Kyle Hyatt at RoadShow on Cnet.com helpfully lists all the fully battery-electric vehicles available for sale right now in the United States, for anyone on the market or interested in the industry’s progress toward electrification. I condensed his alphabetical list below to focus mostly on mileage range per charge and price, as those are among the most critical features for many car buyers:

- Audi E-Tron: An electric SUV with a 95 kilowatt-hour battery, it provides a maximum range of 204 miles with a starting price around $75,000.

- BMW i3: A boxy urban EV with a carbon-fiber chassis to reduce weight, it has a relatively short range of up to 153 miles with a price at $44,450.

- Chevrolet Bolt EV: An alternative to the Tesla Model 3 (see below), this is vehicle has a solid range at 238 miles at a starting price of $36,620.

- Fiat 500e: Just under $33,000, you only get a range of 84 miles.

- Honda Clarity Electric: A range of just 89 miles, with only leasing options available.

- Hyundai Ioniq Electric: This hatchback sedan has 124-mile range and is listed for just over $30,000.

- Hyundai Kona Electric: An exciting new crossover SUV with a range of 258 miles and a price starting at $36,950.

- Jaguar I-Pace: An alternative to the Tesla Model X (see below), it has received excellent reviews on performance. It has a range of 234 miles and is priced around $70,000.

- Kia Niro EV: Another exciting new battery-electric SUV with a range of 239 miles for $38,500 to start.

- Kia Soul EV+: A range of only 111 miles for $34,000 starting price, with a recommendation to wait for the upcoming 2020 model.

- Nissan Leaf: The “granddaddy” of EVs, it has a decent range at 150 miles for under $30,000.

- Nissan Leaf Plus: Range at 226 miles for about $33,000.

- Smart Vision EQ Fortwo: Not a massive seller in the U.S. (I hadn’t even heard of this car before), and the 2019 model year will be the company’s last in the U.S. and Canada, given low sales numbers. The range is just 58 miles for about $30,000 (ouch).

- Tesla Model 3: The long-range all-wheel drive model offers a 310-mile range for around $50,000 or so. The elusive $35,000 version offers a range closer to 200 miles.

- Tesla Model S: The Model S 100D can now achieve 370 miles on a single charge at about $88,000 in price. The cheaper “75” version has range in the mid-200 miles.

- Tesla Model X: The X 100D now offers 325 miles of range on a single charge, with prices well over $100,000. A cheaper “75” version with less range is available.

- Volkswagen e-Golf: Range at 119 miles, with a starting price of $31,895.

Overall, it’s a solid list of electric vehicles with some relatively affordable options and diverse models available. And with automakers planning to roll out even more models in the coming few years, this list should grow dramatically from here on out.

As transit ridership falls nationwide, many system operators are struggling to redesign their bus networks to be more responsive to where people actually want to go and when. And now they can use those pocket-sized surveillance devices known as smart phones to assist them.

Adam Rogers in Wired reported on a data-fueled effort at LA Metro to track transit riders via their cell phone data:

Cambridge Systematics, a transportation consultancy, acquired the kind of location information your phone continuously produces—from every app you didn’t say “no” to. The data was “hashed” so that researchers could connect geolocations (at a resolution of about 300 meters) to a device but couldn’t link the device to a phone number or a number to a person. Even with the resolution blurred this way, you can still discern a picture.

They found that commute times are still true, with two peaks between 7 and 9am and another between 3 and 6pm. No big surprise there. But they also found a third peak, from mid-day to about 9pm, as people run errands and see friends. The trouble is that this third peak coincides with a time period when traditional transit slacks off.

Furthermore, people are traveling outside of areas with the greatest population density and at shorter distances, contrary to how long-distance commuter transit lines are designed. Specifically, the cell phone data showed that “only 16 percent of trips in LA County were longer than 10 miles. Two-thirds of all travel was less than five miles. Short hops, not long hauls, rule the roads.”

