California has a paradoxical history with its environment. On one hand, the state boasts incredible natural beauty, along with a government that is an internationally recognized leader for strong environmental policies. But the state’s residents have also caused severe environmental destruction, particularly in the late nineteenth century — some of which helped spur the mobilization that led to these environmental successes.

Looking at California’s history, what were some of the most striking examples of environmental destruction? To qualify for this “Top 10” list, the destruction had to be irreparable (at least in anyone’s lifetime) and of a uniquely beautiful environmental feature (landscapes and plants). Of note, animals are not included, nor is an assessment of the economic trade-offs or alternatives.

10. Quarrying Morro Rock

Morro Rock is California’s Gibraltar, a striking coastal feature just north of San Luis Obispo on Morro Bay. It’s a remnant, exposed rocky volcano, visible from miles away. The local Chumash tribe consider it a sacred site (named Lisamu) and have special access to the top for religious ceremonies. But half of the side of the rock was quarried from 1889 to 1969 to form the bay breakwater, leaving a massive scar.

9. Draining the Owens Valley and Mono Lake

The Owens Valley is a remarkable north-south valley created by fault separation along the eastern Sierra Nevada mountains. Just past the northern end of the valley lies Mono Lake, an ancient salt-water body of water. In the early 1900s, Los Angeles city leaders surreptitiously purchased land and water rights to direct the Owens river, and eventually the streams supplying Mono Lake, into aqueducts to service Los Angeles real estate development. The result was a shrunken Mono Lake and desiccated Owens river valley and lakebed, creating toxic duststorms and economic and environmental blight in the region.

8. Channelizing the Sacramento-San Joaquin Bay Delta

The Delta sits between California’s Central Valley and San Francisco Bay, draining most of the water from the interior of the state to the Pacific Ocean. It is one of the largest estuaries in western North America, once featuring a vibrant ecosystem with rich soil. Chinese laborers were employed to build levees between the 1850s and 1870s to dam and farm the land. Today, these levees are at constant risk of collapse, jeopardizing much of the state’s water transfer system from north to south, while much of the Delta ecosystem is in a state of freefall.

7. Clear-Cutting the Sierra and Lake Tahoe Pine Forests

The Sierra Nevada mountains used to be blanketed in old growth pine forests, which included trees the size and age of giant sequoias in some cases. But in the mid- to late-nineteenth century, much of the mountains, including the entire Lake Tahoe basin, was clear cut largely to build underground silver mines in neighboring Nevada. Today, the resulting second-growth forests of clumped juvenile firs and pines creates a fire-prone jumble that forest officials are struggling to manage properly. You can still see the original old-growth pines only in places like DL Bliss State Park along Lake Tahoe, ironically preserved by one of the industrialists who profited from the logging in the first place.

6. The Los Angeles Freeway Embrace

The City of Los Angeles is ringed by semi-arid mountains, distant snow-capped peaks and a long coastline featuring wetlands, coastal bluffs and sandy beaches. Yet in the middle of the twentieth century, city and state leaders enabled the paving of much of this landscape via the construction of multiple large freeways, starting with the Arroyo Seco Parkway in Pasadena, the first freeway in the country. This automobile network induced significant traffic congestion and sprawling development that to this day generates a substantial amount of air pollution, despite efforts to retrofit the city back to a Railtown.

5. Damming Hetch Hetchy Valley

Hetch Hetchy is a rare glacial-carved valley within Yosemite National Park in the Sierra Nevada, featuring a meandering Tuolumne River and similar in scale and beauty to the more-famous Yosemite Valley to the south. San Francisco water engineers at the turn of the last century sought to dam this bathtub-shaped valley to bring mountain water to the groundwater-challenged San Francisco peninsula. Over the objections of John Muir and the Sierra Club, the federal government and San Francisco officials approved the dam, flooding and permanently marring this geologic wonder.

4. Logging Giant Sequoias

Giant sequoia trees can live up to three thousand years and grow to become the largest living things on Earth. California’s western Sierra Nevada mountains host the last remaining 77 groves on Earth. In the late 1800s, Californians chopped down about one-third of them. Worse, most of the wood from the trees would shatter on impact with the ground, so these residents could only use the wood for building fences or manufacturing shingles.

