Big industry loves to demagogue the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), which requires environmental review for major new projects. But a new survey from the State of California shows that the law barely affects most projects where the state is the lead agency.

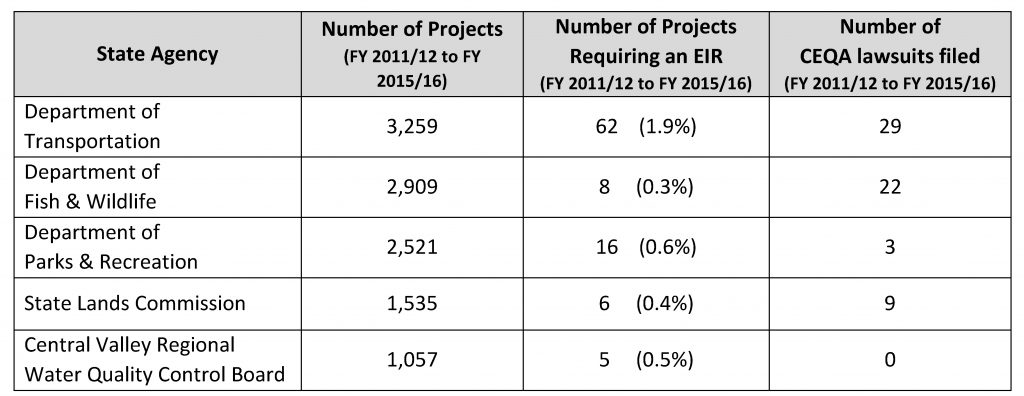

The study examined all state-led projects over a five-year period, from 2011 to 2016. First, 90% of the state’s projects were already exempt from the law, due to compliance with legislative or regulatory provisions that exempt certain types of projects. Second, a full-blown environmental impact report occurred less than one percent of the time, while litigation was virtually negligible. Here is the summary chart:

These findings are consistent with a 2016 study sponsored by the Rose Foundation, which found similarly low litigation rates (as I noted at the time):

These findings are consistent with a 2016 study sponsored by the Rose Foundation, which found similarly low litigation rates (as I noted at the time):

The number of lawsuits filed under CEQA has been surprisingly low, averaging 195 per year throughout California since 2002. Annual filings since 2002 indicate that while the number of petitions has slightly fluctuated from year to year, from 183 in 2002, to 206 in 2015, there is no pattern of overall increased litigation. In fact, litigation year to year does not trend with California’s population growth, at 12.5 percent overall during the same period.The rate of litigation compared to all projects receiving environmental review under CEQA is also very low, with lawsuits filed for fewer than 1 out of every 100 projects reviewed underCEQA that were not considered exempt. The estimated rate of litigation for all CEQA projects undergoing environmental review (excluding exemptions) was 0.7 percent for the past three years. This is consistent with earlier studies, and far lower than some press reports about individual projects may imply.

So while big polluters and sprawl developers and their law firm allies have gone to great lengths to demonize the law and the rare litigation that results, the facts just aren’t matching.

It’s still true that CEQA can be a barrier to new development. But based on the data so far, it’s just not a major one.

It’s taken a long time, but California finally is ready to make a significant change to speed environmental review for new transit and infill projects. The Governor’s Office of Planning & Research (OPR) announced on Monday that a compromise has been reached to implement SB 743 (Steinberg, 2013), a law that made major amendments to the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), the state’s law governing environmental review of new projects.

Back in 2013, the legislature passed SB 743 to change how infill projects undergo environmental review. Under the traditional regime, project proponents had to measure transportation impacts by how much the project slowed car traffic in the immediate area. The perverse result was mitigation measures to privilege automobile traffic, like street widening or stoplights for rail transit in urban environments or new roadways over bike lanes in sprawl areas.

But the true transportation impacts are on overall regional driving miles. An urban infill project may create more traffic locally but can greatly reduce regional traffic overall by locating people within walking or biking distance of jobs and services. Meanwhile, a sprawl project may have no immediate traffic impacts, but it typically dumps a huge amount of cars on regional highways, leading to more traffic and air pollution. As a result, the switch from the “level of service” (auto delay) metric to “vehicle miles traveled (VMT)” made the most sense. Most infill projects are exempted entirely under this metric, while sprawl projects would have to mitigate their impacts on regional traffic.