The agency surmises that faster, more frequent bus service on these specific, well-traveled routes could potentially net more riders:

[The] team ran billions of cell phone-registered trips through the agency’s regional planner to estimate how long they would take on the transit system. Then they ran the same trips through Google Maps to see how long they’d take to drive. Some 85 percent of trips could be taken on mass transit, but fewer than half were as fast as driving. … But laying the fare card data alongside the larger set of phone logs showed that even if a trip took about the same amount of time, just 13 percent of travel on that route was by transit.

Clearly a bus system redesign based on where people want to go and when, and relying on faster service, will be crucial for success. But speeding up the buses (and making them more appealing than passenger vehicle trips) will require a change in land use priorities. That means more bus-only lanes and less publicly mandated and subsidized parking for private vehicles. And it also means congestion pricing to reduce traffic and provide revenue for transit alternatives.

While privacy advocates may have concerns about the methodology used in this effort, at least LA Metro now finally has a more accurate window into traveler preferences across the region. But we’ll likely need larger political changes to fully address the problem.

Yesterday was a big day for SB 50 (Wiener), the bill to upzone residential areas near transit and jobs. The bill faced a potentially hostile Senate Governance and Finance Committee, chaired by State Senator Mike McGuire from Sonoma County and author of the rival Senate Bill 4. Despite the treacherous path, the outcome was a decisive win with only one vote against (Sen. Hertzberg of Los Angeles), albeit with significant amendments to the bill.

The new bill language has not been released, but based on the committee discussion and follow-up statements from Sen. Wiener and his office, the amendments essentially appear to do two big things (among other changes):

- Exempt SB 50 from counties with populations less than 600,000, except for cities within those counties with populations over 50,000 that have rail or ferry stops (see the green/purple parts of the flow chart below)

- Legalize “by right” permitting of single-family homes into duplexes, triplexes, and fourplexes across the state, albeit with only minimal demolition of existing structures allowed.

The amendments now make the overall bill relatively complex, but Berkeley-based artist Alfred Twu drew up this handy flow chart to explain how the bill will now work:

For a graphic on the counties now affected, here is a map from Barak Gila with the counties over 600,000 population (in which SB 50 applies) in yellow:

So did Marin County get a carve out, in a deal to merge the bill with county representative McGuire’s SB 4? Notable cities now apparently exempted from SB 50 include the SMART train and ferry stop in Larkspur and the ferry-stop towns of Sausalito and Tiburon. Yet San Rafael and Novato (two SMART train stops) are still covered by SB 50.

What about Sonoma County? Cities with SMART trains that no longer would be under SB 50 jurisdiction include Cotati, Rohnert Park, Cloverdale, Healdsburg, and Windsor. Still included are Petaluma and Santa Rosa.

In Southern California, Santa Barbara County’s Goleta and Carpinteria Amtrak stations also would not be covered by SB 50, while the City of Santa Barbara would still be affected.

Meanwhile, notable other cities with rail or ferry stops within those non-yellow counties, to which SB 50 will still apply, include Vallejo, Fairfield, Vacaville, Roseville, Rocklin, Madera, Modesto, Merced, Davis, Chico, Redding, and Salinas. And of course the remaining yellow counties represent major population and employment centers that could greatly increase housing production with SB 50 upzoning.

On balance, this new population criteria is not a bad compromise, as it means most of the core areas of California that prevent new housing are still affected. But the SMART train line is pretty well decimated by this compromise, as is the Santa Barbara Amtrak line. It’s a relatively small but painful price to pay, given the potential benefits statewide with the remaining areas.

Meanwhile, the fourplex by-right provision could potentially open up significant densification in California everywhere, a la the recent Minneapolis plan to end single-family zoning and allow triplexes city-wide. But could this new SB 50 provision encourage more high-density sprawl, with fourplexes in outlying areas that don’t have access to transit and therefore lead to more traffic and pollution? The original beauty of SB 50 (and its predecessor SB 827) was that it targeted transit neighborhoods to reduce overall driving miles. The fourplex provision could undermine those environmental benefits. Yet since the fourplexes (or other smaller divisions) can only involve minor demolition of existing structures (or building from the ground up on vacant parcels), the deployment may not be as sweeping as it might initially appear.

