California has essentially been “going it alone” on comprehensive climate policy in the United States for the last decade or so. But starting in 2019, that might just change. Oregon’s legislature is seriously considering adopting a cap-and-trade program next year, which would signify a major in-country expansion of California’s approach and provide more momentum for multi-state action to address climate change.

This week I’m at the Oregon Coast Caucus Economic Summit in Lincoln City, Oregon, an annual event organized by the bipartisan coastal delegation in the state’s legislature. A key theme of the event is climate policy. Despite the hyper-partisan poisoning of the climate debate around the country, here Republican legislators seem comfortable discussing carbon policies.

Why the difference? Two reasons: first, the Oregon coast is experiencing the negative impacts of climate change, particularly from ocean acidification and its negative effect on local oyster farms. Second, the Oregon coast is impoverished, yet with significant forest resources, leading many coastal representatives to view a state-level carbon policy as an opportunity to generate revenue that can then be spent locally.

The speaker of the Oregon House of Representatives, Tina Kotek, is fully committed to adopting a cap-and-trade (or “cap-and-invest” as they’re calling it) program. But Kotek was rebuffed by Senate President and fellow-Democrat Peter Courtney this year due to the short even-year legislative session and complexity of the issue. However, at their joint lunch panel today, Senator Courtney pledged to bring the issue to a vote in 2019. Insiders I spoke with at the conference believe they will have the votes to pass it. The wildcard, however, is that the current governor, Kate Brown, is up for re-election this year and is facing a tough Republican challenger, funded in part by Nike founder Phil Knight.

But assuming the debate goes forward next year, the contours appeared to reveal themselves at the conference. Some businesses obviously don’t want the program at all, primarily out of fear of higher energy and transportation costs (although Oregon’s grid is already quite green and unlikely to be negatively impacts by any compliance obligations). The trucking industry wants any revenue raised to go to road repair, which would hardly be a way to encourage greenhouse gas reductions. However, this outcome might be unavoidable to some extent, due to a recent Oregon Supreme Court decision that limits funds raised from transportation to highway spending only. But I’m told creative workarounds could be found, such as using any proceeds to fund transit lanes on highways or electric vehicle charging stations along routes. Meanwhile, utilities would like to be exempt entirely from the program, much as they essentially were in the early days of the California program. The list of business concerns goes on from there.

The good news is that all of these issues can likely be resolved with robust discussion, study and debate. And based on what I’ve heard so far at the summit, state leaders are already well on their way. For those who are in favor of multi-state coalitions to address climate change, it’s a welcome sight.

After I just wrote that the cap-and-trade extension to 2030 throws a lifeline to high speed rail in California, I read in today’s San Francisco Chronicle that California Republicans think they’ve potentially “de-railed” their hated train by helping to extend the program:

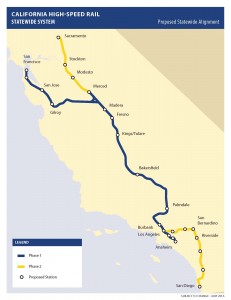

In extending California’s cap-and-trade system of controlling greenhouse-gas emissions through 2030, lawmakers approved a Republican plan this week to put a constitutional amendment before voters that seeks to give the minority party more say over how the program’s money is spent. One-fourth of that money — more than $1 billion so far and $500 million projected a year in the future — goes toward high-speed rail, a project that Republicans widely oppose.

With the proposed $64 billion train line between Los Angeles and San Francisco facing not only Republican opposition but financial struggles, any cut in funding from the cap-and-trade program could be fatal.

“This absolutely calls into question the viability of high-speed rail going forward,” said Assemblyman Marc Steinorth, R-Rancho Cucamonga (San Bernardino County), who voted to extend cap and trade in part because of the proposed constitutional amendment. “If the bullet train can’t prove its worth, (this amendment) provides a pathway to ending the funding for the boondoggle once and for all.”

The logic to me is basically ridiculous. First, the constitutional amendment has to be passed by the voters, which is a big “if.” Second, the amendment won’t even affect any dollars until 2024, at which point the vote in the legislature would have to take place. And finally, even if a spending plan kills high speed rail, a simple majority vote of legislators after 2024 can change the spending priorities again.

The bottom line: the extension of cap-and-trade both shored up the existing cap-and-trade market through 2020 by increasing business confidence that the program is here to stay, and it gave the train line at least 4 additional years after 2020 to compete for funding under the program.

