You get a double shot of me on KALW today. This morning at 10am PT, I’ll guest host Your Call’s One Planet Series, when we’ll discuss what it will take to electrify the US economy with clean energy. How feasible will this be, and what will it cost? Joining us will be:

- David Reichmuth, senior engineer in the Clean Transportation program at the Union of Concerned Scientists.

- Ari Matusiak, chief executive of Rewiring America, a leading electrification nonprofit working to electrify our homes, businesses and communities.

Later in the program, we’ll have a conversation with award wining filmmaker Katja Esson about her new documentary RAZING LIBERTY SQUARE, about a public housing project in Miami for Black residents during a time of legal segregation (preview above). The city is ground-zero for sea-level-rise, and when residents learned about a $300 million revitalization project in 2015, they knew that their neighborhood is desirable because it is located on the highest-and-driest ground in the city. Some of them prepared to fight a new form of racial injustice called Climate Gentrification, which Esson followed for the film.

Then at 6pm PT on State of the Bay, I’ll talk with Kate Harris, Berkeley city councilmember and author of the 2019 ordinance banning natural gas in new construction. A panel of judges on the US court of appeals has just reversed that ban. What does this mean for our environment and what will lawmakers do next?

Then we’ll cover how the pandemic has decimated transit ridership, causing California’s transit agencies to face major funding shortfalls just as federal Covid relief funds are due to expire. We’ll talk with Laura Tolkoff, Transportation Policy Director for SPUR, and Rebecca Saltzman, Bay Area Rapid Transit director for district 3, about what agencies are doing to avoid falling off this fiscal cliff.

Finally, we’ll continue our series ” Have you met?”…. we’ll meet teacher and comedian, Chris Corrigan as he reflects on the ever changing Bay Area.

Tune in at 91.7 FM in the San Francisco Bay Area or stream live at 10am PT for Your Call and then again at 6pm PT for State of the Bay. What comments or questions do you have for our guests? Call 866-798-TALK to join the conversation!

The San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) system provides the crucial transit backbone for one of the most economically dynamic metropolitan regions in the world. But as Michael C. Healy writes in his book BART: The Dramatic History of the Bay Area Rapid Transit System (Heyday Books, 2016), it almost never came to be. In fact, just as I documented about the Los Angeles Metro Rail history in my 2014 book Railtown, BART’s future came down to one swing vote in 1962 on a county board of supervisors (in Los Angeles, it was one switched vote in 1980 on that county’s transit board).

That swing vote, from the farmland of eastern Contra Costa County, was never supposed to matter. Back in the early 1960s, BART was going to be a six-county project, funded by a multi-county bond measure. But rural Santa Clara County (in today’s Silicon Valley) dropped out due to local anti-tax sentiment and a sense among elected officials that they wouldn’t get their money’s worth from a San Francisco- and Oakland-based system.

Next, neighboring San Mateo County dropped out, due to concern they would lose local sales tax revenue from in-county shoppers who would instead take BART for better retail north in San Francisco. And residents there were also generally satisfied with their existing Caltrain connection to the City.

The loss of those two counties meant that Marin County across the Golden Gate to the north of San Francisco would have to drop out, because without the South Bay counties, the tax base to fund the construction would be too small to cover the expense of getting a train across the bay to Marin.

So it was down to three counties to go forward with a viable, but scaled-down bond issue to fund the system: San Francisco, Alameda (home of Oakland and Berkeley), and the largely suburban and rural Contra Costa.

But Contra Costa County supervisors were divided. The train’s backers had two votes on the five-member board locked down, but two supervisors already opposed. That left Supervisor Joe Silva as the swing vote from the eastern farmtown of Brentwood. Silva was undecided. But last-minute lobbying by then-San Francisco mayor George Christopher and Oakland mayor John Houlihan, culminating in a 5am breakfast meeting at a Martinez coffee shop, sealed the deal. Silva was a yes.

That ensuing 1962 bond measure was pivotal to launching BART. The legislature had recently dropped the voter-approval threshold to 60%, and the measure barely squeaked by. In fact, Silva’s Contra Costa County voters did not meet that threshold, but the numbers were averaged with Alameda and San Francisco counties to achieve 61% approval.

