High housing costs are driven by two factors: increasing demand from a booming economy and lack of new supply to keep up. Now we have data that show how the rising costs are affecting low-income people of color the most in the greater San Francisco Bay Area.

UC Berkeley’s Urban Displacement Project and the California Housing Partnership document how rising housing costs between 2000 and 2015 have displaced these populations into new concentrations of poverty and racial segregation in the cheaper outskirts of the region, while prompting many to move out of the area altogether.

As an example from the study:

Between 2000 and 2015, as housing prices rose, the City of Richmond, the Bayview in San Francisco and flatlands areas of Oakland and Berkeley lost thousands of low-income black households. Meanwhile, increases in low-income black households during the same period were concentrated in cities and neighborhoods with lower housing prices—such as Antioch and Pittsburg in eastern Contra Costa County, as well parts of Hayward and the unincorporated communities of Ashland and Cherryland.

What can we do about these trends? Well, there’s little to do on the demand side, in terms of slowing the economy (which will happen during a business cycle downturn at some point anyway). Perhaps there are demand-suppressing options such as taxing vacant property or second homes at higher rates in the meantime. But there are no simple solutions.

So that leaves addressing the supply side, which means building more homes close to jobs (subsidies for affordable housing could help, too, but wouldn’t come close to meeting demand unless in the hundreds of billions dollars). And ironically the solution of building more infill homes is anathema to many advocates against displacement, who worry — sometimes rightly — that infill projects will displace existing low-income renters.

But by wholesale blocking solutions to more infill housing generally, such as SB 827 earlier this year, these same advocates are worsening the problem they care about, as the new data show. Unless we get a handle on high housing costs, the problem will only intensify.

It’s a conundrum that has to be addressed, if the state is ever to fix this economic, moral and environmental crisis brought on by the housing shortage.

One of the common knocks on allowing new home-building near transit (as SB 827 would allow) is that it will displace low-income renters and gentrify low-income neighborhoods. The nightmare scenario for these tenants is that a developer buys and demolishes their low-income, single-family or small multi-unit building and then builds a luxury mid-rise in a fast-gentrifying neighborhood. The tenants are kicked out and can’t find comparably priced housing in their neighborhood.

One of the common knocks on allowing new home-building near transit (as SB 827 would allow) is that it will displace low-income renters and gentrify low-income neighborhoods. The nightmare scenario for these tenants is that a developer buys and demolishes their low-income, single-family or small multi-unit building and then builds a luxury mid-rise in a fast-gentrifying neighborhood. The tenants are kicked out and can’t find comparably priced housing in their neighborhood.

But let’s explore why this dynamic might happen. A neighborhood is more likely to “gentrify” if higher-income people can’t find new housing elsewhere. They’ll buy up existing buildings in places like San Francisco’s Mission or Venice in Los Angeles, which otherwise house predominantly low-income residents.

And why can’t any of these tenants who are kicked out find comparably priced housing nearby? Primarily because local governments haven’t allowed enough new home-building, particularly subsidized affordable units, to stabilize prices and give low-income residents a chance to stay in their communities. So the current housing shortage puts displacement and gentrification on steroids.

Yet many advocates for low-income renters continually shoot down options to build new market-rate housing, even if that market-rate housing would include fees and requirements to build a certain amount of affordable units. Their argument is that the “luxury housing” that would result will only contribute to gentrification and displacement.

So what does the academic literature have to say on this subject? The Urban Displacement Project at UC Berkeley (in collaboration with researchers at UCLA and Portland State) tackled this question in a research brief last year. Here are their key findings, based on a study of the relationship among housing production, affordability and displacement in the San Francisco Bay Area:

- At the regional level, both market-rate and subsidized housing reduce displacement pressures, but subsidized housing has over double the impact of market-rate units.

- Market-rate production is associated with higher housing cost burden for low-income households, but lower median rents in subsequent decades.

- At the local, block group level in San Francisco, neither market-rate nor subsidized housing production has the protective power they do at the regional scale, likely due to the extreme mismatch between demand and supply.

The key takeaway here is that new affordable housing provides the most “bang for the buck” in terms of reducing displacement and gentrification pressure.

But the study also indicates that new market-rate housing may have three primary benefits for low-income tenants:

- It can reduce displacement pressure overall (although less so than new affordable units).

- This housing stock eventually “filters” over the coming decades into low-income housing, as it gets older and therefore less desirable to higher-income earners. As a result, it provides an investment in the unsubsidized housing of the future (most low-income residents live in market-rate housing, not subsidized units).

- New market-rate development can provide local governments with the revenue they need to fund new subsidized units, via impacts fees, inclusionary zoning, or higher tax revenue.

There’s no denying that displacement is a genuine concern, and policies to promote new housing need to take that concern into account. But opposing new market-rate housing, particularly near transit, is not a solution. In fact, it’s part of the problem.

It’s the trickiest issue for infill-boosters: how to make sure new development doesn’t displace existing residents, particularly low-income renters or owners? Gentrification is the big concern.

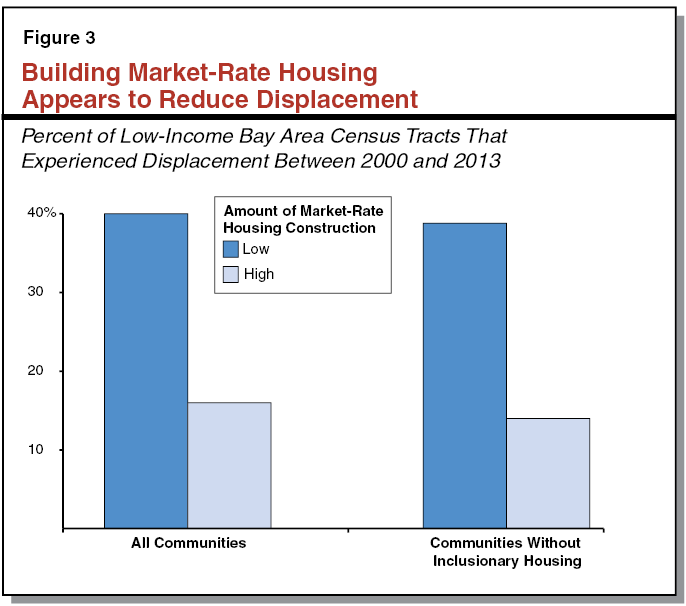

But a new report from the Legislative Analyst’s Office (LAO) suggests that cities that build more market-rate housing in general may suffer less displacement:

Encouraging additional private housing construction can help the many low–income Californians who do not receive assistance. Considerable evidence suggests that construction of market–rate housing reduces housing costs for low–income households and, consequently, helps to mitigate displacement in many cases. Bringing about more private home building, however, would be no easy task, requiring state and local policy makers to confront very challenging issues and taking many years to come to fruition. Despite these difficulties, these efforts could provide significant widespread benefits: lower housing costs for millions of Californians.

This trend holds true even without inclusionary housing policies that require new developments to subsidize affordable housing:

The bottom line seems to be that the more market-rate housing, the more overall prices stabilize, which in turn allows existing residents to be able to continue to afford to stay in their homes. It also provides new housing opportunities for middle- and high-income residents, so they don’t gentrify and push out lower-income neighbors.

The bottom line seems to be that the more market-rate housing, the more overall prices stabilize, which in turn allows existing residents to be able to continue to afford to stay in their homes. It also provides new housing opportunities for middle- and high-income residents, so they don’t gentrify and push out lower-income neighbors.

The report authors provide a helpful video to summarize the findings: