It may seem obvious (apparently unless you’re a millennial), but people who take out their smart phones during a meeting are irritating their bosses and colleagues, according to a recent survey. (Full disclosure: I’ve been guilty of this habit.)

Researchers from USC’s Marshall School of Business asked this question of 554 full-time “working professionals” (defined as earning above $30,000 and and working in companies with at least 50 employees) around the country. They found overwhelming dislike of the smart phone habit during meetings, as Dr. Travis Bradberry summarized on a recent LinkedIn post:

- 86% think it’s inappropriate to answer phone calls during meetings

- 84% think it’s inappropriate to write texts or emails during meetings

- 66% think it’s inappropriate to write texts or emails even during lunches offsite

- The more money people make the less they approve of smartphone use.

- For most people, smart phone use by a colleague shows a lack of respect, attentiveness, and self-awareness among the users.

But the survey revealed an interesting gender and generational breakdown: while women and people over forty are the most bothered, millennials are three times more likely than those over 40 to think that smartphone use during meetings is okay.

You could probably extrapolate these findings to any setting, not just in the workplace. After all, it’s hard to feel special when the person or people you’re with would prefer to check their phones than relate to you.

But at the same time, the culture is clearly changing. For younger people who have grown up with these devices, they apparently don’t take as much umbrage at their usage by the people with them.

Maybe that’s a good thing. Or maybe it’s just a necessary cultural adaptation, as these addictive devices continue their relentless conquest of our attention spans and daily habits.

Some environmentalists have noted with schadenfreude that the auto industry is getting its just desserts now for pressing the Trump administration to weaken Obama-era fuel economy standards. While the auto industry may have originally just wanted some additional flexibility for compliance, instead they got a wholesale revocation of the program.

And this rollback means a worst-case scenario for the auto industry, with potentially years of litigation and uncertainty to come. In short, they won’t know what type of vehicles to produce for the next few years at least.

So if the auto industry didn’t want the administration to take this approach, why is it happening? The answer may involve the other industry that benefits from weakening fuel economy standards: Big Oil. As Bloomberg reported:

The Trump administration’s plan to relax fuel-economy and vehicle pollution standards could be a boon to U.S. oil producers who’ve quietly lobbied for the measure.

The proposal, released Thursday, would translate into an additional 500,000 barrels of U.S. oil demand per day by the early 2030s, about 2 to 3 percent of projected consumption, according to government calculations.

Apparently oil industry leaders have been quietly lobbying for this action, including Marathon Petroleum Co., Koch Companies Public Sector LLC, and the refiner Andeavor. In fact, on the KQED Forum show I participated on this past Friday, one of the guests supporting the rollback was from the Koch-funded think tank “Pacific Research Institute.”

So it looks like Big Oil doesn’t really care if the auto industry twists in the wind on the rollback, if it means the possibility of selling a lot more climate-destroying oil in the meantime.

I’ll be on KQED radio’s Forum this morning at 9am discussing the Trump Administration’s proposed rollback of federal vehicle fuel economy standard and revocation of California’s zero-emission vehicle mandate. We’ll discuss the proposal, potential policy responses, and the future of judicial challenges to it.

Tune in at 88.5 FM in the San Francisco Bay Area and weigh in with your questions. Even if you don’t live in the Bay Area, you can stream it live and call in or email with questions.

San Francisco is about to open its new $2.2 billion Transbay Terminal in downtown, current home to transbay bus service and future home to Caltrain and high speed rail. I had an opportunity to tour the facility last week ahead of its big public opening on August 12th (photos below).

The new terminal replaces a 1930s era bus depot that used to receive San Francisco’s since-shuttered intercity electric trains coming off the lower deck of the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge. But the eight-year construction project has been mired in controversy over the typical delays and budget-busting that you see with big new infrastructure projects. And it also has been blamed for contributing to the nearby Millennium tower sinking and shifting, based on the dewatering practices used to excavate the site.

My takeaway from the tour? It’s a beautiful building that will really help smooth bus transportation access to this growing neighborhood south of Market Street. And the other immediate benefit will be the rooftop park, which is reminiscent of Manhattan’s highly successful “high line” walkway.

But the long-term payoff will be if and when Caltrain and High Speed Rail begin service to its now empty basement level — though that may take more than a decade to come to fruition.

Below are some photos I took from above, within, and below the site.