Overall, SB 50 cleared a major hurdle yesterday before its eventual advancement to the Senate floor, emerging relatively unscathed and with some potentially major new additions. If it passes that chamber, it will be on to the Assembly, with further carve-outs and compromises likely.

Climate advocates are pushing for “building electrification” to get new and existing building off of natural gas altogether through appliance-switching, which would provide significant greenhouse gas savings and indoor air quality benefits (as I discussed last week). Now we have a new study documenting some significant cost savings (as well as emission reductions) that this switch could provide to homeowners who get off natural gas.

Energy and Environmental Economics, Inc. (E3) released the study quantifying the economic impacts of this transition for consumers of various appliances in existing and new residential buildings. Funded by utilities including Southern California Edison, Sacramento Municipal Utility District, and the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, the researchers analyzed the cost impacts of electric air source heat pumps for space heating and cooling (HVAC), heat pump water heaters, electric and induction stoves, as well as electric and heat pump clothes dryers, compared individually to their natural gas alternatives.

The economic savings were notable. For new residential construction, all-electric appliances with today’s technology would result in lifecycle savings of $130 -$540 per year. It’s less clear though what the savings might be in general for retrofitting existing homes, as it depends on whether the building requires an electrical upgrade for all these new appliances and whether the homes have air conditioning.

The study also evaluated specific technologies in depth, including the key technology of electric heat pumps instead of using gas furnaces to heat homes. These heat pumps work by extracting heat from even cold winter air outside and pumping it indoors, and then pumping hot summer indoor air outside to cool a building.

E3 found the following cost-savings benefits with these heat pumps:

The installation of HVAC heat pumps can result in up to $550 per year in lifecycle savings relative to a combined gas furnace plus air conditioner(AC)system… However, homes without AC incur an extra lifecycle cost of $200 per year by switching to an HVAC heat pump. Heat pump water heaters (HPWHs) generate lifecycle savings of up to $150 per year over gas tankless water heaters in almost all home applications, but in retrofit homes, gas storage water heaters still appear to be the cheapest option… The net lifecycle costs of HPWHs are driven mainly by the capital cost.

Meanwhile, they found that electric hot water heaters generate savings of $150 per year over tankless natural gas heaters in new homes (not retrofits), as do electric cooktops. Electric clothes dryers though are currently more expensive than gas options.

In terms of emissions, the study found greenhouse gas reductions in single-family homes of 30%–60% over a natural-gas fueled home, given the projected electricity mix in 2020, and 80%–90% by 2050, assuming the projected carbon intensity of the grid by that year is realized.

Overall, the study is good news for those pushing for building electrification, as well as for any homeowner interested in making the switch to electric appliances to save money and reduce negative health impacts. With smart policy incentives to encourage adoption of these technologies in the home, from improved building standards to expanded financial incentives, California’s leaders could help homeowners achieve even further savings.

What’s the latest with California’s major proposed legislation to remove local restrictions on new housing near transit and jobs? I wrote back in December about Senate Bill 50 (Wiener), which would relax local requirements on density, parking, floor-area ratio and height (in some cases), for projects near transit and in high income “job-rich” communities that lack commensurate housing (read: Cupertino, home of Apple).

SB 50 also contains provisions to protect low-income renters from eviction from any new development under the bill and takes off the table (at least for the near future) large swaths of urban low-income areas deemed to be “sensitive communities.” For a visualization of what that means on the ground, see p. 11 (figure 5) of the CASA compact for a map of San Francisco Bay Area zones that would be exempted under this provision.