But OPR’s implementing guidelines with this change were held up by highway interests and their government allies, who don’t want the law to apply to highways. You can probably see why: highways are designed to do one thing only — induce more driving. And that would score poorly under this change to CEQA.

State leaders finally reached a compromise this month: the new guidelines could apply statewide to all projects (something only suggested by the statute), but new highway projects can still use the old “level of service” metric, at the discretion of the lead agency (see the PDF of the guidelines for more details at p. 77).

It’s an unfortunate but probably necessary concession to powerful highway interests. Even though freeways have consistently failed to live up to their promise of fast travel at all times, and instead brought more traffic, sprawl and air pollution to the state, many California leaders are still wedded to this infrastructure investment.

My hope is that the compromise won’t actually mean that much new highway expansion in the state. First, California isn’t planning to build a lot of new highways, outside of the ill-advised “high desert corridor” project in northern Los Angeles County. Second, even for new highway projects, CEQA’s required air quality review may necessitate an analysis of (and mitigation for) increased driving miles.

Either way, smart growth advocates can at least celebrate the good news that CEQA will finally be in harmony with the state’s other climate goals on infill development, transit, and other active transportation modes.

The guidelines though still need to be finalized by the state’s Natural Resources Agency, which will take additional months. I’ll stay tuned in case anything changes with the proposal during this time.

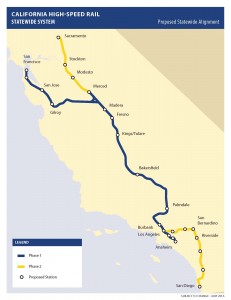

The California High Speed Rail Authority has been battered not just by Republicans in Congress but by the state’s primary environmental law, the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). The law requires environmental review of projects before they commence.

The California High Speed Rail Authority has been battered not just by Republicans in Congress but by the state’s primary environmental law, the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). The law requires environmental review of projects before they commence.

While that sounds sensible in concept, in practice CEQA has opened the authority up to lawsuits and delay from opponents up and down the route, from wealthy homeowners along the San Francisco peninsula to farmers along the San Joaquin Valley route who don’t want their properties bisected by the rail line.

The impact on the project from CEQA has been increased costs, delay, and in my view a less-effective route for the rail line (of course blame primarily rests on the politicians who gerrymandered the route in the first place, but due to CEQA it’s now impossible to correct the route without opening up the process all over again and inviting even more lawsuits).

While most people can agree that the agency should mitigate impacts where feasible and study these impacts in advance, CEQA lawsuits have instead served to drag out the high speed rail planning process and drive up costs. These effects undermine a project that is actually critical to long-term environmental goals, let alone economic goals related to mobility.

So it’s perhaps not surprising that the High Speed Rail Authority would love to escape the jurisdiction of CEQA. And that’s precisely the issue in today’s California Supreme Court argument in Friends of the Eel River v. North Coast Railroad Authority, Nos. S222472. This case actually involves a different rail line in California’s north coast, but the rail operator makes the same argument as the High Speed Rail Authority that CEQA doesn’t apply, due to federal rail law preemption of state law.

As my colleague Rick Frank summarized on Legal Planet:

This case raises the issue of whether federal law–specifically, the Interstate Commerce Commission Termination Act (ICCTA)–preempts the application of CEQA to a state-owned and funded rail line on California’s North Coast. Lower state courts have split on that issue, which has consequences far beyond the proposal to reactivate this previously dormant railroad line. For example, the same legal issue is raised in a federal case currently pending in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit involving California’s High Speed Rail Authority. In that federal appeal, the federal Surface Transportation Board–an obscure but important federal agency charged with implementing the ICCTA–notified the High Speed Rail Authority that it considers CEQA’s application to the planning and construction of California’s controversial High Speed Rail system to be preempted by the ICCTA. (Kings County v. Surface Transportation Board, Ninth Circuit No. 15-71780.) So the potential exists for conflicting rulings from the California Supreme Court and Ninth Circuit on the CEQA preemption question that would require the U.S. Supreme Court to resolve the issue. Additionally, the same preemption argument has regularly been made by oil and railroad companies who seek to ship crude oil by rail through California cities that oppose such oil shipments as unduly hazardous.

