The climate fight should ultimately benefit all communities, just as they are all part of the solution. Agricultural communities are no exception.

Farmers and ranchers can implement climate-friendly techniques that both sequester carbon and boost profits and long-term sustainability (sometimes referred to as “regenerative agriculture”). Examples of these practices include crop diversification and rotation, cover cropping, low-to-no tillage, rangeland and cropland composting, and reduced chemical inputs. Beyond carbon capture, these techniques and the principles that underlie them can lead to improved soil quality, higher long-term yields and greater yield stability, and resilience to drought, floods, disease, and pests.

Yet financial, logistical and resource barriers stand in the way of greater adoption. To address these challenges, UC Berkeley Law’s Center for Law, Energy & the Environment (CLEE) partnered with the Berkeley Food Institute to convene farmers, policy experts, advocates, investors, and other stakeholders in the farming community for a virtual roundtable on public-private solutions.

The group’s recommendations were captured in a new report released last month, Redefining Value and Risk in Agriculture: Policy and Investment Solutions to Scale the Transition to Regenerative Agriculture. Highlight solutions include:

- Develop a More Robust Research Base: Research institutions should advance the scientific case for regenerative agriculture and standardize measurement protocols

- Reform Crop Insurance: Congress and the US Department of Agriculture’s Risk Management: Agency should reform crop insurance to reflect the risk reduction benefits associated with regenerative practices

- Redefine Risk: Federal and state governments, banks and investors should account for the risk reduction benefits of regenerative practices and reflect those benefits in financing and direct payments

- Advance State-Level Policies: State governments should expand investments in effective existing policies like incentive programs and peer-to-peer support network initiatives

- Prioritize Equity in Agricultural Policies: Government at all levels should develop more integrated and equitable systems to serve farmers, such as streamlined technology platforms and more robust technical assistance

- Urge Landowners and Supply Chain Actors to Enable Regenerative Production: Landowners and supply chains should help promote regenerative farming among tenants and farmers by incorporating flexibility into contracts and removing barriers

Widespread implementation of these solutions could help in multiple ways, from reducing greenhouse gas emissions and other pollution, improving economic conditions in farming communities, and addressing inequalities between rural and urban areas. To learn more, you can download the report here.

New Berkeley/UCLA Law report discusses policy solutions to boost engineered carbon removal technologies. Register for a free webinar on Wednesday, January 27th at 10am with an expert panel to hear about the top findings.

California has enacted ambitious climate goals, including a statewide carbon neutrality target by 2045. While much of the required greenhouse gas reductions will come from clean technology and emission reduction programs, meeting these targets will necessitate new methods of actively removing carbon from the atmosphere and capturing difficult-to-mitigate industrial facility emissions, including via technologies broadly known as engineered carbon removal.

These processes include carbon capture and sequestration of industrial facility emissions, biomass energy production with carbon capture, and direct air capture of atmospheric carbon. They can complement traditional emission reduction and nature-based solutions but are mostly still in the early development stages. Proponents of these projects face significant questions about carbon removal capacity, duration of sequestration, optimal locations, support infrastructure, and long-term financing.

Capturing Opportunity: Law and Policy Solutions to Accelerate Engineered Carbon Removal in California offers a suite of policy innovations and proposals to address these challenges, including:

- Establishing a statewide single point of contact for engineered carbon removal project incentives, permitting, and oversight.

- Identifying project and infrastructure corridors best suited for new development to conduct pre-permitting environmental, land use, and community review.

- Developing environmental review guidelines specific to carbon removal projects.

- Considering extension of and adjustment to the state’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard‘s carbon capture protocol to support project financing.

The report is sponsored by Bank of America and informed by an expert stakeholder convening facilitated by the law schools.

To discuss the report’s findings and next steps for engineered carbon removal in California, UC Berkeley and UCLA Schools of Law will host a free webinar on Wednesday, January 27th from 10-11am PT with an expert panel, including:

- Uduak-Joe Ntuk, California State Oil and Gas Supervisor, California Geologic Energy Management Division (CalGEM)

- Anne Canavati, Research Analyst, Energy Futures Initiative

- Keith Pronske, President and Chief Executive Officer, Clean Energy Systems

You can RSVP for the webinar here.

Download the report here.

With the presidential election over, Joe Biden faces a U.S. Senate that still hangs in the balance. But even with a Democratic runoff sweep in Georgia next month, it will be very divided. So what will be possible for a President Biden and his administration to achieve on climate change?

Agency action, foreign policy changes, and spending can all make a difference on emissions, with any COVID stimulus and budget deals with Congress, if feasible, providing potential avenues for further climate action. Here are some ideas along those lines, broken out by key sectors of the economy.