3. Wetlands Destruction

California once boasted over 4 million acres of wetlands, out of 163 million in the state, from coastal lagoons to Central Valley floodplains. These lands featured abundant bird and aquatic life, among other features. But 90 percent of them were destroyed by river damming and channelization. Today, what remains hosts 55% of the state’s endangered species, with much of those lands now irreparably lost to farms, cities and sprawl.

2. Clear-Cutting Old-Growth Coastal Redwoods

Coastal redwood trees grow to be the tallest living things on Earth and can live up to two thousand years. They are located along California’s coast up to the Oregon border. But starting in the mid-nineteenth century through the 1980s, loggers cleared 95% of the original old growth forests. Once cut, new trees may quickly grow up in a ring around the old stump but resemble toothpicks compared to the originals. To view what was lost, you can visit Muir Woods 12 miles from San Francisco, Big Basin Redwoods State Park near Santa Cruz, or Redwood National Park near the Oregon border.

1.Hydraulic gold mining

In the mid-1800s, mining companies discovered that they could harvest gold from the Sierra Nevada foothills more easily if they blasted the rock with high-pressure water. In a few short years, these companies denuded and deformed much of the Sierra foothills, sending debris into the Central Valley and mercury pollution into the San Francisco Bay, where it still sits today. A federal judge stopped this type of mining in the 1884 decision Woodruff v. North Bloomfield Gravel Mining Company, in order to protect agricultural land in the Central Valley. But much damage was permanently done to the foothills, agricultural areas of the Central Valley and San Francisco Bay water quality.

____________________________________________________________________________

There are potentially many other examples of harmful environmental decision making to choose from, which you can suggest in the comments. The one upside of many of these tragedies is that they resulted in a public backlash that inspired long-lasting environmental reform and organizations, with compounding successes to this day. Much of the destruction described here could have been far more significant without this citizen (and often business) mobilization. But still, what is lost is forevermore, a cautionary tale that should give us pause before we sacrifice any more of California’s environmental heritage.

The COVID-19 virus and global response has sparked massive changes in our economy and every day lives. There is a lot conjecture about how this experience may shape long-term responses to climate change, from a crashing oil and gas market to the potential for the public taking scientific projections of calamity more seriously.

I’m mostly pessimistic about how the virus and our response to it will shape long-term climate change efforts. My guess is that life will mostly return to our normal fossil fuel-burning ways once the pandemic eases. And in the short term, the economic recession will undermine clean tech investment, while virus panic will hurt transit ridership and possibly undercut support for urban living.

But there’s one potential bright spot for the climate that may outlive this current era: working from home. Prior to the pandemic, only 4% of U.S. employees worked from home, according to Global Workplace Analytics. But now more than half of the 135-million people in the U.S. workforce is setting up in a home office.

The firm estimates that at this rate, by the end of next year 25% to 30% of the total U.S. workforce will be telecommuting, the carbon equivalent of “taking all of New York’s workforce permanently off the road,” per Kate Lister, president of the firm.

From a greenhouse gas perspective, it means many fewer driving miles from commuting. Otherwise, approximately 86% of Americans drive to work, according the National Household Travel Survey. If just 25% of Americans began teleworking even one day per week after the pandemic, total vehicle miles traveled would fall by 1%, which is actually a significant amount of the more than 3.2 trillion miles driven in the U.S. in 2018. The numbers could go much higher if telecommuting were multiple days per week for more people.

And why might these work from home habits stick, as opposed to other environmental friendly measures taken during the pandemic? Simple: working from home is more convenient and productive for most people. But prior to the pandemic, many managers weren’t comfortable allowing the practice, believing (falsely) that it would hurt bottom lines.

But now that everyone who can work from home is forced into this arrangement without calamity, my guess is that this manager resistance will fade. And any employees who might have guessed they wouldn’t enjoy working from home may also be finding that there are significant upsides, which would lead them to agitate for supervisor permission to continue the practice.

