California legislators are currently considering legislation (AB 813) to expand our grid across the western U.S., which would help integrate variable renewable energy more economically across a broader geographic region. However, the bill is hung up on disputes around labor and governance, as well as concerns that a regional grid will lengthen the lifespan of coal-fired power plants across the west.

But in the meantime, California’s grid operator has been operating a successful “energy imbalance market” in western states, as explained in this helpful video overview:

While a regional grid would be more effective, the energy imbalance market is helping to spur renewable production across the west. In turn that deployment means more industry support for renewables, even in conservative states.

Sammy Roth at The Desert Sun penned an engaging deep dive on the issues confronting California and the west if the state expands its grids into traditionally coal- and Republican-dominated states like Idaho and Wyoming.

Sammy Roth at The Desert Sun penned an engaging deep dive on the issues confronting California and the west if the state expands its grids into traditionally coal- and Republican-dominated states like Idaho and Wyoming.

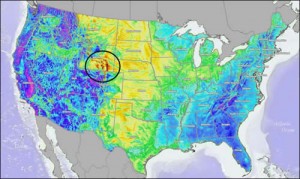

It’s an important issue, because as California produces more renewable energy than it can use locally, it will need markets to export that surplus. Similarly, the state will need to import surplus renewables (like wind from Wyoming and morning sun from Utah) when our wind and solar output is weak.

The upside for ratepayers is potentially huge savings (as Greentech media also described last December), while the upside for environmentalists is more renewable energy capacity without needing backup fossil fuel plants. And long term, more renewable development in these conservative states could change the politics there, as a domestic clean tech industry may lobby for more favorable policies.

But the expansion is held up by two factors: first, concern that grid expansion will throw a lifeline to out-of-state coal-fired plants that would otherwise get shuttered (environmentalists are split on whether that would happen, but California’s grid operator does anticipate a slight increase in greenhouse gas emissions from the plants in the short term, with significant long-term reductions); and second, disagreements over how grid governance would work across such diverse states:

“There’s not going to be any scenario where I would agree to a situation where the California Legislature is dictating policy to the state of Wyoming,” Matt Mead, Wyoming’s Republican governor, said in an interview. “Clearly, Wyoming is the No. 1 coal-producing state. It probably has a different perspective than California does.”

The mistrust cuts both ways. Officials in Idaho, Utah and Wyoming — deep-red states that rely on coal and other fossil fuels and don’t see climate action as a priority — don’t want to give coastal liberals too much power to decide which types of energy they use. Lawmakers in California, Oregon and Washington, but especially California, have the same concern about the red states.

If the governance issues cannot be solved, I wonder if a possible interim solution might be to focus on immediate grid expansion just to Oregon and Washington, given their similar politics and commitment to renewables. Then in future years it could expand to more fossil fuel-dependent states, once the market and governance kinks have been ironed out.

Meanwhile, the article is worth checking out just for the interactive map of every type of power plant in the entire U.S., including pumped storage facilities (I can’t reproduce it on my blog here but you can find it about 2/3 of the way down the article).

Supposedly the California legislature will debate grid expansion later this year, although I understand there’s a lot of skepticism from legislators, particularly about having California policies provide economic benefits out-of-state. But in the long term, it’s hard to see how California can achieve deep decarbonization in the electricity sector without this kind of regional approach.

A grid based largely on renewable energy will be tough to manage, given the intermittency of solar and wind power. That’s why it’s in California’s interest to expand its grid to cover the greater western United States. With a western market, California can sell cheap surplus renewables to other states and import their renewables when we don’t have enough.

A grid based largely on renewable energy will be tough to manage, given the intermittency of solar and wind power. That’s why it’s in California’s interest to expand its grid to cover the greater western United States. With a western market, California can sell cheap surplus renewables to other states and import their renewables when we don’t have enough.

To that end, California’s grid operator, the California Independent System Operator (CAISO) has proposed expanding to acquire PacifiCorp, a grid operator with transmission assets in five additional western states.