To be sure, there are still funding risks for high speed rail by relying on cap and trade. The legislature can try right away to tweak the funding formulas for how auction proceeds are spent, although this governor would likely veto any plan that diminishes funds for his priority project. And the amount of money from cap and trade may not be enough to finish the first section anyway from north of Bakersfield to San Jose.

Ultimately, the best bet for high speed rail is a new U.S. Congress that pays its share of federal dollars for the project, or a private investor to step up, which so far hasn’t happened. But the extension of cap and trade can only be seen as a positive at this point for high speed rail.

Last night the California Legislature scored a super-majority victory to extend the state’s signature cap-and-trade program through 2030. It was a rare bipartisan vote, although it leaned mostly on Democrats. My UCLA Law colleague Cara Horowitz has a nice rundown of the vote and its implications, as does my Berkeley Law colleague Eric Biber on the bill.

Lost in the politics is what this means for high speed rail. The system has a fixed and dwindling amount of federal and state funds at this point, and it’s relying on continued funding from the auction of allowances under cap-and-trade to build the first segment from Fresno to San Jose and San Francisco.

Lost in the politics is what this means for high speed rail. The system has a fixed and dwindling amount of federal and state funds at this point, and it’s relying on continued funding from the auction of allowances under cap-and-trade to build the first segment from Fresno to San Jose and San Francisco.

If the auction was declared invalid or ended at 2020 with depressed sales, the system would be in major jeopardy of collapsing before construction even finished on the first viable segment. Now it has some assurance of access to funds.

But of course it’s not that simple. The bill that passed yesterday has diminished available funds set aside for the programs that have been funded to date with cap-and-trade dollars. As part of the political compromises, more auction money will now go to certain carve-outs, like to backfill a now-canceled program for wildfire fees on rural development.

And another compromise may put a ballot measure before the voters, passage of which would require a two-thirds vote for any legislative spending plan for these funds going forward. That means Republicans — who generally hate high speed rail — would be empowered to veto future spending proposals.

Still, high speed rail once again has a lifeline, as do the other programs funded by cap-and-trade, such as transit improvements, weatherization, and affordable housing near transit. It’s an additional victory beyond the emissions reductions that will take place under this extended program.

The California Legislature may vote on reauthorizing California’s cap-and-trade program as soon as Monday. The program needs a two-thirds vote to inoculate the auction mechanism to distribute allowances from legal challenges, which is a heavy political lift that has required a lot of compromise and concession.

But in the midst of the debate, state legislators are lacking crucial data on the impact of the program to date on some of California’s most environmentally and economically disadvantaged regions, particularly the San Joaquin Valley and Inland Empire.

But in the midst of the debate, state legislators are lacking crucial data on the impact of the program to date on some of California’s most environmentally and economically disadvantaged regions, particularly the San Joaquin Valley and Inland Empire.

To fill that gap, CLEE and the UC Berkeley Labor Center teamed up earlier this year to release a report on the economic impacts of California’s major climate programs on the San Joaquin Valley. And using the same methodology and publicly available data, we are soon to release a follow-up report on the Inland Empire, both sponsored by Next 10.

But with the vote looming on cap and trade, we wanted to release our findings on the impact of cap and trade on the Inland Empire in particular, as well as summarize our previous findings from the Valley report. Our new op-ed in yesterday’s Daily Bulletin summarizes the data:

After accounting for the costs and loss of jobs in industries required to comply with cap and trade, as well as the benefits from investments of cap-and-trade revenue, we found in the Inland Empire, the program had net economic impacts of $25.7 million, $900,000 in tax revenue and net employment growth of 154 jobs.

These net benefits do not account for funds that have been appropriated but have not yet been spent. Since only about one third of appropriated funds have so far been spent on projects in these regions, the positive impacts will only grow. When we account for the expected benefits after all funds collected are reinvested in projects, the net economic benefit reaches nearly $123 million, with 945 jobs created and $5.5 million in additional tax revenue.

We found even greater net positive impacts in the San Joaquin Valley, totaling $202 million in economic activity, along with $4.7 million in state and local tax revenue. The program also created 1,612 net jobs in the Valley. When including expected benefits after all funds collected are reinvested in projects, this figure balloons to nearly $1.5 billion in economic benefits. These projects will create 7,400 total jobs, including more than 3,000 direct jobs in the San Joaquin Valley.

We hope this information will be useful to the public and to legislators as they decide on the program’s fate beyond 2020. I will post again on the report once it’s available for release.