First up, the view of the 5.4 acre rooftop garden from the Transbay Terminal project office:

Here’s a small-scale model displayed in the project office:

Here’s a small-scale model displayed in the project office:

Once inside the “Grand Hallway” of the terminal on the ground floor, the design team planned a mosaic floor covered in bright California poppies:

Once inside the “Grand Hallway” of the terminal on the ground floor, the design team planned a mosaic floor covered in bright California poppies:

In the basement, possibly the most hopeful yet depressing sight: where Caltrain and possibly high speed rail trains will arrive and depart (probably in the 2030s), serving downtown San Francisco with thousands of passengers each day (pending the funding to complete these multi-billion dollar projects):

On the second floor, you’ll find the new bus bridge from the terminal on that level, taking buses directly onto the Bay Bridge for service to the East Bay and beyond:

On the second floor, you’ll find the new bus bridge from the terminal on that level, taking buses directly onto the Bay Bridge for service to the East Bay and beyond:

And on the top floor, the aforementioned 5.4 acre rooftop park. Although it’s not as convenient to access as a street-level park, the concert series in this future bandstand and other activities should attract people, plus the nice views:

The half-mile bike- and scooter-free walkway around the top feels like a West Coast high line:

The park also features a fun access feature: a new gondola that will ferry people to the top from the street, hopefully in an efficient manner. The gondola won’t open until late August or early September:

Families with children will be welcome at this playground on the rooftop:

Overall, the terminal will be a real jewel for this part of San Francisco and a nice way to take transit. But it’s full potential won’t be realized until federal, state and local officials find the money first to extend Caltrain into it and then one day to bring in high speed rail to downtown San Francisco.

Battery electric buses are already cost-competitive with fossil-fueled buses, based on their lower fuel and maintenance costs. Transit agencies around the country are starting to purchase them in bulk from companies like BYD and ProTerra.

But is electricity really cleaner than a natural gas-fueled bus? Union of Concerned Scientists tackled this question in California previously and found positive results, per UCS’s Jimmy O’Dea, and now they’ve taken their research nationwide:

We answered this for buses charged on California’s grid and found that battery electric buses had 70 percent lower global warming emissions than a diesel or natural gas bus (it’s gotten even better since that analysis). So what about the rest of the country?

You many have seen my colleagues’ work answering this question for cars. We performed a similar life cycle analysis for buses and found that battery electric buses have lower global warming emissions than diesel and natural gas buses everywhere in the country.

Here’s the UCS map:

Meanwhile, the buses are getting cheaper and better, as ProTerra’s CEO Ryan Popple explained recently to E&E News [paywalled]:

Meanwhile, the buses are getting cheaper and better, as ProTerra’s CEO Ryan Popple explained recently to E&E News [paywalled]:

When we started out, we could really only do circulator-style routes, and we needed a fast charger for every route. That was probably five years ago, and that was because our maximum theoretical range was probably 50 miles. Now we’re regularly seeing our electric buses do anywhere between 175 and 225 miles in real service. And with all sorts of topography.

But despite the technological advancements and environmental benefits, supportive policy is still needed. Here’s the top of Popple’s policy wish list:

It is at the state of California, and it is the Innovative Clean Transit rule, the ICT. That is headed to the California Air Resources Board for an initial vote, I think, in September, and it could be fully implemented by the end of this year. What that ruling will do is set a long-term target for every transit vehicle in the state of California and a date certain by which it must eliminate its tailpipe emissions, so basically it has to become a zero-emissions vehicle… The reason it matters to us is just so that the industry can move forward with long-term planning on electric fleets.

And as more transit agencies move forward with zero-emission vehicles, we now have assurance that the clean air benefits are real — all across the country.

Join me on-line this Thursday at 11am PT when I serve as the first speaker for California Green Academy and Island Press‘s new Transformational Speaker Series. The series will focus on sustainable transportation and feature leading thinkers in sustainability, urban mobility, and innovative transportation.

As the first speaker this Thursday, I’ll discuss transformational change in Los Angeles transit, which once featured the world’s largest streetcar system. The region then became the nation’s automobile capital but now is undergoing expansive light and heavy rail growth and has an emerging emphasis on multimodal mobility.

Most of my talk will be drawn from my book Railtown (UC Press, 2014). I’ll cover Los Angeles’ current transit transformation – spawned by multiple ballot measures – and the region’s overall mobility future, especially thanks to the passage of 2016’s landmark Measure M.

The inaugural webinar takes place this Thursday, July 26thy, from 11:00-12:00 PST (14:00-15:00 EST). You can stream it live (registration not required) and follow the series on Twitter and YouTube. Hope you can join in!

The U.S. has long lacked a national strategy for reducing carbon emissions. To fill the void, various agencies have proposed a variety of regulations under existing laws, such as efforts to reduce methane emissions in oil-and-gas operations, limit carbon carbon emissions from the power sector (the Clean Power Plan), and promote environmental review of the greenhouse gas impacts of various federally approved projects.