As I’ve discussed before, this expansion is not without controversy. PacifiCorp states are worried about losing sovereignty to a California-heavy expanded grid operator, while environmentalists are worried that the expansion will throw a lifeline to some coal-fired power plants in the PacifiCorp territory.

California officials are also worried that grid expansion could open up avenues for legal challenges and loss of sovereignty over the state’s domestic climate policies, particularly on renewable energy procurement. Specifically, would expansion increase the federal government’s ability to preempt state authority over domestic policies and energy contracts through the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC)? And would expansion open up California to legal challenges that claim that state policies in an expanded grid violate the commerce clause in the U.S. Constitution?

To evaluate these concerns, CAISO commissioned a legal analysis by UCLA Law’s Ann Carlson and University of Colorado Law’s William Boyd, in consultation with me and my Berkeley Law colleague Dan Farber. That analysis was released publicly yesterday afternoon, and you can read it here [PDF].

Here is what we found, in a nutshell:

The straightforward answers to each of these questions are that the inclusion of PacifiCorp assets in CAISO:

1) would not alter FERC’s jurisdiction and would not displace any existing state authority over environmental matters. CAISO is already subject to FERC jurisdiction and the inclusion of PacifiCorp in CAISO does not change this. FERC does not have jurisdiction over California’s energy and environmental policies and this would not change because of the inclusion of PacifiCorp in CAISO;

2) would not alter the constitutionality of California’s environmental and clean energy laws under the Commerce Clause of the United States Constitution because the policies are already subject to Commerce Clause scrutiny.

To be clear, this memo doesn’t address other potentially thorny issues, such as how the governance structures will be arranged in this future entity and how specific issues like the coal-fired power plant fleet might be treated. But it does provide assurance that expansion will not call into question California’s sovereignty over its clean energy policies, in terms of its constitutionality and ability to operate under federal jurisdiction.

In the battle to balance California’s booming renewable generation, the state’s grid operators are actively looking to expand into other states. The effort overall promises lower costs and a market for in-state surplus renewables to other states, while allowing California to access cheap renewables from other states when our in-state supply dwindles.

But local environmental groups don’t like the prospects of keeping Utah’s coal plants in business a little longer, while in-state power providers don’t like the potential loss of energy sovereignty to California. Utah leaders in particular are now sounding peeved, per the Salt Lake City Tribune:

Although the proposal says the body of state regulators would have “primary authority over regional … policy initiatives on topics within the general subject areas of transmission cost allocation and aspects of resource adequacy,” it’s not clear how or even whether the body would interact with the CAISO board. It’s also not clear what would happen to the five sitting CAISO board members when their current terms expire. Those details would be left to a transitional committee, which would be appointed by the CAISO board. This transitional committee would be tasked with hammering out the details not included in California’s governance proposal.

Though the proposal implies that the distribution of power would be worked out down the road, the initial setup worries Kelly Francone, executive director of the Utah Association of Energy Users.

Starting with a majority of board members representing California could lead to an imbalance of power down the road, she said.

States like Utah will be angling for more say over grid operations, while California will push back and will also be trying to ensure nobody messes with its renewable energy policies. If the expansion goes forward, the power sharing will be dependent on the negotiating skills of the respective parties, leaving much of the arrangement’s governance details up in the air for now.

As California and other states zoom toward getting 50% of their energy from renewable resources like solar and wind, there’s no question that we’ll need a bigger geographic grid footprint to balance these sources. We can’t rely solely on these in-state, intermittent resources without driving up rates and firing up backup fossil plants to compensate for their variable production.

An expanded grid addresses that problem (along with energy storage and demand response) and provides economic benefits to boot. It means, for example, that California can sell its excess surplus power in the spring and fall to other states, while we can import solar from Arizona in the morning or wind from Wyoming at other times.

That’s why California’s grid operator — the Independent System Operator (CAISO) — is so gung ho on purchasing the neighboring PacifiCorp, which operates in six western states. As Utility Dive reports, CAISO’s CEO is bullish about the opportunities, both to save ratepayers money and to clean the grid.