Action on Transportation

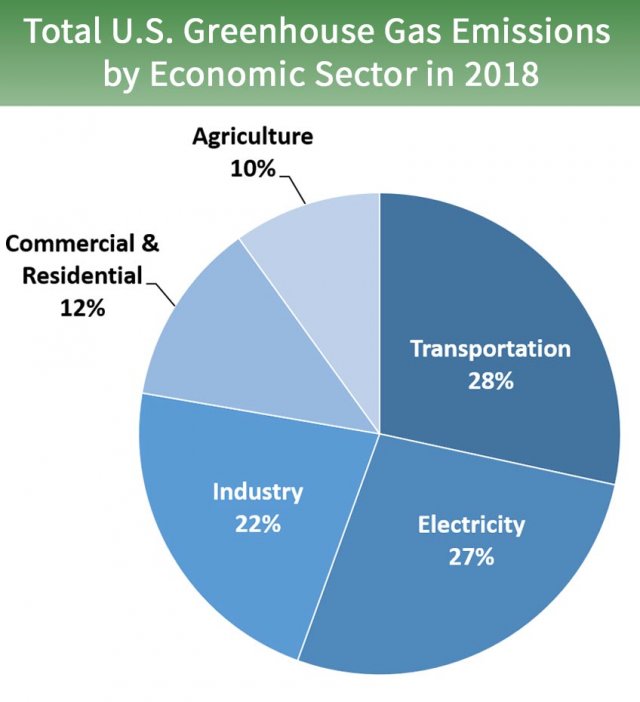

As the EPA chart above of 2018 emissions shows, transportation contributes the largest share of nationwide greenhouse gas emissions at 28%. The best way to reduce those emissions is to decrease per capita driving miles through boosting transit and the construction of housing near it, as well as switch to zero-emission vehicles, primarily battery electrics.

Transit-oriented housing is largely governed by local governments, who generally resist construction. Absent state intervention or federal legislation from a divided Congress, the Biden administration will have to make surgical regulatory changes directing more grant funds to infill housing and potentially use litigation and other enforcement tools to prevent and compensate for racially discriminatory home lending and racially exclusive local zoning and permitting practices.

On transit, a Biden administration would be very pro-rail, especially given the President-elect’s daily commuting on Amtrak in his Senate days. If the Senate flips to the Democrats, high speed rail could be a big part of any bipartisan COVID stimulus package, if it happens, which would be a lifeline to the California project that is otherwise running out of money. Other urban rail transit systems could benefit as well, and the U.S. Department of Transportation could favor and streamline grants for transit over automobile infrastructure. Notably, LA Metro CEO Phil Washington, responsible for implementing the nation’s most ambitious rail transit investment program in Los Angeles County, is chairing Biden’s transition team on transportation.

On zero-emission vehicles, Biden may have relatively strong tools to improve deployment of this critical clean technology. First, perhaps through a budget agreement with Congress, he could reinstate and extend tax credits for zero-emission vehicle purchases, which have expired for major American automakers like General Motors and Tesla. Second, he could use the enormous purchasing power of the federal government to buy zero-emission vehicle fleets. And perhaps most importantly to California, his EPA can rescind its ill-conceived attempt at a fuel economy rollback for passenger vehicles and then grant the state a waiver under the Clean Air Act to institute even more stringent state-based standards, toward Governor Newsom’s new goal of phasing out sales of new internal combustion engines by 2035.

Reducing Electricity Emissions

The electricity sectors comes in a close second place, with 27% of the nation’s greenhouse gas emissions. The move toward renewable energy, particularly solar PV and wind turbines, is so strong that even Trump had difficulty slowing it down during his single term in office, in order to favor his fossil fuel supporters. But nonetheless, the Trump administration created some strong headwinds which can now be reversed.

First and foremost, President-elect Biden can drop the tariffs on foreign solar manufacturers, which drove up prices for installation here in the United States. Second, as with the zero-emission vehicle tax credits, a budget deal with Congress could bolster the federal investment tax credit for solar, which steps down from the initial 30% toward an eventual phaseout for residential properties and 10% for commercial properties. The credit could also be extended to standalone energy storage technologies, like batteries and flywheels, if Biden budget negotiators play their hands well (easy for me to say). A Biden administration could also improve energy efficiency by dropping weak regulations on light bulbs and appliances like dishwashers at the U.S. Department of Energy and introducing more stringent ones instead.

Legislatively, any COVID stimulus deal (again, if it happens) could potentially contain money for a big renewable energy buildout, including for new transmission lines, grid upgrades, and technology deployment. In terms of regulations, if Biden is able to get any appointments through the Senate to agencies like the Federal Regulatory Energy Commission (FERC), that agency could make climate progress by simply letting states deploy more renewables and clean tech, including demand response, as well as potentially supporting state-based carbon prices (a move supported by Trump’s FERC appointee Neil Chatterjee, which promptly resulted in his demotion last week).

Slowing Fossil Fuel Production

The two big moves for the Biden administration will be to stop new leases for oil and gas production on public lands (including immediately restoring the Bear’s Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante national monuments) and bringing back the methane regulations on oil and gas producers that the Trump administration rolled back. As a bonus, his Interior Department could engage in smart planning to deploy more renewable energy on public lands, where appropriate, including offshore wind.

Other Climate Action

The list goes on for how the Biden administration can embed smart climate policy into all agencies and facets of government, with or without Congress. Of particular note, his appointees at financial agencies like the Federal Reserve and U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission could bolster and require climate risk disclosures for institutional and private investors. The U.S. Office of Management and Budget could ramp back up, based on the best science and economics, the social cost of carbon, which represents the cost in today’s dollars of the harm of emitting a ton of carbon dioxide equivalent gas into the atmosphere. This measure provides much of the economic justification for the federal government’s climate regulations. And of course, President-elect Biden can have the U.S. rejoin the 2015 Paris climate agreement immediately upon being sworn in (though the country will need to set a new national target).