Healy tells these and other stories about the system in an engaging, first-hand way. For not only is he a scholar of the system, he was also the head of public relations at BART for many years. As a plus, that means he was close to the system’s key leaders and part of some big decisions, which he can relay in the story with authority. It also means the book focuses a disproportionate amount on scandals big and small, as well as marketing efforts, as that was Healy’s bailiwick in his job at BART.

But on the downside, Healy’s close role and vested interest in the system means he often casts an uncritical eye toward the flaws. For example, he never addresses the failures of ridership compared to initial projections, except to put a positive spin on them. And he never engages with debates about more cost-effective alternatives to heavy rail that might have served more residents more quickly and cheaply. He also fails to acknowledge how some of the system’s recent extensions to low-density suburbs have cannibalized the quality and condition of the core system and led to the deterioration we see on it today.

Still, the book is useful for fans of BART, providing some interesting tidbits:

- While talk of building a rail system to cross the bay had gone on for much of the early twentieth century, the system started in earnest with planning in the 1950s, following an Army-Navy study that indicated that a bay crossing for rail made most sense.

- San Francisco Supervisor Marvin Lewis was a crucial early booster, getting Bay Area Council business leaders to lobby Sacramento legislators to authorize a commission and bond capability for the 1962 ballot.

- Once the system was under construction, it could take advantage of freeway rights-of-way that were also under construction, to provide cheap and ready-made (though not friendly to rail-oriented neighborhoods) rights-of-way.

- The system was meant to pioneer new ‘space age’ automated train technology, per the vision of early general manager Billy Richard (B.R.) Stokes. But as costs kept rising, voters needed to keep approving new funding measures to get the system completed, while the automated technology faced multiple technical challenges.

- When the City of Berkeley objected to loud, unsightly elevated rail tracks through its jurisdiction, the BART board forced them to pay the cost of undergrounding it, which is why the system goes underground at the Oakland border and then surfaces again in Albany and Richmond. Today, most cities have the legal and political leverage to force BART (and other similar transit districts) to pay for those kind of improvements.

- A Downtown Oakland retailer close to the mayor forced the train tunnel to go around his parcel under the city, in order to avoid surface disruption at his store. But he promptly went out of business before the system opened, so now BART riders are subjected to a slow squeaky turn under Oakland for the rest of their lives for nothing.

- The Bay tube was built by construction crews carefully sinking pre-fabricated concrete tunnel blocks onto a gravel bed laid directly on the bay mud floor and then welded together to seal them from the water.

Overall, I would recommend the book for anyone interested in BART and the history of rail systems more generally. Although while it’s chock full of anecdotes, the narrative does tend to jump around without much focused organization, making it sometimes hard to read in long batches.

The lessons of BART’s history should be familiar to anyone who’s followed rail transit deployment more generally in the U.S.: the costs, performance and construction timelines are always worse than advertised, but residents often like and rely upon what gets built. And to build something at the scale of BART took a lot of vision and frequent financial support from voters. Simply put, it’s hard to imagine the Bay Area today without BART.

San Francisco’s BART rail transit system is an integral part of the Bay Area’s transportation infrastructure. But BART has recently experienced an overall ridership decrease and faced challenges maintaining reliability while juggling key expansion plans.

To explore BART’s past, present and future, KABC7- television is running a weeklong series on the system. For the segment on the history of BART, they interviewed me and former State Senator Quentin Kopp. We described some of the early challenges with getting the system built, as well as the opportunities to improve development around the stations and build a second crossing between Oakland and San Francisco.

Watch the video above and read more here. I’ll have more to post soon on this history — stay tuned!

It was a landmark decision last week. For the first time in Bay Area history — if not nationwide — a rail transit agency decided not to build more rail. And it was a smart decision that will benefit rail transit going forward.

As I blogged about, the BART extension to outlying Livermore would have been costly and attracted just a few riders. It also would have pulled resources away from the core system, exacerbating its reliability problems. Instead, a bus rapid transit line would deliver all the benefits of BART at a fraction of the cost and build time.

In recognition of the fiscal pressures, BART’s elected board made the sensible — and one-vote margin — call last week to ditch the gold-plated option. Unfortunately, Livermore officials don’t want the bus rapid transit line as an alternative, as they apparently hold out hope that some other agency will build the BART extension (an idea that has precedence but would still be irresponsible). So for now they’re left with nothing.