But the politics are messy. Here in California, as E&E reports [subscription required] the Sierra Club in particular is concerned that the merger of these two grid operators will give a bunch of coal plants in the PacifiCorp portfolio a new market to access and therefore a longer lease on life. NRDC counters that any bump in emissions will be short-term and that the merger will ultimately greatly reduce emissions.

Meanwhile, in the states subject to the merger, the opposition is not from environmental groups but from the in-state generators that risk being displaced by cheap out-of-state renewables. After all, it’s hard for them to compete with surplus solar power from California that is coming to the state for cheap, displacing coal and gas-fired power in the process. These states also fear a loss of control over the grid operators, as the governing boards are likely to be dominated by California appointees.

All in all, it’s a tough political situation but one that shouldn’t be insurmountable, with the right compromises — particularly given how much ratepayers can benefit from the merger and how crucial an expanded grid footprint is to deep decarbonization of the electricity supply.

This legislative season in California will rank as a big disappointment for environmentalists. The last-minute failure to secure a 50% petroleum reduction by 2030 goal, followed by the defeat (actually postponing) of the bill to set 2030 and 2050 greenhouse gas reduction targets, was a major blow for environmentalists used to getting what they want out of Sacramento. Many commentators are starting to blame Governor Jerry “above the fray” Brown for not doing more to secure passage in the Assembly.

But lost in these setbacks is the major accomplishment of boosting California’s renewable energy standard to 50% by 2030, coupled with a mandate to double energy efficiency in existing buildings by that year. SB 350 (De Leon) may have been stripped of the petroleum goals, but these other targets are significant accomplishments. The energy efficiency piece set forth a process for the California Energy Commission to set long-term targets and evaluate progress on a regular basis, while the renewable energy mandate essentially just adds the 50% goal into the previous legislation requiring 33% by 2020 — in other words, no new process needs to be created for California to continue down this renewable path.

But lost in these setbacks is the major accomplishment of boosting California’s renewable energy standard to 50% by 2030, coupled with a mandate to double energy efficiency in existing buildings by that year. SB 350 (De Leon) may have been stripped of the petroleum goals, but these other targets are significant accomplishments. The energy efficiency piece set forth a process for the California Energy Commission to set long-term targets and evaluate progress on a regular basis, while the renewable energy mandate essentially just adds the 50% goal into the previous legislation requiring 33% by 2020 — in other words, no new process needs to be created for California to continue down this renewable path.

And finally, SB 350 makes it easier for California to develop a western regional market for renewables that will cover neighboring states and allow California both to import renewables from out-of-state when we need them and export our surplus renewables to other states. The legislation allows the California Independent System Operator, which essentially manages California’s grid, to change its governing rules to allow regional transmission operators to become part of the system. That will facilitate the import and export of renewables, helping California to better balance our in-state supply and ensure that dips in production don’t result in more natural gas-fired power.

So while the legislative season may have largely ended in disappointment, the accomplishments that did occur are worth celebrating for environmentalists.

With more solar panels, internet connected home appliances, electric vehicles, and small-scale batteries, California will soon have millions of “distributed” energy resources it can tap into to make the grid more efficient and clean. The entity in charge of managing the grid just made it much easier to connect and aggregate these items as a bulk resource:

With more solar panels, internet connected home appliances, electric vehicles, and small-scale batteries, California will soon have millions of “distributed” energy resources it can tap into to make the grid more efficient and clean. The entity in charge of managing the grid just made it much easier to connect and aggregate these items as a bulk resource:

California is already busy creating new regulations and market structures to integrate rooftop solar, behind-the-meter batteries, plug-in electric vehicles and fast-acting demand response systems into its grid. This week, California’s grid operator took another step down this path — one that could allow these resources to tap the state’s grid markets as a revenue-generating resource, possibly as early as next year.

On Wednesday, the California Independent System Operator (CAISO) published a proposal (PDF) for creating a new class of grid market players, known as distributed energy resource providers — DERPs for short. In simple terms, the proposal sets rules for how DERs can be aggregated and dispatched to serve the same grid markets open to utility-scale energy installations today.

As the rules roll out and get refined, the state will become an international leader on integrating these resources into the grid, while providing owners of these assets with an additional revenue stream — further encouraging their deployment.