Telecommuting by itself won’t solve transportation emissions, but it could set the stage for further reforms, such as dedicating more public spaces like streets for pedestrians and bicyclists, as European cities are now contemplating. After all, people working at home will want to take walks and get out for exercise, and in cities that means streets will need to be converted.

In addition, telecommuting may solidify the current practice of transitioning work travel and conferences to on-line events and meetings. If people are already comfortable working at home, they may be more likely to continue participating in panels and meetings remotely, too, which will reduce car and plane flights.

Perhaps there will be other long-term climate benefits from COVID-19. But to my mind, working from home seems like the most obvious candidate for a pandemic culture-changer that reduces emissions.

California is the seventh-largest oil producing state in the country, with a fossil fuel industry that is responsible for billions of dollars in state and local revenue and other economic activity each year. Yet continued oil and gas production contrasts with the state’s aggressive climate mitigation policies, while creating significant air and water pollution, particularly for disadvantaged communities in areas where much of the state’s drilling occurs.

As a result of these risks, many advocates and policymakers seek ways to enhance regulation of and eventually phase out oil and gas production in California. Recent global price wars and declining demand from the COVID-19 pandemic have underscored the need to conduct this phase-out in a just and orderly fashion.

To provide legal options for policy makers to facilitate this transition, Berkeley Law’s Center for Law, Energy and the Environment (CLEE) is today releasing the new report “Legal Grounds: Law and Policy Options to Facilitate a Phase-Out of Fossil Fuel Production in California,” co-authored with CLEE climate law and policy fellow Ted Lamm.

The report analyzes steps California leaders could pursue on state- and privately-owned lands to achieve this reduction. Among the options discussed, state leaders could:

- Enhance regulatory authority over drilling by clarifying the need for the California Geologic Energy Management Division (the state’s primary oil and gas regulator) to prioritize environmental and climate impacts over production;

- Heighten scrutiny on permitting via comprehensive environmental review with mandatory, site-specific mitigation measures under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA);

- Institute minimum statewide drilling setbacks of at least 2,500 feet or more from sensitive sites, such as schools, parks, and houses;

- Implement a per-barrel or per-well severance tax and dedicate the revenue to projects that further the goal of transitioning away from fossil fuel; and

- Task the California Air Resources Board with devising and implementing a comprehensive plan for a phase-out of all in-state oil and gas production by a date that tracks with overall climate goals.

To learn more about the report findings, please join our free webinar on Tuesday, May 12th, from 11am to noon, with Sean Hecht of UCLA Law and Ingrid Brostrom of the Center on Race, Poverty & the Environment. Registration is here.

This report ultimately comes at a unique moment in the history of in-state oil and gas production. The industry is struggling economically due to a global collapse in oil prices and a decrease in demand from COVID-19-related shutdowns. As sheltering Americans temporarily buy less gas and many drilling companies are approaching or entering bankruptcy with record-low oil prices, an intelligently structured phase-out could result in less harm to jobs and local economies. And California’s actions could demonstrate to other states and countries how to successfully sunset their fossil fuel production.

We hope the menu of law and policy options presented in Legal Grounds will assist state leaders in addressing these challenges and charting a new course for California’s in-state fossil fuel production.

The global transition from fossil fuel-powered vehicles to electric vehicles (EVs) will require the production of hundreds of millions of batteries. The need for such a massive deployment raises questions from the general public and critics alike about the sustainability of the battery supply chain, from mining impacts to vehicle carbon emissions.

Growing demand for the mineral inputs for battery production can provide an opportunity for mineral-rich countries to generate fiscal revenues and other economic opportunities. But where extraction takes place in countries with weak governance, the benefits expected by citizens and leaders may not materialize; in some cases extraction might even exacerbate corruption, human rights abuses and environmental risks.

Many EV proponents and suppliers are aware that supply chain governance problems pose a challenge to the evolution of the EV industry, but outstanding questions remain about how these challenges materialize. To address some of these questions as part of a broader research initiative, UC Berkeley School of Law’s Center for Law, Energy & the Environment (CLEE) and the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI) are today releasing the new brief “Building a Sustainable Electric Vehicle Battery Supply Chain: Frequently Asked Questions.” It provides basic information on the EV battery supply chain and key battery minerals, such as cobalt and lithium, and addresses the following questions:

- What does the supply chain for EV batteries comprise?