Overall, Biden’s win means the U.S. will regain some climate leadership at the highest levels, with much that can be done through congressional negotiations, agency action, and spending. However, the stalemate in the US Senate likely means that any hopes for big new climate legislation will be dashed. As a result, continued aggressive action at the state and local level, as well as among the business community, will be critical to continue to help push the technologies and practices needed into widespread, cost-effective deployment to bring down the country’s greenhouse gas footprint.

One election certainly won’t solve climate change, and the costs continue to rise to address the impacts we’re already seeing from extreme weather. But given the current political climate, the actions described above could allow the U.S. to still make meaningful progress to reduce emissions over the next four years and beyond, even in an era of divided government.

On tonight’s City Visions, we’ll discuss California’s Prop 22, which would keep gig economy workers classified as independent contractors. We’ll ask: is the gig economy good for workers, or are they being exploited by it?

Companies like Uber, Lyft and Postmates have spent over $180 million dollars on the “Yes on 22” campaign, but polling suggests voters are still evenly divided on this question. Tune in to find out more!

We will also hear a COVID update and guest correspondent Sarah Ladipo Manyika’s edited interview of Marin-based poet Jane Hirshfield. Joining me at 6pm will be:

- Erin Allday – Health reporter for the San Francisco Chronicle

- Dr. Peter Chin-Hong – Infectious disease specialist at UCSF

- David Cruz – National Communications Director for the League of United Latin American Citizens and President of Council 3288

- Cherri Murphy – Lyft driver, Social Justice Minister, Gig Workers Rising leader, and Ph.D candidate at the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley

- Jane Hirshfield – award-winning poet, essayist, founder of Poets for Science, and practitioner of Zen for over 40 years. Her ninth book of poems, entitled Ledger, was published in March. You can find Jane’s work here.

Call us during the show at 6pm with your questions at 866-798-TALK or send an email to cityvisions@kalw.org. We’re airing on 91.7 FM KALW in San Francisco and streaming live. Hope you can join us!

Housing policy is at the center of all of our major societal problems in the United States:

- Care about racial justice? Restrictive housing and land use policies are responsible for our deeply segregated towns and cities.

- Climate change? Bad housing policies are the reason why so many people are forced into long, emission-spewing commutes, because they can’t afford to live close to their jobs.

- Economic inequality? Inflated home prices and rents increasingly force middle- and low-income residents into low-opportunity areas, while shutting them out of the wealth-generating possibilities of home ownership. Just to name a few issues affected by housing.

So why can’t we address the high cost of housing, particularly near transit and jobs? There are two culprits: high-income homeowners who support exclusionary local land use policies that restrict housing supply, which prevents others from moving into their communities and deprives them of the educational and economic opportunities that come with living in these areas. Second, the state and federal government is unwilling to provide sufficient public subsidies for affordable housing (though the scale of the need at this point is simply massive, especially given the country’s inability to build housing at a reasonable price).

Perhaps with these dynamics in mind, then-Lieutenant Governor Gavin Newsom campaigned for governor in 2018, promising 3.5 million new housing units to address the state’s severe housing shortfall. But after two legislative sessions, the Governor so far has no meaningful legislative accomplishments on increasing housing production. Like 2019, this just-concluded 2020 legislative session proved to be a bust (yes, Covid-19 interfered, but housing was one of the few remaining priorities that the legislature was committed to addressing this year).

Here are the gory details of the housing bills from the original legislative “housing package” in January that did not survive:

Assembly defeats:

- AB 1279 (Bloom): would have identified high-resource areas with strong indicators of exclusionary patterns and require zoning overrides to encourage production of small-scale market-rate housing projects and larger-scale mixed-income affordable projects.

- AB 2323 (Friedman): would have expanded CEQA infill exemptions to projects in low-vehicle miles traveled (VMT) areas.

- AB 3040 (Chiu): would have incentivized cities to upzone to allow for fourplexes in neighborhoods currently zoned solely for single-family housing.

- AB 3107 (Bloom): would have allowed streamlined rezoning of commercial land for housing.

- AB 3279 (Friedman): would have amended administrative and judicial review for various projects under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA).

Senate defeats:

- SB 899 (Wiener): would have streamlined review for religious institutions seeking to build housing on their property.

- SB 902 (Wiener): would have streamlined approval for up to 10 housing units per parcel near transit.

- SB 995 (Atkins): would have fast-tracked CEQA review for environmentally beneficial infill projects.

- SB 1085 (Skinner): would have expanded density bonus law by allowing rental housing developers to increase the size of their projects 35% if at least 20% of the units were moderately priced (rent at 30% below market rate for the area).

- SB 1120 (Atkins): would have allowed two homes on every property zoned for single-family homes in California; would have also allowed single-family properties to be split into two lots.

- SB 1385 (Caballero): would have made it easier to rezone commercial land for housing and streamline approval for projects on that land.

- SB 1410 (Caballero): would have provided rental relief through tax credits to landlords to fill unpaid rent.

It’s also worth reiterating that the senate voted down in January an amended version of Senate Bill 50 (Wiener), which would have reduced local restrictions on apartments near major transit and jobs.

And strangely, SB 995, SB 1085, and SB 1120 all passed the Assembly at the last minute, but Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon scheduled the vote too late for a concurrence vote in the Senate. As a result, the bills died.

But the news was not all bad. Some housing bills did pass, including:

- AB 725 (Wicks): requires that no more than 75 percent of a city’s regionally assigned above-moderate income housing quota can be accommodated by zoning exclusively for single-family homes, with the remainder on sites with at least 4 units.