I listened to the oral argument today on-line (and I also had the opportunity to participate in a moot court last week for the plaintiffs). Based on the questions I heard from the justices, my guess is that the Supreme Court will find CEQA to be not preempted by federal law and therefore require the rail agency to enforce CEQA review.

But it’s a tough case. CEQA is open-ended by its nature, and the delays and mitigation measures that follow are likely to interfere with rail operations, which is precisely what federal law seeks to preempt. But it’s hard to imagine a state court voluntarily writing away its own state law. Instead, I would guess that the justices will frame the decision as allowing CEQA review in a limited fashion, given existing legal restraints from federal law.

But with the federal Ninth Circuit case pending on the same issue (this time explicitly involving high speed rail), we could very well end up with a split that will need to be resolved at the U.S. Supreme Court. So regardless of the outcome of this case, we’re likely to see more action to come on this question.

California’s cripplingly high housing prices in its big cities along the coast are caused by low supply, dating back decades, relative to population and job growth. But what is causing that shortage?

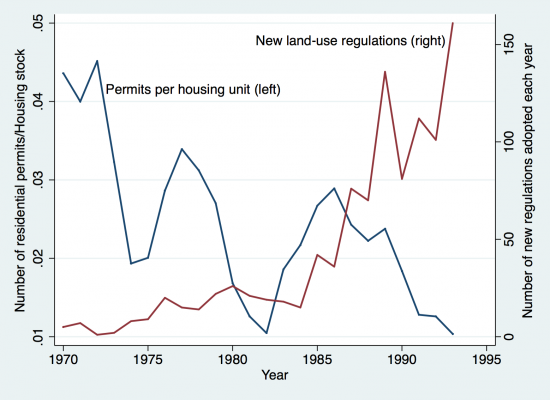

There are a number of theories, such as CEQA, Prop 13, and restrictive local zoning, but remarkably little evidence or study on this important question. Into this void, researcher Kristoffer Jackson recently conducted a study that links the increase in local land use regulations to the increase in housing prices:

California cities’ use of land-use regulation (including various zoning rules, residential density restrictions, and limitations on growth) increased precipitously from the mid-1980s to the early 1990s (see figure below). In a state known for making extensive use of voter initiatives, this increasing level of regulation was the result of rising anti-growth sentiment following periods of rapid population growth. Unsurprisingly, the most highly regulated communities back then—in the southern coastal region and in the San Francisco Bay area—still top the list today.

Comparing the rate of construction in cities that implement more land-use regulations to the rate in cities that implement less of it, I find that each additional regulation reduces a city’s housing supply by about 0.2 percent per year. The average California city used in my analysis has a population of roughly 55,140 with 21,740 homes. For such a city, adding a new land-use regulation reduces the housing stock by about 40 units per year. Reductions in a city’s housing stock are the result of significant declines in the rate of new-home building. The number of new homes built each year is reduced by an average of 4 percent per restriction. These reductions in new construction (and the overall housing stock) come through fewer single- and multifamily housing units, but the effect on the latter is much stronger, with an average of 6 percent fewer permits issued per regulation.

The study includes this helpful chart:

And as a related source of data, the UC Berkeley Terner Center released a development “dashboard” that tells you how much more housing production you could get with various policy changes in the San Francisco Bay Area.

All told, this research points to the huge impact that local land use policies have on restricting supply and driving up prices. Yet even Governor Brown’s proposal for “by-right” approval of new housing consistent with local zoning appears to have been shot down by labor and environmental groups, concerned about the loss of leverage over proposed projects — even if they conform with local zoning (to be sure, there were some legitimate concerns over the details, but the broad approach of the proposal is hard to argue with).

And so we find California to be a state tied in knots, with most communities preventing new development and therefore pushing it to the fringes, all while making the best of its cities unaffordable to new generations and most new arrivals.

How to unravel it? Further study on the causes of the housing shortage would be helpful, as well as an understanding of what policies have been the most detrimental to supply and why local communities enacted them.

But at the end of the day, it’s likely going to take state action to overturn some of the most draconian local regulations.