- How do carbon emissions from EVs compare to traditional internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles?

- What are the most significant challenges in managing the mineral extraction necessary for the EV supply chain, and what sustainability and human rights initiatives apply?

Based on existing research and consultation with experts throughout the EV battery ecosystem, the FAQ presents a diagram of the steps in the supply chain and data on the largest producers of key battery mineral. It offers the following key findings:

- EVs offer significant life-cycle greenhouse gas savings over internal combustion engines, with estimates up to 72-85 percent in areas with high renewable energy penetration.

- While the EV battery supply chain involves a range of actors across the globe, the limited number of players at key intermediate manufacturing stages has the potential to create “bottlenecks” that complicate efforts to promote sustainability.

- In terms of the long-term availability of minerals needed to meet projected global EV demand, expert opinions differ. Governance decisions and the relationships between mineral-producing countries and commercial players will have a major impact on the pace of supply growth, while efforts at technological innovation in battery chemistry and recycling could decrease the need for additional mining.

- Human rights impacts from EV battery mining are particularly significant for cobalt, as a result of governance challenges in the Democratic Republic of Congo that have allowed corruption and economic inequalities to persist.

- Local environmental impacts from EV battery mining can be acute in some contexts but also reflect broader challenges and impacts from mining in general, particularly when compared to the environmental damage from baseline oil and gas production.

- The EV battery and mining industry features a lengthy and diverse set of standards and initiatives designed to improve sustainability, yet improved transparency and compliance still require enhanced coordination among stakeholders.

This FAQ is the first report in a stakeholder-led research initiative by CLEE and NRGI that aims at greater sustainability in the EV battery supply chain. A full policy report coming later in 2020 will identify high-priority actions that private and public sector players can take to ensure a sustainable EV battery supply chain. While the EV battery supply chain entails a range of sustainability-related risks—as do most mineral extraction and production supply chains—participants can take collaborative steps to manage it effectively and in the public interest. Such approaches will reduce harms while helping the world meet long-term climate goals.

This post was co-authored with Ted Lamm (CLEE climate fellow) and Patrick Heller (advisor at the Natural Resource Governance Institute and a senior visiting fellow at CLEE)

Legendary singer-songwriter Bill Withers passed away this week of heart complications. He was 81. His creative peak came in the 1970s, when he wrote and sang a string of memorable, rock-soul hits such as “Lean On Me,” “Just The Two of Us,” “Use Me,” and “Lovely Day.”

The 2009 documentary “Still Bill” captured much of his musical essence, including his upbringing in a West Virginia coal town and early career as an airplane mechanic before becoming a musical phenomenon:

And here is Bill singing one of my favorites, Grandma’s Hands:

Rest in peace, Mr. Withers, and thanks for the great music.

With the COVID-19 virus shutting down cities and countries all over the world, anti-urban advocates are seizing the moment to argue that pandemics prove density is bad. For example, longtime sprawl booster Joel Kotkin argues that shelter-in-place orders and fear of contagion will push people to demand more lower-density homes, far from crowded and ailing cities.

These advocates have some support from scientists. Some public health experts point to density as a factor in spreading the disease, as the New York Times recently reported:

“Density is really an enemy in a situation like this,” said Dr. Steven Goodman, an epidemiologist at Stanford University. “With large population centers, where people are interacting with more people all the time, that’s where it’s going to spread the fastest.”

But at the same time, some of the densest nations around the world have had the most success fighting the spread of the virus, such as Taiwan, Japan, Korea, and Singapore. In particular, Taipei and Saigon city leaders (among others) have been extremely effective in controlling the contagion.

By contrast, low-density suburbs have been among the first sites where the virus took hold in the U.S., such as in Kirkland, Washington, and New Rochelle, New York. Similarly, the outbreak in Italy began in small towns outside of Milan.