- AB 1851 (Wicks): requires local governments to approve a faith-based organization’s request to build affordable housing on their lots and allows faith-based organizations to reduce or eliminate parking requirements.

- AB 2345 (Gonzalez): increases the density bonus and the number of incentives available for a qualifying housing project.

- SB 288 (Wiener): temporarily exempts from CEQA review infill projects like bike lanes, transit, bus-only lanes, EV charging, and local actions to reduce parking minimums, among others, until 2023 (disclosure: I helped Assemblymember Laura Friedman and Assembly Natural Resources Committee chief consultant Lawrence Lingbloom draft the parking provision, along with Mott Smith of the Council of Infill Builders).

So there we have it in 2020. A few successes, but mostly a wipeout. Perhaps recognizing the urgency after two failed sessions, Governor Newsom appeared this week to offer something of a belated endorsement of SB 50 and SB 1120, two of the more consequential bills that failed in the legislature this year:

But absent strong leadership from the Governor’s office and legislative leaders, this pattern of failure on housing production will likely continue, exacerbating all the challenges I discussed above that are affected by dysfunctional housing policy. That means we can expect worsening racial injustice and segregation, greenhouse gas emissions, and economic inequality, to name just a few, until the state can finally, meaningfully address this problem.

Marlene Sekaquaptewa was a tribal leader, village governor, and devoted family matriarch at the Hopi Reservation in Arizona. She was also a work colleague of mine — but much more than that. She was a beloved mentor, auntie to my family, and inspiration for public service. She died in June after testing positive for COVID-19 at the age of 79, just a few weeks shy of her 80th birthday.

I first met Marlene through her niece, my UCLA Law tribal legal development clinic instructor Pat Sekaquaptewa (pronounced roughly see-KIA-cwop-tee-wah). Along with Pat and her Berkeley Law classmate and colleague Justin Richland, the four of us founded The Nakwatsvewat Institute in 2005, to improve tribal governance and education to better reflect cultural values and community needs. Our first project involved developing a mediation service for the semi-sovereign villages of the Hopi Tribe, and Marlene served as the organization’s cultural consultant.

Little did I know that I was in the presence of the matriarch of a family dynasty at Hopi. Marlene’s mother Helen was a homemaker who wrote a 1969 book on her life story called “Me and Mine.” Her father Emory was a farmer and tribal judge. Her brother Abbott served as a longtime Hopi Tribal Chairman. Her other brother Emory, Jr. wrote the first Hopi dictionary. And her daughter Pat continues the tradition by serving as Hopi Appellate Court Justice. Marlene herself ended up serving on the Hopi Tribal Council and as governor of her village, Bacavi.

Marlene was completely dedicated to two things: her community and her family. She had a knack for recruiting people to help her community, whether it was hosting wayward graduate students like Justin in her basement or making sure guests like researcher Peter Whiteley were honored at ceremonial dances (even if, as Peter recalled at Marlene’s recent memorial service, he had no idea why the dancers were calling him down to the plaza in front of the whole village). She similarly welcomed me and my family into her home, treating us like extended family.

And she loved to talk politics. We had to devote the first 20 minutes of any work meeting to discuss the latest shenanigans by Hopi politicians. But she didn’t just complain. She ultimately helped draft a new Hopi Tribal Constitution in 2012 and had recently helped create an assisted living facility for Hopi elders.

Family was also her passion. She once told me, “Without family, we are nothing.” And she had a big one. Along with her late husband Leroy Kewanimptewa Sr., Marlene had five children. Two predeceased her, Kenneth and Paul, but she is survived by her daughter Dianna Shebala; two sons, Leroy Kewanimptewa Jr. and Emory Kewanimptewa; 14 grandchildren; and 12 great-grandchildren.

To read more about Marlene’s remarkable life and contributions, you can read the recent New York Times obituary. Marlene also narrated in 2018 this PBS special on the Hopi origin story, so you can hear her voice in her native language:

And finally, to get a sense (for those who have never been to Hopi) what the village and ceremonial life is like there, below is a video of the Eagle Dance at Marlene’s neighboring village of Hotevilla, which is appropriate since she was Eagle Clan (determined at Hopi by the clan of your mother).

To say I will miss Marlene is an understatement. She loved Hopi, was immensely proud and knowledgeable about her culture, and opened her heart to everyone she met. She was a strong matriarch who was not afraid to speak her mind. Many in her community and family depended on and loved her. But we will continue her work at Hopi and other tribal communities in her memory, with the lessons she taught us over the years as both a guide and a lifelong gift.

Rest in peace, Marlene, and thank you.

Jim Mahoney was perhaps an unlikely climate hero. A senior Bank of America and FleetBoston Financial executive for 25 years who tragically passed away this past weekend at the age of 67 (the result of complications from injuries he sustained in a bicycle accident last year), Jim’s work focused on global corporate strategy and public policy for a major financial institution. Climate change would have been just one component of his portfolio of issues affecting banking.

But back in 2008, Jim teamed up with his former boss, then-California Attorney General Jerry Brown, to make a difference on climate policy. Brown and Mahoney, through Brown’s then-climate advisors Ken Alex (now with Berkeley Law) and Cliff Rechtschaffen (now a California public utilities commissioner), approached Rick Frank (now with UC Davis Law) and Steve Weissman (now with the Goldman School) at UC Berkeley Law and Sean Hecht and Cara Horowitz at UCLA Law to launch a Climate Change and Business Initiative at the law schools.