There’s been a lot of industry noise around the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), which requires environmental review for new projects and mitigation of impacts where feasible. Industry of course doesn’t like the expense, delay, and uncertainty that can be associated with this review, while environmentalists and other interests (particularly labor, homeowners groups, and rival businesses) like to have leverage over proposed projects to shape or sometimes kill them through delay.

There’s been a lot of industry noise around the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), which requires environmental review for new projects and mitigation of impacts where feasible. Industry of course doesn’t like the expense, delay, and uncertainty that can be associated with this review, while environmentalists and other interests (particularly labor, homeowners groups, and rival businesses) like to have leverage over proposed projects to shape or sometimes kill them through delay.

I’ve been critical of recent studies from the law firm Holland & Knight, purporting to show how CEQA litigation overwhelmingly targets environmentally “good” projects, such as infill, transit and renewable energy. These studies, in my view, were slanted and flawed.

But the sad fact is that we have little empirical study of this important law, which could help us evaluate claims from both sides in a fair manner.

Today, however, the Rose Foundation is releasing a new study, authored by the research firm BAE Urban Economics [PDF], that at least sheds light on the rate of litigation and costs of general CEQA compliance. The study found the following key points:

The number of lawsuits filed under CEQA has been surprisingly low, averaging 195 per year throughout California since 2002. Annual filings since 2002 indicate that while the number of petitions has slightly fluctuated from year to year, from 183 in 2002, to 206 in 2015, there is no pattern of overall increased litigation. In fact, litigation year to year does not trend with California’s population growth, at 12.5 percent overall during the same period.

The rate of litigation compared to all projects receiving environmental review under CEQA is also very low, with lawsuits filed for fewer than 1 out of every 100 projects reviewed under CEQA that were not considered exempt. The estimated rate of litigation for all CEQA projects undergoing environmental review (excluding exemptions) was 0.7 percent for the past three years. This is consistent with earlier studies, and far lower than some press reports about individual projects may imply.

Furthermore, looking at select case studies of four projects, the study authors found that direct environmental review costs for these four projects ranged from 0.025 to 0.5 percent of total project costs. Hardly a money drain for the chance to ensure advance environmental mitigation.

This study is helpful in putting the litigation in context, and I think it convincingly indicates that CEQA litigation is not a major problem when viewed from a statewide perspective.

Now to be sure, there are other costs associated with CEQA, such as delay, uncertainty, and defensive siting and project design. But just focusing on litigation, and telling the misleading story that it overwhelmingly affects environmentally beneficial projects, is not helpful for the broader debate.

Meanwhile, the state has made significant efforts over the past decade or so to relieve the CEQA burden on qualifying infill projects, such as SB 375, SB 226, and SB 743. We are still implementing those laws, through the development of regional transportation plans, local plans for infill, and new state guidelines. We would be better served to let those processes play out, and undertake further study, before making major changes to the law that could unintentionally benefit projects with negative environmental impacts.

This study underscores the need for that measured approach and hopefully portends more solid analysis of CEQA and its impacts in the near future.

Governor Brown’s proposal in his new budget to make certain housing developments eligible to be approved by the state “by right” has riled up not just local governments — who stand to lose discretionary approval over these projects — but some labor and environmental groups as well.

It’s pretty obvious why these groups are upset: the by-right state approval means they lose their leverage over projects under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), which can trigger lengthy local environmental review for discretionary approvals. And the governor’s proposal, as currently written, lacks safeguards to ensure that only environmentally beneficial projects are eligible for state approval.

Yet local resistance to new housing is a problem well beyond CEQA, and its cumulative effect — through restrictive local zoning, discretionary rejection of new housing, and citizen petitions and lobbying — has created a massive housing shortage in the state’s big cities. The inevitable result is high housing costs squeezing middle-income earners, with displacement and gentrification pushing out low-income earners. It’s becoming a national drag on our economy, while pushing new development out to the exurbs and over open space and farmland.

So in principle, state approval of certain housing projects is justified. But it needs to be the right kind of housing development, consistent with existing local plans. A relatively straightforward condition on these projects to be eligible is that they are located within a half-mile of a major transit stop and meet certain vehicle miles traveled (VMT) and greenhouse gas emission profiles. That would ensure environmental performance and that the projects do not contribute to sprawl.