Given this evidence to date, governance appears to be far more important a factor than density in limiting the spread of the virus. Furthermore, density could actually be more helpful in controlling the spread, as governments can more easily enforce sheltering in place in smaller zones, while emergency response times and trips to the hospitals are typically faster than in far-flung rural areas (which also suffer a dearth of available medical facilities, as my colleague Dan Farber pointed out).

But the question remains: could the pandemic dampen demand for housing in dense urban environments, regardless of the science? People may still (perhaps irrationally) fear a dense environment as a disease-spreader. Or they may emerge scarred from this era of “sheltering in place” and prefer larger homes with outdoor space, just in case another pandemic requires a new round of society-wide house arrest.

History may provide some guide in answering this question, as low-density homes in the 1920s were certainly sold to the public as antidotes to disease-ridden, crowded cities. As Emily Badger noted in the New York Times, “[r]espiratory diseases in the early 20th century encouraged city dwellers to prize light and air, and something that looked more like country living.”

But as policy makers weigh options to boost density, they should keep in mind the myriad public health benefits that density can provide. It can foster more physical fitness from increased walking and biking instead of sedentary, automobile-based sprawl; mental health benefits from strong and frequent community interactions; and stronger health care from pooling resources for big public hospitals.

Furthermore, in an era of climate change, living in more compact environments can guard against extreme weather events. In California, for example, urban neighborhoods are among the most fire-safe during destructive and worsening wildfires, while also largely avoiding the electricity shut-offs needed to avoid igniting fires in high-fire sprawl zones. From a public safety perspective, density can now save lives during wildfires.

And sheltering in place in a more compact environment can bring elements of joy and community during a time that can otherwise feature crushing physical and emotional isolation. Witness scenes of a balcony opera performance in Florence to help neighbors cope with the lockdown or police in Mallorca, Spain singing songs for neighbors while enforcing the quarantine.

The human connection found in dense neighborhoods can not only help us get through this particular challenging time in human history, it can build the foundations for a healthier, more sustainable future. The current pandemic won’t change that reality.

Sen. Scott Wiener is back trying to boost California housing production again, after his SB 50 legislation to upzone for apartments around transit died in the State Senate in January. This time, he’s proposing a “lighter touch” approach, salvaging an SB 50 provision that would end single-family zoning across the state.

Senate Bill 902 would authorize minimum residential zoning of duplexes in unincorporated county areas or cities under 10,000 residents. Triplexes would be the minimum density for cities between 10,000 and 50,000 residents, while fourplexes would be allowed for cities of 50,000 or more.

Furthermore, while local standards on height, setbacks, and fees, etc. would remain in place, any approval for these multiplexes would be “by right,” meaning environmental review would not apply under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) and permits would not be discretionary. In addition, the bill would not apply to parcels with renters any time in the last seven years, historic structures, or high-fire zones.

But wait, there’s more — and this time with a more explicit transit and environmental hook.

SB 902 would also allow local governments the option of rezoning any parcel (including for commercial uses) for up to 10 units in density, provided the parcel is located in a “transit-rich area, a jobs-rich area, or an urban infill site.” The definition of transit-rich means within one-half mile of any rail station or major bus stop, and urban infill site essentially means a previously developed spot surrounded by existing uses on at least 3 or 4 sides. “Jobs-rich” would need to be defined by the state’s planning and housing agencies. Like the multiplex provision, all permitting for these 10-unit parcels would be by-right and therefore not subject to CEQA.

This 10-unit opt-in provision holds the most promise to boost transit ridership and reduce vehicle miles traveled (aka “traffic”), the reason the state is now falling behind on transportation emissions. By allowing an opt-in for greater density, SB 902 provides off-the-shelf tools for local governments that actually want to see more housing near transit and jobs.

That said, the problem in California is that too many transit-rich, high-income local communities want nothing to do with more density. So many of the most critical transit-rich communities (San Francisco Bay Area suburbs and Westside Los Angeles cities like Beverly Hills) likely won’t budge on this tool. Their property-rich residents are just fine with their neighborhoods as they are.