But rail proponents should recognize that heavy-rail options like BART are only suitable for high-density areas. Bus rapid transit may not sound as nice to the public at first glance, but it can be a high performer in practice.

As if on cue, BART opened the same week a new “mini BART” line to exurban Antioch, using cheaper biodiesel-powered trains as a cost-savings and right-sizing measure. While not bus rapid transit, it’s a recognition of the fiscal and ridership realities of serving the low-density region with mass transit.

Meanwhile, here were the votes on the Livermore proposal:

Against the extension:

Bevan Dufty

Nick Josefowitz

Rebecca Saltzman

Lateefah Simon

Robert Raburn

For the extension:

John McPartland

Debora Allen

Joel Keller

Tom Blalock

Congratulations to the BART board on a smart move, and to all BART riders who care about the system’s long-term sustainability.

Tonight the BART board of directors will be deciding on whether to break the bank on a costly, low-ridership heavy rail extension to Livermore or go with a much more cost-effective bus rapid transit option. At issue is what do to extend the system 5.5 miles on the Dublin-Pleasanton line to the historically suburban Livermore.

The gold-plated heavy rail option is estimated to cost $1.6 billion, with about $500 million already committed, and scheduled to take 10-15 years to build. Meanwhile, all that money and time would benefit just 13,400 riders per day by 2040, despite plans for new office and housing developments near the future station.

A much better option would be to extend a bus rapid transit line in a separate right-of-way. As BART director Nick Josefowitz points out in a compelling op-ed today in the San Francisco Chronicle:

The good news is that there is a more cost-effective transportation project on the table that would deliver equivalent travel times for Livermore residents and cost less than one-quarter of the extension proposal. Express buses initially would run from the Dublin-Pleasanton BART station along the recently built I-580 express lanes to downtown Livermore, the Livermore national laboratories, Las Positas College and elsewhere.

The express-bus project could be paid for out of existing funds and require no new taxes. Extension advocates may argue that Livermore has been paying taxes to BART since 1959 and is entitled to a station, but the total Livermore has paid to the BART system over that period (adjusting for inflation) is $436 million — not nearly enough to fund the extension. The express-bus project is fully funded. Construction could start quickly and deliver immediate relief.

Josefowitz’s vision for the Bay Area is sensible: a ring of express buses traveling on dedicated rights-of-way, providing fast, convenient, and cheap transit service to beat traffic. Otherwise, there simply isn’t enough money to build and subsidize heavy rail to all corners of the region.

Ultimately, the real problem here is that decisions like these are left to elected directors on the BART board. What BART (and all transit agencies) needs is rigorous performance standards to ensure that expensive heavy-rail investments are never an option for low-ridership projects. These performance standards would weed out bad projects based on ridership and other key metrics before they’d even get to the board in the first place.

But until those standards are in place, we’ll have to hope the board makes the right call tonight.

Of all the new housing bills in California this year, perhaps the most interesting is a relatively small-scale proposal by San Francisco’s Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) that could become a statewide model. AB 2923 (Chiu) would essentially allow BART to adopt local zoning standards for land it owns within one-half mile of an existing or planned BART station entrance.

The problem the bill is trying to solve is that many BART-owned parcels near the stations are wastes of space. They’re typically surface parking lots, which is a highly inefficient use for high-value land near BART. Adding underground parking (if any) and building housing and offices above would generate more riders per square foot and therefore reduce the taxpayer subsidies required to operate BART.

There are added benefits to this kind of BART parcel development. More offices in “reverse commute” areas on the BART system would help offset the peak ridership crush, as more workers could travel in the less-crowded direction. And more BART development could help spur building on surrounding parcels by bringing in more residents and workers and therefore more demand for nearby services and housing.

But this development won’t happen on its own. In many cases, local governments with land use control over the station areas restrict this development from happening. Hence the need for BART to propose this bill.

AB 2923 would start by spurring the elected BART board leaders to adopt transit-oriented development (TOD) guidelines by a majority vote. The guidelines must establish minimum local zoning requirements for BART-owned land on any contiguous parcels larger than one-quarter acres, within one-half mile a station entrance.

This step by itself is not a big deal, as BART already has TOD guidelines in place for many stations. The real kicker is that AB 2923 would then require local jurisdictions to adopt an ordinance that incorporates the TOD zoning standards within two years from when they were approved by BART.