The initiative was only planned for one year, to focus on then-emerging topics in climate policy like infill housing, small-scale renewable energy, low-carbon agricultural practices, and residential energy efficiency financing. The idea was to convene small groups of experts for roundtable discussions that would inform policy reports on business solutions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. These reports in turn would ideally educate California legislators and regulators on cutting-edge, consensus climate solutions.

But with Jim’s quiet but committed leadership at Bank of America, that one-year initiative soon grew to a multi-year program that has to this day covered multiple climate and clean energy issues and influenced legislation and regulation in California and throughout the country. Here are just a few highlights:

- Pioneering climate and clean energy legislation: The initiative helped inform the California’s first-in-the-nation energy storage mandate, which proved so successful that the initial targets have been increased and expanded. It also inspired legislation to streamline permitting for utility-scale solar PV on degraded agricultural land, as well as to increase California’s renewable energy requirements.

- Regulation and funding: Recent work on boosting energy retrofits for low-income multifamily buildings was incorporated into state energy planning, while a biofuels convening helped steer millions of dollars of state energy funding for this low-carbon industry.

- Inspiring out-of-state action: A number of the in-state policy recommendations have informed similar work elsewhere, such as our stakeholder process to identify prime areas for renewable energy development. And in general, California legislation on climate and energy has inspired similar action across the United States, particularly on renewable energy and zero-emission vehicles.

- Cataloguing climate solutions: All of the initiative’s recommendations over the years are compiled in the easy-to-use website climatepolicysolutions.org.

- Influencing public debate: In addition to convenings and reports, the initiative has led to publication of numerous op-eds (most recently on ways to make the electricity grid more resilient and low-carbon), webinars (such as on priority climate solutions with California’s top climate leaders), and conferences (including recently on expanding zero-emission freight technologies at Southern California’s ports).

- Training future climate leaders: Throughout the research involved with this initiative, the law schools have included numerous law students and recent graduates to help conduct that work. Many of them have gone on to further this work through their professional employment at law firms, clean technology companies and government agencies, among others, with one recent fellow now advising the Biden campaign on climate policies.

And on a personal note, Jim’s initiative provided me with an opportunity to dedicate my career to working on all of these important issues, as I was first hired at Berkeley Law for that one-year initiative before eventually directing the climate program at the law school’s Center for Law, Energy and the Environment (CLEE).

While many individuals have been involved in the Climate Change and Business Initiative over the years, none of this work would have been possible without Jim’s leadership at Bank of America. Along with his colleagues, including Rich Brown, Brian Putler, Kaj Jensen, Alexandra Liftman, and others, Jim ensured that the initiative had strong institutional support and funding to carry out this work, without ever interfering or trying to influence the content of what the initiative covered or recommended. Quite the opposite, he helped the law schools’ harness the Bank’s expertise and contacts to further the dialogues and reach of the findings.

Jim’s death is a blow to his family, friends, colleagues, and those of us who care about the issues he helped advance. The Boston Globe published a worthy tribute to his career and extensive family, including his volunteer stint driving then-presidential candidate Jerry Brown around New Hampshire and Wisconsin.

Jim will be missed, but his legacy of climate leadership will live on in the work and policies he helped advance, and in the lives he touched. May he rest in peace.

On January 27, 2017, just one week after Trump’s inauguration, UC Berkeley Law’s Henderson Center for Social Justice held a daylong “Counter Inauguration,” featuring various panels in reaction to Trump’s victory. I spoke on an afternoon panel that day entitled “Monitoring the Environmental, Social and Governance Impacts of Business in the Trump Era” and offered my predictions on what the Trump years would bring for environmental law and policy.

I recently reviewed these predictions, three months out from the upcoming November election, to see how they measured up against the reality of Trump’s near-complete term in office. Bottom line: these predictions mostly tracked with what happened with Trump and his administration’s leaders, albeit with some steps I missed, some that never came to pass, and some positive outcomes for environmental protection.

First, I predicted the Trump Administration would follow through on the campaign pledges to boost fossil fuels in the following ways:

- Opening up public lands for more oil and gas extraction

- Slashing regulations that limit extraction and related pollution, such as the Clean Power Plan and methane rules

- Weakening fuel economy rules for passenger vehicles

- Financing more infrastructure that could boost automobile reliance (i.e. more highways and less transit)

These were all relatively predictable actions, and they all pretty much happened as predicted. On public lands and fossil fuels, Trump rolled back National Monument protection at Utah’s Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante, as well as streamlined permitting for oil and gas projects on public lands. On environmental rules in general, here is a list of 100 environmental regulations that the administration has tried to reverse. On vehicle fuel economy standards, here’s my article on EPA’s proposed rollback. And transit funding went from 70 percent of transportation grants under Obama to 30 percent under Trump, with the rest funding highways.