The upside for the environment on the multiplex provision is that accommodating more residents in existing residential neighborhoods could also boost transit, if those new multiplexes are near rail stations and bus stops. And if those new residents drive, at least they would presumably have a shorter commute than if they lived in new exurban sprawl communities (the primary affordable housing alternative, short of leaving the state altogether).

The potential downside is that many of these multiplexes might be in far-flung subdivisions, meaning the new residents will have longer commutes than if SB 50 had passed and they could have lived in an apartment near transit. But the SB 50 opportunity, and all the mandatory affordable housing that would have come with it, is now passed.

As for the politics on SB 902, it seems likely it will be similar to SB 50. Wealthy suburbanites that sank SB 50 will be back en masse to oppose SB 902. Labor may not like the by-right provision (they use CEQA to force project labor agreements on developers) but may appreciate the construction jobs.

The political wildcard will be equity and affordable housing groups, which helped sink SB 50. Will they care about suburban upzoning? Some of these affected areas will have low-income tenants. While as mentioned the bill doesn’t allow redevelopment with renters present anytime in the last seven years, many tenant advocates may not care. Some are even hostile to market-rate development of any type, hoping instead for a government takeover of housing production. So it will be critical to see what positions they take on SB 902, as their opposition to SB 50 provided important political cover for wealthy opponents.

In addition, will environmental groups step up to support the measure? Most were MIA on SB 50, with the exception of NRDC, ClimateResolve and a few others. Some were even opposed, cowed by the tenant group opposition or beholden to NIMBY constituents. So SB 902 gives them a fresh opportunity to finally develop a coherent position on this most pressing environmental issue.

Ultimately, if Sen. Wiener can at least limit tenant group opposition, along with the wealthy NIMBYs who may be more scandalized by the prospect of an apartment building than a triplex, he may have a chance to get the bill passed. And ultimately, it will require the governor, who campaigned on 3.5 million new housing units but has instead seen backwards progress, to step up and get more involved in the political process.

Either way, if the bill has legs, we’ll likely see many changes as it winds its way through the process of political compromise. I’ll be following them closely.

The San Francisco Bay Area’s population and job centers are famously divided by the bay itself, with jobs and housing on the San Francisco side accessed by commuters to the east via the Bay Bridge or the transbay BART tube. The dream for unlocking access via more transit — and possibly high speed rail — depends on building a second tube

ABC 7 News covered the most recent plans for a potential project, featuring a short clip of me:

This is a subject we covered on my very first City Visions show as a host back in 2016. Regardless of what shape it takes, one thing we know for sure is a second transbay tube will take longer and probably cost more to build than the current plans will estimate. But such a project will be critical for long-term sustainable mobility in the region.

Tonight on City Visions at 7pm, we’ll discuss the new Prop. 13, a $15 billion bond measure on the March ballot in California, which could change the landscape for public education funding.

In the 1970s, California ranked 7th out of all states in per pupil funding. Now it’s 41st in the nation, according to Governor Gavin Newsom. The education budget line is robust, but most Californians think it is not enough. How does the state pay for public education, K through college? In addition to the new Prop 13 on the ballot, what about efforts to reform the old Prop 13, which restricted property taxes that were used to pay for schools?

To discuss these issues, we’ll be joined by:

- Ricardo Cano, Education Reporter, Cal Matters;

- Ted Lempert, President, Children Now and former founding CEO of EdVoice; and

- Sean Walsh, Principal, Wilson Walsh George Ross Consulting.

Tune in and ask your questions at 866-798-TALK! We’ll be streaming live at 7pm and you can access on 91.7 FM KALW in San Francisco.

The California State Senate this morning (for a second time after an initial vote last night) narrowly and finally killed SB 50, a major climate-land use bill that would have allowed apartment buildings near major transit stops and job centers. Despite high-profile opposition from some low-income tenants groups, the senators voting against the bill largely represent affluent suburbs.