In some ways, the bill is not that big of a deal. Since it only affects BART-owned land, most station area parcels are unaffected (in some station areas, BART doesn’t even own any land).

But in other ways, it would mark an important step by giving a transit agency land use control over their own parcels. If it works, it could become a model for transit agencies across the state. Since the success of a transit system ultimately depends on supportive land use, for too long these agencies have been at the mercy of local governments that are unwilling to commit to dense development near the stations. Now, under AB 2923, they would finally have some control over their destiny. It would be a win for the agencies — and for taxpayers and system riders.

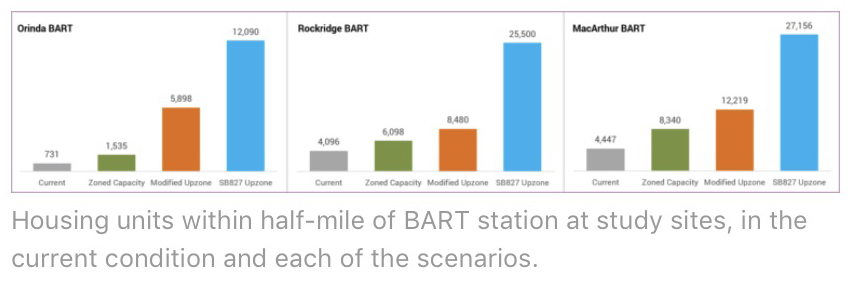

Joe DiStefano at the Urban Footprint blog ran a useful experiment to see how the transit-oriented upzoning proposed in SB 827 would affect three station neighborhoods in the San Francisco Bay Area’s BART system. All three stations are in the East Bay but are somewhat distinct:

- Orinda is a low-density suburban commercial and residential stop

- Rockridge is a medium-density, largely suburban stop

- MacArthur is a more urbanized commercial stop

The analysis included an assessment of what housing units are currently built in the 1/2 mile radius of the stop, how much capacity would be legal to build under current zoning, what would happen if only commercial areas were rezoned and not single-family homes and townhomes, and what would happen if the full upzoning allowed under SB 827 took place.

Here are the results (apologies for the blurry screengrab — check out the site for a better image):

The bottom line is that under SB 827, potentially 48,000 additional new units could be built, just within 1/2 mile of these 3 station areas. It demonstrates the power of upzoning near transit to build enough housing to accommodate future population growth and stabilize prices for existing residents.

The bottom line is that under SB 827, potentially 48,000 additional new units could be built, just within 1/2 mile of these 3 station areas. It demonstrates the power of upzoning near transit to build enough housing to accommodate future population growth and stabilize prices for existing residents.

And even if single-family homes and townhomes didn’t redevelop (either because the owners didn’t sell or the bill eventually gets amended to prevent development there), the state could still see over 10,000 new units in the “modified upzone” scenario — again, just at 3 station neighborhoods.

Caveats are of course necessary: not all of these units would be built, even under the full scenario. Property owners wouldn’t sell in some cases, developers wouldn’t maximize density and height on all lots, other local restrictions may prevent some of the units from getting built, and the final bill may contain additional restrictions that would limit a full build-out.

But this analysis indicates the power of upzoning near transit to help solve California’s dire housing shortage. Given the importance of this issue to California’s environmental and economic health, solutions like SB 827 are well in order, as this analysis shows.

Election night took a turn to the hard right at the national level. But here in California, the results were all about the progressives. The California legislature appears to have failed to achieve a 2/3 supermajority of Democrats in the legislature, although some races are still being counted. However, as KPCC radio reported, the Democrats did get major pickups and are ready to move forward on a progressive agenda.

Among the state ballot initiatives, the big ones for the environment included:

- A yes vote to legalize marijuana with Proposition 64, which could finally bring illegal grow operations under environmental regulations (although it’s unclear if federal environmental laws would pertain, or if grow operations overall would increase in otherwise non-agricultural areas); and

- A no vote on Proposition 53, which would have made high speed rail in particular more difficult to build by requiring voter approval on all new revenue bonds.

Perhaps more importantly, votes at the local level were huge on land use and transportation. The big ones, as I laid out on Tuesday:

- Measure M in Los Angeles passed with almost 70% approval. This puts the region on a dominant leadership path on transit, with $120 billion now slated to improve transportation in the region.