So how is the bill doing? Notably, SB 50 sailed through its first committee hearing last week with overwhelming approval. But it may face critical obstacles in its next hearing at the State Senate Governance and Finance Committee. That’s because that committee is chaired by State Senator Mike McGuire from Sonoma County, who authored a rival bill (Senate Bill 4) which would do much the same to relax local zoning near transit as SB 50, except with the big difference that it would exempt any “city with a population of 50,000 or greater that is located in a county with a population of less than 1,000,000” (which would exempt McGuire’s hometown of Healdsburg from the bill’s provision).

So the politics remain dicey going forward. The difference this year though is that Wiener has lined up powerful political support from organized labor, who like the job opportunities that would flow from more housing projects in urban areas. And by exempting in the near term “sensitive communities” with low-income tenants, Wiener has largely neutralized (for now) opposition from tenant groups who helped sink last year’s version, SB 827.

As a result, the opposition has so far been revealed as wealthy communities up and down California, who are resistant to allowing any new development or letting newcomers move in who can’t afford an expensive single-family home. They frequently use lines of attack like the bill is a “developer giveaway” or that proponents are “real estate shills.”

To counter these voices and win more support from advocates for low-income renters, Wiener has introduced amendments that tighten up the affordable housing requirements for any project that uses the bill’s provisions. Specifically, SB 50 now has ‘inclusionary zoning’ requirements in which developers with projects with between 20-200 units must make 15% of the units affordable to low-income residents (implemented on a sliding scale, with fewer units required if they’re available to extremely low-income residents), while 200-350-unit projects must provide 17% affordable units. Any project above 350 units must have 25% affordable units (also on a sliding scale depending on the income eligibility). Housing projects under 10 units are meanwhile exempt from providing any on-site affordable units, while projects of 10-20 units in size can pay in-lieu fees. With these provisions in place, the bill would likely lead to a significant deployment of subsidized affordable units to accompany new market-rate development.

But what practical effect will SB 50 likely have on the ground, assuming it can survive the messy politics and become law relatively intact? UC Berkeley’s Terner Center for Housing Innovation and Urban Displacement Project conducted an interesting case study policy brief and found that any likely boost to new housing under SB 50 would mostly be small scale and in high-income communities, though that impact varies depending on whether other local restrictions are in place.

The UC Berkeley study involved a parcel and financial feasibility analysis on four representative neighborhoods in the state, with the following highlights:

- Developers will get a much higher return on SB 50 projects in upscale areas, even with the higher land costs, meaning that most projects will be built in these areas and not in low-income areas (as I argued back during the SB 827 debates last year).

- Most of the available parcels (at least in these four study areas) are too small to support big projects, meaning most development will likely be of the 12-unit or less variety; in addition, the bill’s restrictions on developing properties with tenants will likely take a significant number of parcels off the table (a good thing, from the point of view of protecting current tenants from eviction).

- High on-site affordable housing requirements (discussed above) will be financially feasible in upscale areas but could sink projects in lower-income neighborhoods that otherwise barely pencil, so Sen. Wiener may want to consider a less rigid approach to the affordable housing requirements and instead scale them based on the value of the project.

- Remaining local government restrictions, such as high setback requirements and bans on projects that cast too much shadow (which was a dealbreaker for an important housing project in San Francisco that the board of supervisors just killed because it would cast occasional shadows at an adjacent park), will still impede projects, even if SB 50 passes.

- Developers may choose to ignore the benefits of SB 50 if a local government has already made it easy to permit projects at the current, locally determined height and density limits, just to avoid a protracted permitting fight that would come with using new, state-allowed higher limits.

The findings from this study should be clarifying for the SB 50 debate going forward. First, they show the relatively limited impact that SB 50 might have on the ground, at least compared to some of the hyperbolic rhetoric and initial studies about the predecessor bill’s impact in specific areas.

Second, SB 50 will likely end up being a just step (albeit a big one) in the right direction on boosting housing supply to match demand. Further reforms (some under consideration in other bills being debated this session) will need to focus on streamlining the permitting process for projects consistent with this new zoning. Otherwise, local governments are likely to respond to SB 50’s passage by adding more steps to the permitting process in order to kill projects through delay and multiple veto points. State legislation may also need to address the other zoning restrictions on new development that SB 50 leaves untouched, such as the aforementioned setback and shadow limits.

