Air Resources Board for an initial vote, I think, in September, and it could be fully implemented by the end of this year. What that ruling will do is set a long-term target for every transit vehicle in the state of California and a date certain by which it must eliminate its tailpipe emissions, so basically it has to become a zero-emissions vehicle… The reason it matters to us is just so that the industry can move forward with long-term planning on electric fleets.

And as more transit agencies move forward with zero-emission vehicles, we now have assurance that the clean air benefits are real — all across the country.

BAIC EC-Series, the top-selling EV in China

The Trump administration may be pulling back on clean cars, but China is all in. The latest numbers from China on passenger electric vehicles and electric bus sales are impressive, and they point to a future of global dominance for Chinese automakers in the EV world.

First, let’s look at passenger electric vehicle sales, as Clean Technica covered:

After the usual off-season (January and February), March came and electric car sales surged to 59,000 units in China, up 85% year over year (YoY). Quarter 1 2018 sales doubled compared to the same period last year, to over 122,000 units.

Consequently, the 2018 plug-in electric vehicle (PEV) share surged to 1.8%, not that far off from the 2.1% of 2017, and with sales expected to pick up significantly as the year advances, the 2018 PEV share should end north of the 3% threshold.

Last month, the Chinese OEMs represented roughly 40% of all PEVs registered globally, an impressive number that is sure to increase during 2018, possibly even beating its 46% record of last year.

Meanwhile, the Chinese EV automaker BYD had its second-best month ever with 13,100 registrations, just below their 16,000 units sold last December. Analysts expect BYD to start posting 20,000-plus performances in the second half of the year, putting it on par with Tesla’s sales forecasts.

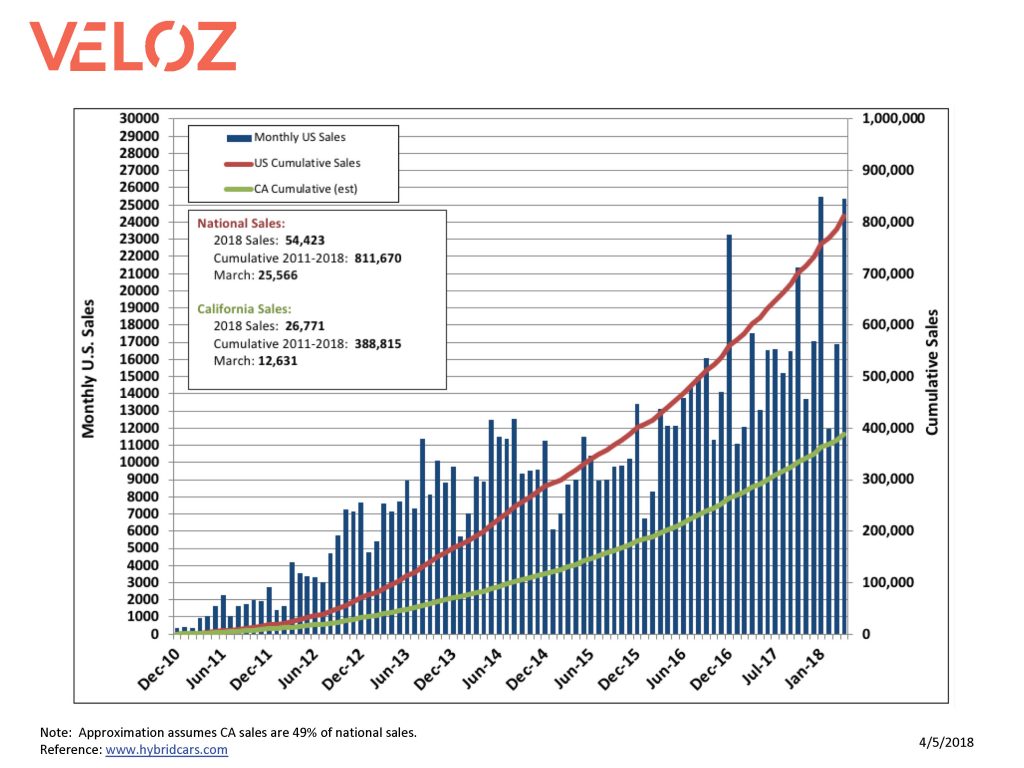

To put those Chinese numbers into perspective, here are the most recent EV sales figures in the U.S. and California since 2011:

So while the entire U.S. has logged 54,423 EV sales in the first 3 months of 2018 (with almost half of that total — 26,771 — from California alone), China hit 59,000 in just one month, with the trend lines only going up.

So while the entire U.S. has logged 54,423 EV sales in the first 3 months of 2018 (with almost half of that total — 26,771 — from California alone), China hit 59,000 in just one month, with the trend lines only going up.