Second, I predicted that his administration would try to undermine clean technologies by:

- Weakening tax credits for renewables and electric vehicles

- Undoing federal renewable fuels program

- Revoking California’s ability to regulate tailpipe emissions

- Attempting to undermine California’s sovereignty to regulate greenhouse gases through legislation

- Cutting funding for high speed rail and urban transit

- Withdrawing from Paris agreement

On these predictions, I was correct on most accounts. The administration did weaken tax credits for renewables (both by not extending them or preventing them from decreasing over time, save for a recent one-year extension on wind energy as a budget compromise) and electric vehicles (by letting them expire and threatening to veto Democratic legislation that would have extended them in a recent budget bill). His EPA did revoke California’s waiver to issue tailpipe emission standards. And he famously withdrew from the Paris agreement (to take actual effect later this year) and has tried to cancel almost $1 billion in high speed rail funding in California.

But I was incorrect that the administration would pursue legislation to preempt California’s (and other states’) sovereignty to set their own climate change targets. There was little appetite in Congress to do so, though Trump’s Justice Department did seek unsuccessfully to declare California’s cap-and-trade deal with Quebec to be unconstitutional. And his record on renewable fuels is more mixed but did deliver some gains to corn-based ethanol producers, though the environmental benefits are suspect with this type of biofuel. I also failed to predict the administration’s efforts to impose tariffs on foreign solar PV panels and wind turbines, which slowed those industries somewhat.

Finally, I predicted some possible bright spots for the environment in the Trump years, much of which did occur:

- Clean tech generally has bipartisan support in congress

- Infrastructure spending in general could be negotiated to benefit non-automobile investments

- Lawyers can stop or delay a lot of administrative action on regulations

- A shift will happen now to state and subnational action on climate, which probably needed to happen anyway

Sure enough, clean technology, particularly solar PV, wind and batteries, has continued to increase in the Trump years, though not at the same pace as under Obama due to the policy headwinds. But infrastructure spending has definitely favored automobile interests, as noted above.

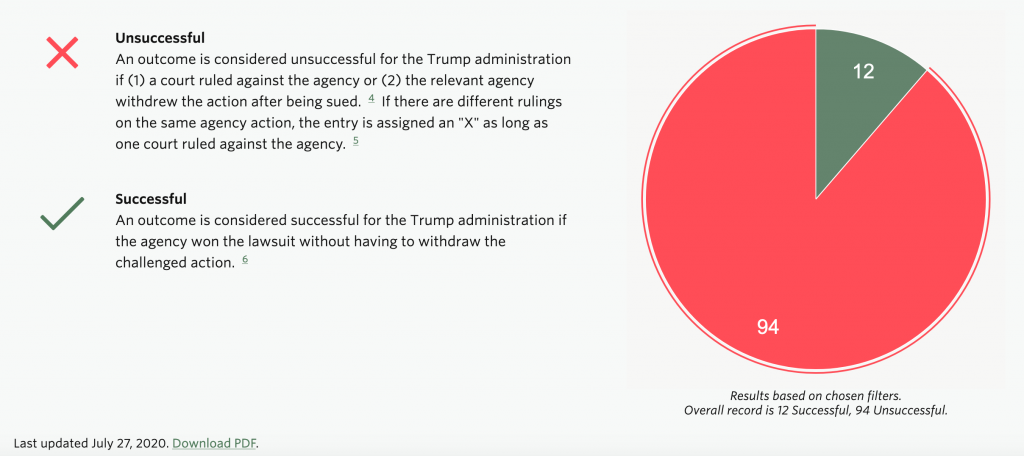

But more importantly, two critical predictions did come to pass. First, attorneys have successfully stopped most administrative rollbacks. In fact, the administration has an abysmal record defending its regulatory actions in court. As NYU Law’s Institute of Policy Integrity has documented, the administration has lost 94 cases in court and won only 12 to date, as tracked in this chart:

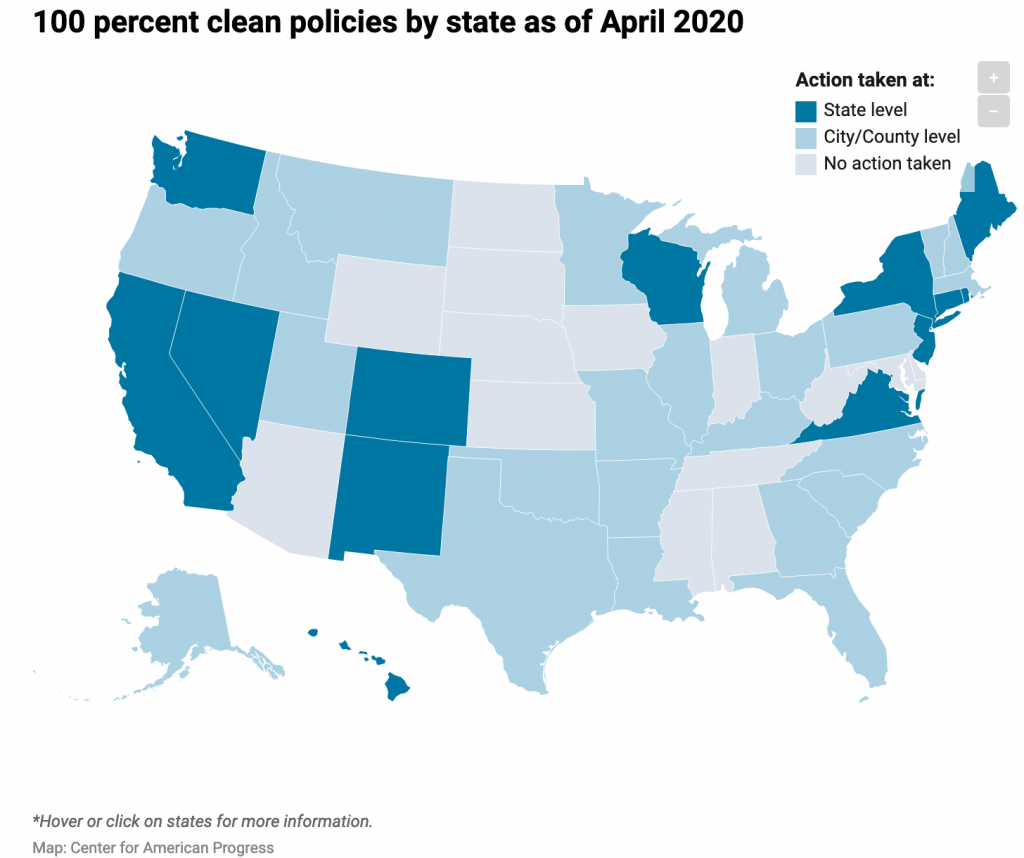

And perhaps more importantly, the lack of federal climate action has moved the spotlight to state and local governments, which often have significant sovereignty to enact aggressive policies that add up to serious national climate action. Take renewable energy, for example, per the Center for American Progress, with this map of states and municipal governments that have enacted 100% clean electricity standards:

And on clean vehicle standards, 13 states plus the District of Columbia now follow California’s aggressive zero-emission vehicle standards, representing about 30 percent of the nation’s auto market.

As a result, in many ways, environmental law and climate action appears to have survived the Trump term in office mostly intact, despite losing progress and facing some setbacks on key issues. Most of the regulatory actions can be reversed by a new administration, while Congressional action during the Trump years was relatively minimal in scope. Meanwhile, the counter-reaction to Trump spurred some significant policy wins at the state and local level.

But while one term is perhaps survivable for environmental law and climate progress, a second one could paint a completely different picture. So the stakes certainly remain high this November.

Imagine: a severe pandemic races through the United States, hitting cities like New York hard. Public transit is partially blamed for the spread, given that transit works best by squeezing in a lot of people in tight places to move them efficiently.

What happens next, as the virus dissipates? After a few years dealing with panic and fear of being too close to others, how will urban residents react?

In response, residents could start to abandon cities and the public transit they depend on. Americans might choose to move out of high-cost, dense transit-dependent urban areas to emerging lower-cost, western cities, built around the automobile and single-family homes. They might abandon transit forever.

The result could be catastrophic, an environmental wasteland dominated by suburban sprawl, crushing traffic, and choking pollution, with little open space or agricultural land preserved. Those left behind in cities to ride transit will predominantly be lower-income individuals who can’t afford a car or single family home – too often people of color. This dynamic will only worsen racial disparities, and transit service, already underfunded, will worsen.

But this harsh reality is actually not the future — it’s what already happened in our past. Specifically, after the 1918-1920 Spanish Flu, urban residents abandoned American cities, particularly in the East Coast, lured to the cheap housing and car culture of places like Los Angeles. Developers sold the West Coast “car suburb” to newcomers as offering an escape from disease-ridden cities. The result was the environmental degradation and ongoing racial residential segregation we see today.

To be sure, since Spanish Flu times, trends on transit have reversed to some extent. Urban rail transit launched a comeback starting in the 1960s, and cities have since been revitalized with strong demand for housing. Voters have increasingly taxed themselves to build more and better transit, particularly with local sales tax measures.

And in the Spanish Flu era, the automobile was new and exciting, but the limits of the technology were not yet widely understood. Consumers only saw the upsides of driving, not the downsides of increased traffic, pollution, transportation costs, suburban isolation and lost open space. Since that time, we’ve learned many of those lessons and implemented new environmental policies to counteract the pollution and sprawl.

But public transit is indeed in serious danger. Fear is powerful, and those with means will choose to drive or work from home instead of taking on the risk of getting the virus from transit. Those with no other option, such as people with low-incomes, service jobs requiring in-person work, or disabilities, will have no other choice, exacerbating social inequities.

The result will be a downward spiral: as ridership plummets, budgets take a hit, transit service is cut back, and the systems overall can become unappealing to lure “choice” riders back who could otherwise drive.

This future in many ways is already here, in the initial months of COVID sheltering. As Janette Sadik-Khan and Seth Solomonow noted recently in The Atlantic, ridership on bus and rail systems has already dropped from pre-pandemic levels by:

- 74 percent in New York

- 79 percent in Washington, D.C.

- 83 percent in Boston

- 87 percent in the Bay Area

We all have a stake in making sure this outcome isn’t permanent. Transit is essential for cities, as our economic and cultural engines, to function well. We also need transit to reduce driving miles and pollution and reduce pressure to sprawl. And transit can address equity concerns, by providing mobility for those who can’t afford a vehicle.

So how do we save public transit post-Coronavirus and not repeat the mistakes of the past?

First, transit officials and advocates need to address the public’s fear. The evidence on viral spread via transit is mixed at best. On its face, we’ve seen outbreaks in places with heavy public transit use, like in New York City, so the public and some scientists have superficially connected transit ridership with disease spread.