California’s current housing shortage certainly didn’t happen by accident — it’s the result of a complicated web of politics that SB 50 and its backers are trying to undo, piece by piece. We’ll have to stay tuned as more studies assess the bill’s impact and Wiener entertains more political compromises to win over support.

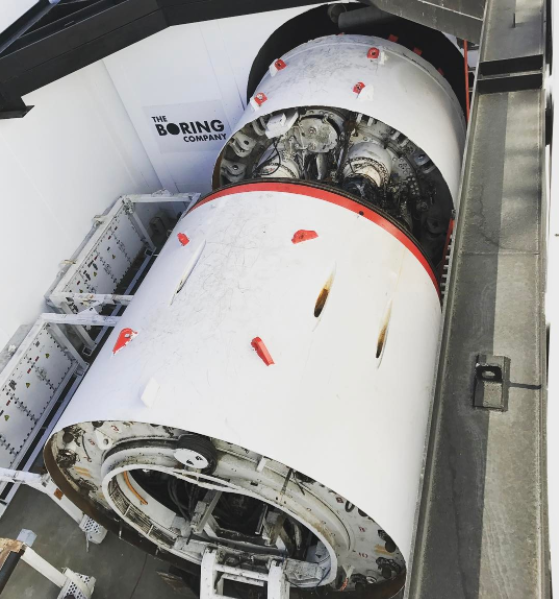

As I began researching the history of the Los Angeles Metro Rail system for my 2014 book Railtown, one particular aspect of the rail transit story shocked me. No, it wasn’t the petty political squabbles, short-sighted civic leadership, or selfish parochialism that slowed, weakened and sometimes stymied the development of a functional rail system in Los Angeles. It was the shocking price tag of building rail transit — particularly tunneling under busy city streets — and the absurd amount of time (decades in some cases) to dig tunnels that more than a century ago were done in a fraction of the time it takes today.

Like the rest of the United States, Los Angeles suffers from exorbitant costs and delays with tunneling. The 1.9 mile Regional Connector light rail tunnel under downtown, for example, will cost almost $1.7 billion and take at least 8 years to complete. Nationwide, as transit expert Alon Levy has documented, tunneling costs are out of whack even compared to other developed nations, with New York City’s $2.6 billion-per-mile Second Avenue subway as a particularly gruesome transit horror story.

So I was intrigued this past December when I learned that Elon Musk’s Boring Company was unveiling a demonstration tunnel in Hawthorne, California, that could be built quickly and at a fraction of the cost. How cheap? 1.14-mile for just $10 million, with potential long-term improvements in speed of up to 15 times over the current rate.

Many urbanists sneered, deriding the tunnel as nothing more than a sewer pipe and mocking the idea of a “tunnel for Teslas” as simply recreating the failed surface roadway patterns of the present — or worse, catering to the wealthy by allowing them to avoid the congestion caused by the plebeians above.

Many of these same urbanists already resented Musk for his work with Tesla, a company which promotes a vehicle technology that they rightly identify as destroying our urban fabric, while he also (ironically) works to remove one of the arguments against cars by eliminating their tailpipe pollution.

But what if Musk and his rocket scientists from SpaceX really could bring down the cost and time of tunneling? Imagine the transit projects that could ensue. I’ll offer four, just here in California alone:

- A subway under Wilshire Boulevard in Los Angeles, the densest corridor west of the Mississippi, while Metro, the public agency currently trying to build one, is mired in a decade-long, multi-billion dollar slog.

- A subway connecting West L.A. with Sherman Oaks and the San Fernando Valley underneath the dreaded Sepulveda Pass and the freeway parking lot known as “The 405.”

- A second Bay crossing connecting Oakland and San Francisco to address congestion on BART and possibly allow one-seat train service from San Francisco to Sacramento.

- A tunnel connecting San Francisco to Los Angeles and San Diego, completing the dream of the flailing high speed rail project.