The basic formula would be: 1/2 mile + VMT + GHG = by-right approval.

Of course, you’d probably have to layer in an affordable housing requirement as well to achieve political consensus. But increasing supply today will go a long way to stabilizing prices and therefore minimizing displacement, as well as creating the housing stock that will one day be affordable to low-income earners. And in the meantime, we can ensure that these new projects contain affordable units.

And for the labor groups, these multi-unit housing developments typically require higher-paying, high-skilled jobs that pay better than sprawl construction.

It would be a win-win, if our political leaders and advocates can arrive at compromise.

With the news that San Francisco is now mandating solar panels on new construction of certain sizable buildings, Brad Plumer over at Vox makes the point that the city could save more carbon emissions by allowing greater housing density:

According to a 2015 report from UCLA, the average person in the city of San Francisco emits just 6.7 metric tons of CO2 per year. By contrast, the average person who lives in the Bay Area emits 14.6 metric tons of CO2 per year. (The national average is about 17 metric tons.) So if San Francisco relaxed its restrictions and enabled, say, an additional 10,000 people to move from elsewhere in the Bay Area to the city, we could expect that to cut 79,000 metric tons of CO2 per year (to a first, crude approximation). This is three times as much CO2 as the solar panel law would save.

On a related subject, Shane Phillips rails against supposedly pro-environment, liberal coastal enclaves like San Francisco revolting against this kind of housing density:

On a related subject, Shane Phillips rails against supposedly pro-environment, liberal coastal enclaves like San Francisco revolting against this kind of housing density:

According to a 2015 NYU Furman Center report, rents and housing prices have climbed much more rapidly than incomes in places like NY, SF, and LA, while the reverse is true in places like Dallas, Houston, and Atlanta. Even without referring to the data, we’re all painfully aware of how quickly places like D.C. and San Francisco have become out of reach for lower-income, working class, and even many middle class households. This has had a disparate impact on people of color, the elderly, and other disadvantaged or vulnerable populations—and it’s happening in exactly the places that claim to care most about supporting these individuals.

I couldn’t agree more, but with one caveat: we can’t expect a relatively small city like San Francisco to assume all the responsibility for housing new residents in the Bay Area. Given its abundance of transit, it does make sense for the city to assume something like the majority of new growth, but Silicon Valley, Oakland, Berkeley, and anyplace with a BART station needs to step up, too.

Finally, I’ll just note that for those who complain that California makes it unduly difficult to build housing with laws like CEQA, it’s interesting to see how this housing shortage in urban areas is a national phenomenon. Not that reform of state laws isn’t needed, but it puts the problem in perspective.

Chip Johnson in today’s San Francisco Chronicle tackles the all-important question of the lack of housing in the Bay Area. He rightly focuses on the greed of those who seek to prevent new infill housing from being built.

But he goes awry in singling out the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) as the primary culprit. He cites the discredited Holland & Knight CEQA study as proving that infill projects suffer the most under CEQA, when that study defined the term so broadly that almost 90 percent of housing projects in the state are classified as “infill.” I wish he and others in the media would study up on this study before citing it, as it should not be used to inform policy going forward.

He then cites some CEQA reform measures that the study recommends, some of which I actually could support:

The study offered possible remedies: requiring anyone filing a new lawsuit under CEQA to state their environmental concerns, eliminating duplicate lawsuits for plans and projects that have already won approval, preserving the right of environmental review and public comment, and scaling back court-ordered invalidation of project approvals that harm health, destroy tribal resources or threaten the environment.

It doesn’t take a genius to figure out that if suburban sprawl is blocked for environmental concerns, and open lands are protected and urban in-fill is limited, it’s going to be very difficult to provide housing of any kind, except for the very wealthy.

I would favor eliminating duplicate lawsuits over plans and ensuing projects, which ultimately means strengthening the CEQA “tiering” provisions that allow projects to proceed by-right once they are consistent with an already-approved plan. And I would favor greater transparency about who is suing and the settlements they reach.