With the death of a proposed federal cap-and-trade program in 2010 under a Democratic congress, some climate advocates now see hope in developing a national carbon tax. This approach makes a lot of sense: it could tax upstream emissions for carbon-based fuels like coal, oil and gas, thereby discouraging their use both by industry and by consumers, who may then seek to reduce consumption of things like coal-based electricity and gasoline for transportation. The revenue in turn could be used to fund various climate-friendly projects or be returned to taxpayers as a dividend.

Supporters actually include some Republicans, who prefer this more minimalist government approach to combating climate change instead of heavy-handed regulations or mandates, such as we see in states like California. To that end, a Florida Republican, Rep. Carlos Curbelo, is about to introduce a carbon tax proposal that is unlikely to go anywhere in this Congress but could serve as an opening salvo and building block for future policy.

E&E News received a copy of the legislation and had this to say about it:

A copy of the draft bill obtained by E&E News calls for eliminating the federal gas tax and replacing it with a $23-per-ton tax on carbon emissions from oil refineries, gas processing plants and coal mine mouths beginning in 2020. Industrial sectors such as cement, aluminum, steel and glass would also pay the fee for emissions stemming from physical or chemical reactions outside of energy production. Sources said Curbelo’s office was shopping that version of the bill last week.

…

It would halt — but not kill — EPA regulations on greenhouse gas emissions so long as the tax meets its goals to cut carbon emissions. The draft legislation contains check-in points in 2025 and 2029 to consider reinstating regulations if the tax hasn’t curbed enough greenhouse gases. The moratorium would sunset after 2033 if emissions goals are met. That provision is meant to address concerns from Democrats and environmental groups, which generally oppose forfeiting EPA’s authority to regulate carbon in exchange for a carbon tax.

Significantly, seventy percent of the revenues would go to the federal Highway Trust Fund to help shore up the dwindling gas tax revenue. The remaining revenue would go to state grants for low-income families to offset higher energy costs, research and development programs, and financing coastal restoration projects.

Meanwhile, companion research from libertarian-oriented think tanks modeled the greenhouse gas benefits. They suggest that emissions would drop 1.2 percent at a tax of $14 per ton, 3.2 percent at $50 per ton and 3.5 percent at $73 per ton. Cubelo’s research shows the policy would reduce greenhouse gas emissions 24 percent below 2005 levels by 2020 and 30 percent below 2005 levels in 2032, exceeding the targets for the U.S. under the Paris accord.

The modelers also claim the carbon tax would have negligible macroeconomic effects, with little change to U.S. GDP. The oil and gas sector would not be affected much, although transportation-sector emissions would generally drop 2 percent. The power sector would see much larger reductions, due to decreased reliance on coal-fired power plants.

The question for Democrats and other climate advocates is whether they would accept a national carbon tax that would displace the various climate regulations — and possibly preempt state action on climate. As my colleague Dan Farber noted on Legal Planet, jurisdictional and regulatory fragmentation on climate policy is advantageous to building political resilience. We’ve seen this play out in practice: the election of someone like Trump poses less of a threat when climate policies are embedded in multiple agencies, statutes, and state and local jurisdictions. A national carbon tax, while perhaps more effective in reducing emissions, flies in the face of that logic because it could swiftly be reversed by a future congress and president.

While decisions won’t have to be made soon on this bill, given the current political climate, climate advocates may soon have to grapple with the carbon tax option — and it’s potential political downside.

How fast will California’s high speed rail system actually go, once it’s fully built between San Francisco and Downtown Los Angeles? Robert Poole at the libertarian Reason Foundation (and an outspoken opponent of the project) runs the numbers:

How fast will California’s high speed rail system actually go, once it’s fully built between San Francisco and Downtown Los Angeles? Robert Poole at the libertarian Reason Foundation (and an outspoken opponent of the project) runs the numbers:

Each time the business plan gets revised, more of the total 434 miles will operate at speeds well below the 220 mph touted by proponents. Los Angeles Times reporter Ralph Vartabedian in March identified another 30 miles that will run at lower speed: the route between San Jose and San Francisco. Instead of running on an elevated track, the HSR will operate on ground-level tracks through a highly urbanized area with numerous grade crossings. CHSRA claims it can safely operate this stretch at 110 mph—but that is not the case for the privately-funded Brightline train in South Florida. Between Miami and West Palm Beach, its allowed top speed is 70 mph—and that is with extensive safety improvements to grade crossings. Reviewing various CHSRA documents assessed by Vartabedian, I found 91 miles that will likely be restricted to 70 mph and another 45 miles in tunnels where speeds will likely be no higher than 150 mph. Assuming that on the remaining 298 miles the average speed will be 200 mph (due to grades, slowing down for the slower sections, etc.), my estimate of the total elapsed time between Los Angeles and San Francisco is 3.09 hours. And that is a problem, since the ballot measure approved by the voters requires that nonstop journey to take no longer than 2.67 hours.