Those four projects alone would make any California urbanist happy. Yet how seriously can we take the Boring Company’s claims regarding decreased tunneling costs and time?

I took a tour of the test tunnel in Hawthorne last month to try to gain more clarity on how the company is reducing tunnel costs. Three things stood out:

- The Dirt. Believe it or not, what to do with the dirt that comes out of tunnels is a big limiting factor. I heard this first-hand from the tunneling experts working on the Regional Connector project under downtown Los Angeles. Yet the Boring Company may have found something simple and innovative to do with that dirt: turn them into functional bricks. To prove their point, they built a Monty Python-style tower out of the bricks on site. If the bricks can be given away for free, it will greatly reduce costs. If they can sell the bricks for use in things like sound walls, they say they could actually make money on the tunnel (see the picture above and video below of the dirt brick-making process).

- Private funding incentives. The Boring Company is envisioning a privately funded network of tunnels throughout California and beyond. They are not necessarily contemplating bidding on large public sector contracts. As a result, the company appears to have incentives to cut costs in ways that some of the few big tunneling companies competing for select large public contracts may not. As an example, the company can save costs simply in terms of where they manufacture the tunnel’s concrete segments relative to the tunnel, a cost-saving step that they say the big tunneling contractors aren’t financially motivated to take.

- Lots of little things. There appears to be no one single leap forward with the Boring Company machine. But instead, the company’s leaders say they’ve managed a series of smaller innovations that combined together could help reduce the costs dramatically. Perhaps most significantly, the tunnel bore has a smaller diameter than many rail tunnels because they don’t need the wiring and infrastructure that a train needs, but it’s still large enough to fit a vehicle with the carrying capacity of a subway train. Their vision is to run battery-powered, autonomous vehicle platforms in the tunnels, rather than hard wire expensive rail cars. It’s a vision of where technology is heading that could eventually lead to existing rail transit being converted to autonomous, battery-powered, platooning shuttles, which could carry the same passengers as rail but for a fraction of the capital and operating costs.

In any event, we’ll soon see if these company claims are accurate, as the Boring Company appears ready to work on a tunnel under the Las Vegas convention center soon.

And while urbanists fret about the potential for expanded subterranean capacity for solo drivers, there’s no reason that the technology would only be employed for that use and couldn’t scale to the level of current public rail transit. The company sees Model X battery-powered platforms seating between 16 and 32 passengers traveling up to 165 miles per hour through LED-lit tunnels. And with five boring machines in action, they think they could reach San Francisco in just a year. That vision — though of private and not public transit — would only bolster urbanist goals of car-free living in more dense, transit-oriented communities.

A big limiting factor though, beyond the technology, may be permitting. Environmental review under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) may slow this deployment. Under the law, permitting agencies will have to study and mitigate environmental impacts ranging from paleontology to induced land use changes and traffic at the surface entry points to the tunnel. We’ll see how that process plays out, if the Boring Company starts moving forward on a project in California.

But if Musk and his crew have actually solved the technology and cost problem of tunneling, they will have given transit backers throughout the United States and beyond a big reason to celebrate. Because a revolution in tunneling is a pipe dream worth pursuing in our increasingly urban world.

Last year, Berkeley Law’s Center for Law, Energy & the Environment (CLEE) convened a symposium with a keynote address by Insurance Commissioner Dave Jones (now Director of CLEE’s Climate Risk Initiative), which featured insight and analysis of the role the insurance industry will play in a changing climate. CLEE is now releasing a symposium brief to present the key findings from the event, along with top recommendations for industry and policy makers. Download the symposium brief here.

The brief highlights key discussion points from the expert panels we convened on: climate science and insurance modeling; legal liability and climate change litigation; vulnerability of insurers’ assets and financial markets; innovative insurance products and proactive investments; and insurance affordability and availability.