- Measure RR in the Bay Area passed the two-thirds hurdle, meaning BART will be revamped and improved for faster service — and also study of a possible second tube under the Bay.

- Measure LV in Santa Monica went down, meaning NIMBY politics won’t play in the seaside community, and also potentially foreshadowing failure on a city-wide initiative that anti-housing groups are planning.

And around the country, transit measures seemed to be doing well. Voters in Seattle apparently approved funding for a 62-mile rail extension, while Atlanta approved more light rail funding.

So on an otherwise dark night for progressive causes around the country, cities and states are still leading the way.

A real estate firm did a quantitative analysis for the San Francisco Bay Area:

Estately Real Estate Search analyzed the last six months of home sales for houses, townhouses, and condos that were within a one-mile radius of each BART and Caltrain transit stop. We then broke them down by price per square foot.

At an average of $1,630 per square foot, Caltrain’s California Avenue stop in Palo Alto is the Bay Area’s most expensive transit stop to buy a home near. Pittsburg/Bay Point BART stop, the furthest from downtown San Francisco, is the least expensive at $219 per square foot on average.

Here is the map:

It would be interesting to see how these values compare to home prices outside of that one-mile radius. In other words, is there a price premium for living near these transit nodes? Some studies have documented this transit-oriented value, such as this one [PDF] from APTA, Center for Neighborhood Technologies, and the National Association of Realtors in 2013. But this Estately study could be expanded to show the trend in the Bay Area. Otherwise, it’s hard to know how much rail transit impacts the prices.

It would be interesting to see how these values compare to home prices outside of that one-mile radius. In other words, is there a price premium for living near these transit nodes? Some studies have documented this transit-oriented value, such as this one [PDF] from APTA, Center for Neighborhood Technologies, and the National Association of Realtors in 2013. But this Estately study could be expanded to show the trend in the Bay Area. Otherwise, it’s hard to know how much rail transit impacts the prices.

Meanwhile, this study is a nice complement to the UC Berkeley Law and Next 10 report released last October that grades rail transit station neighborhoods in California, including in the BART and MUNI systems.

While Los Angeles transportation leaders just unveiled a $120 billion plan for the November ballot, BART leaders in the Bay Area are similarly hoping for electoral gold with a bond measure for the same election. BART is in a state of rapid decay and would use the bond funds primarily to do long-neglected maintenance.

But union politics may hinder the chance to get a two-thirds voter supermajority on the measure. After the crippling 2013 BART strikes brought the region to a halt, then-suburban Orinda city council member and Democrat Steve Glazer was the only elected official willing to speak out against the powerful public sector unions backing the strike.

Ruling Democrats fled from Glazer en masse, but he rode East Bay suburban frustration with BART all the way to the State Senate in a special election in 2015, with strong support from the business community and Republicans.

Glazer has held firm to his anti-BART union stance, even holding up comprehensive state transportation reforms unless he gets concessions on BART labor policies. And recently he threatened to withhold support for the BART bond unless the agency undertakes labor reforms.

But he may now be alienating his big business backers in the Bay Area, who’d rather see the BART bond pass to get their workforce reliably from the suburbs to employment in the city — even if it means passing an opportunity to get concessions on labor practices. The business group Bay Area Council came out strongly against Glazer’s position in a recent newsletter:

The Council wholeheartedly agrees that BART needs to do a much better job of managing costs, but strongly disagrees that risking the success of a measure designed to ensure the safety and reliability of an aging system serving 440,000 riders every day is the responsible approach. The Council was on the front lines three years ago opposing BART strikes and advocating for prioritizing the system’s desperate infrastructure needs. Addressing BART’s labor agreement should be handled separately when it expires in 2017. As the BART Board of Directors eyes a decision in the coming months on whether to move ahead with the ballot measure, the Council is urging Sen. Glazer and other elected leaders to support a measure that puts the system’s future safety and reliability first.

It’s a rare break with the business-friendly Glazer — and a sign of how tight the electoral margin is likely to be in November for BART.

But Glazer is desperate to use whatever leverage he has. Given the role public sector unions play in supporting Democratic politicians in the Bay Area and statewide, he’s on the wrong side of a lopsided battle.