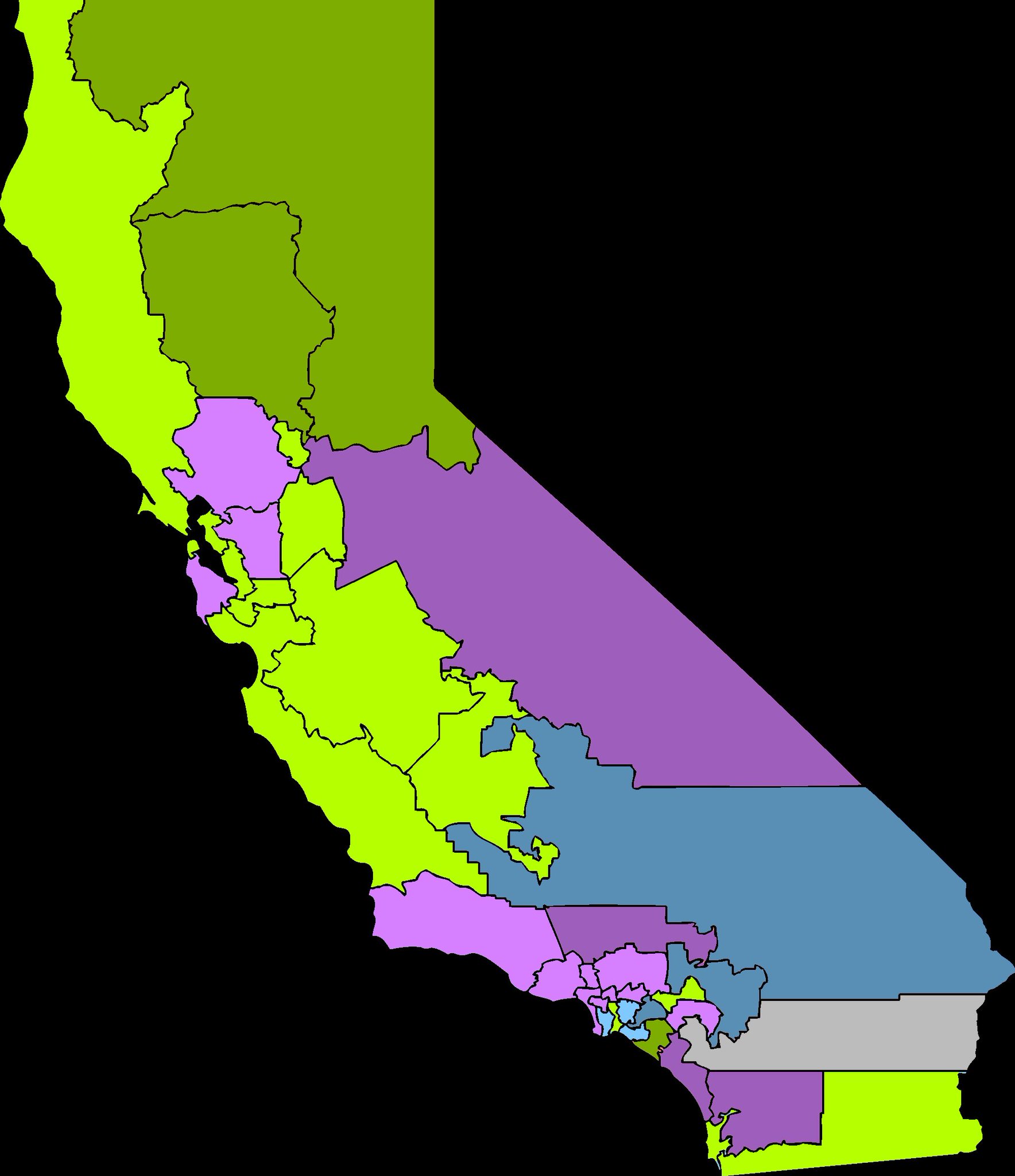

To illustrate the geographical divide, a Twitter user put together this map of the senate districts and votes, with purple opposed, green in support (light for Democrat and dark for Republican), and blue abstaining:

As you can see, the “opposed” senators largely cluster along on the affluent coastal and suburban areas. This dynamic is particularly apparent in the San Francisco Bay Area, where representatives of the urban core supported the bill (including bill author Sen. Scott Wiener and Sen. Nancy Skinner). But the senators representing the suburban, high-income Silicon Valley communities (Sen. Jerry Hill), affluent East Bay suburbs (Sen. Steve Glazer), and the Napa area (Sen. Bill Dodd) were all opposed.