Among the recommendations for state and industry leaders detailed in the symposium brief:

- Require insurers to employ increasingly detailed and comprehensive catastrophe models that accurately assess evolving wildfire and other risks while suggesting potential mitigation measures;

- Enhance disclosure of corporate and insurer risks due to climate change to increase transparency and decrease litigation risks;

- Develop carbon supply curves that map economic transition scenarios for specific market sectors;

- Offer innovative insurance products that can incentivize risk reduction, such as coverage upgrades for fire-hardened structures and discounts for green buildings; and

- Craft legislative reforms to ensure affordability and availability in all communities, like mandatory renewal offers for properties that meet mitigation and defensible-space requirements.

Many of the solutions discussed at the symposium (and in our comprehensive 2018 report Trial by Fire) have since been incorporated into law, including measures like SB 824 (Lara, 2018, limiting blanket policy cancellations following a major disaster event) and SB 30 (Lara, 2018, convening a working group to support ecosystem restoration-based insurance initiatives). As California experiences more concrete and consistent impacts of climate change, continued discussion of these solutions will become ever more essential.

CLEE will host a free webinar this morning at 10am (Wednesday, March 27th) to discuss the new symposium brief and officially welcome Dave Jones to CLEE. Please join us to hear his perspective on the issues covered in the brief, as well as the broader role of the insurance and financial sectors in a changing climate.

The Two Hundred is a new industry-backed group with a familiar refrain: California’s housing shortage (and overall low level of affordability) is caused by out-of-control environmental laws. The group is now suing the State of California for pursuing “racist” climate policies that they claim primarily displace people of color by driving up basic living expenses.

They have a website, some prominent civil rights advocates that have joined them, and a professional video to make the case that California’s housing production is stymied solely due to environmental review under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). Specifically, they allege that the need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions under the state’s climate “scoping plan” is exacerbating environmental review by saddling new housing projects with requirements to reduce on-site energy usage and vehicles miles traveled. (They also blame high electricity costs for making the state unaffordable, as a result of mandates to procure more renewables and reduce on-site energy usage, even though these policies are enacted under separate statutes from the state’s climate law.)

Does this lawsuit have merit? No, but the group has correctly identified a major problem in California: the state is unaffordable for too many residents, almost exclusively due to high housing costs resulting from a decades-long history of under-building homes relative to job and population growth.

But the problem with their lawsuit is that they are blaming the wrong policies and decision-makers. Instead of starting by identifying what actions most constrain housing growth and affordability in the state, and then asking how the state is addressing or exacerbating these barriers, the lawsuit assumes (without evidence) that CEQA is the prime barrier to housing.

But study after study has debunked the idea that CEQA lawsuits are a major factor impeding new housing. Instead, the real culprit is restrictive local zoning and burdensome permitting processes.

So why isn’t the group suing every NIMBY-captured local government in the state for preventing housing, which drives up costs and forces long commutes? First, they probably don’t have a great legal cause of action against all these cities — or a convenient way to sue hundreds of them — whereas they can go after a state agency like the California Air Resources Board (CARB) more easily in court. Second, given their industry-backed leadership, I suspect that they don’t really care about local barriers to housing. Instead, they are exercising a longstanding beef against CEQA for its role in slowing megaprojects, especially sprawl development.

Yet the lawsuit is worth keeping an eye on, given the savvy of the industry lawyers behind it and the underlying truth of the problem they’ve identified, if not the remedy to address it.

For more information, you can watch their full anti-CEQA video here, complete with multiple Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. references:

For those in the Bay Area, Berkeley Law’s Center for Law, Energy and the Environment (CLEE) will be hosting a free brown bag lunch talk today with Prof. Michael Grubb, professor of Energy and Climate Change at the University College of London.

Professor Grubb has been at the forefront of the United Kingdom’s successful-to-date effort to reduce carbon emissions from its electricity sector. In a talk entitled “Innovation, economics and policy in the energy revolution: Insights from the UK electricity transition and wider implications,” Dr. Grubb will describe how this transition occurred.

The event will run from 12:50 to 2pm in Boalt Room 10. More info and RSVP here. Hope to see you there!