But recent studies in Paris and Austria showed no spread from transit. And looking at the geography, it’s hard to see a connection between COVID and transit:

- Hong Kong with heavy transit use has recorded one-tenth the number of cases as Kansas

- In New York, car-heavy Staten Island has had higher infection rates than transit-dependent Manhattan

- Cities in South Korea, Taiwan and Japan have had little infection compared to suburban parts of the US or Italy, where outskirts of Milan were hit harder than the city itself

In general, spread seems to be more acute in places like nursing homes and prisons and among families living together, not via transit.

Second, transit officials should point to and replicate success stories. Taipei in Taiwan provides perhaps the gold standard. Taiwan officials require mandatory mask wearing on trasit. They use noninvasive handheld or infrared thermometers to screen all riders. They test, trace and quarantine, and they clean the systems well. Transit officials also adjust service to limit crowding. All of these steps require resources in times of budget crunches, so we’ll need financial support for transit, for both environmental and equity reasons.

Third, officials can highlight the miserable alternative to supporting transit. Without transit, we would see significantly more traffic congestion, including traffic deaths (averaging about 37,000 in the US per year). We’d also see more pollution, imperiling our air quality, public health, equity, and climate goals.

Fourth, we need to boost non-automobile alternatives to transit. These options include “active” transportation, timely with e-bike sales skyrocketing and the proliferation of e-scooters. Cities can also explore employing more shuttles and vans instead of mass transit. And they can set aside street infrastructure for all of these uses, as well as offering rebates and other incentives to encourage e-bike and e-scooter purchases, to replicate success we’ve seen with zero-emission passenger vehicles.

And there looms one major, yet controversial idea to consider for the long term: replacing all rail transit with far-cheaper and more efficient automated, electric bus-rapid transit lines (ART) on the dedicated lanes of former rail tracks. This transition would harness new technology in self-driving software and improvements in batteries to save transit agencies orders of magnitude in costs for operations and maintenance compared to rail. And with rows of connected buses, ART can replicate the capacity and electric propulsion of rail at a fraction of the time to build and money to operate — timely for squeezed transit agency budgets. Now might be the time for transit agencies to study these conversions.

In the future, public transit post-COVID doesn’t necessarily have to replicate the past. But unless we act now to bolster public transit and its sustainable alternatives, we may indeed find ourselves moving backwards, in more ways than one.

California law under SB 100 (De León, 2018) requires that our electricity system run on 100% carbon-free power by 2045. That means a significant deployment of energy storage resources, like batteries, to capture surplus renewable power from the sun and wind for dispatch during dark and windless times.

While passing this law was a milestone, actually achieving this target will require siting and permitting major clean energy facilities. And perhaps no better land is appropriate for these facilities than at existing fossil fuel plants. These plants are on already-industrialized land with access to transmission lines. Converting them to energy storage facilities is a double-win: it offers a phase out of fossil fuels, while improving the air quality (and often the aesthetics) of the surrounding area.

So that’s why it’s frustrating to see one such proposed conversion to battery storage — the Moss Landing power plant battery energy storage project — potentially held up for months now by local opposition. The Monterey County Planning Commission will consider the project at its July 29th hearing.

The proposed project involves a 1,200-megawatt (MW) battery energy storage system, fit into the existing industrial footprint of the Moss Landing power plant in four two-story buildings, along with associated infrastructure (substations and inverters/converters). It will also replace existing lattice transmission towers with monopoles (staff report available here).

Most importantly, the goal of the project is to store renewable energy from the sun and wind to help California decarbonize its electricity grid. For this reason, Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E, the local utility) selected the project and brought it to the California Public Utilities Commission for approval, with a condition that the project reach commercial operation by July 18, 2021 (PG&E advice letter here).

But a good proposal to support needed climate policy is not always enough in California. Permitting any industrial project comes with challenges and opposition, most notably compliance with environmental review under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA).

In this case, a review of the project under CEQA by the county revealed no significant impacts on the myriad study areas, including air quality, biological resources, water, traffic, cultural resources, and others; provided the developer implement appropriate mitigation measures. However, the developer ended up going beyond the county’s recommendations by committing to a dialogue process to identify additional mitigation measures to protect migratory birds. In short, the developer agreed to go above and beyond what CEQA requires.

Furthermore, in collaborating with the National Audubon Society and Monterey Audubon, the developer agreed not to include new transmission poles and high-voltage wires until after 2020, at which point they will conduct final design in consultation with those nonprofits. The company further committed to addressing bird safety issues in that process, including consideration of undergrounding high-voltage transmission wires.

Ultimately, the clean energy nature of the project, the county’s preparation of an environmental review document that follows CEQA, and this additional commitment to address bird safety issues were enough to gain the support of Audubon and the Sierra Club. The project appeared to face relatively easy sailing to a permit, but the planning commission delayed considering it at its July 8th meeting so that the environmental review document could be revised to clarify transmission wire placement associated with the project. Hopefully, the commission approves the project on July 29th, and no one appeals it to the Monterey County Board of Supervisors.

If California can’t allow relatively straightforward permitting of energy storage facilities at existing power plants with minimal anticipated impacts, where can they go? Not only will clean tech companies shy away from investing in California, potentially driving up costs from lack of competition, but these eyesore power plants may take longer to decommission. In the case of Moss Landing, the power plant has 500-foot dual smokestacks visible through Monterey Bay, a source of visual blight and air pollution in an otherwise unique marine and coastal environment. This battery storage project could help facilitate this decommissioning sooner rather than later, while embodying precisely the critical energy storage deployment California needs to achieve a decarbonized future.