But it’s not just passenger vehicles. China is heavily investing in electric buses. As Bloomberg reported:

China had about 99 percent of the 385,000 electric buses on the roads worldwide in 2017, accounting for 17 percent of the country’s entire fleet. Every five weeks, Chinese cities add 9,500 of the zero-emissions transporters—the equivalent of London’s entire working fleet, according Bloomberg New Energy Finance.

Much of China’s commitment to electric transportation is due to local air quality concerns. But the country’s leadership surely sees a path to economic domination of the transportation technology of the future, just as they dominate manufacturing in other industries.

While China’s commitment to EVs and electric buses is certainly good for the environment and fight against climate change, it means the U.S. federal government is missing out on a golden economic opportunity, let alone environmental one. EVs are here to stay, and at this rate, it will be China cashing in and not the U.S.

What value does rail transit bring to a city? The bottom line is increased capacity. You can squeeze a lot of people into multiple rail cars, all driven (or overseen) by one conductor in the lead car.

What value does rail transit bring to a city? The bottom line is increased capacity. You can squeeze a lot of people into multiple rail cars, all driven (or overseen) by one conductor in the lead car.

There are other benefits, too, of course, like fast electric acceleration (if it’s not diesel powered), smooth riding (if the rails are in a separate right-of-way and not stuck in street traffic), and general reliability (again, if the rail travels in a separate right-of-way and not slowed by cars). And as a uniquely permanent infrastructure investment, with tunnels and elevated tracks (sometimes) and fixed stations, it can help stimulate real estate investment to encourage thriving, walkable neighborhoods around it.

But technology may make this beloved, nineteenth century style of transit propulsion obsolete. I’m talking about electric platooning buses, which makes use of the self-driving car technology that is rapidly advancing. As the U.S. Department of Energy defined it in a recent post about platooning trucks:

Platooning involves the use of vehicle-to-vehicle communications and sensors, such as cameras and radar, to virtually connect two or more trucks together in a convoy. The virtual link enables all of the vehicles in the platoon to communicate with each other, allowing them to automatically accelerate together, brake together, and enables them to follow each other at a closer distance than is typically possible with unlinked trucks.

If we can place 8 or 10 buses in a row, have them all accelerate electrically and brake together, be separated by just a few inches, and be operated by just a single lead driver (or computer), isn’t this essentially just a long train?

The benefits would be immense:

- Massive cost savings: with electric buses, you don’t need to lay tracks or have overhead or down-below wiring to power trains. You don’t need substations along the way. The buses would be battery operated (as they already are, through companies like BYD and Proterra), so they could charge in central, convenient places. Sure, that requires charging infrastructure. But it’s much less expensive than wiring an entire route.

- Faster build times: transit agencies could build transit lines much more quickly without all the wiring infrastructure and tracks. Tunneling and overpasses still take time, but transit agencies basically just need to put down pavement and striping. Bus rapid transit lines can be built in about a fifth of the time as rail (and at a fifth of the cost), meaning a city can get a lot more transit, a lot more quickly.

- Operational flexibility: the buses would be free to travel on surface streets as needed, giving transit agencies much more flexibility to move buses around as needed.

And the potential downsides? First is the technological uncertainty, as platooning is still being tested. Second, and related to the first point, is the cost and range of the battery. But as I mentioned, electric buses are already being used now, battery prices are falling dramatically, and energy density is improving. True, the buses have higher upfront costs, but they offer significant and offsetting savings on operations and maintenance. Finally, we’d need more charging infrastructure for the buses, as mentioned. Although again, that infrastructure is proven — and simpler than overhead lines or third rails.

But there’s one additional important point here: the prospect of electric platooning buses should not be used as an excuse to kill or postpone new rail transit proposals in the works today. City residents still need the infrastructure that goes with a separate right-of-way for rail, even if the technology changes. They need tunnels, grade separation, elevated lines, dedicated lanes, and overpasses and underpasses to keep rail out of street traffic. Even if platooning electric buses happen soon, that construction will still be put to good use, albeit with ripped out tracks and overhead lines.

But as transit agencies think about other types of rail upgrade projects, like converting the Orange Line bus rapid transit in the San Fernando Valley in Los Angeles into light rail, maybe they should take a step back and assess the state of platooning electric bus technology. That Orange Line project in particular is costly, and the dedicated right-of-way already exists to convert to electric bus. If rail construction is underway in 2020 or 2021 just as electric platooning buses are market-proven, it will be a giant waste of money.

So transit advocates should still want rail projects to move forward, and cities will still need dedicated rights-of-way, separate from car traffic. But looming around the corner may be a technology solution that could dramatically reduce costs and construction time for major transit projects. Even for those who will always love steel wheels on rail, it’s got to be hard not to see the appeal.