California’s cap-and-trade program likely can’t survive in its current form after 2020 without a two-thirds vote of the legislature to reauthorize it. That’s because a central feature of the program involves auctioning allowances to pollute, which courts are likely to consider to be a “fee” that requires two-thirds approval of the legislature under 2010’s voter-approved Prop 26.

With that high hurdle, advocates have been scrambling to get the needed votes. Despite having a Democratic super-majority in both houses of the legislature, a number of key Democrats are opposed to (or at least skeptical of) cap and trade, because they fear the program allows polluters to continue polluting disproportionately in “environmental justice” communities — predominantly low-income communities of color.

So advocates have had to seek a bipartisan two-thirds solution, which requires oil-and-gas industry support. And that means major concessions to the fossil fuel industry.

But at the same time, the fossil fuel industry has lost leverage. The passage last year of SB 32, to extend the greenhouse gas reduction goals from 2020 to 2030, and AB 197, which allows for direct command-and-control regulation of polluting facilities, has put their back against the proverbial wall. And they recently lost their lawsuit challenging the legitimacy of the current auction mechanism. Industry would rather have the more “flexible” cap-and-trade system now, where they can seek reductions in the most economically efficient manner.

So there are some industry concessions and some environmental wins in the apparent consensus bills unveiled on Monday. First, AB 398 would officially extend the cap-and-trade program to 2030. In a big win for industry, the legislation would prevent local air districts in California from imposing their own limits on greenhouse gas emissions from sources already covered under cap and trade. As the San Francisco Chronicle describes, it would “effectively kill long-running efforts by Bay Area air quality regulators to place hard limits on emissions of carbon dioxide and other heat-trapping gases from local oil refineries.”

In another win for industry, the bill puts a ceiling on the price of allowances (permits to emit one metric ton of greenhouse gases under the cap). To date, allowance prices have typically hovered at or near the current price floor. Consider the ceiling a gift to industry by giving them a maximum penalty they’d have to face for polluting.

But in a concession from industry, the bill would reduce the use of “offsets” (projects outside of the capped facilities that help reduce greenhouse gases) and require that half of them occur in California or have a direct environmental impact on the state. The use of offsets weaken the sale of allowances by giving industry a cheaper out, so this is good news for the integrity of allowances.

Finally, the bill would prioritize the kind of state programs that could receive funding from the auction proceeds. The money must first go to efforts to control toxic air pollution from mobile or stationary sources like factories and refineries, second to low-carbon transportation projects, and third to sustainable agriculture programs.

This last provision is potentially a mixed bag on impacts, since it doesn’t necessarily track the highest emitting sources. But it may allow continued funding for high speed rail, which is on financial life support and at this point is only propped up by cap-and-trade proceeds. The governor doesn’t want to see the project die, which was part of his motivation for getting the auction reauthorized.

Meanwhile, AB 167 is a must-pass companion bill would require stricter air pollution monitoring around industrial facilities and tougher penalties for violating pollution regulations. This measure allows environmental justice advocates to claim some victory be securing the promise of direct emissions reductions from nearby polluters.

A number of environmental groups are not happy with the concessions, although the bill has received support from the likes of Environmental Defense Fund and tepidly from billionaire environmental activist Tom Steyer.

For my part, I think it’s an okay but not great deal. It’s probably worth continuing the state’s cap-and-trade program, if nothing else to try to prove the concept in case it can be workable in other states and nationally. And the auction proceeds provide some useful funding for everything from weatherization to transit to low-income housing.

Meanwhile, the state still retains a lot of authority over polluters via SB 32 and the state implementation of the Clean Air Act, and multiple complementary policies are still needed and remain in effect to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, such as the renewable energy, energy storage, energy efficiency, and electric vehicle mandates.

The vote could come as soon as Thursday, so stay tuned for the results.

UPDATE: The vote was just postponed to Monday, which could mean they’re having trouble getting the needed votes.

The California Chamber of Commerce has just lost its case against the state’s cap-and-trade auction, with the news from the Los Angeles Times that the California Supreme Court has refused to hear an appeal from the state appellate court. This means the auction mechanism in the cap-and-trade program is valid at least through 2020.

As we’ve covered on this blog before (most recently with Ann’s post from last fall, which links to our other posts), industry plaintiffs had argued that the auction represented a tax that required two-thirds approval of the legislature, under Proposition 13. But the auction isn’t like a tax, the courts have now consistently and definitively ruled, allowing the current mechanism to continue through 2020.