Meanwhile, Southern California Democrats representing high-income coastal suburbs were almost uniformly opposed:

- Sen. Hannah-Beth Jackson, representing Santa Barbara communities;

- Sen. Henry Stern, representing Malibu and suburbs north of urban Los Angeles;

- Sen. Ben Allen, representing the Westside of Los Angeles, including Manhattan Beach and Beverly Hills;

- Sen. Anthony Portantino, representing La Cañada Flintridge and who had unilaterally shelved the bill last year in his committee; and

- Sen. Bob Hertzberg, representing the San Fernando Valley.

Notably, there were some standout “profiles in courage” votes in favor of the bill, including:

- Sen. Lena Gonzalez from Long Beach, despite opposition from city leaders in her district;

- Sen. Brian Dahle from the conservative, northern inland part of the state, who recognized the damage sprawl does to farmland;

- Sen. Bill Monning of Carmel who spoke passionately about the inequality and devastating commutes wrought by exclusive local land use policies; and

- Sen. John Moorlach of coastal Orange County, a Republican (and bill co-author) who appreciated the legislation giving more property rights to landowners.

What were the argument of opponents? They largely involved these issues:

“The bill will not produce enough affordable housing.” The bill in fact contained minimum requirements that projects receiving benefits under the bill include affordable units. As a result, SB 50-type reform would result in the biggest boost to subsidized affordable units in the state’s history, at possibly a seven-fold increase.

“SB 50 takes away local control.” To the contrary, the bill would give low-income communities five years to develop local plans for infill housing and two years for other communities to plan to meet these standards. Locals would be free to set more aggressive standards on affordability and relax restrictions even more if they wanted to do so. SB 50 also did not alter local permit approval processes. Furthermore, for senators who profess to care about the housing shortage, local control is the single biggest cause of the shortage, particularly through restrictive zoning.

“The bill will lead to gentrification and displacement.” This is a real, yet overstated, concern that the bill addressed with numerous provisions to protect against new developments displacing low-income tenants (a massive, ongoing problem that predates SB 50 and is made worse by the exclusionary housing policies SB 50 was designed to prevent). Furthermore, local governments were free to go beyond those protections. Second, as UC Berkeley’s Terner Center for Housing Innovation documented, any projects under the bill only “pencil” in high-income areas where developers get higher returns. Finally, as the Urban Displacement Project at UC Berkeley (in collaboration with researchers at UCLA and Portland State) found, new market-rate and affordable housing at a regional scale reduces gentrification and displacement overall.

Finally, Sen. Henry Stern uniquely argued against the bill for encouraging development in high-fire zones. It was an odd argument, considering that the SB 50 zones around transit are in some of the only non-fire, urban zones in the state, while the bill contained explicit language preventing application in high-severity zones. Furthermore, encouraging growth in infill areas reduces pressure to sprawl into the same wildlands Sen. Stern is worried about. Yet Sen. Stern was convinced that the protections weren’t strong enough and conceivably was worried that the provision in the bill allowing conversion of single-family homes into fourplexes would put more people into harms way. Given this logic, will Sen. Stern now support a bill banning new construction in high-fire zones? Or would he have supported the bill with an amendment banning such construction? He did not respond to these questions on his Facebook page.

So what’s next? The bill or some form of it could be brought back this legislative session as a “gut-and-amend” of an existing bill. Indeed, Senate pro tem Toni Atkins vowed shortly after the vote to bring a housing production bill back before the legislature this session. Supporters could also try a more limited approach, such as exempting controversial parts of the state from the bill.

Otherwise, given the long-term problem and entrenched opposition to change, the fact that such a landmark bill only fell three votes short is quite an accomplishment. Since the problem will only get worse, the political pressure to act will increase. That means that something like SB 50 will ultimately pass in California. It will be too late for those priced out in the near term, and possibly too late to address our 2030 climate goals, which will require reduced driving miles from housing closer to jobs and transit absent major technological innovation. But it will happen, because reforming our land use governance is the only way to solve this problem.