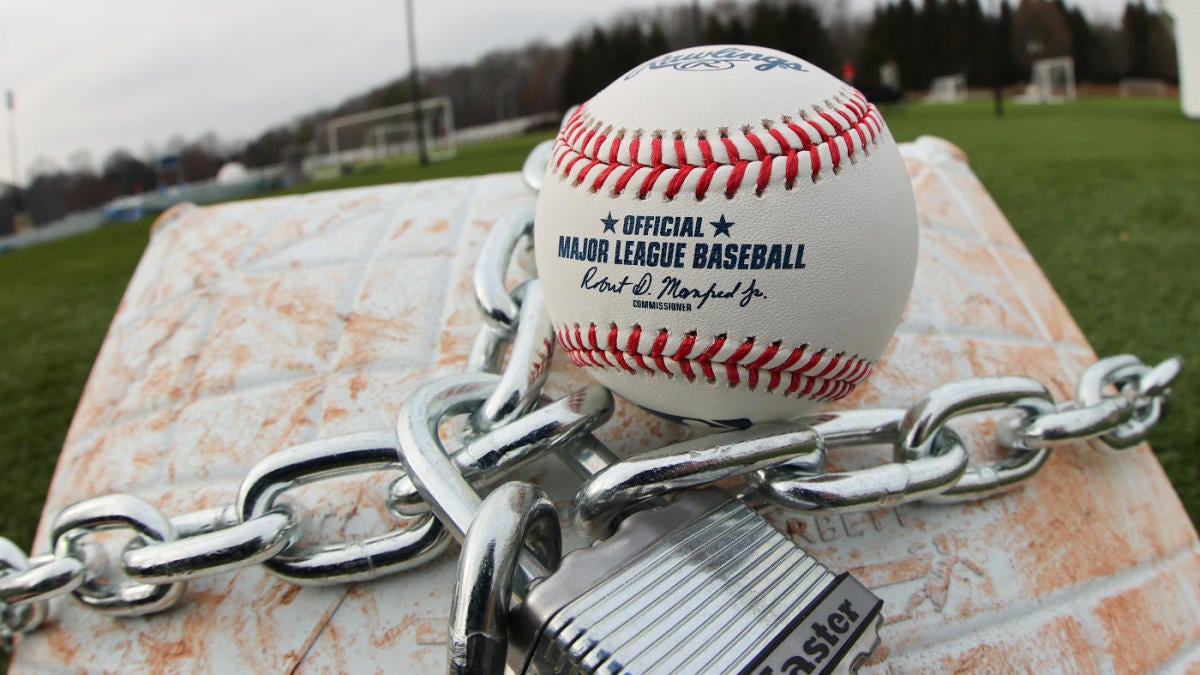

Major League Baseball just announced that the season will be delayed, due to an owner lockout. And most Americans just shrug. The sad fact is that the sport that used to be America’s pastime has seen audience interest decline significantly over the past few decades.

The signs are everywhere: ticket sales have been declining for two decades, and even the World Series hardly draws an audience (viewership declined from 20% of Americans in the 1970s to just 3 percent by 2020). The fanbase is also older and whiter, with an average age now 57, up from 52 less than twenty years ago, with hemorrhaged appeal to Black Americans in particular.

And it’s all the fault of my hometown team: the Oakland A’s. The A’s are the team that pioneered how to hack the rules of the game using then-emerging big data tools, made famous in the 2002 Michael Lewis book Moneyball. The result has been a far slower, less dynamic, and boring game.

As the New York Times detailed, last season saw the longest average game time in history (3 hours 11 minutes), along with the most pitchers used per team (4.43 per game, tied with 2020). Worse, it now takes an average of four minutes between balls put in play. Meanwhile, teams averaged nearly nine strikeouts per game, while stolen bases (0.46 per game) have decreased to a 50-year low.

This is not the way the game was originally played, or even how the game is played in Little League through high school still today.

So what happened? In short, the game has been hacked by Big Data, led by the A’s.

Using complex data formulas, teams have figured out optimal pitching matchups for virtually every batter, leading to relentless and time-consuming pitching changes. Pitchers are now coached and conditioned to throw faster and hit specific, computer-prompted spots, leading to injuries and more strikeouts.

Hitters meanwhile use complex computer analyses of swings to focus on “launch angles” to maximize home runs, even as strikeouts skyrocket. And nobody steals bases anymore, as the data show that is inefficient to do.

Defensively, teams have used algorithms to determine the optimal “shift,” stacking all fielders in the area where hitters are most likely to hit. As a result, screaming liners that use to go for base hits or doubles instead disappear regularly into well-positioned mitts in shallow left or right field.

In short, all the things fans come to see and love about the game are gone: the crack of the bat, great defensive plays, cat-and-mouse games on the basepaths, and dominating pitching performances. Games drag on with little action other than walks and home runs.

And the decline of the game is only going to get worse, due to the rise of other entertainment options like video games, as well as demographic change in the United States that might favor other sports like soccer (interestingly, sports like football and basketball don’t seem to have a worse product due to big data, perhaps due to the contrast with baseball’s more precision-based style of play).

So how can the game fix itself? The current proposals are designed to triage the problems. There’s talk of banning the defensive shift, moving the pitchers mound back to give hitters more time to swing, forcing a pitcher to stay on the mound for a minimum number of batters, and limiting the time between pitches or batting changes, among others.

But these are just cosmetic changes chasing the data revolution. They don’t get to the heart of the problem. Instead, there’s one fix that could solve much of the problem plaguing baseball.

It’s simple: expand the strike zone, and do so dramatically.

With a bigger strike zone, hitters couldn’t be so selective, waiting on a “meat” pitch to belt or trying to work a walk. They would have to put the bat on the ball, generating action, movement, and defensive plays. They also would be less likely to hit into the defensive shift, as they’d have to be more agile to hit pitches farther out of their comfort zone.

That increased hitting would in turn reduce pitch counts and the need for time-wasting pitching changes. In short, you’d see more defense, more action, and shorter games. That’s the game that many of us came to love as children, including me when I fell in love with the Oakland A’s back in the 1980s.

I’m sure there are myriad reasons this change would be tough to implement. Players might push back. Owners may balk.

But unless something drastic is done, the national pastime risks fading into obscurity. Like any failing industry or business, a revamp is needed. Expand the strike zone, or watch the sport wither like many others before it.