After 2020, the auction may be subject to a different legal analysis under 2010’s voter-approved Proposition 26, which legally converted many “fees” to taxes and therefore extended the reach of the two-thirds bar. AB 32, the law that authorized the cap-and-trade program, passed in 2006 and therefore wasn’t subject to Proposition 26, which came later. Since AB 32 authorized the program specifically through 2020, it can now continue at least through that year without needing two-thirds vote in the legislature or facing further court challenges.

This is a significant win for the state for two reasons: first, it allows the auction to continue, which is a crucial feature for distributing allowances to pollute under the cap. It holds businesses economically accountable for on-site emissions reductions, rather than allowing them to get allowances for free (although there may be other, more convoluted ways that they could purchase auctions and avoid court challenges). Perhaps more importantly from a political perspective, the auction generates proceeds for the state that have been used to fund everything from high speed rail to transit and weatherization for low-income households.

Second, it means industry loses a bit of leverage to shape cap-and-trade going forward in the legislature, which is debating proposals to extend the program now. The case has loomed in the background on these debates, with industry potentially wielding it as a negotiation piece to extract concessions, implicitly if not explicitly. Coming on the heels of the passage of SB 32 and AB 197 last year, which directed more command-and-control type approaches to emissions reductions at regulated facilities, it represents another loss of leverage for industry going forward.

Meanwhile, cap-and-trade post-2020 debates are heating up at the Capitol, with the governor determined to extend the system before the August auction and solidify the program’s place through 2030, in part to ensure a continued revenue stream for high speed rail. Industry is now on board as well (although they’re trying to weaken the program as much as they can), as they’ve lost their fall back option of killing the auction completely in court and simultaneously face much more draconian command-and-control regulation if cap and trade doesn’t continue.

It makes me wonder what might have happened had the Obama Administration chose to use the Clean Air Act more aggressively back in 2009, which (if successful in court) would have made cap-and-trade at the federal level similarly more appealing for industry.

We’ll never know. But in the meantime, we can watch the political dynamic play out at the state level here in California, with one less card for industry to play at the negotiating table, courtesy of the state Supreme Court.

With the passage of AB 197 yesterday, it’s easy to assume that the future of cap-and-trade may be gloomy beyond 2020. The program relies on legislative authorization via AB 32, which expires in 2020 (although arguably does not preclude extension beyond 2020). But AB 197 now specifically directs the California Air Resources Board to prioritize:

(a) Emission reduction rules and regulations that result in direct emission reductions at large stationary sources of greenhouse gas emissions sources and direct emission reductions from mobile sources.(b) Emission reduction rules and regulations that result in direct emission reductions from sources other than those specified in subdivision (a).

Ann Carlson at Legal Planet asks the question whether or not this spells the end of cap-and-trade. The answer may be quite complicated and will probably land the agency in court to resolve either way, as Ann discusses:

First, what does it mean to “prioritize” direct emission reductions? Does the language require ARB to impose such reductions? Or only consider them in conjunction with other considerations? What happens, for example, if direct emissions reductions are more expensive than reductions achieved through cap and trade even taking into account the social costs of emissions as required?

If the Air Resources Board leadership is committed to keeping cap-and-trade alive beyond 2020, which it appears they are, then my guess is they have enough wiggle room and deference to do so, once they undertake a proper analysis of the various options on any given issue before them.

But the new language in AB 197 will certainly provide fodder for cap-and-trade critics to take the agency to court over any decisions privileging that program over direct command-and-control approaches. So in that respect, AB 197 only adds further uncertainty to the program after 2020.

The issue does not not need to be solved right away, as cap-and-trade will continue through 2020. But the lingering doubts are apparently undermining the auctions for allowances, leading to low prices and uptake. And industry will not want to continue indefinitely with so much uncertainty in the short term. Hence their motivation to encourage a legislative fix as soon as possible.

2017 should be an interesting year for cap-and-trade.

As I blogged yesterday, the California Assembly took a giant step in approving SB 32 (Pavley), with one vote to spare for a majority. But the bill is tied to AB 197, which is up for debate today. That bill restricts some of the California Air Resources Board’s independence to implement the 2030 law by giving the legislature more oversight. It also adds in a requirement that all regulations under SB 32 must include a “social cost” accounting that could make command-and-control regulations more palatable than market-based solutions like cap-and-trade. My colleague Ann Carlson at UCLA Law has more analysis at Legal Planet.

The oil and gas industry has apparently targeted AB 197 as a way to bring down SB 32, plus the state senate will need to reconsider SB 32 given that the assembly amended it after it passed the senate first. So it could be another nail-biter.