If Poole is right (and I haven’t reviewed his methodology or assumptions to know), will a 3+ hour ride between San Francisco and LA be a problem for attracting riders? It certainly doesn’t sound as compelling as 2 hours and 40 minutes required by the 2008 ballot initiative. And if you include door-to-door travel time, many riders could be looking at 5 hours between the two cities. That amount of time starts to look equivalent to flying, once you factor in travel to and from the airport, security, and waiting to board and de-plane.

So the only advantage over flying that high speed rail would have at that point would be a slightly cheaper fare, potentially nicer ride (smooth travel over land with great views), and the ability to access interim stops like Fresno or Bakersfield.

Of course, high speed rail has bigger concerns at this point than worrying about long-term travel times. The system’s leaders are struggling just to build the first truly usable section between Fresno and San Jose, and they have no money to get anywhere close to Los Angeles at this point.

But anything that we can do now to speed up the overall travel time will certainly yield ridership benefits down the, er, road.

A new national survey on attitudes regarding climate change shows some slight improvement in public acceptance of the science, as E&E News reports [pay-walled]:

The percentage of Americans who say they believe in global warming — 73 percent — reached a record high, according to the National Surveys on Energy and Environment (NSEE) (Greenwire, July 10). However, that percentage is only slightly higher than it was in 2008, when NSEE first conducted the survey. In 2010, acceptance of global warming had sharply dropped.

…

The survey also found that a greater proportion of Americans believe human activity is to blame for warming — at least in part. An even 60 percent of respondents said they believe humans are either mostly or partially responsible for rising temperatures. That’s 2 percentage points higher than the previous record found in 2008, 2009 and 2017.

Per usual, partisan, tribal identity determines willingness to accept the science, although even on that front Republicans are showing improvement:

The party divide is even greater when looking at the role that humans play in warming. A record 78 percent of Democrats believe that global warming is occurring at least in part because of human activity, compared to just 35 percent of Republicans.

It’s worth highlighting, the report points out, that fewer Republicans today say humans are causing global warming compared to a decade ago.

While public opinion is not where it needs to be to support the clean-tech mobilization required to combat climate change, it’s encouraging to see some improvement.

Baseball fans don’t like bad balls-and-strikes calls from home plate umpires. But rather than yelling at the ump, maybe they should look at their own tailpipe.

As UC Berkeley colleague Meredith Fowlie describes from a new study by James Archsmith (University of Maryland, College Park), Anthony Heyes (University of Ottawa), and Soodeh Saberian (University of Ottawa), bad air quality may be to blame for bad calls:

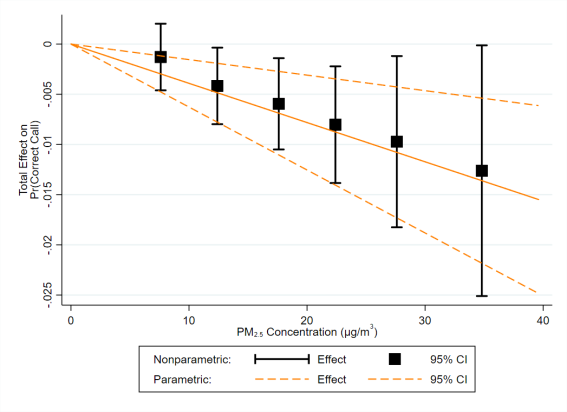

To sum up, these authors use publicly available data to estimate a causal relationship between air pollution exposure and umpire performance (measured as the share of umpire calls that agree with the computer-based assessment). After controlling for all sorts of factors that could affect an umpire’s judgement (such as venue, day-of-week, temperature, humidity, wind speed, pitch break angle, pitch type, etc.), they find a significant relationship between air pollution and on-the-job error rates:

People typically associate bad air quality with public health challenges, like increased respiratory ailments and premature death. But this study shows in stark terms how overall job performance decreases with increasing pollution.

And just look at the populations most likely to live in polluted areas, as the San Francisco Chronicle recently reported based on a new state study:

A new report released by the state Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment, a scientific arm of California’s Environmental Protection Agency, documents what environmental justice advocates have been saying for years — the racial makeup of communities suffering the worst environmental degradation in California are disproportionately Latino and African American.

…

Nearly 1 in every 3 Latinos and African Americans lives in the top 20 percent of most pollution-impacted communities. Only 1 in 14 whites calls these places home.

It’s one thing for these communities to face the historical disadvantages of discrimination and modern-day racism. But pollution as well presents an unjust and counter-productive barrier to achievement.

On that score, the State of California is striking out as much as home plate umpires at smoggy baseball games.