But the problem with this study (and this article) is that CEQA is not the only significant barrier to new infill development, which is mostly stopped by local zoning, lack of adequate infrastructure in infill areas, and perverse incentives caused by Proposition 13. Too often proposed CEQA “reforms” are really about benefiting sprawl, oil-and-gas, and other industrial projects, with infill used as a convenient, politically popular cover.

I’m afraid Mr. Johnson may have fallen into that trap by citing this issue and this study so prominently in his piece. Otherwise, I’m glad to see he’s taking on this issue.

The big law firm Holland & Knight has been on a crusade against California’s signature environmental law, the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), for a while now. I’ve had my tangles with partner Jennifer Hernandez there, who has issued some misleading studies to derail sensible CEQA reform.

Recently, the law firm tried to step up its game to issue a seemingly-comprehensive study of CEQA litigation to prove once and for all how the law is badly misused by NIMBYs and labor unions to stop badly needed projects. Among the chief conclusions, CEQA mostly targets infill projects, as well as transit and renewables.

The problem is, as my UCLA Law colleague Sean Hecht writes in a devastating takedown, the evidence doesn’t support their conclusions.

On infill, the study defines it as anything within incorporated city limits or adjacent to a development in unincorporated area — in other words an absurdly large geographical area that matches nobody’s definition of environmentally beneficial development. Hecht goes in for the kill:

Unsurprisingly, the definition includes projects that virtually no one would recognize as “infill” under any common definition. For example, this Wal-Mart in Milpitas appears to be classified as “infill,” along with several other Wal-Mart projects. So is Chandler Ranch, a new development in suburban Rolling Hills Estates that includes 114 single-family luxury homes plus a new golf course and clubhouse for the Rolling Hills Country Club. Moreover, some “infill” projects clearly do not provide benefits to their communities. The Bradley Landfill site, the subject of Comunidad en Accion v. Los Angeles City Council, is a waste management site in the middle of a poor Latino community. And another “infill” case, City of Irvine v. County of Orange, involved the expansion of a jail, partially on agricultural land, from 1200 inmates to 7,584 inmates. Many of the “infill” projects are industrial facilities, including asphalt and cement plants. The data presented just don’t support the idea that CEQA cases mostly target projects that support environmentally-sound development that is good for communities. The fact that projects challenged under CEQA are mostly located within the geographical boundaries of cities simply doesn’t prove anything.

On transit, Hecht found only a few lawsuits a year in the Holland & Knight dataset related to transit, including one that actually involved a paint and body industrial facility serving transit lines, rather than a transit project (whoops!).

On renewables, over the three-year study period, the report found just five solar projects and two wind projects that were challenged under CEQA. Hardly a damning amount, particularly given the questionable approval in the first place on one of the wind projects.

Hecht’s demo job of the report was badly needed and speaks to the problem of having ideologically motivated industry actors attempt a neutral “study” of something as hot-button as CEQA. In the future, I hope Holland & Knight attorneys stick to representing clients and leave the CEQA analysis to people who don’t have an axe to grind.

The battle between the California Infill Builders Federation and the Council of Infill Builders may be ending. I’ve written about the unfortunate spat before, where the nominally pro-infill Federation was pushing a bill to first roll-back, then delay, important reforms to the California Environmental Quality Act and its analysis of transportation impacts for infill. The California Planning & Development Report has a great paywalled piece on the fight that I summarized.

But now the Federation seems to be taking a much more sensible approach. In amendments posted Monday, the group deleted language that would delay the implementation of the regulations. Instead, the bill would give the Governor’s Office of Planning and Research authority to give all residential and mixed-use projects in “transit priority areas” (within 1/2 mile of major transit) an outright pass on transportation analysis. Outlying sprawl projects would still have to undergo a vehicle miles traveled (VMT) analysis.

This change would give much more certainty to infill project developers, who would otherwise have to determine if they should apply VMT or not (most wouldn’t have to do any transportation analysis anyway under the proposed guidelines, but it’s always nice to have certainty). And the “pass” wouldn’t apply to bad projects near transit, such as parking garages and big box stores. Those uses might still need to do a VMT analysis. Meanwhile, the preservation of VMT in outlying areas is critical to transforming how we treat sprawl in California.

Overall, it’s a welcome change. Let’s hope the “Infill Wars” are over and we can get back to the business of sensible CEQA reforms.