But assuming these bills are approved in their current form, the implications for California’s post-2020 plans will become much more clear. First, most of the major climate regulations in place now will be able to continue through 2030, without the uncertainty of relying just on an executive order. The big exception is cap-and-trade. However, with command-and-control regulatory authority in place from SB 32, the oil and gas industry will have an incentive to try to re-authorize cap-and-trade as a more palatable alternative to direct regulation. That could make 2017 a big year for that program in the legislature.

In the end, cap-and-trade is just one means to achieving our state’s climate goals, and there are other ways to get there. Command-and-control may be more effective at guaranteeing actual emissions reductions. The downside is that this approach could entail greater costs for industry than a market-based program. And for environmentalists, these site-specific regulations don’t generate auction proceeds like cap-and-trade, which the state is now relying on to fund a host of programs, from high speed rail to low-income housing near transit.

But all of this speculation is premature, as we wait to see what the legislature does with AB 197. I’ll provide updates as the process moves forward.

As the Sacramento legislature debates SB 32 to formally extend the state’s greenhouse gas reduction targets to 2030, a big piece of the political puzzle is the cap-and-trade program. Namely, will the Air Resources Board have authority to continue the program beyond 2020?

There are a number of scenarios at play:

- The ideal situation, for boosters of the program, is that the legislature approves SB 32 with a two-thirds majority, which inoculates the program from any court challenges that it’s a “tax” or “fee” that requires a two-thirds vote under voter-approved amendments to the state’s constitution.

- Barring that (which seems unlikely this year but could happen next year if an anti-Trump “wave” sweeps away some of the legislators friendly to the oil and gas industry), the next option is to pass the 2030 goals with cap-and-trade via a majority vote. Arguably, the program is neither a tax or fee and therefore only requires a majority vote to enact. But a court would have to decide that outcome. So more uncertainty would result regardless.

- The third option is to simply carry on as usual under AB 32 authority, which the Air Resources Board is currently doing. As my colleague Cara Horowitz at UCLA Law has described, there is a pretty solid argument that AB 32 provides all the authority that the Air Resources Board needs to continue the program beyond 2020, particularly with Governor Brown’s executive order to that effect. But that approach too will almost certainly require a court to sanction, leading to more uncertainty in the coming years.

The final alternative, from a political standpoint, is to pass SB 32 on a majority vote, giving the Air Resources Board authority to issue command-and-control regulations to limit emissions from the oil and gas sectors. Presumably, the industry would much prefer a market-based approach to command-and-control, which would bring them back to the table with their legislative allies to re-authorize cap-and-trade beyond 2020. But who knows. And there’s also the wild card of the governor placing a 2018 ballot measure before the voters on the issue.

One thing for sure: if the legislature does not resolve the situation soon, it will likely fall to the courts to decide.

California has been reluctantly going it alone with cap-and-trade, ever since the proposed federal version died in the early days of the Obama Administration. While the state has done a good job (in my view) of developing rules that limit market manipulation and failure, the program is not without its flaws.

As state leaders consider extending the program beyond 2020, Severin Bornstein at the Energy Institute at Haas, UC Berkeley, argues, based on a paper he co-wrote, that the program suffers from lack of effectiveness:

Before committing to a post-2020 plan, however, policymakers must understand why the cap-and-trade program thus far has been a disappointment, yielding allowance prices at the administrative price floor and having little impact on total state GHG emissions. California’s price is a little below $13/ton, which translates to about 13 cents per gallon at the gas pump and raises electricity prices by less than one cent per kilowatt-hour.

While policy makers have argued that the low allowance prices just mean that other carbon-fighting programs must be successful, Bornstein begs to differ and offers some important recommendations:

So, can California’s cap-and-trade program be saved? Yes. But it will require moderating the view that there is one single emissions target that the state must hit. Instead, the program should be revised to have a price floor that is substantially higher than the current level, which is so low that it does not significantly change the behavior of emitters. And the program should have a credible price ceiling at a level that won’t trigger a political crisis. The current program has a small buffer of allowances that can be released at high prices, but would have still risked skyrocketing prices if California’s economy had experienced more robust growth.

The program is complicated and not nearly as elegant as a straightforward carbon tax would be. But it’s worth trying to get the details right, in case cap-and-trade can function as a viable alternative for tax-averse jurisdictions who want to decarbonize their economy. In that spirit, I hope Bornstein and his colleagues’ advice is well-taken by state leaders, as they work to improve the program.